O'Hare International Airport

| O'Hare International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City of Chicago | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Chicago Department of Aviation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Chicago | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | February 1944[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 668 ft / 204 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 41°58′43″N 87°54′17″W / 41.97861°N 87.90472°WCoordinates: 41°58′43″N 87°54′17″W / 41.97861°N 87.90472°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website |

www | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

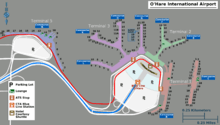

| Map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

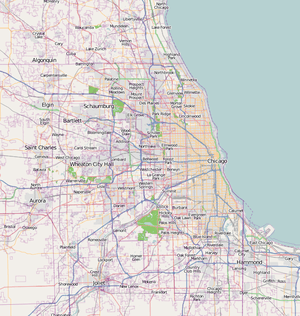

ORD Location of airport in Chicago  ORD ORD (Illinois)  ORD ORD (the US)  ORD ORD (North America) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Helipads | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2017) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

O'Hare International Airport (IATA: ORD, ICAO: KORD, FAA LID: ORD), typically referred to as O'Hare Airport, Chicago O'Hare, or simply O'Hare, is an international airport located on the far Northwest Side of Chicago, Illinois, 14 miles (23 km) northwest of the Loop business district, operated by the Chicago Department of Aviation[6] and covering 7,627 acres (3,087 ha).[4] O'Hare has direct flights to 217 destinations in North America, South America, Asia, Africa, and Europe.[7][8]

Established to be the successor to Chicago’s ”busiest square mile in the world” Midway Airport, O’Hare began as an airfield serving a Douglas manufacturing plant for C-54 military transports during World War II. It was named for Edward "Butch" O'Hare, the U.S. Navy's first Medal of Honor recipient during that war.[9] Later, at the height of the Cold War, O'Hare served as an active fighter base for the Air Force.[10]

As the first major airport planned post-war, O’Hare's innovative design pioneered concepts such as concourses, direct highway access to the terminal, jet bridges, and underground refueling systems.[11] It became famous as the first World’s Busiest Airport of the jet age, holding that distinction from 1963 to 1998; today, it is the world's sixth-busiest airport, serving 79.8 million passengers in 2017.

O'Hare is unusual in that it serves a major hub for more than one of the three U.S. mainline carriers; it is United's largest hub in both passengers and flights, while it is American's third-largest hub.[12][13] It is also a focus city for Frontier Airlines and Spirit Airlines.[2][3]

Today, Terminals 2 and 3 remain of the original design, but O’Hare has been modernizing the airfield since 2005, and is beginning an expansion of passenger facilities that will remake it as North America’s first airport built around airline alliances.[14][15]

History

Establishment and defense efforts

Not long after the opening of Midway Airport in 1926, the City of Chicago realized that additional airport capacity would be needed in the future. The city government investigated various potential airport sites during the 1930s, but made little progress prior to America's entry into World War II.[9]

O'Hare's place in aviation began with a manufacturing plant for Douglas C-54s during WWII. The site was then known as Orchard Place, and had previously been a small German farming community. The 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) plant, located in the northeast corner of what is now the airport property, needed easy access to the workforce of the nation's then second-largest city, as well as its extensive railroad infrastructure and location far from enemy threat. Some 655 C-54s were built at the plant. The attached airfield, from which the completed planes were flown out, was known simply as Douglas Airport; initially, it had four 5,500-foot (1,700 m) runways.[9] Less known is the fact that it was the location of the Army Air Force’s 803rd Specialized Depot[16], a unit charged with storing many captured enemy aircraft. A few representatives of this collection would eventually be transferred to the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum.[17][18]

Douglas Company's contract ended in 1945 and, though consideration was given to building commercial aircraft at Orchard, the company ultimately chose to concentrate commercial production at its original headquarters in Santa Monica, CA.[9] With the departure of Douglas, the complex took the name of Orchard Field Airport, and was assigned the IATA code ORD.[19]

The United States Air Force used the field extensively during the Korean War, at which time there was still no scheduled commercial service at the airport. Although not its primary base in the area, the Air Force used O'Hare as an active fighter base; it was home to the 62nd Fighter-Interceptor Squadron flying F-86 Sabres from 1950 to 1959.[10] By 1960, the need for O'Hare as an active duty fighter base was diminishing, just as commercial business was picking up at the airport. The Air Force removed active-duty units from O'Hare and turned the station over to Continental Air Command, enabling them to base reserve and Air National Guard units there.[20] As a result of a 1993 agreement between the City and the Department of Defense, the reserve based was closed on April 1, 1997, ending its career as the home of the 928th Airlift Wing. At that time, the 357 acre (144 ha) site came under the ownership of the Chicago Department of Aviation.[21]

Commercial development

In 1945, Chicago mayor Edward Kelly established a formal board to choose the site of a new facility to meet future aviation demands. After considering various proposals, the board decided upon the Orchard Field site, and acquired most of the federal government property in March 1946. The military retained a relatively small parcel of property on the site, and the rights to use 25% of the airfield's operating capacity for free.[9]

Ralph H. Burke devised an airport master plan based on the pioneering idea of what he called "split finger terminals", allowing a terminal building to be attached to "airline wings" (concourses), each providing space for gates and planes. (Pre-war airport designs had favored ever-larger single terminals, exemplified by Berlin's Tempelhof.) Other innovations Burke called for included underground refueling, direct highway access to the front of terminals, and direct rail access, all of which are utilized at airports worldwide today. O'Hare was the site of the world's first jet bridge in 1958,[22][23] and successfully adapted slip form paving, developed for the nation's new Interstate highway system, for seamless concrete runways.

In 1949, the City renamed the facility O'Hare Field to honor Edward "Butch" O'Hare, the U.S. Navy's first flying ace and Medal of Honor recipient in World War II.[24] Its IATA code (ORD) remained unchanged, however, resulting in O'Hare's being one of the few IATA codes bearing no connection to the airport's name or metropolitan area.[19]

Scheduled passenger service began in 1955,[25] but growth was slow at first. Although Chicago had invested over $25 million in O'Hare, Midway remained the world's busiest airport and airlines were reluctant to move until highway access and other improvements were completed.[26] The April 1957 Official Airline Guide shows only 36 weekday departures from the airport, while Midway coped with 414. Improvements began to attract the airlines: O'Hare's first dedicated international terminal opened in August 1958, and by April 1959 the airport had expanded to 7,200 acres (2,900 ha) with new hangars, terminals, parking and other facilities. The expressway link to downtown Chicago, now known as the Kennedy Expressway, was completed in 1960.[25] And new Terminals 2 and 3, designed by C. F. Murphy and Associates, opened on January 1, 1962.[27]

However, the biggest factor driving the airlines to O'Hare from Midway was the emergence of commercial jet transports; one-square-mile Midway did not have the space for the lengthy runways the new planes required.[28] While airlines had initially been reluctant to move to O'Hare, they were equally unwilling to split operations between the two airports: in July 1962 the last fixed-wing scheduled airline flight in Chicago moved from Midway to O'Hare. The arrival of Midway's traffic quickly made O'Hare the world's busiest airport, serving 10 million passengers annually. Within two years that number would double, with Chicagoans proudly boasting that more people passed through O'Hare in 12 months than Ellis Island had processed in its entire existence. O'Hare remained the world's busiest airport until 1998.

On January 17, 1980, the airport's weather station became the official point for Chicago's weather observations and records by the National Weather Service, replacing Midway.[29]

Post-deregulation developments and hubs

In the 1980s, after passage of US airline deregulation, the first major change at O'Hare occurred when TWA decamped Chicago for St. Louis as its main mid-continent hub.[30] Although TWA had a large hangar complex at O'Hare and had initiated non-stop service to Europe from Chicago using 707s in 1958, by the time of deregulation its operation was losing $25 million a year under intense competition from United and American.[31] Northwest likewise ceded O'Hare to the competition and shifted to a Minneapolis and Detroit-centered network by the early 1990s following its acquisition of Republic Airlines in 1986.[32] Delta maintained a Chicago hub for some time, even commissioning a new Concourse L in 1983.[33] Ultimately, Delta found competing from an inferior position at O'Hare too expensive and closed its Chicago hub in the 1990s, concentrating its upper Midwest operations at Cincinnati.

The dominant hubs established at O'Hare in the 1980s by United and American continue to operate today. United developed a new two-concourse Terminal 1 (dubbed "The Terminal for Tomorrow"), designed by Helmut Jahn. It was built between 1985 and 1987 on the site of the original Terminal 1; the structure, which includes 50 gates, is best known for its curved glass forms and the connecting underground passage between Concourses B and C.[34] American renovated and expanded its existing facilities in Terminal 3 from 1987 to 1990; these renovations feature a flag-lined entrance hall to Concourses H/K.[35][35]

The demolition of the original Terminal 1 in 1984 to make way for Jahn's design forced a "temporary" relocation of international flights into facilities called "Terminal 4" on the ground floor of the airport's central parking garage. International passengers were then bused to and from their aircraft. Relocation finally ended with the completion of the 21-gate International Terminal in 1993 (now called Terminal 5); it contains all customs facilities. Its location, on the site of the original cargo area and east of the terminal core, necessitated the construction of the Airport Transit System people-mover, which connected the terminal core with the new terminal as well as remote rental and parking lots.[33]

The large consolidating mergers in the airline industry from 2008-2014 left O'Hare's domestic operations simplified: the airport found itself primarily with United mainline in Terminal 1, United Express, Air Canada, and Delta in Terminal 2, and American and smaller carriers in Terminal 3.

Field modernization and reconfiguration

O'Hare's high volume and crowded schedule, along with the vagaries of weather in the upper Midwest, frequently led to major delays; its hub status meant delays could affect airlines system-wide, causing issues for air travel across North America. Official reports at the end of the 1990s ranked O'Hare as one of the worst performing airports in the United States, based on the percentage of delayed flights.[36] The situation was exacerbated by a practice known as banking, in which regional and mainline flights arrive within several narrow windows during each day (facilitating quick transfers but creating temporary congestion) and then made worse by bitter competition between United and American, who combined for over 86% of all operations but initially refused to cooperate to ease the situation. In 2004, facing the imposition of flight limits at O'Hare by the FAA, United and American agreed to modify their flight schedules to help reduce congestion caused by clustered arrivals and departures, mainly by adjusting the schedules of their regional carriers.[37]

While reducing the practice of banking helped, the reality was that the airfield had remained unchanged since the addition of its last new runway (4R/22L) in 1971.[38] The existing three pairs of runways at different angles were meant to allow takeoffs into the wind, but they came at a cost: the various intersecting runways were both dangerous and inefficient. In 2001, the Chicago Department of Aviation committed to a O'Hare Modernization Plan (OMP). Initially estimated at $6.6 billion, the OMP was to be paid by bonds issued against the increase in the passenger facility charge enacted that year as well as federal airport improvement funds.[39] The modernization plan was approved by the FAA in October 2005 and involved a complete reconfiguration of the airfield.

The OMP included the construction of four new runways, the lengthening of two existing runways, and the decommissioning of two older runways in order to give the airport six parallel runways and two crosswind runways in a configuration similar to that used at other large hub airports in Atlanta, Dallas/Fort Worth, and Los Angeles.[14] This was a complete redesign of Burke's basic airfield structure; O'Hare had functioned in a circular manner, with the terminal complex in the center and runways effectively in a triangle around it.[9] Now, O'Hare would be organized into three sections, north to south: the North Airfield, containing three east-west and one crosswind runway and a new cargo area; the terminal complex and ground transportation access in the center; and the South Airfield, again containing three east-west and one crosswind runway and a large cargo area. Construction of the two new airfields and the new cargo area while the space-constrained airport continued full operations presented significant time and capacity challenges.

The OMP was the subject of lengthy legal battles, both with suburbs who feared the new layout's noise implications as well as survivors of persons interred in a cemetery the city proposed to relocate; some of the cases were not resolved until 2011.[14] These, plus the reduction in traffic as a result of the 2008 financial crisis, delayed the OMP's completion; construction of the sixth and final parallel runway (9C/27C)[40] began in 2017. Its completion in 2020, along with an extension of runway 9R/27L to be completed in 2021, will conclude the OMP.[41]

Although construction continues, peak capacity (number of operations/hour) has already increased by 50% and total (all weather) system delays reduced by 57%;[42] after completion of the first two phases of the OMP, on-time arrivals improved from 67.6% to 80.8%.[43] By 2017, O'Hare ranked 14th in on-time performance of the top 30 U.S. airports.[44] Costs of the O'Hare Modernization Plan had risen, by 2015, beyond $8 billion.[45]

Future

On March 28, 2018, the Chicago City Council gave approval to new leases with the airlines, which also contained an agreement to a Terminal Area Plan dubbed O'Hare 21.[15] It marks the first comprehensive redevelopment and expansion of the terminal core in O'Hare's history. The improvements are intended to enable same-terminal transfers between international and domestic flights, enable faster connections, improve facilities and technology for TSA and customs inspections, and modernize and expand landside amenities. The most unusual aspect of the plan is the reorganization of the airport into a Global Alliance Hub, the first in North America; airside connections and layout will be optimized around airline alliances. This will be made possible by the construction of the O’Hare Global Terminal where Terminal 2 currently stands. The Global Terminal and two new satellite concourses will allow for expansion for both American's and United's international operations as well as easy interchange with their various international partners through Oneworld (American) or Star Alliance (United), eliminating the need to exit the secured airside, ride the ATS, and re-clear security at Terminal 5. Delta and its SkyTeam partners, as well as all non-affiliated carriers, will relocate to Terminal 5.

The plan is set to add over three million square feet to the airport's terminals, a new customs processing center in the Global Terminal, 25% more ramp space at gates to accommodate larger aircraft, reconstruction of gates and concourses (new concourses will be a minimum of 120 feet (37 m) wide), and increase the gate count from 185 to 235.[46] Since construction cannot interfere with ongoing operations at the airport, it is scheduled to take place in stages, with the first step (scheduled to begin 2019) being to dig the tunnel that will connect the terminal core with two new satellite concourses.[47] Demolition of Terminal 2 and the subsequent construction of the Global Terminal can only proceed after the completion of the two new satellite concourses, which will provide the gates lost by the demolition of Terminal 2. In addition, construction continues on a nine-gate extension of Terminal 5, to open in 2021. A separate "stinger" extension of Concourse L, with five (eventually eight) new American regional gates, opened to service in April, 2018.[48]

By terms of the agreement between the airlines and the City, total costs of $8.7 billion (2018 est.) for O'Hare 21 are to be borne by bonds issued by the City and retired through airport usage fees paid by the airlines. The O'Hare 21 project is scheduled for completion in 2026.

Infrastructure

Runways

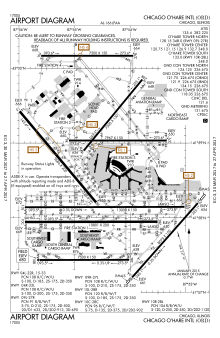

O'Hare is organized into two parallel east-west runways (9L/27R and 9R/27L) on the north side of the airfield (and forthcoming 9C/27C scheduled for completion in 2020), and three parallel east-west runways (10L/28R, 10C/28C, and 10R/28L) on the south side of the airfield. In addition, there are two parallel crosswind runways oriented northeast/southwest (4R/22L, 4L/22R), one on each side of the airfield. Neither can be used without major disruption to the east-west runways; in fact, 4L/22R crosses 9R/27L and the path of forthcoming 9C/27C, making the chances of the crosswind runways being used, at any given time, very low.[49] (Their role is emergency relief and overnight use.) Each side of the airfield has its own ground control tower.

Westbound operations involves the use of Runway 9L/27R for arrivals coming from the north, Runway 9R/27L for either direction, and Runway 10C.28C for arrivals from the south and heavies. Runway 10L/28R is the departure runway mostly used, with Runway 4R/22L for a few flights with a southwest departure.

Eastbound operations involves the use of Runway 9L/27R for arrivals coming from the north, Runway 10C/28C and sometimes Runway 10R/28L for arrivals coming from the south. Runway 10L/28R is the departure runway for southbound departures and all heavy departures, with Runway 9R/27L is the runway for northbound departures.

The last of the runways to close under the OMP, originally 14R/32L, was removed from service March 29, 2018, and the FAA Airport Diagram now designates the remaining sections[50] as taxiway SS.[51] Ironically, it had been the first new runway added by the city to the old Douglas Field layout, and was lengthened and rebuilt with concrete in 1960 to became O'Hare's first jet runway.[9]

O'Hare has a voluntary nighttime (2200–0700) noise abatement program.[52]

ATS, rental lots and remote parking

Passengers within the airport complex are normally able to travel via the free 2.5 mi (4 km)-long automated Airport Transit System (ATS), connecting all four terminals landside and the rental and remote parking lots. However, as part of a larger project, the ATS is undergoing a $310 million modernization and expansion that includes replacing the existing 15-car fleet with 36 new Bombardier vehicles,[53] upgrading the previous infrastructure, and extending the line 2,000 feet (610 m)[54] to the new consolidated rental/parking/transit facility across Mannheim Road. Currently, the modernization means the ATS is shut down from 0500 Monday through 0500 Saturday (with some holiday exceptions), with free shuttle buses providing service when the ATS is not running.[55]

The ATS extension will end at a new consolidated rental/parking/transit center, a facility that will significantly alter ground access to O'Hare. Rental customers will proceed to the new transit/rental center via the ATS, as will customers seeking shuttle transportation to off-airport hotels or parking; travelers accessing long-term parking will also take the ATS. All shuttle bus service to the terminals will end with the opening of the integrated transit center, eliminating 1.3 million vehicle trips a year into the terminal core. The center, scheduled for completion in 2019, is a five-level, 2,500,000-square-foot (230,000 m2) structure containing 4,200 spaces for rental cars and offices for all airport-franchised ("on-airport") rental car firms, as well as 2,676 additional public parking spaces.[56] The center will also connect the ATS and the O'Hare Metra station; currently, a shuttle bus is necessary to transport passengers between the ATS and Metra.

Hotel

The Hilton Chicago O'Hare is between the terminal core and parking garage and is currently the only hotel on airport property. It is owned by the Chicago Department of Aviation and operated under an agreement with Hilton Hotels.

Environmental efforts

In 2011, O'Hare became the first major airport to build an apiary on its property; every summer, it hosts as many as 75 hives and a million bees. The bees are maintained by 30 to 40 ex-offenders with little to no work experience and few marketable skills from the North Lawndale community. They are taught beekeeping but also benefit from the bees' labor, turning it into bottled fresh honey, soaps, lip balms, candles and moisturizers marketed under the beelove product line; products are sold at stores and used by restaurants throughout both Chicago airports.[57] More than 500 persons have completed the program, transferring to jobs in manufacturing, food processing, customer service, and hospitality; the repeat-offender rate is reported to be less than 10%.[58]

O'Hare has used livestock, primarily goats, since 2013 to control vegetation in harder-to-reach areas or on steeper banks as along Willow-Higgins Creek on the airport property. In the summer of 2018, a mix of 30 goats, sheep, and a donkey named Jackson controlled buckthorn, garlic mustard, ragweed and various other invasive species.[59] The livestock assist not only with vegetation removal and control, but also reduce hiding and nesting places for birds that may interfere with safe aircraft operations, and all without food expense or environmental damage.[60]

Other facilities

The USO offers two facilities: one open 24 hours and located before security in Terminal 2, and an additional site behind security in Terminal 3, open 06:00-22:30 daily. Each offers meals, refreshments, TV and quiet rooms, and internet access. Active duty military personnel and their families, as well as new recruits going to Recruit Training Command, are welcome.[62]

The large Postal Service processing facility at O'Hare is located at the far south end of the airfield along Irving Park Road. Being on secured airfield property, it is not open to the public. USPS drop locations are provided in Terminals 1, 3 and 5.

Terminals

O'Hare has four numbered passenger terminals with nine lettered concourses and a total of 191 gates.

With the exception of flights from destinations with U.S. Customs and Border Protection preclearance, all inbound international flights arrive at Terminal 5, as the other terminals do not have customs screening facilities. Several carriers, such as American, Iberia, Lufthansa, and United, have outbound international flights departing from Terminals 1 and 3. This requires that the aircraft arrive and discharge passengers at Terminal 5, after which the empty plane is towed to another terminal for boarding. This is to expedite connections for passengers transferring from domestic flights to those outbound international flights; while Terminals 1, 2, and 3 all allow airside connections, Terminal 5 is separated from the other terminals by a set of taxiways that cross over the airport's access road, requiring passengers to exit security, ride the Airport Transit System, and then re-clear security before boarding.

Terminal 1

Terminal 1 is used for United Airlines flights, including all mainline flights and some United Express operations, as well as departures for Star Alliance partners Lufthansa (except for flight LH437 to Munich, which departs from Terminal 5; B16-B17) and All Nippon Airways (C10). Terminal 1 has 50 gates on two concourses:

- Concourse B – 22 gates

- Concourse C – 28 gates

Concourses B and C are linear concourses located in separate buildings parallel to each other. Concourse B is adjacent to the airport roadway and houses passenger check-in, baggage claim, and security screenings on its landside and aircraft gates on its airside. Concourse C is a satellite terminal with gates on all sides, in the middle of the ramp, and is connected to Concourse B via an underground pedestrian tunnel under the ramp. The tunnel originates between gates B8 and B9 in Concourse B, and ends on Concourse C between gates C17 and C19. The tunnel is illuminated with a neon installation titled Sky's the Limit (1987) by Canadian artist Michael Hayden, which plays an airy and very slow-tempo version of Rhapsody in Blue.

United operates three United Clubs in Terminal 1: one on Concourse B near gate B6, one located near gate B16, and one on Concourse C near gate C16. There is also a United First International Lounge and United Arrivals Suite in Concourse C near gate C18. Additionally, there is a United Polaris Lounge near gate C18.[63]

Terminal 2

Terminal 2 houses Air Canada, Delta and Delta Connection domestic flights, and most United Express operations (although check-ins for United flights take place in Terminal 1). Terminal 2 has 43 gates on two concourses.

- Concourse E – 17 gates

- Concourse F – 24 gates

There is a United Club in Concourse F near gate F8, and a Delta Sky Club in Concourse E near gate E6. US Airways operated out of Terminal 2 until it moved operations to Terminal 3 in 2014 to join its merger partner American.

Terminal 3

Terminal 3 houses all departing and domestic arriving American Airlines and American Eagle flights, as well as departures for Oneworld carriers Iberia and Japan Airlines, plus unaffiliated low-cost carriers. Terminal 3 currently has 80 gates on four concourses:

- Concourse G – 24 gates

- Concourse H – 18 gates

- Concourse K – 16 gates

- Concourse L – 22 gates

Concourses G and L house most American Eagle operated flights, while Concourses H and K house American's mainline operations. American's oneworld partners Japan Airlines and Iberia depart from K19 or K16. Concourse L is also used by non-affiliated airlines Air Choice One, Alaska Airlines, Cape Air, JetBlue, and Spirit.[64]

American Airlines has three Admiral's Clubs in Terminal 3 and one Flagship Lounge. The main Club and Flagship Lounge is located in the crosswalk between concourses H and K at gates H6/K6; the other Admiral's Clubs are located at gates L1 and G8.[65]

Terminal 5

Terminal 5 houses all of O'Hare's international arrivals (excluding flights with Air Canada, American and United from destinations with U.S. border preclearance). Other destinations with preclearance, including flights operated by Aer Lingus and Etihad Airways, arrive at Terminal 5 but are treated as domestic arrivals. With the exception of select Star Alliance and Oneworld carriers that board from Terminal 1 or Terminal 3 respectively, all non-U.S. carriers except Air Canada depart from Terminal 5.

In 2018, Frontier Airlines became the first domestic carrier to move operations to T5 as a part of the ongoing O'Hare 21 plan.[66]

In 2014, Terminal 5 underwent a $26 million amenities improvement project which belatedly adapted the terminal to a post-September 11 layout; the project added dining and retail post-security, including many locally-owned restaurants.[67]

Terminal 5 has 21 gates on one concourse.

- Concourse M – 21 gates

Terminal 5 has several airline lounges, including the Air France - KLM Lounge, British Airways First Class Galleries and Business Class Terraces Lounges, Korean Air Lounge, Scandinavian Airlines Lounge, Swissport Lounge, and Swiss International Air Lines First Class Lounge and Business Class Lounge. The airport's U.S. Customs and Border Protection facility is located at the arrival (lower) level.

Gate M11a is the only gate at O'Hare currently equipped to handle an Airbus A380. In May 2018, British Airways began service with the A380 on one of its daily flights to Heathrow Airport, beginning the first scheduled A380 service (although Lufthansa and Emirates had landed A380s in demonstrations earlier).[68]

Airlines and destinations

Notes:

Cargo

There are two main cargo areas at O'Hare that have warehouse, build-up/tear-down and aircraft parking facilities.

The Cargo Area (now the South Cargo Area) was relocated in the 1980s from the airport's first air cargo facilities, which were located east of the terminal core, where Terminal 5 now stands. Many of the structures in the new Cargo Area then had to be rebuilt, again, to allow for the OMP and specifically runway 10R/28L; as a result, what is now called the South Cargo Area is located between 10R/28L and 10C/28C. These facilities were established mainly by traditional airline-based air cargo; Air France Cargo, American, JAL Cargo, KLM, Lufthansa Cargo, Northwest and United all built purpose-built, freestanding cargo facilities,[132] although most of them now lease the space out to dedicated cargo firms. In addition, the area contains two separate facilities for shipper FedEx and one for UPS.[132]

The Northeast Cargo Area (NEC) is a conversion of the former military base (the Douglas plant area) and is at the northeast corner of the airport property adjacent to Bessie Coleman Drive. It is a new facility designed to increase O'Hare's cargo capacity by 50%. Two buildings currently make up the NEC: a 540,000 square feet (50,000 m2) building completed in 2016,[133] and a 240,000 square feet (22,000 m2) building that was completed in 2017.[134] A third structure, scheduled for completion in 2019, will complete the NEC with another 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) of warehouse space.[135]

The combined capabilities of the cargo areas provide 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of airside cargo space, on four ramps, with parking for 40 wide-body freighters, matched with over 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of landside warehousing capability. O'Hare shipped over 1.9 million tonnes of cargo in 2017, third among major airports in the U.S. The Department of Aviation estimates the value of the yearly shipments at $200 billion.[136]

Statistics

%3B_PH-BFC%40ORD%3B12.10.2011_624bw_(6301323543).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New York–LaGuardia, New York | 1,621,010 | American, Delta, Spirit, United |

| 2 | Los Angeles, California | 1,440,130 | Alaska, American, Spirit, United |

| 3 | San Francisco, California | 1,147,550 | Alaska, American, United |

| 4 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 1,083,640 | American, Spirit, United |

| 5 | Denver, Colorado | 1,005,570 | American, Frontier, Spirit, United |

| 6 | Boston, Massachusetts | 978,210 | American, JetBlue, Spirit, United |

| 7 | Atlanta, Georgia | 888,300 | American, Delta, Spirit, United |

| 8 | Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota | 845,670 | American, Delta, United |

| 9 | Phoenix–Sky Harbor, Arizona | 820,330 | American, Frontier, Spirit, United |

| 10 | Seattle, Washington | 787,560 | Alaska, American, Delta, Spirit, United |

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Annual Change | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,037,444 | American, British Airways, United | ||

| 2 | 887,663 | Air Canada, American, United | ||

| 3 | 685,067 | All Nippon, American, JAL, United | ||

| 4 | 607,328 | Lufthansa, United | ||

| 5 | 522,129 | American, Frontier, Spirit, United | ||

| 6 | 488,015 | Aeroméxico, Interjet, United, Volaris | ||

| 7 | 413,448 | American, Hainan, United | ||

| 8 | 412,485 | American, United, China Eastern | ||

| 9 | 397,559 | Aer Lingus, American, United | ||

| 10 | 393,089 | Air Canada, American, United | ||

| 11 | 331,944 | Cathay Pacific, United | ||

| 12 | 305,317 | Air Canada, United | ||

| 13 | 304,342 | Air France, American, Delta, United | ||

| 14 | 297,918 | Lufthansa, United | ||

| 15 | 276,795 | Asiana, Korean Air | ||

| 16 | 251,141 | KLM, United | ||

| 17 | 245,376 | Etihad Airways | ||

| 18 | 224,654 | Qatar Airways | ||

| 19 | 207,558 | Turkish Airlines | ||

| 20 | 204,539 | Emirates |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Percent of market share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United Airlines | 20,744,000 | 31.75% |

| 2 | American Airlines | 17,487,000 | 26.77% |

| 3 | SkyWest Airlines | 7,491,000 | 11.47% |

| 4 | Envoy Air | 4,926,000 | 7.54% |

| 5 | Spirit Airlines | 2,959,000 | 4.53% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passenger volume | Change over previous year | Aircraft operations | Cargo tonnage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 72,144,244 | 908,989 | 1,640,524.1 | |

| 2001 | 67,448,064 | 911,917 | 1,413,834.4 | |

| 2002 | 66,565,952 | 922,817 | 1,436,385.7 | |

| 2003 | 69,508,672 | 928,691 | 1,601,735.5 | |

| 2004 | 75,533,822 | 992,427 | 1,685,808.0 | |

| 2005 | 76,581,146 | 972,248 | 1,701,446.1 | |

| 2006 | 76,282,212 | 958,643 | 1,718,011.0 | |

| 2007 | 76,182,025 | 926,973 | 1,690,741.6 | |

| 2008 | 70,819,015 | 881,566 | 1,480,847.4 | |

| 2009 | 64,397,782 | 827,899 | 1,198,426.3 | |

| 2010 | 67,026,191 | 882,617 | 1,577,047.8 | |

| 2011 | 66,790,996 | 878,798 | 1,505,217.6 | |

| 2012 | 66,834,931 | 878,108 | 1,443,568.7 | |

| 2013 | 66,909,638 | 883,287 | 1,434,377.1 | |

| 2014 | 70,075,204 | 881,933 | 1,578,330.1 | |

| 2015 | 76,949,336 | 875,136 | 1,742,500.8 | |

| 2016 | 77,960,588 | 867,635 | 1,726,361.6 | |

| 2017 | 79,828,183 | 867,049 | 1,950,137.2 | |

| 2018 (Through July) | 47,516,068 | 515,246 | 1,125,703.5 |

Ground transportation

Rail

O'Hare International Airport is served by the Blue Line of the Chicago "L", which links the airport with the Chicago Loop. The station is located under the parking garage at the terminal core and is connected via underground walkways to Terminals 1-3; access from T5 is via the ATS or alternate shuttle bus.

Road

O'Hare is directly served by Interstate 190, which offers interchanges with Mannheim Road (U.S. 12 and 45), the Tri-State Tollway (Interstate 294), and Interstate 90. I-90 continues as the Kennedy Expressway into downtown Chicago and becomes the Jane Addams Memorial Tollway northwest to Rockford and the Wisconsin state line.

Accidents and incidents

The following is a list of crashes or incidents that happened to planes at O'Hare, on approach, or just after takeoff from the airport.[158]

- On September 17, 1961, Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 706, a Lockheed L-188 Electra, had a mechanical failure in control surfaces and crashed upon takeoff, killing all 37 on board.[159]

- On August 16, 1965, United Airlines Flight 389, a Boeing 727, crashed 30 miles (48 km) east of O'Hare while on approach, killing all 30 on board.[160]

- On March 21, 1968, United Airlines Flight 9963, a Boeing 727, overran runway 9R (now 10L) on take off. All 3 crew on board were injured, and the aircraft was damaged beyond repair.[161]

- On December 27, 1968, North Central Airlines Flight 458, a Convair CV-580, crashed into a hangar at O'Hare, killing 27 on board and one on the ground.[162]

- On December 20, 1972, North Central Airlines Flight 575, a Douglas DC-9, crashed upon takeoff after colliding with Delta Airlines Flight 954, a Convair CV-880 which was taxiing across the active runway; 10 passengers on the DC-9 were killed.[163]

- On May 25, 1979, American Airlines Flight 191, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 on a Memorial Day weekend flight to Los Angeles International Airport, had its left engine detach while taking off from runway 32R, then stalled and crashed into a field some 4,600 feet (1,400 m) feet away. 273 died in the deadliest single-aircraft crash in United States history, and the worst aviation disaster in U.S. history prior to the September 11, 2001 attacks.[164][165]

- On March 19, 1982, a United States Air Force KC-135 Stratotanker crashed upon approach to O'Hare 40 miles (64 km) northwest of the city (near Woodstock, Illinois), killing 27 people on board.[166]

- On February 9, 1998, American Airlines Flight 1340, a Boeing 727, crashed upon landing from Kansas City, injuring 22 passengers.[167]

- On October 28, 2016, American Airlines Flight 383 aborted takeoff after a fire in the right engine of the Boeing 767; 20 passengers and one flight attendant were injured.[168]

Popular culture

Arthur Hailey's novel Airport featured a thinly-disguised O'Hare as "Lincoln International Airport". The novel, adapted into a 1970 film starring Burt Lancaster, Dean Martin, Helen Hayes, Jacqueline Bisset, and George Kennedy, famously featured a stricken airliner seeking to return to a Chicago airport battling a fierce winter storm. Airport, along with other disaster films of the 1970s, provided the inspiration for the successful spoof Airplane! (1980).

Both Allegiant and the film adaptation set the Bureau of Genetic Welfare's headquarters at O'Hare. In the novel, it is stated that the agency stripped equipment from the city and refurbished the terminals into offices, laboratories, and other facilities. A hotel connected to the airport was converted into housing for the members of the bureau. Aircraft are stationed for surveillance and observation purposes. The film version has a futuristic facility built on the ruins of the old airport. Bullfrogs are launched from hangars mounted on the facility, and the rest of the airport's facilities are clearly seen to be heavily damaged or destroyed.

Well-known movies that have filmed scenes at O'Hare include Contagion, Couples Retreat, Home Alone and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, The Jackal (1997), My Best Friend's Wedding, Risky Business, Sleepless in Seattle, U.S. Marshals and Wicker Park. The television series The Amazing Race and Prison Break have each filmed multiple scenes there.[169]

See also

- Golden Corridor, for the region of commerce and industry surrounding O'Hare and extending west along the Jane Addams Memorial Tollway

- List of the world's busiest airports, for a complete list of the busiest airports in the world

References

![]()

- ↑ "Chicago O'Hare International Airport". AirNav, LLC. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- 1 2 Harden, Mark (September 30, 2014). "Frontier Airlines making Chicago's O'Hare a focus". Chicago Business Journal. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- 1 2 Bhaskara, Vinay (October 1, 2014). "Spirit Airlines Adds Two New Routes at Chicago O'Hare". Airways News. Archived from the original on October 3, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- 1 2 FAA Airport Master Record for ORD (Form 5010 PDF), effective March 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Mayor Emanuel Announces Record-Breaking Year for Passengers and Air Cargo at Chicago Airports". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Transportation. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ "About the CDA". flychicago.com. City of Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ "Direct service". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ Associated Press. "O'Hare to offer 1st direct Chicago-to-Africa flights". chicagotribune.com. tronc. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Petchmo, Ian. "The Fascinating History Chicago's O'Hare International Airport: 1920-1960". airwaysmag.com. Airways International Inc. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- 1 2 "62 Fighter Squadron (AETC)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. United States Air Force. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Burley, Paul. "Ralph H. Burke: Early Innovator of Chicago O'Hare International Airport". www.library.northwestern.edu. Northwestern University. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "The fleet and hubs of United Airlines, by the numbers".

- ↑ "Chicago, IL: O'Hare (ORD)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Petchmo, Ian. "The Fascinating History Chicago's O'Hare International Airport: 2000 to Present". www.airwaysmag.com. Airways International, Inc. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- 1 2 Spielman, Fran. "City Council approves $8.5 billion O'Hare expansion plan by 40-to-1 vote". chicago.suntimes.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Early Years: Major Commands" (PDF). Air Force Association. Air Force Association. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ "Messerschmitt Me 262 A-1a Schwalbe (Swallow)". Smithsonian: National Air & Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ "Junkers Ju 388 L-1". Smithsonian: National Air & Space Museum. Smithsonian Institutuion. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- 1 2 "The Wacky Logic Behind Airport Codes". ABC.com. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "ABSTRACT". airforcehistoryindex.org. US Air Force.

- ↑ "1,000 Bid Farewell To O'hare's Air Force Reserve Base". chicagotribune.com. tronc. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Briefings... (pg. 58)". Flying Magazine (Vol, 62, No. 6). Ziff-Davis Publishing Co. Google. June 1, 1958. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ "Airport's Mobile Covered Bridge". Life Magazine (Vol. 44, No. 16). Time-Life Publishing. April 21, 1958.

- ↑ "YESTERDAY'S CITY – Part III". polishnews.com. MH Magazine. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- 1 2 "O'Hare History". Fly Chicago. Chicago Department of Aviation. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Airports for the Jet Age: The U.S. Is Far from Ready". Time Magazine. October 21, 1957. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Break Ground at O'Hare for Terminal Unit". Chicago Daily Tribune. April 2, 1959. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ↑ Knapp, Kevin. "PRECEDENT FOR PEOTONE? PEOTONE BACKERS SAY RICHARD J. DALEY PUSHED FOR O'HARE DESPITE AIRLINE OPPOSITION, PROVING THAT "IF YOU BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME." BUT HISTORY SHOWS IT WASN'T THAT SIMPLE". chicagobusiness.com. Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Station Thread for Chicago Area, IL". ThreadEx. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "TWA Routes". Airways News. January 1, 1987. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "THE AIRLINE BATTLE AT O'HARE". nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "North America Nonstop Routes". Airways News. 1994. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- 1 2 Petchmo, Ian. "The Fascinating History Chicago's O'Hare International Airport: 1960-2000". airwaysmag.com. Airways International, Inc. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ Washburn, Gary (August 4, 1987). "United's Flashy Terminal Ready For Takeoff". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- 1 2 McGovern-Petersen, Laurie (2004). "Chicago O'Hare International Airport". In Sinkevitch, Alice. AIA Guide to Chicago (2nd ed.). Orlando, Florida: Harcourt. p. 278. ISBN 0-15-602908-1. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Chicago, IL: Chicago O'Hare International (ORD)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ Hilkevitch, Jon. "Regional jets jam O'Hare". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ Flightguide Vol. II,Revision 5/71, Airguide Publications/Monty Navarre, Monterrey CA

- ↑ "Lessons Learned From the Chicago O'Hare Modernization Program" (PDF). enotrans.com. Eno Center for Transportation. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ↑ "Runway realignment at O'Hare (map)". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "Map of new runway opened at O'Hare airport". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "FUELING CHICAGO'S ECONOMIC ENGINE: INVESTING IN O'HARE BRINGS BENEFITS TO THE REGION" (PDF). www2.deloitte.com. City of Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "O'Hare's Ranking for On-Time Flights Has Dramatically Improved". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ "Ranking of Major Airport On-Time Arrival Performance in December 2017". BTS.gov. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "O'Hare Modernization Update" (PDF). theconf.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ Byrne, Ruthhart, John, Bill. "$4 billion bond approval earns Emanuel key victory as council green lights O'Hare overhaul". chicagotribune.com. tronc. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Mayor Emanuel and Airlines Sign Historic $8.5 Billion Agreement to Transform Chicago O'Hare International Airport". cityofchicago.org. City of Chicago. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Genter, JT. "9 Things To Know About American Airlines' New Gates at Chicago O'Hare". thepointsguy.com. The Points Guy, LLC. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "O'Hare Modernization Final Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix F, Table F-39" (PDF). faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ von Wedelstaedt, Konstantin. "Aerial photo of O'Hare Airport August 8, 2018". Airliners.net. © Konstantin von Wedelstaedt. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ "KORD Airport Diagram effective March 29 - April 20" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-30. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ "Fly Quiet Program". flychicago.com. City of Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Bombardier to Supply INNOVIA Automated People Mover System to Chicago O'Hare International Airport". bombardier.com. Bombardier Transportation. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-01-07. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ↑ "Temporary Closure of O'Hare Airport Transit System (ATS) Begins On May 30, 2018". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ↑ Spielman, Fran. "Dynamic pricing, frequent parking programs coming to O'Hare Airport". chicago.suntimes.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Baskas, Harriet. "Bee colonies take flight once more, with some help from airport apiaries". cnbc,com. CNBC, LLC. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Apiary: The First Major On-Airport Apiary in the U.S." flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Chicago Department of Aviation Welcomes the Grazing Herd Back to O'Hare". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ↑ "Grazing Herd". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Elliott, Annabel Fenwick (June 25, 2018). "Sleeping in Airports: Is it Allowed? Some Airports are Banning People". Traveller.

- ↑ "USO". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ "United Club & Airport Lounge Locations | United Airlines". www.united.com. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ↑ https://www.airport-ohare.com/flight-departure/9K1525

- ↑ "Chicago O'Hare International Airport (ORD) Admirals Club locations". Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Frontier Airlines Moves to Terminal 5 at O'Hare International Airport". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Karp, Gregory (April 4, 2014). "O'Hare Shows Off Updated International Terminal". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ↑ Zumbach, Lauren. "Airbus A380, world's largest passenger jet, making 1st regular O'Hare flights next year". Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ "TImetables". Aer Lingus.

- ↑ "TImetables". Aeroméxico.

- 1 2 "Flight Schedules". Air Canada.

- ↑ "Air Choice One Destinations". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Air France flight schedule". Air France.

- ↑ "Air India Chicago". Air India.

- ↑ "Air New Zealand Adds Chicago Service From Late Nov 2018". Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flight schedules - Air New Zealand". Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flight Timetable". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "FLIGHT SCHEDULE AND OPERATIONS". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Timetables [International Routes]". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "American Route Changes: New Flights To The Caribbean & Hawaii, Beijing Route Canceled". Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ http://news.aa.com/news/news-details/2018/American-Airlines-Expands-European-Footprint-and-Modifies-Asia-Service/

- ↑ http://news.aa.com/news/news-details/2018/American-Airlines-Expands-European-Footprint-and-Modifies-Asia-Service/

- 1 2 "Flight schedules and notifications". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 https://news.get.com/american-airlines-adds-routes-chicago-and-phoenix/

- ↑ https://www.bizjournals.com/tampabay/news/2018/06/25/american-airlines-to-launch-chicago-service-from.html

- ↑ "Routes of Service". Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Austrian Timetable". Austrian Airlines.

- ↑ "Avianca iniciará vuelos entre Bogotá y Chicago". Aviacol. May 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Check itineraries". Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ https://www.caribbeannewsdigital.com/noticia/avianca-iniciara-vuelos-directos-chicago-desde-guatemala

- ↑ "Bahamasair". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Timetables". British Airways.

- ↑ "Flight Status". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flight Timetable". Cathay Pacific.

- ↑ "Cayman Airways Flight Schedule". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Schedules and Timetable". China Eastern Airlines.

- ↑ "Flight Schedule". Copa Airlines.

- 1 2 "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Delta adds Raleigh – Chicago service from April 2019". Routes Online. July 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Flight Schedules". Emirates.

- ↑ "Schedule - Fly Ethiopian". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flight Timetables". Etihad Airways.

- ↑ "Timetables and Downlaods". EVA Air.

- ↑ "Finnair flight timetable". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ Kelley, Rick. "Frontier Airlines coming to Harlingen airport". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ↑ https://www.bizjournals.com/chicago/news/2018/08/28/frontier-airlines-rapidly-expanding.html

- ↑ "Frontier". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flight times - Iberia". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flight Schedule". Icelandair.

- ↑ "Flight Schedule". Interjet.

- ↑ "Japan Airlines Timetables". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "View the Timetable". KLM.

- ↑ "Flight Status and Schedules". Korean Air.

- ↑ "Timetables". LOT Polish Airlines.

- ↑ "Timetable - Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa.

- ↑ "Norwegian Air Shuttle Destinations". Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Flight timetable". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Route Map". Royal Jordanian Airlines. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ "Timetable - SAS". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Spirit Airlines adds flights from Jacksonville". Action News JAX.

- ↑ "Where We Fly". Spirit Airlines. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Timetable". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Online Flight Schedule". Turkish Airlines.

- 1 2 "Timetable". Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ https://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/united-drops-three-mexican-destinations-448495/

- ↑ "United Airlines to Fly Nonstop from Brownsville to Chicago". www.brownsvilleherald.com.

- ↑ "Vacation Express Non-Stop Flights". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Volaris Flight Schedule". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Route Map". Wow air. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ https://onemileatatime.com/ethiopian-airlines-chicago-addis-ababa/

- 1 2 "Chicago O'Hare International Airport: Advanced Airfield Familiarization Manual" (PDF). flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ Desormeaux, Hailey (2016-12-22). "O'Hare opens new cargo center | News". American Shipper. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ DVV Media Group GmbH. "Chicago opens second phase of cargo expansion ǀ Air Cargo News". Aircargonews.net. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ Burns, Justin. "Chicago O'Hare opens second phase of new cargo facility". aircargoweek.com. Azura International. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Cargo". flychicago.com. Chicago Department of Aviation. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Our Network". Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ "China Southern Cargo Schedule". Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ↑ "SkyCargo Route Map". Emirates SkyCargo. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ↑ Malinowski, Łukasz (February 14, 2012). "Cargo Jet i PLL LOT Cargo uruchomiły trasę z Pyrzowic do Chicago" [Jet Cargo and LOT Polish Airlines Cargo Has Launched a Route from Katowice to Chicago] (Press release) (in Polish). Katowice International Airport. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "The customized AeroLogic network". Aero Logic. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Edmonton adds to cargo load with a regular flight to Tokyo - Edmonton". Globalnews.ca. 2017-08-14. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ Quantas Freight International Network Map (PDF) (Map). Quanta Freight. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Qantas flight QF 7552 schedule". Info.flightmapper.net. April 27, 2016. Retrieved 2016-04-27.

- ↑ "Qantas Freight Launches Chongqing Route". Air Cargo World. April 19, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Qantas Freighter Network Northern Summer Schedule 2010" (PDF). Qantas Freight. June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Qatar Airways to Begin Chicago Freighter Service". AMEinfo. August 2, 2010. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Qatar Airways to begin Chicago freighter service". Air Cargo News. August 10, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar Airways to Start Milan-Chicago Freighter Service". The Journal of Commerce. June 6, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Silk Way Launches Direct Flights to Chicago". September 23, 2016. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Singapore Airlines Cargo". Singapore Airlines Cargo. September 2015. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Turkish freighter goes to Chicago". Air Cargo News. April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Turkish Airlines Cargo added new destinations from 2018". Routesonline.com. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ↑ "Chicago, IL: O'Hare (ORD)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ↑ Office of Aviation Analysis (2014). "U.S. – International Passenger Data for Calendar Year 2014". U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ↑ "RITA | BTS | Transtats". Transtats.bts.gov. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Air Traffic Data". www.flychicago.com. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Chicago–O'Hare International Airport, IL profile". Aviation Safety Network. July 13, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed L-188C Electra N137US Chicago–O'Hare International Airport, IL (ORD)". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 727–22 N7036U Lake Michigan, MI". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft Accident Boeing 727–22 Chicago–O'Hare International Airport". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Convair CV-580 N2045 Chicago–O'Hare International Airport, IL (ORD)". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-31 N954N Chicago–O'Hare International Airport, IL (ORD)". Aviation Safety Network. December 20, 1972. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 N110AA Chicago – O'Hare International Airport, IL (ORD)". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ Franklin, Cory (May 24, 2015). "Commentary: American Airlines Flight 191 still haunts". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing KC-135A-BN Stratotanker 58-0031 Greenwood, IL". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 727 N845AA Chicago–O'Hare International Airport, IL (ORD)". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Uncontained Engine Failure and Subsequent Fire American Airlines Flight 383 Boeing 767-323, N345AN" (PDF). ntsb.gov. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Most Popular Titles With Location Matching "O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, Illinois, USA"". imdb.com. IMDB.com, Inc. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

External links

- Official website

- O'Hare Modernization Program, City of Chicago

- Council Ordinance authorizing O'Hare 21 (with TAP attached, O2018-1124 (V1).pdf), City of Chicago

- Ward Map, City of Chicago

- O'Hare History, Northwest Chicago Historical Society

- The Fascinating History Chicago's O'Hare International Airport: 1920–1960, 1960–2000, 2000 to Present

- Olson, William (January 4, 2010). "Sustainable Airport Design Takes Flight: The O'Hare Modernization Program". GreenBeanChicago.com.

- openNav: ORD / KORD charts

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective October 11, 2018

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KORD

- ASN accident history for ORD

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS latest weather observations

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KORD

- FAA current ORD delay information

- Pate, R. Hewitt (Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division); McDonald, Bruce (Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division); Gillespie, William H. (Economist) (May 24, 2005). "Congestion And Delay Reduction at Chicago O'Hare International Airport: Docket No. FAA-2005-20704". Comments of The United States Department of Justice. Before The Federal Aviation Administration Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 2, 2011.