Film industry

The film industry or motion picture industry, comprises the technological and commercial institutions of filmmaking, i.e., film production companies, film studios, cinematography, animation, film production, screenwriting, pre-production, post production, film festivals, distribution and actors, film directors and other film crew personnel.

Though the expense involved in making films almost immediately led film production to concentrate under the auspices of standing production companies, advances in affordable film making equipment, and expansion of opportunities to acquire investment capital from outside the film industry itself, have allowed independent film production to evolve. Hollywood is the oldest film industry of the world, and the largest in terms of box office gross revenue. Indian cinema (including Bollywood) is the largest film industry in terms of the number of films produced and the number of tickets sold, with 3.5 billion tickets sold worldwide annually (compared to Hollywood's 2.6 billion tickets sold annually)[1] and 1,986 feature films produced annually.[2]

Modern film industry

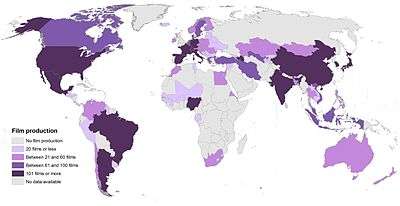

| World cinema |

|---|

The worldwide theatrical market had a box office of US$38.6 billion in 2016. The top three continents/regions by box office gross were: Asia-Pacific with US$14.9 billion, the U.S. and Canada with US$11.4 billion, and Europe, the Middle East and North Africa with US$9.5 billion.[3][4] As of 2016, the largest markets by box office were, in decreasing order, the United States, China, Japan, India, and the United Kingdom. As of 2011, the countries with the largest number of film productions were India, Nigeria, and the United States.[5] In Europe, significant centers of movie production are France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom.[6]

Distinct from the centers are the locations where movies are filmed. Because of labor and infrastructure costs, many films are produced in countries other than the one in which the company which pays for the film is located. For example, many U.S. movies are filmed in Canada, many Nigerian movies are filmed in Ghana, while many Indian movies are filmed in the Americas, Europe, Singapore etc.

United States

.jpg)

The cinema of the United States, often generally referred to as Hollywood, has had a profound effect on cinema across the world since the early 20th century. The United States cinema (Hollywood) is the oldest film industry in the world which originated more than 121 years ago and also the largest film industry in terms of revenue. Hollywood is the primary nexus of the U.S. film industry with established film study facilities such as the American Film Institute, LA Film School and NYFA being established in the area.[7] However, four of the six major film studios are owned by East Coast companies. The major film studios of Hollywood including Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 20th Century Fox, Paramount Pictures and Lightstorm Entertainment are the primary source of the most commercially successful movies in the world, such as Star Wars (1977), and Titanic (1997).

American film studios today collectively generate several hundred movies every year, making the United States one of the most prolific producers of films in the world. Only The Walt Disney Company — which owns the Walt Disney Studios — is fully based in Southern California.[8] And while Sony Pictures Entertainment is headquartered in Culver City, California, its parent company, the Sony Corporation, is headquartered in Tokyo, Japan. Most shooting now takes place in California, New York, Louisiana, Georgia and North Carolina. Hollywood is the most popular film industry with the highest number of screens, and is the highest-grossing film industry in the world. Between 2009-2015, Hollywood consistently grossed $10 billion (or more) annually.[9] Hollywood's award ceremony, the Academy Awards, officially known as The Oscars, is held by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) every year and a total of 2,947 Oscars have been awarded since the inception of the award.[10]

The earliest documented account of an exhibition of projected motion pictures in the United States was in June 1894 in Richmond, Indiana by Charles Francis Jenkins which makes United States cinema the earliest cinema in the whole world. Jenkins used his Phantoscope to project his film before an audience of family, friends and reporters. The film featured a vaudeville dancer performing a Butterfly Dance. Jenkins and his new partner Thomas Armat modified the Phantoscope for exhibitions in temporary theaters at the Cotton States Exposition in the fall of 1895. The Phantoscope was later sold to Thomas Edison, who changed the name of the projector to Edison's Vitascope.

Nestor Studios was Hollywood's first movie studio, founded on 27 October 1911. It was built by David Horsley for Nestor Motion Picture Company. It was then owned and operated by David Horsley and his brother, William Horsley. The first motion picture stage in Hollywood was built behind the tavern. Other East Coast studios had moved production to Los Angeles, prior to Nestor's move west. The California weather allowed for year-round filming and the ambitious studio operated three principal divisions under its Canadian-born general manager, Al Christie. Other filmmakers began opening studios in the Hollywood area. The Horsleys operated the Nestor Studios at the Sunset and Gower location until 20 May 1912, when the Universal Studios was formed, headed by Carl Laemmle. Nestor, along with several other motion picture companies, including Laemmle's Independent Moving Pictures (IMP), was merged with Universal.

China

The Cinema of China is one of three distinct historical threads of Chinese-language cinema together with the cinema of Hong Kong and the cinema of Taiwan. Cinema was introduced in China in 1896 and the first Chinese film, The Battle of Dingjunshan, was made in 1905, with the film industry being centered on Shanghai in the first decades. China is the home of the largest film studio in the world, the Hengdian World Studios, and in 2010 it had the third largest film industry by number of feature films produced annually. For the next decade the production companies were mainly foreign-owned, and the domestic film industry was centered on Shanghai, a thriving entrepot and the largest city in the Far East. In 1913, the first independent Chinese screenplay, The Difficult Couple, was filmed in Shanghai by Zheng Zhengqiu and Zhang Shichuan.[11]

As the Sixth Generation gained international exposure, many subsequent movies were joint ventures and projects with international backers, but remained quite resolutely low-key and low budget. Jia's Platform (2000) was funded in part by Takeshi Kitano's production house,[12] while his Still Life was shot on HD video. Still Life was a surprise addition and Golden Lion winner of the 2006 Venice International Film Festival. Still Life, which concerns provincial workers around the Three Gorges region, sharply contrasts with the works of Fifth Generation Chinese directors like Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige who were at the time producing House of Flying Daggers (2004) and The Promise (2005). It featured no star of international renown and was acted mostly by non-professionals. In 2012 the country became the second-largest market in the world by box office receipts. In 2014, the gross box office in China was ¥29.6 billion (US$4.82 billion), with domestic films having a share of 55%. The country is predicted to have the largest market in the world in 2017 or 2018.[13][14] China has also become a major hub of business for Hollywood studios.[15][16] In 2013, China's gross box office was ¥21.8 billion (US$3.6 billion), the second-largest film market in the world by box office receipts[17] whereas in 2014, China's box office gross was $4.8 Billion, being the second largest box office grosser in film industry.[18]

United Kingdom

India

India is the largest producer of films in the world and second oldest film industry in the world which originated around about 105 years ago.[19] In 2009 India produced a total of 2,961 films on celluloid; this figure includes 1,288 feature films.[20] Besides being the largest producer of films in the world, India also has the largest number of admissions.[21] Indian film industry is multi-lingual and the largest in the world in terms of ticket sales but 3rd largest in terms of revenue mainly due to having amongst the lowest ticket prices in the world.[22] The industry is viewed mainly by a vast film-going Indian public, and Indian films have been gaining increasing popularity in the rest of the world—notably in countries with large numbers of expatriate Indians. Indian film industry is also the dominant source of movies and entertainment in its neighboring countries of South Asia. The largest film and most popular industry in India is the Hindi film industry mostly concentrated in Mumbai (Bombay),[23] and is commonly referred to as Bollywood, an amalgamation of Bombay and Hollywood.

The other largest film industries are Tamil cinema, Telugu cinema, Kannada cinema, Malayalam cinema, and Bangla cinema (cinema of West Bengal), which are located in Chennai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Kochi, and Kolkata. The remaining majority portion is spread across northern, western, and southern India (with Gujarati, Punjabi, Marathi, Oriya, Bhojpuri, Assamese Cinema). However, there are several smaller centers of Indian film industries in regional languages centered in the states where those languages are spoken. Indian films are made filled with musicals, action, romance, comedy, and an increasing number of special effects. It encloses a number of several artforms like Indian classical music, folk music of different regions throughout the country, Indian classical dance, folk dance and much more. It is even the place for number of artists from the Indian subcontinent to showcase their talent. The Indian film industry produces more than 1000 films a year. Bollywood is the largest portion of this and is viewed all over the Indian Subcontinent, and is increasingly popular in UK, United States, Australia, New Zealand, Southeast Asia, Africa, the Gulf countries, European countries and China. The largest film studio complex in the world is Ramoji Film City located at Hyderabad, India, which opened in 1996 and measures 674 ha (1,666 acres). Comprising 47 sound stages, it has permanent sets ranging from railway stations to temples.[24]

Bollywood represents 43% of Indian net box office revenue, while Telugu and Tamil cinema represent 36%, and the rest of the regional cinema constitute 21%, as of 2014.[25]

The highest-grossing movie of India is Dangal which is also the 5th highest grossing non-English movie in the world.

Nigeria

The cinema of Nigeria, often referred to informally as Nollywood, was the second largest film industry, in terms of output, in 2009 and the third largest, in terms of overall revenues generated, in 2013.[26][27] Its history dates back to as early as the late 19th century and into the colonial era in the early 20th century. The history and development of the Nigerian motion picture industry is sometimes generally classified in four main eras: the Colonial era, Golden Age, Video film era and the emerging New Nigerian cinema.[28]

Film as a medium first arrived Nigeria in the late 19th century, in the form of peephole viewing of motion picture devices.[29] These were soon replaced in the early 20th century with improved motion picture exhibition devices, with the first set of films screened at the Glover Memorial Hall in Lagos from 12 to 22 August 1903.[30] The earliest feature film made in Nigeria is the 1926 Palaver produced by Geoffrey Barkas; the film was also the first film ever to feature Nigerian actors in speaking roles.[31][32] The first film entirely copyrighted to the Nigerian Film unit is Fincho (1957) by Sam Zebba; which is also the first Nigerian film to be shot in colour.[33]

After Nigeria's independence in 1960, the cinema business rapidly expanded, with new cinema houses being established.[34] As a result, Nigerian content in theatres increased in the late 1960s into the 1970s, especially productions from Western Nigeria, owing to former theatre practitioners such as Hubert Ogunde and Moses Olaiya transitioning into the big screen.[35] In 1972, the Indigenization Decree was issued by Yakubu Gowon, which demands the transfer of ownership of about a total of 300 film theatres from their foreign owners to Nigerians, which resulted in more Nigerians playing active roles in the cinema and film.[36] The oil boom of 1973 through 1978 also contributed immensely to the spontaneous boost of the cinema culture in Nigeria, as the increased purchasing power in Nigeria made a wide range of citizens to have disposable income to spend on cinema going and on home television sets.[37]

After the decline of the Golden era, Nigerian film industry experienced a second major boom in the 1990s, supposedly marked by the release of the direct-to-video film Living in Bondage (1992); the industry peaked in the mid 2000s to become the second largest film industry in the world in terms of the number of annual film productions, placing it ahead of the United States and behind only India.[26] The films started dominating screens across the African continent and by extension, the Caribbeans and the diaspora,[38] with the movies significantly influencing cultures, and the film actors becoming household names across the continent. The boom also led to a backlash against Nigerian films in several countries, bordering on theories such as the "Nigerialization of Africa".[39][40] Since the mid-2000s, the Nigerian cinema have undergone some restructuring to promote quality and professionalism, with The Figurine (2009) widely regarded as marking the major turn around of contemporary Nigerian cinema. There has since been a resurgence in the proliferation of cinema establishments, and a steady return of the cinema culture in Nigeria.[41]

The 2016 film The Wedding Party, directed by Kemi Adetiba, is the highest grossing Nollywood film of all time.

Egypt

Since 1976, Cairo has held the annual Cairo International Film Festival (CIFF), which is accredited by the International Federation of Film Producers Association. In 1996, the Egyptian Media Production City (EMPC) was inaugurated in 6th of October City south of Cairo, although by 2001, only one of 29 planned studios was operational.[42] Censorship, formerly an obstacle to freedom of expression, has decreased remarkably by 2012, when the Egyptian cinema had begun to tackle boldly issues ranging from sexual issues[43] to heavy government criticism.[44]

The 1940s, 1950s and the 1960s are generally considered the golden age of Egyptian cinema. As in the West, films responded to the popular imagination, with most falling into predictable genres (happy endings being the norm), and many actors making careers out of playing strongly typed parts. In the words of one critic, "If an Egyptian film intended for popular audiences lacked any of these prerequisites, it constituted a betrayal of the unwritten contract with the spectator, the results of which would manifest themselves in the box office."[45] Since the 1990s, Egypt's cinema has gone in separate directions. Smaller art films attract some international attention but sparse attendance at home. Popular films, often broad comedies such as What A Lie!, and the extremely profitable works of comedian Mohamed Saad, battle to hold audiences either drawn to Western films or, increasingly, wary of the perceived immorality of film.[46]

Iran

The cinema of Iran (Persian: سینمای ایران) or cinema of Persia refers to the cinema and film industries in Iran which produce a variety of commercial films annually. Iranian art films have garnered international fame and now enjoy a global following.[47]

Along with China, Iran has been lauded as one of the best exporters of cinema in the 1990s.[48] Some critics now rank Iran as the world's most important national cinema, artistically, with a significance that invites comparison to Italian neorealism and similar movements in past decades.[47] A range of international film festivals have honored Iranian cinema in the last twenty years. Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke and German filmmaker Werner Herzog have praised Iranian cinema as one of the world's most important artistic cinemas.[49]

Japan

See Cinema of Japan

Korea

The term "cinema of Korea" (or "Korean cinema") encompasses the motion picture industries of North and South Korea. As with all aspects of Korean life during the past century, the film industry has often been at the mercy of political events, from the late Joseon dynasty to the Korean War to domestic governmental interference. While both countries have relatively robust film industries today, only South Korean films have achieved wide international acclaim. North Korean films tend to portray their communist or revolutionary themes.

South Korean films enjoyed a "Golden age" during the late 1950s, and 1960s, but by the 1970s had become generally considered to be of low quality. Nonetheless, by 2005 South Korea had become one of few nations to watch more domestic than imported films in theatres[50] due largely to laws placing limits on the number of foreign films able to be shown per theatre per year.[51] In the theaters, Korean films must be played for 73 days per year since 2006. On cable TV 25% domestic film quota will be reduced to 20% after KOR-US FTA.[52] The cinema of South Korea had a total box office gross in the country in 2015 of ₩884 billion and had 113,000,000 admissions, 52% of the total admissions.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is a filmmaking hub for the Chinese-speaking world (including the worldwide diaspora) and East Asia in general. For decades it was the third largest motion picture industry in the world (after Bollywood and Hollywood) and the second largest exporter of films.[53] Despite an industry crisis starting in the mid-1990s and Hong Kong's return to Chinese sovereignty in July 1997 Hong Kong film has retained much of its distinctive identity and continues to play a prominent part on the world cinema stage. Unlike many film industries, Hong Kong has enjoyed little to no direct government support, through either subsidies or import quotas. It has always been a thoroughly commercial cinema, concentrating on crowd-pleasing genres, like comedy and action, and heavily reliant on formulas, sequels and remakes. Typically of commercial cinemas, its heart is a highly developed star system, which in this case also features substantial overlap with the pop music industry.

Turkey

The Yeşilçam film industry is the second largest European theatrical growth market and the 7th largest theatrical market in terms of admissions, only superseded by the ‘big 5’ EU markets and the Russian Federation. The Turkish film market also stands out in the pan-European landscape as the only market where national films regularly outperform US films.[54] It had 1.2 million number of admissions in film industry and 87 feature films were released in the year 2013.[55] Because of the exceptional box office success of Turkish films on the domestic market, the estimated 12.9 million admissions generated on non-national European markets only account for 7% of total admissions to Turkish films in Europe (including Turkey) between 2004 and 2013. This is the third lowest share among the 30 European markets for which such data are available and clearly illustrates the strong dependence of Turkish films on the domestic market, a feature which is shared by Polish and Russian films.[56]

Over the past ten years an increasing number of Turkish films and filmmakers have been selected for international film festivals and received a large number of awards, like Kış Uykusu (Winter's Sleep) won Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Film in 2014.[57] In terms of box office Turkey still ranks behind the Netherlands with just over EUR 200 million as Europe's eight largest box office market ahead of Sweden and Switzerland with a clear gap to the top 6 markets all of which registered GBO between EUR 504 million (Spain) up to over EUR 1 billion in France, the UK, Germany and the Russian Federation.[58] Cinema going is comparatively cheap in Turkey. In 2013 a cinema ticket cost on average EUR 4.0 in Turkey, and this is estimated to be the lowest average ticket price - measured in Euro - in Europe, marginally cheaper than in several Central and Eastern European markets like Croatia, Romania, Lithuania or Bulgaria.[59] When comparing ticket prices in Euro, one of course has to take into consideration that these comparisons are significantly affected by fluctuations in the exchange rates of the various currencies. Because of devaluation of the Turkish Lira against the Euro, average ticket prices measured in Euro remained fairly stable over the past 10 years.[59]

Pakistan

The cinema of Pakistan, or simply, Pakistani cinema (Urdu: پاکستانی سنیما) refers to Pakistan's film industry. Most of the feature films shot in Pakistan are in Urdu, the national language, but may also include films in English, the official language, and regional languages such as Punjabi, Pashto, Balochi, and Sindhi. Lahore has been described as the epicentre of Pakistani cinema, giving rise to the term "Lollywood."

Before the separation of Bangladesh, Pakistan had three main film production centres: Lahore, Karachi and Dhaka. The regime of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, VCRs, film piracy, the introduction of entertainment taxes, strict laws based upon ultra-conservative jurisprudence, was an obstacle to the industry's growth.[60] Once thriving, the cinema in Pakistan had a sudden collapse in the 1980s and by the 2000s "an industry that once produced an average of 80 films annually was now struggling to even churn out more than two films a year.".[61][62] However, the industry has recently made a dramatic and remarkable comeback, evident from the fact that 18 of the 21 highest grossing Pakistani movies were released from 2013 through to the present, with Pakistani films frequently outcompeting Bollywood movies for the Pakistani audience, the industry is supported by Pakistani channels such as ARY and Geo whose entertainment divisions have invested significantly in Pakistani cinema when expanding from providing news and entertainment on TV channels, the lifting of strict regulations on production of films and reduction of taxes on cinemas helped to fuel an expansion across the industry from which the film industry has seen a revival.

Bangladesh

The cinema of Bangladesh is the Bengali language film industry based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The industry often has been a significant film industry since the early 1970s. The word "Dhallywood" is a portmanteau of the words Dhaka and Hollywood. The dominant style of Bangladeshi cinema is Melodramatic cinema, which developed from 1947 to 1990 and characterizes most films to this day. Cinema was introduced in Bangladesh in 1898 by Bradford Bioscope Company, credited to have arranged the first film release in Bangladesh. Between 1913 and 1914, the first production company named Picture House was opened. A short silent film titled Sukumari (The Good Girl) was the first produced film in the region during 1928. The first full-length film The Last Kiss, was released in 1931. From the separation of Bangladesh from Pakistan, Dhaka is the center of Bangladeshi film industry, and generated the majority share of revenue, production and audiences. The 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and the first half of the 1990s were the golden years for Bangladeshi films as the industry produced many successful films. The Face and the Mask, the first Bengali language Bangladeshi full-length feature film was produced in 1956.[63][64]

Directors such as Fateh Lohani, Zahir Raihan, Alamgir Kabir, Khan Ataur Rahman, Subhash Dutta, Ritwik Ghatak, Ehtesham, Chashi Nazrul Islam, Abdullah al Mamun, Sheikh Niamat Ali, Gazi Mazharul Anwar, Tanvir Mokammel, Tareque Masud, Morshedul Islam, Humayun Ahmed, Gias Uddin Selim, Amitabh Reza Chowdhury and others have made significant contributions to Bangladeshi mainstream cinema, parallel cinema, art films and won global acclaim.

Indonesia

The biggest film studios in Southeast Asia has been soft opened on 5 November 2011 on 10 hectares of land in Nongsa, Batam Island, Indonesia. Infinite Frameworks (IFW) is a Singapore-based company (closed to Batam Island) which is owned by a consortium with 90 percent of it hold by Indonesian businessman and movie producer, Mike Wiluan.[65] In 2010-2011, due to the substantial increase in value added tax applied to foreign films, cinemas no longer had access to many foreign films, including Oscar-winning films. Foreign films include major box offices from the west, and other major film producers of the world. This has caused a massive ripple effect on the country's economy. It is assumed that this increases the purchase of unlicensed DVDs. However, even copyright violating DVDs took longer to obtain. The minimum cost to view a foreign film not screened locally, was 1 million Rupiah. This is equivalent to US$100, as it includes a plane ticket to Singapore.[66]

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago's film sector began emerging in the late fifties to early sixties and by the late seventies, there were a handful of local productions, both feature film and television.[67] The first full-length feature film to be produced in Trinidad and Tobago was “The Right and the Wrong” (1970) by Indian director/writer/producer, Harbance Kumar. The screenplay was written by the Trinidadian playwright, Freddie Kissoon.[68] The rest of the 20th century saw a couple more feature films being made in the country, with “Bim” (1974), being singled out by Bruce Paddington as "one of the most important films to be produced in Trinidad and Tobago….and one of the classics of Caribbean cinema.”[69] It was one of the first films to feature an almost entirely Trinidadian cast and crew.[70] There was a rise in Trinidadian film production in the 2000s. Movies such as “Ivan the Terrible” (2004), “SistaGod” (2006), “I’m Santana: The Movie” (2012) and “God Loves the Fighter” (2013) were released both locally and internationally. “SistaGod” had its world premiere at the 2006 Toronto International Film Festival.[71]

The Trinidad and Tobago Film Company is the national agency that was established in 2006 to further development of the film industry. Trinidad and Tobago puts on a number of film festivals which are organized by different committees and organizations. These include the Secondary Schools Short Film Festival and Smartphone Film Festival organized by Trinidad and Tobago Film Company. There is also an annual Trinidad and Tobago Film Festival which runs for two weeks in the latter half of September.

Nepal

Nepali film does not have a very long movie history, but the industry has its own place in the cultural heritage of the country. It is often referred to as 'Nepali Chalchitra' (which translates to "Nepali movies" in English). The terms Kollywood and Kallywood are also used, as a portmanteau of "Kathmandu" and "Hollywood"; "Kollywood" however is more frequently used to refer to Tamil cinema.[1] Chhakka Panja has been considered the highest-grossing movie of all time in Nepali Movie Industry and Kohinoor the second highest. Nepali movies has recently begun receiving international acclaim with films such as The Black Hen (2015), Kagbeni (2006) and others. Nepali feature film White Sun (Seto Surya) has bagged the Best Film award at the 27th Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF)(2016).

The Film Development Board (FDB) was established by the Government of Nepal for the development and promotion of the Nepali film industry. The Board is a liaison to facilitate the conceptualization, making, distribution and exhibition of Nepali films nationally. The Board attempts to bridge the gap between film entrepreneurship and government bureaucracy. The Board is a balance between the people at large, the government, and the process of film making. It is intended to act as the safeguard of the interests of the people, the watchdog of the government, and the advocate of filmmakers.

History

The first feature film to be made was the 1906 Australian silent The Story of the Kelly Gang, an account of the notorious gang led by Ned Kelly that was directed and produced by the Melburnians Dan Barry and Charles Tait. It ran, continuously, for eighty minutes.[72]

In the early 1910s, the film industry had fully emerged with D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation. Also in the early 1900s motion picture production companies from New York and New Jersey started moving to California because of the good weather and longer days. Although electric lights existed at that time, none were powerful enough to adequately expose film; the best source of illumination for movie production was natural sunlight. Besides the moderate, dry climate, they were also drawn to the state because of its open spaces and wide variety of natural scenery.

Another reason was the distance of Southern California from New Jersey, making it more difficult for Thomas Edison to enforce his motion picture patents. At the time, Edison owned almost all the patents relevant to motion picture production and, in the East, movie producers acting independently of Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company were often sued or enjoined by Edison and his agents. Thus, movie makers working on the West Coast could work independently of Edison's control. If he sent agents to California, word would usually reach Los Angeles before the agents did and the movie makers could escape to nearby Mexico.

Hollywood

The earliest documented account of an exhibition of projected motion pictures in the United States was in June 1894 in Richmond, Indiana by Charles Francis Jenkins. The first movie studio in the Hollywood area, Nestor Studios, was founded in 1911 by Al Christie for David Horsley in an old building on the northwest corner of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street. In the same year, another fifteen Independents settled in Hollywood. Hollywood came to be so strongly associated with the film industry that the word "Hollywood" came to be used colloquially to refer to the entire industry.

In 1913 Cecil B. DeMille, in association with Jesse Lasky, leased a barn with studio facilities on the southeast corner of Selma and Vine Streets from the Burns and Revier Studio and Laboratory, which had been established there. DeMille then began production of The Squaw Man (1914). It became known as the Lasky-DeMille Barn and is currently the location of the Hollywood Heritage Museum.

The Charlie Chaplin Studios, on the northeast corner of La Brea and De Longpre Avenues just south of Sunset Boulevard, was built in 1917. It has had many owners after 1953, including Kling Studios, which housed production for the Superman TV series with George Reeves; Red Skelton, who used the sound stages for his CBS TV variety show; and CBS, who filmed the TV series Perry Mason with Raymond Burr there. It has also been owned by Herb Alpert's A&M Records and Tijuana Brass Enterprises. It is currently The Jim Henson Company, home of the Muppets. In 1969 The Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board named the studio a historical cultural monument.

The famous Hollywood Sign originally read "Hollywoodland." It was erected in 1923 to advertise a new housing development in the hills above Hollywood. For several years the sign was left to deteriorate. In 1949 the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce stepped in and offered to remove the last four letters and repair the rest.

The sign, located at the top of Mount Lee, is now a registered trademark and cannot be used without the permission of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, which also manages the venerable Walk of Fame.

The first Academy Awards presentation ceremony took place on 16 May 1929, during a banquet held in the Blossom Room of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on Hollywood Boulevard. Tickets were USD $10.00 and there were 250 people in attendance.

From about 1930 five major Hollywood movie studios from all over the Los Angeles area, Paramount, RKO, 20th Century Fox, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Warner Bros., owned large, grand theaters throughout the country for the exhibition of their movies. The period between the years 1927 (the effective end of the silent era) to 1948 is considered the age of the "Hollywood studio system", or, in a more common term, the Golden Age of Hollywood. In a landmark 1948 court decision, the Supreme Court ruled that movie studios could not own theaters and play only the movies of their studio and movie stars, thus an era of Hollywood history had unofficially ended. By the mid-1950s, when television proved a profitable enterprise that was here to stay, movie studios started also being used for the production of programming in that medium, which is still the norm today.

Bollywood

Bollywood is the Hindi-language film industry based in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), Maharashtra, India. The term is often incorrectly used to refer to the whole of Indian cinema; however, it is only a part of the total Indian film industry, which includes other production centres producing films in multiple languages.[73] Bollywood is the largest film producer in India and one of the largest centres of film production in the world.[74][75][76]

Bollywood is formally referred to as Hindi cinema.[77] Linguistically, Bollywood films tend to use a colloquial dialect of Hindi-Urdu, or Hindustani, mutually intelligible to both Hindi and Urdu speakers,[78][79][80] while modern Bollywood films also increasingly incorporate elements of Hinglish.[78]

The Wrestlers (1899) and The Man and His Monkeys (1899), directed and produced by Harischandra Sakharam Bhatawdekar (H. S. Bhatavdekar), were the first two films made by Indian filmmakers, which were both short films. He was also the first Indian filmmaker to direct and produce the first documentary and news related film, titled The Landing of Sir M.M. Bhownuggree.

Pundalik (Shree Pundalik) (1912), by Dadasaheb Torne alias Rama Chandra Gopal, and Raja Harishchandra (1913), by Dadasaheb Phalke, were the first and second silent feature films respectively made in India.[81][82][83][84] By the 1930s the industry was producing more than 200 films per annum.[85] The first Indian sound film, Ardeshir Irani's Alam Ara (1931), was a major commercial success.[86] There was clearly a huge market for talkies and musicals; Bollywood and all the regional film industries quickly switched to sound filming. Joymoti (1935 film) by Jyoti Prasad Agarwalla was the first Indian dubbed film, released in Calcutta on 10 March 1935. Till then, all dialogues of all talkies were had to be recorded at locations during the shooting of the film. Through Joymoti (1935 film), dubbing technology was successfully introduced to Indian cinema by Assamese filmmaker Jyoti Prasad Agarwalla.[82]

The 1930s and 1940s were tumultuous times: India was buffeted by the Great Depression, World War II, the Indian independence movement, and the violence of the Partition. Most Bollywood films were unabashedly escapist, but there were also a number of filmmakers who tackled tough social issues, or used the struggle for Indian independence as a backdrop for their plots.[85]

In 1937 Ardeshir Irani, of Alam Ara fame, made the first colour film in Hindi, Kisan Kanya. The next year, he made another colour film, a version of Mother India. However, colour did not become a popular feature until the late 1950s. At this time, lavish romantic musicals and melodramas were the staple fare at the cinema.

Following India's independence, the period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s is regarded by film historians as the "Golden Age" of Hindi cinema.[87][88][89] Defining key figures during this time included Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt,[90] Mehboob Khan,[91][92][93] and Dilip Kumar.[94][95]

The 1970s was when the name "Bollywood" was coined,[96][97] and when the quintessential conventions of commercial Bollywood films were established.[98] Key to this was the emergence of the masala film genre, which combines elements of multiple genres (action, comedy, romance, drama, melodrama, musical). The masala film was pioneered in the early 1970s by filmmaker Nasir Hussain,[99] along with screenwriter duo Salim-Javed, pioneering the Bollywood blockbuster format.[98]

Economics

Profitability of a film studio is crucially dependent on picking the right film projects and involving the right management and creative teams (cast, direction, visual design, score, photography, costume, set design, editing, and many additional specialties), but it also depends heavily on choosing the right scale and approach to film promotion, control over receipts through technologies such as digital rights management (DRM), sophisticated accounting practices, and management of ancillary revenue streams; in the extreme, for a major media franchise centered on film, the film might itself be only one large component of many large contributions to total franchise revenue.

Substantial revenues might also derive from licensing efforts and other activities centered around the management of intellectual property; for this reason, various national film industries are heavily invested in the politics and legal specifics of multilateral trade agreements. Hollywood is a large enough industry to impact America's net balance of trade, offsetting some of the decline of employment in the manufacturing sector of the American economy since the early 1980s; typical of recent economic trends in first world economies, a large number of manufacturing jobs paying moderate wages are offset by a smaller number of creating jobs paying high wages. As an intellectual property industry, the film industry (along with the software industry) are central to modern globalization.

The film industry differs from software, however, in functioning primarily as a cultural export. English-language culture is the most globalized of all cultures, despite China and India having internal populations to rival the global English footprint. For this reason, Hollywood is the dominant film industry in globalism and trade. India has both a large film industry and a large, internal English-language culture, though Bollywood has not yet become a center for English-language film exports on a major scale. Films designed for global export tend to be films centered on action rather than dialogue, especially nuanced dialogue which is not fully available to people speaking English as a second language (ESL). Unusually, Japanese Anime has a global audience, though these are sometimes dubbed into English by star-power Hollywood voice actors.

On the creative side, picking the right projects has traditionally been regarded as high risk. Increasingly the risk is being mitigated with approaches drawn from advanced data analytics, such as using models derived from machine learning (sometimes glorified as AI) to estimate the future revenue of a proposed project.[100]

Statistics

Largest industries by number of film productions

The following is a list of the top 15 countries by the number of feature films (fiction, animation and documentary) produced, as determined by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics as of 2015,[101] unless otherwise noted.

| Rank | Country | Films | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,986 | 2017[2] | |

| 2 | 997 | 2011 | |

| 3 | 791 | 2015 | |

| 4 | 686 | 2015 | |

| 5 | 594 | 2017[102] | |

| 6 | 300 | 2015 | |

| 7 | 298 | 2015 | |

| 8 | 269 | 2015 | |

| 9 | 255 | 2015 | |

| 10 | 226 | 2015 | |

| 11 | 185 | 2015 | |

| 12 | 182 | 2015 | |

| 13 | 176 | 2017 [103] | |

| 14 | 137 | 2015 | |

| 15 | 129 | 2015 |

Largest markets by box office revenue

| Rank | Country | Box office revenue (billion US$) | Year | Box office from national films[104] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | World | 40.6 | 2017[105] | N/A |

| 1 | 10.24 | 2017[106] | 88.8% (2015) | |

| 2 | 8.59 | 2017[107] | 53.84% (2017)[107] | |

| 3 | 2.39 | 2017[108] | 85% (2015) | |

| 4 | 2.25 | 2017[106] | 54.9% (2017)[102] | |

| 5 | 1.73 | 2017[106] | 44.3% (2015) | |

| 6 | 1.52 | 2017[106] | 52.2% (2015) | |

| 7 | 1.48 | 2017[106] | 33.7% (2015) | |

| 8 | 1.19 | 2017[106] | 26.3% (2017)[109] | |

| 9 | 0.91 | 2017[106] | 7.2% (2015) | |

| 10 | 0.86 | 2017[106] | 5.9% (2015) | |

| 11 | 0.77 | 2015[110] | 1.9% (2015) | |

| 12 | 0.70 | 2016[111] | 11.8% (2015) | |

| 13 | 0.70 | 2016[111] | 20.8% (2015) | |

| 14 | 0.70 | 2016[111] | 17.4% (2015) | |

| 15 | 0.70 | 2016[111] | 19.4% (2015) |

Largest markets by number of box office admissions

| Rank | Country | Number of admissions (millions of tickets) | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,263 | 2016 | [112] | |

| 2 | 1,620 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 3 | 1,145 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 4 | 348 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 5 | 220 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 6 | 205 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 7 | 201 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 8 | 185 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 9 | 181 | 2017 | [113] | |

| 10 | 171 | 2017 | [113] |

See also

- Cinema by country

- List of cinema of the world

- Independent films

- Outline of film

- Television industry

Footnotes

- ↑ Matusitz, J., & Payano, P. (2011). The Bollywood in Indian and American Perceptions: A Comparative Analysis. India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs, 67(1), 65–77. doi:10.1177/097492841006700105

- 1 2 "INDIAN FEATURE FILMS CERTIFIED DURING THE YEAR 2017". Film Federation of India. 31 March 2017.

- ↑ Lang, Brent (22 March 2017). "Global Box Office Hits Record $38.6 Billion in 2016 Even as China Slows Down". Variety. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "Theatrical Market Statistics 2016" (PDF). MPAA. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Robinson, Daniel B. (2 April 2018). "The trend shift of the modern film industry" (April '18). San Fran & co. Lindale Avenue. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "European Audiovisual Observatory" (PDF) (Press release). European Audiovisual Observatory, Council of Europe. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ↑ Los Angeles Film Studies

- ↑ Donckels, William. "Disney Raises SoCal Annual Pass Prices 30% - to Keep Locals "Out"". Technorati.com. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ Number of total movies in 2014 are taken from http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?yr=2014

- ↑ "Oscar Statuette". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- ↑ Carter, David (4 November 2010). East Asian Cinema. Oldcastle Books, Limited. ISBN 9781842433805.

- ↑ "A Touch of Sin: Interview with Jia Zhang-ke". Electric Sheep. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Frater, Patrick (30 September 2015). "IMAX China Sets Cautious IPO Share Price". variety.com. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Hoad, Phil (31 December 2013). "Marvel rules, franchises dip, China thrives: 2013 global box office in review". theguardian.com. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ Brzeski, Patrick; Coonan, Clifford (3 April 2014). "Inside Johnny Depp's 'Transcendence' Trip to China". The Hollywood Reporter.

As China's box office continues to boom – it expanded 30 percent in the first quarter of 2014 and is expected to reach $4.64 billion by year's end – Beijing is replacing London and Tokyo as the most important promotional destination for Hollywood talent.

- ↑ FlorCruz, Michelle (2 April 2014). "Beijing Becomes A Top Spot On International Hollywood Promotional Tours". International Business Times.

The booming mainland Chinese movie market has focused Hollywood's attention on the Chinese audience and now makes Beijing more important on promo tours than Tokyo and Hong Kong

- ↑ "China B.O. up 27% in 2013". www.filmbiz.asia. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ "Theatrical Market Statistics 2014 - MPAA" (PDF).

- ↑ Khanna, "The Business of Hindi Films", 140

- ↑ "Annual report 2010". Central Board of Film Certification, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ↑ According to 2014 Theatrical Market Statistics by MPAA

- ↑ "Hollywood Film Revenue in India Rises 10 Percent, Boosted by Dubbed Versions". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Raja, Aditi (31 July 2012). "Film industry threatens it might have to move out of 'unsafe' Mumbai". London: Mail Online India. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ "Largest film studio". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Digital March Media & Entertainment in South India" (PDF). Deloitte. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Nigeria surpasses Hollywood as world's second largest film producer – UN". United Nations. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Brown, Funke Osae (24 December 2013). "Nollywood improves quality, leaps to N1.72trn revenue in 2013". Business Day Newspaper. Business Day Online. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Emeagwali, Gloria (Spring 2004). "Editorial: Nigerian Film Industry". Central Connecticut State University. Africa Update Vol. XI, Issue 2. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ "X-raying Nigerian Entertainment Industry At 49". Modern Ghana. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ Olubomehin, Oladipo O. (2012). "CINEMA BUSINESS IN LAGOS, NIGERIA SINCE 1903". Historical Research Letter. 3. ISSN 2224-3178.

- ↑ Ekenyerengozi, Michael Chima (21 May 2014). "Recognizing Nigeria's Earliest Movie Stars - Dawiya, King of the Sura and Yilkuba, the Witch Doctor". IndieWire. Shadow and Act. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "PALAVER: A ROMANCE OF NORTHERN NIGERIA". Colonial Film. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Lights, Camera, Africa!!!". Goethe Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ Olubomehin, Oladipo O. (2012). "CINEMA BUSINESS IN LAGOS, NIGERIA SINCE 1903". Historical Research Letter. 3. ISSN 2225-0964.

- ↑ Adegbola, Tunde (2011). "Coming of Age in Nigerian Moviemaking". African Film Festival Inc. New York. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Obiaya, Ikechukwu. "The Blossoming of the Nigerian Video Film Industry". Academia. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Olubomehin, Oladipo O. (2012). "CINEMA BUSINESS IN LAGOS, NIGERIA SINCE 1903". Historical Research Letter. 3. ISSN 2224-3178.

- ↑ "Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa". The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). "Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture". Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ ""Nollywood": What's in a Name?". Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ "Nigerian films try to move upmarket: Nollywood's new scoreboard". The Economist. The Economist. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ Kandil, Heba (2001-06-01). "The Media Free Zone: An Egyptian Media Production City Finesse - Arab Media & Society". Arab Media & Society. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ↑ Krajeski, Jenna. "Acclaimed Movie "678" Shows the Ubiquity of Sexual Harassment in Egypt". Slate.com. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ El Deeb, Sarah. "Egypt court sentences 8 to death over prophet film". Associated Press. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ Farid, Samir, "Lights, camera...retrospection" Archived 11 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Al-Ahram Weekly, 30 December 1999

- ↑ Farid, Samir, "An Egyptian Story" Archived 14 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Al-Ahram Weekly, 23–29 November 2006

- 1 2 The Iranian Cinema Archived 2 August 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ Abbas Kiarostami: Articles & Interviews

- ↑ The Iranian Cinema: A Dream With No Awakening Archived 21 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Future Korean Filmmakers Visit UCLA". Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ↑ Jameson, Sam (19 June 1989). "U.S. Films Troubled by New Sabotage in South Korea Theater". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ 한미FTA 체결, 영화산업 타격은? Archived 23 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine., MBC (Korean)

- ↑ Gorman, Patrick J. "Hong Kong to Hollywood: A "ridiculous amount of interest" in Hong Kong cinema is redefining Tinseltown". Moviemaker.com. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ "Recherche - Observatoire européen de l'audiovisuel". www.obs.coe.int. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ KANZLER, Martin (2014). The Turkish Film Industry. European Audiovisual Observatory. p. 59.

- ↑ KANZLER, Martin (2014). The Turkish Film Industry. European Audiovisual Observatory. p. 61.

- ↑ KANZLER, Martin (2014). The Turkish Film Industry. European Audiovisual Observatory. p. 67.

- ↑ KANZLER, Martin (2014). The Turkish Film Industry. European Audiovisual Observatory. p. 71.

- 1 2 KANZLER, Martin (2014). The Turkish Film Industry. European Audiovisual Observatory. p. 72.

- ↑ http://www.dawn.com/news/1045365

- ↑ an industry that once produced an average of 80 films annually was now struggling to even churn out more than two films a year.

- ↑ The Beginner's Guide to Pakistani Cinema

- ↑ "History of Bangladeshi Film". cholochitro.com. Cholochitro. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ "Mukh O Mukhosh". bfa.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Indonesia Now Home to Southeast Asia's Biggest Movie Studios". 14 November 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ "The Film Industry".

- ↑ Kissoon, Freddie (27 March 2008). "First Movie". Newsday.

- ↑ Paddington, Bruce (November 2004). "Bim, Bim, Sink or Swim". Caribbean Beat (70).

- ↑ Mendes-Franco, Janine (9 February 2014). "Bim Fans Go Online". Trinidad and Tobago Guardian.

- ↑ Pires, BC. "SistaGod Put a Hand". Trinidad and Tobago Guardian.

- ↑ "The Story of the Kelly Gang". Australian Screen, National Film and Sound Archive. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (16 September 1996). "Hooray for Bollywood!". Time Magazine.

- ↑ Pippa de Bruyn; Niloufer Venkatraman; Keith Bain (2006). Frommer's India. Frommer's. p. 579. ISBN 0-471-79434-1.

- ↑ Wasko, Janet (2003). How Hollywood works. SAGE. p. 185. ISBN 0-7619-6814-8.

- ↑ K. Jha; Subhash (2005). The Essential Guide to Bollywood. Roli Books. p. 1970. ISBN 81-7436-378-5.

- ↑ Gulzar; Nihalani, Govind; Chatterji, Saibal (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. Encyclopædia Britannica (India) Pvt Ltd. pp. 10–18. ISBN 81-7991-066-0.

- 1 2 "Decoding the Bollywood poster". National Science and Media Museum. 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Aḵẖtar, Jāvīd; Kabir, Nasreen Munni (2002). Talking Films: Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar. Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780195664621.

JA: I write dialogue in Urdu, but the action and descriptions are in English. Then an assistant transcribes the Urdu dialogue into Devnagari because most people read Hindi. But I write in Urdu. Not only me, I think most of the writers working in this so-called Hindi cinema write in Urdu: Gulzar, or Rajinder Singh Bedi or Inder Raj Anand or Rahi Masoom Raza or Vahajat Mirza, who wrote dialogue for films like Mughal-e-Azam and Gunga Jumna and Mother India. So most dialogue-writers and most song-writers are from the Urdu discipline, even today.

- ↑ "Film World". Film World. T.M. Ramachandran. 10: 65. 1974.

I feel that the Government should eradicate the age-old evil of certifying Urdu films as Hindi ones. It is a known fact that Urdu has been willingly accepted and used by the film industry. Two eminent Urdu writers Krishan Chander and Ismat Chughtai have said that "more than seventy-five per cent of films are made in Urdu." It is a pity that although Urdu is freely used in films, the producers in general mention the language of the film as "Hindi" in the application forms supplied by the Censor Board. It is a gross misrepresentation and unjust to the people who love Urdu.

- ↑ Robertson, Patrick (1988). The Guinness Book of Movie Facts & Feats (1988 ed.). London: Guinness Publishing Limited. p. 8. ISBN 0-85112-899-8.

- 1 2 Deka, Arnab Jan (27 October 1996). "Fathers of Indian Cinema Bhatawdekar and Torney". Dainik Asam (Assamese daily).

- ↑ Narwekar, Sanjit (January 1995). Marathi Cinema : In Retrospect (1995 ed.). Bombay, India: Maharashtra Film, Stage & Cultural Development Corporation Ltd. pp. 9–12.

- ↑ Rangoonwalla, Firoze (1979). A Pictorial History of Indian Cinema (1979 ed.). London, New York, Sydney, Toronto: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. p. 12. ISBN 0-600-34909-8.

- 1 2 Gulzar; Nihalani, Govind; Chatterji, Saibal (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. Encyclopædia Britannica (India) Pvt Ltd. pp. 136–137. ISBN 81-7991-066-0.

- ↑ Talking Images, 75 Years of Cinema

- ↑ K. Moti Gokulsing, K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 17. ISBN 1-85856-329-1.

- ↑ Sharpe, Jenny (2005). "Gender, Nation, and Globalization in Monsoon Wedding and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge". Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism. 6 (1): 58–81 [60 & 75]. doi:10.1353/mer.2005.0032.

- ↑ Gooptu, Sharmistha (July 2002). "Reviewed work(s): The Cinemas of India (1896–2000) by Yves Thoraval". Economic and Political Weekly. 37 (29): 3023–4.

- ↑ K. Moti Gokulsing, K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 18. ISBN 1-85856-329-1.

- ↑ Sridharan, Tarini (25 November 2012). "Mother India, not Woman India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ Bollywood Blockbusters: Mother India (Part 1) (Documentary). CNN-IBN. 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Kehr, Dave (23 August 2002). "Mother India (1957). Film in review; 'Mother India'". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ↑ Before Brando, There Was Dilip Kumar, The Quint, 11 December 2015

- ↑ "Unmatched innings". The Hindu. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ Anand (7 March 2004). "On the Bollywood beat". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ↑ Subhash K Jha (8 April 2005). "Amit Khanna: The Man who saw 'Bollywood'". Sify. Archived from the original on 9 April 2005. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- 1 2 Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (1 October 2015). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema’s Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin UK. p. 58. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ↑ "How film-maker Nasir Husain started the trend for Bollywood masala films". Hindustan Times. 30 March 2017.

- ↑ Bay, Scott (30 April 2018). "Could Artificial Intelligence Predict the Next Avengers: Infinity War?". wired.com. Wired. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ↑ Feature films - Total number of national feature films produced, UNESCO Institute for Statistics

- 1 2 "Statistics Of Film Industry In Japan". Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan, Inc. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Mexican Film Institute. (2017). Statistical yearbook of Mexican Cinema. Mexico City: Mexican Film Institute.

- ↑ "Percentage of GBO of all films feature exhibited that are national". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "New Report: Global Entertainment Market Expands on Multiple Fronts". Motion Picture Association of America. April 4, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Leading film markets worldwide in 2017, by gross box office revenue (in billions U.S. dollars)". Statista. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- 1 2 "Chinese mainland box office sees great gains in 2017, paving way for more foreign films from outside Hollywood". Global Times. 1 January 2018.

- ↑ Ramachandran, Naman (4 March 2018). "FICCI-Frames: TV Fuels Indian Creative Industry Growth, Say Studies". Variety.

- ↑ "German Box Office 2017: Revenues Rebound to $1.2 Billion". The Hollywood Reporter. January 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Canada box office revenue 2015". Statista. January 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Theatrical Market Statistics 2016 (MPAA)

- ↑ "Leading film markets worldwide by number of tickets sold 2016". Statista. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Leading film markets worldwide in 2017, by number of tickets sold (in millions)". Statista. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Allen J. Scott (2005) On Hollywood: The Place The Industry, Princeton University Press

- Robertson, Patrick (1988) The Guinness Book of Movie Facts & Feats. London: Guinness Publishing Limited

- Arnab Jan Deka (27 Oct 1996) Fathers of Indian Cinema Bhatawdekar and Torney, Dainik Asam

- Sanjit Narwekar (1995) Marathi Cinema : In Retrospect, Maharashtra Film, Stage & Cultural Development Corporation Ltd

- Firoze Rangoonwalla (1979) A Pictorial History of Indian Cinema, The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited

External links

- Movie Making Manual wikibook

- European Audiovisual Observatory

- Online Movies, Taiwanese Law, and the American Film Industry at the Wayback Machine (archived 12 March 2005) - 4 February 2002 MP3 Newswire article on the potential impact of Net distribution on the film industry

- Box Office Cinefile Review

- Doctor Strange Movie (2016) Information