Allegations of biological warfare in the Korean War

Allegations that the United States military used biological weapons in the Korean War (1950–53) were raised by the governments of People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union and North Korea. The claims were first raised in 1951. The story was covered by the worldwide press and led to a highly publicized international investigation in 1952. US Secretary of State Dean Acheson and other US and allied government officials denounced the allegations as a hoax. Subsequent scholars are split about the truth of the claims.

Background

Until the end of World War II, Japan operated a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit called Unit 731 in Harbin. The unit's activities, including human experimentation, were documented by the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials conducted by the Soviet Union in December 1949. However, at that time, the US government described the Khabarovsk trials as "vicious and unfounded propaganda".[1] It was later revealed that the accusations made against the Japanese military were correct. The US government had taken over the research at the end of the war and had then covered up the program.[2]

On 30 June 1950, soon after the outbreak of the Korean War, the US Defense Secretary George Marshall received the Report of the Committee on Chemical, Biological and Radiological Warfare and Recommendations, which advocated urgent development of a biological weapons program.[3] The biological weapons research facility at Fort Detrick in Maryland was expanded, and a new one in Pine Bluff, Arkansas was developed.[4]

Allegations

During 1951, as the war turned against the United States, the Chinese and North Koreans made vague allegations of biological warfare, but these were not pursued.[5][6] General Matthew Ridgway, United Nations Commander in Korea, denounced the initial charges as early as May 1951. He accused the communists of spreading "deliberate lies." A few days later, Vice Admiral Charles Turner Joy repeated the denials.[6]

On 28 January 1952, the Chinese People's Volunteer Army headquarters received a report of a smallpox outbreak southeast of Incheon. From February to March 1952, more bulletins reported disease outbreaks in the area of Chorwon, Pyongyang, Kimhwa and even Manchuria.[7] The Chinese soon became concerned when 13 Korean and 16 Chinese soldiers contracted cholera and the plague, while another 44 recently deceased were tested positive for meningitis.[8] Although the Chinese and the North Koreans did not know exactly how the soldiers contracted the diseases, the suspicions soon fell on the Americans.[8]

On 22 February 1952, the North Korean Foreign Ministry made a formal allegation that American planes had been dropping infected insects onto North Korea. This was immediately denied by the US government. The accusation was supported by eye-witness accounts by the Australian reporter Wilfred Burchett and others.[9][10]

In June 1952 the United States proposed to the United Nations Security Council that the Council request the International Red Cross investigate the allegations. The Soviet Union vetoed the American resolution, and, along with its allies, continued to insist on the veracity of the biological warfare accusations.[6]

In February 1953, China and North Korea produced two captured U.S. Marine Corps pilots to support the allegations. Colonel Frank H. Schwable was reported to have stated that "The basic objective was at that time to get under field conditions various elements of bacteriological warfare and possibly expand field tests at a later date into an element of regular combat operations."[6] Schwable disclosed in his press statement that B-29s flew biological warfare missions to Korea from airfields in American-occupied Okinawa starting in November 1951.[11] Other captured Americans such as Colonel Walker Mahurin made similar statements.[6]

International Scientific Commission

When the International Red Cross and the World Health Organization ruled out biological warfare, the Chinese government denounced this as Western bias and arranged an investigation by the Soviet-affiliated World Peace Council.[12] The World Peace Council set up the International Scientific Commission for the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in China and Korea. This commission included several distinguished scientists, including renowned British biochemist and sinologist Joseph Needham. The commission's findings also included eyewitnesses, and testimony from doctors as well as four American Korean War prisoners who confirmed the US use of biological warfare.[12] Its final report, which made on 15 September 1952, was that the allegation was true, that the US was indeed experimenting with biological weapons.[13]

The report suggested a link to Unit 731.[14] Former Unit 731 members Shirō Ishii, Masaji Kitano, and Ryoichi Naito, and other Japanese biological warfare experts were often named in the allegations.[6] Former members of Unit 731 were linked initially, by a Communist news agency, to a freighter that allegedly carried them and all equipment necessary to mount a biological warfare campaign to Korea in 1951.[6] The commission placed credence on allegations that Ishii made two visits to South Korea in early 1952, and another one in March 1953.[6] Chinese experts still insist today that biological warfare weapons created in an American-Japanese collaboration were used in the Korean episode.[6] Citing the claims Ishii had visited South Korea, the report stated, "Whether occupation authorities in Japan had fostered his activities, and whether the American Far Eastern Command was engaged in making use of methods essentially Japanese, were questions which could hardly have been absent from the minds of members of the Commission."[15]

The International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) publicized these claims in its 1952 "Report on U.S. Crimes in Korea",[16] as did US journalist John W. Powell.[17]

The Sams mission

The Communists also alleged that US Brigadier General Crawford Sams had carried out a secret mission behind their lines at Wonsan in March 1951, testing biological weapons.[18] The US government said that he had actually been investigating a reported outbreak of bubonic plague in North Korea, but had determined it was hemorrhagic smallpox. Sams' mission had been launched from the US navy's LCI(L)-1091, which had been converted to a Laboratory Ship in 1951.[19] During her time in Korea, the ship was assigned as an Epidemiological Control Ship[20] for Fleet Epidemic Disease Control Unit No. 1, a part of the U.S. effort to combat malaria in Korea.[21] After covert missions in North Korea, from October to September 1951, LSIL-1091 was at Koje-do testing residents and refugees for malaria.[22]

Counterclaims

The US and its allies responded by describing the allegations as a hoax.[23] The US government declared IADL to be a Communist front organization since 1950, and charged Powell with sedition.[17][24][25] Upon release the prisoners of war repudiated their confessions which they said had been extracted by torture.[26] The American authorities also have continually denied the charges of postwar Japanese-United States cooperation in biological warfare developments.[6]

An Australian colleague, Denis Warner, went so far as to suggest that the story had been concocted by Wilfred Burchett as part of his alleged role as a KGB agent of influence. Warner pointed out the similarity of the allegations to a science fiction story by Jack London, a favorite author of Burchett's.[27] However, the notion that Burchett originated the "hoax" has been decisively refuted by one of his most trenchant critics, Tibor Méray.[28]

Méray worked as a correspondent for Hungary during the war but fled the country after the abortive uprising of 1956. Now a staunch anti-Communist, he has confirmed that he saw clusters of flies crawling on ice.[29] Méray has argued the evidence was the result of an elaborate conspiracy: "Now somehow or other these flies must have been brought there... the work must have been carried out by a large network covering the whole of North Korea."[30]

Disease prevention measures

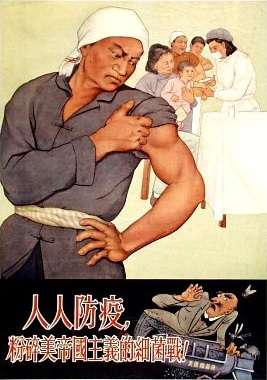

Recent research has indicated that, regardless of the accuracy of the allegations, the Chinese acted as if they were true.[7] After learning of the outbreaks, Mao Zedong immediately requested Soviet assistance on disease preventions, while the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Logistics Department was mobilized for anti-bacteriological warfare.[31] On the Korean battlefield, four anti-bacteriological warfare research centers were soon set up, while about 5.8 million doses of vaccine and 200,000 gas masks were delivered to the front.[32] Within China, 66 quarantine stations were also set up along the Chinese borders, while about 5 million Chinese in Manchuria were inoculated.[31] The Chinese government also initiated the "Patriotic Health and Epidemic Prevention Campaign" and directed every citizen to kill flies, mosquitoes and fleas.[31] These disease prevention measures soon resulted in an improvement of health for Communist soldiers on the Korean battlefield.[32] Tibor Méray provided eyewitness account of North Korea conducting an "unprecedented campaign of public health" during the allegation.[33]

Subsequent evaluation

Subsequent historians have offered other explanations to the disease outbreaks during the spring of 1952. For example, it has been noted that spring time is usually a period of epidemics within China and North Korea,[31] and years of warfare had also caused a breakdown in the Korean health care system. Historians have argued that under these circumstances, diseases could easily spread throughout the entire military and civilian populations within Korea.[34][35]

Australian historian Gavan McCormack argued that the claim of US biological warfare use was "far from inherently implausible", pointing out that one of the POWs who confessed, Walker Mahurin, was in fact associated with Fort Detrick.[36] He also pointed out that, as the deployment of nuclear and chemical weapons was considered, there is no reason to believe that ethical principles would have overruled the resort to biological warfare.[37] He also suggested that the outbreak in 1951 of viral haemorrhagic fever, which had previously been unknown in Korea, was linked to biological warfare.[38] A 1988 book on the Korean War, by historians Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, also suggested the claims might be true.[39][40] In 1989, a British study of Unit 731 strongly supported the theory of United States–Japanese biological warfare culpability in Korea.[6] The official Chinese government stance in the mid-1990s was that biological warfare was a real threat at the time and they reacted properly in order to prevent serious epidemics from spreading throughout North Korea and China.[41]

In 1995 and with access to newly available Chinese documents, historian Shu Guang Zhang noted that there is little, if any information that currently exists on the Chinese side which explains how the Chinese scientists came up with the conclusion of US biological warfare during the disease outbreak in the spring of 1952. Zhang further theorized that the allegation was caused by unfounded rumors and scientific investigations on the allegation was purposely ignored on the Chinese side for the sake of domestic and international propaganda.[41]

In 1998, Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagermann claimed that the accusations were true in their book, The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea.[42] The book received mixed reviews; out of 20 reviews cited, 2 reviews were negative, with a U.S. military academy professor calling the book an example of "bad history"[43] and with another review calling the book's lack of direct evidence "appalling",[44] although neither of these two negative reviews considers either the admissions that the U.S. deployed chemical and biological weapons by Colonels Schwable and Mahurin, or the U.S. chemical and biological weapons caches at locations such as Camp Detrick and elsewhere or even the extensive documented history of clandestine drug tests undertaken among the U.S. population itself (cited in sources such as biographies of Frank Olson). Eighteen other reviews praised the case the authors made.[43] In response, Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg of the Cold War International History Project at the Woodrow Wilson Center released a cache of Soviet and Chinese documents in 1998 showing the North Korean claim to have been an elaborate disinformation campaign.[45] They revealed that North Korea's health minister traveled in 1952 to the remote Manchurian city of Mukden where he procured a culture of plague bacilli which was used to infect condemned criminals as part of an elaborate disinformation scheme. Tissue samples were then used to fool the international investigators. The papers included telegrams and reports of meetings among Soviet and Chinese leaders, including Chairman Mao Zedong. A report to Lavrenti Beria, head of Soviet intelligence, for example, stated: "False plague regions were created, burials... were organized, measures were taken to receive the plague and cholera bacillus." These documents revealed that only after Stalin's death the following year did the Soviet Union halt the disinformation campaign.[46] Weathersby and Leitenberg consider their evidence to be conclusive—that the allegations were disinformation and no biological warfare use occurred.[47][48][49] In 2001, KGB expert Herbert Romerstein supported Weathersby and Leitenberg's position while criticizing Endicott's research on the basis that it is purely based on accounts provided by the Chinese government.[50]

Published in Japan in 2001, the book Rikugun Noborito Kenkyujo no shinjitsu or The Truth About the Army Noborito Institute revealed that members of Japan's Unit 731 also worked for the "chemical section" of a U.S. clandestine unit hidden within Yokosuka Naval Base during the Korean War as well as on projects inside the United States from 1955 to 1959.[51]

According to Jeff Kaye's interpretation of a "Memorandum of Conversation" from the Psychological Strategy Board (PSB) dated July 6, 1953 (and declassified and released by the CIA in 2006),[52] the U.S. protestations at the United Nations did not mean the U.S. was serious about conducting any investigation into biological warfare charges, despite what the government said publicly. The reason the U.S. didn't want any investigation was because an "actual investigation" would reveal military operations, "which, if revealed, could do us psychological as well as military damage." The memorandum, which had been sent to CIA director Allen Dulles, specifically stated as an example of what could be revealed "Eighth Army preparations or operations (e.g. chemical warfare)."[53]

Author Simon Winchester concluded in 2008 that Soviet intelligence was sceptical of the allegation, but that North Korea leader Kim Il Sung believed it.[54] Winchester said the question "has still not been satisfactorily answered".[55]

In accounts published in 2013, after his death, Wu Zhili, the former Surgeon General of Chinese People's Voluntary Army, said that the Chinese allegation was a false alarm, and that he had been forced to fabricate evidence.[56][57]

According to Australian author and judge, Michael Pembroke, the documents associated with Beria were mostly created during the time of the power struggle after Stalin's death and are therefore questionable.[58] He concludes that, "It seems likely that the full story of the United States' involvement in biological warfare in Korea has not yet been told."[59]

See also

Further reading

- Shiwei Chen, "History of Three Mobilizations: A Reexamination of the Chinese Biological Warfare Allegations against the United States in the Korean War," Journal of American-East Asian Relations 16.3 (2009): 213-247.

- John Clews, The Communists. New Weapon: Germ Warfare (London, 1952)

- Stephen L. Endicott, "Germ Warfare and "Plausible Denial": The Korean War, 1952–1953," Modern China 5.1 (Jan. 1979): 79-104.

- Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman, The United States and Biological Warfare (Bloomington, Ind., 1998)

- Report of the International Scientific Commission for the Investigation of the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in Korea and China (Peking and Prague, 1952);

- Stanley I. Kutler, The American Inquisition: Justice and Injustice in the Cold War (New York, 1982)

- Albert E. Cowdrey, "Germ Warfare. and Public Health in the Korean Conflict," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 39 (1984)

- John Ellis van Courtland Moon, "Biological Warfare Allegations: The Korean War Case," Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 666 (1992)

- Tom Buchanan, "The Courage of Galileo: Joseph Needham and the .Germ Warfare. Allegations in the Korean War," History 86 (October 2001)

- Julian Ryall, "Did the US wage germ warfare in Korea?", Telegraph, (June 10, 2010).

- Ruth Rogaski, "Nature, Annihilation, and Modernity: China's Korean War Germ-Warfare Experience Reconsidered," Journal of Asian Studies 61 (May 2002)

- Nianqun Yang, "Disease Prevention, Social Mobilization and Spatial Politics: The Anti Germ-Warfare Incident of 1952 and the Patriotic Health Campaign," Chinese Historical Review 11 (Fall 2004).

References

- ↑ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. p. 116.

- ↑ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Pembroke, Michael (2018). Korea: Where the American Century Began. Hardie Grant Books. pp. 174, 292.

- ↑ Pembroke, Michael (2018). Korea: Where the American Century Began. Hardie Grant Books. p. 174.

- ↑ Simon Winchester, The Man who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom, Harper Collins, New York, 2008, pp 199–200; Gavan McCormack, "Korea: Wilfred Burchett's Thirty Year's War", in Ben Kiernan (ed.), Burchett: Reporting the Other Side of the World, 1939-1983, Quartet Books, London, 1986, pp 202-203.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sheldon H. Harris (3 May 2002). Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-45, and the American Cover-up. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-43536-6

- 1 2 Zhang, Shu Guang (1995), Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950-1953, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, p. 181, ISBN 0-7006-0723-4

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 182.

- ↑ Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Kosovo, (revised edition), Prion, London, 2000, p 388.

- ↑ 李, 玮 (April 4, 2010). 抗美援朝-反细菌战 (in Chinese). 宁夏网. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ Schwable, Colonel Frank H.; Thomas, Kenn (December 6, 1952). "Of Bugs and Bombs". Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- 1 2 Guillemin, Jeanne. Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism, (Google Books), Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 99–105, ( ISBN 0-231-12942-4).

- ↑ Simon Winchester, The Man who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom, Harper Collins, New York, 2008, pp 203-208.

- ↑ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. p. 116.

- ↑ [Report of the International Scientific Commission for the Investigation of the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in Korea and China (Peking and Prague, 1952), p. 14]

- ↑ "Report on U.S. Crimes in Korea" (PDF). International Association of Democratic Lawyers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- 1 2 "John W. Powell Dies at 89; Journalist was Tried on Sedition Charges in 1950s". LA Times. December 23, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ Sonia G Benson, Korean War: Almanac and Primary Sources, Gale, New York, 2003, p 182.

- ↑ FEDCU One Fight an Unseen Enemy

- ↑ "HISTORY OF NAVY ENTOMOLOGY". United States Navy Medical Entomology. United States Navy. 2006-05-03. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ↑ Marshall, Irvine H. (1955). "Malaria in Korea". In Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Recent advances in medicine and surgery (19–30 April 1954) based on professional medical experiences in Japan and Korea, 1950-1953. Washington: Walter Reed Army Medical Center. p. 282. OCLC 4011756. Retrieved 2007-12-11. (See footnote 5.)

- ↑ Marshall, p. 272.

- ↑ Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Kosovo, (revised edition), Prion, London, 2000, p 388.

- ↑ "Report on the National Lawyers Guild, legal bulwark of the Communist Party". United States Congress House Committee on Un-American Activities. September 17, 1950.

The current international Communist front for attorneys is known as the International Association of Democratic Lawyers. This organization is sometimes referred to as the International Association of Democratic Jurists.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Bulletin (PDF) (Report). Central Intelligence Agency. October 4, 1958. p. 5. CIA-RDP79T00975A004000200001.

pro-communist International Association of Democratic Lawyers

- ↑ Lech, Raymond B. (2000), Broken Soldiers, Chicago, IL: University of Illinois, pp. 162&ndash, 163, ISBN 0-252-02541-5

- ↑ Denis Warner, Not Always on Horseback: An Australian Correspondent at War and Peace in Asia, 1961-1993, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards, 1997, pp 196-197.

- ↑ Tibor Méray, On Burchett, Callistemon Publications, Kallista, Victoria, Australia, 2008, pp 73-76.

- ↑ Tibor Méray, On Burchett, Callistemon Publications, Kallista, Victoria, Australia, 2008, p 51.

- ↑ Tibor Méray, On Burchett, Callistemon Publications, Kallista, Victoria, Australia, 2008, p 252.

- 1 2 3 4 Zhang 1995, p. 184.

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 185.

- ↑ Tibor Méray, On Burchett, Callistemon Publications, Kallista, Victoria, Australia, 2008, pp 261-262.

- ↑ Eitzen, Edward M.; Takafuji, Ernest T. "Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare" (PDF). United States Government Printing. p. 419. ISBN 9997320913.

- ↑ Lech 2000, p. 162.

- ↑ Gavan McCormack, "Korea: Wilfred Burchett's Thirty Year's War", in Ben Kiernan (ed.), Burchett: Reporting the Other Side of the World, 1939-1983, Quartet Books, London, 1986, p 204.

- ↑ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. p. 118.

- ↑ Auster, Bruce B. "Unmasking an Old Lie Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine.", U.S. News and World Report, November 16, 1998. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ↑ Korea: The Unknown War (Viking, 1988)

- 1 2 Zhang 1995, p. 186.

- ↑ Endicott, Stephen, and Hagermann, Edward. The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea, (Google Books, relevant excerpt), Indiana University Press, 1998, pp. 75-77, ( ISBN 0-253-33472-1), links accessed January 7, 2009.

- 1 2 "Reviews of The United States and Biological Warfare: secrets of the Early Cold War and Korea", York University, compiled book review excerpts. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ↑ Regis, Ed. "Wartime Lies?", The New York Times, June 27, 1999. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ↑ Weathersby, Kathryn, & Milton Leitenberg, "New Evidence on the Korean War", Cold War International History Project, 1998. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ↑ Auster, Bruce B. "Unmasking an Old Lie" Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine., U.S. News and World Report, November 16, 1998. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ↑ Leitenberg , Milton (1998), The Korean War Biological Warfare Allegations Resolved. Occasional Paper 36. Stockholm: Center for Pacific Asia Studies at Stockholm University (May issue).

- ↑ Leitenberg , Milton (1998), "New Russian Evidence on the Korean Biological Warfare Allegations: Background and Analysis"; Woodrow Wilson Center Cold War International History Project, Bulletin 11 (Winter issue), pp 185-199.

- ↑ Weathersby, Kathryn (1998), "Deceiving the Deceivers: Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang, and the Allegations of Biological Weapons Use in Korea", Woodrow Wilson Center Cold War International History Project, Bulletin 11 (Winter issue), pp 176-185.

- ↑ Herbert Romerstein (2001). "Disinformation as a KGB Weapon in the Cold War". The Journal of Intelligence History. International Intelligence History Association. 1: 59.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency review of "Rikugun Noborito Kenkyujo no shinjitsu (The Truth About the Army Noborito Research Institute)" By Shigeo Ban. Tokyo: Fuyo Shobo Shuppan, 2001

- ↑ Exploitation of Communist BW Charges (PDF) (Report). Central Intelligence Agency. 7 July 1953. CIA-RDP80R01731R003300190004-6. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Kaye, Jeff (December 10, 2013). "CIA Document Suggests U.S. Lied About Biological, Chemical Weapon Use in the Korean War". The Dissenter. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Simon Winchester, The Man who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom, Harper Collins, New York, 2008, pp 212-214.

- ↑ Winchester 2008, p 199.

- ↑ Wu, Zhili (吴之理) (2014-01-01), Why did Zhou Enlai Stopped the Biological Warfare Allegation Campaign: Because the Chinese People's Voluntary Army Headquarters Admitted Manipulating Facts (周恩来为何不让再批美军细菌战:志司承认做了手脚) (in Chinese), Hong Kong: Phoenix Television, retrieved 2014-01-31

- ↑ Wu, Zhili (吴之理) (2013-10-01). "The Germ War of 1952 Was a False Alarm (52年的细菌战是一场虚惊)". Yan Huang Historical Review (炎黄春秋) (in Chinese) (11).

- ↑ Pembroke, Michael (2018). Korea: Where the American Century Began. Hardie Grant Books. p. 177.

- ↑ Pembroke, Michael (2018). Korea: Where the American Century Began. Hardie Grant Books. p. 182.