Korean pottery and porcelain

.jpg)

Korean ceramic history begins with the oldest earthenware dating to around 8000 BC. Influenced by Chinese ceramics, Korean pottery developed a distinct style of its own, with its own shapes, such as the moon jar or maebyeong version of the Chinese meiping vase, and later styles of painted decoration. Korean ceramic trends had an influence on Japanese pottery and porcelain.[1] Examples of classic Korean wares are the celadons of the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) and the white porcelains of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897).

History

Neolithic

The earliest known Korean pottery dates back to around 8000 BC,[2] and evidence of Mesolithic Pit–Comb Ware culture (or Yunggimun pottery) is found throughout the peninsula, such as in Jeju Island. Jeulmun pottery, or "comb-pattern pottery", is found after 7000 BC, and is concentrated at sites in west-central regions of the Korean Peninsula, where a number of prehistoric settlements, such as Amsa-dong, existed. Jeulmun pottery bears basic design and form similarities to that of Mongolia, the Amur and Sungari river basins of Manchuria, the Jōmon culture in Japan, and the Baiyue in Southern China and Southeast Asia.[3][4]

Later Silla

Pottery of the Later Silla period (668–935) was initially simple in color, shape, and design. Celadon subsequently became the main production.

Buddhism, the dominant religion of the time in Korea, increased the demand for celadon-glazed wares (cheongja), causing cheongja celadon to evolve very quickly, with more organic shapes and decorations, such as animal and bird motifs. When making cheongja wares, a small amount of iron powder was added to the refined clay, which was then coated with a glaze and an additional small amount of iron powder, and then finally fired. This allowed the glaze to be more durable, with a shinier and glossier finish than white wares.

Goryeo

The Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) achieved the unification of the Later Three Kingdoms under Wang Geon. The works of this period are generally considered to be the finest works of ceramics in Korean history.[5][6][7] Korean celadon reached its pinnacle with the invention of the sanggam inlay technique in the early 12th century.[8][9][10]

Key-fret, foliate designs, geometric or scrolling flowerhead bands, elliptical panels, stylized fish,insects,birds and the use of incised designs began at this time. Glazes were usually various shades of celadon, with browned glazes to almost black glazes being used for stoneware and storage. Celadon glazes could be rendered almost transparent to show black and white inlays. Jinsa "underglaze red", a technique using copper oxide pigment to create copper-red designs, was developed in Korea during the 12th century, and later inspired the "underglaze red" ceramics of the Yuan dynasty.[11][12][13][14]

While the forms generally seen are broad-shouldered jars, larger low jars or shallow smaller jars, highly decorated celadon cosmetic boxes, and small slip-inlaid cups, the Buddhist potteries also produced melon-shaped vases, chrysanthemum cups often of spectacularly architectural design on stands with lotus motifs and lotus flower heads. In-curving rimmed alms bowls have also been discovered similar to Korean metalware. Wine cups often had a tall foot which rested on dish-shaped stands.

Baekja wares came from highly refined white clay, glazed with feldspar, and fired in regulated and clean large kilns. Despite the refining process, white glazes invariably vary as a result of the properties of the clay itself; firing methods were not uniform, temperatures varied and glazes on pieces vary from pure white, in an almost snowy thickness, through milky white that shows the clay beneath deliberately in washed glaze, to light blue and light yellow patinas. After having succeeded the tradition of Goryeo baekja, soft white porcelain was produced in Joseon Dynasty, that carried on, but from the mid-Joseon on hard white porcelain became the mainstream porcelain.[15][16]

The baekja wares reached their zenith immediately before the Joseon Dynasty came to power. Fine pieces have recently been found in the area around Wolchil Peak near Mount Kumgang. The transitional wares of white became expressions of the Joseon Dynasty celebrations of victory in many pieces decorated with Korean calligraphy. Traditionally white wares were used by both the scholarly Confucian class, the nobility and royalty on more formal occasions.

Joseon

During the Joseon dynasty, (1392–1897) ceramic wares were considered to represent the highest quality of achievement from royal, city, and provincial kilns, the last of which were export-driven wares. Joseon enjoyed a long period of growth in royal and provincial kilns, and much work of the highest quality still preserved.

Wares evolved along Chinese lines in terms of colour, shape, and technique. Celadon, white porcelain, and storage pottery were similar, but with certain variations in glazes, incision designs, florality, and weight. The Ming influence in blue and white wares using cobalt-blue glazes existed, but without the pthalo blue range, and the three-dimensional glassine colour depth of Ming Dynasty Chinese works.

Simplified designs emerged early on. Buddhist designs still prevailed in celadon wares: lotus flowers, and willow trees. The form most often seen was that of pear-shaped bottles. Notable were thinner glazes, and colourless glazes for buncheong or stoneware. During the Joseon period, Koreans applied the sanggam tradition to create buncheong ceramics.[17][18] In contrast to the refined elegance of Goryeo celadon, buncheong is designed to be natural, unassuming, and practical.[19] However, the buncheong tradition was gradually replaced by Joseon white porcelain, its aristocratic counterpart, and disappeared in Korea by the end of the 16th century.[18] Buncheong became known and prized in Japan as Mishima.[20][21][22]

Joseon white porcelain representing Joseon ceramics was produced throughout the entire period of the Joseon dynasty. The plain and austere white porcelain suitably reflects the taste of Neo-Confucian scholars.[23] Qing colouring, brighter and almost Scythian in enamel imitation, was rejected by Korean potters, in favour of simpler, less decorated wares in keeping with a new dynasty that built itself on Confucian doctrine.

Generally, the ceramics of this dynasty is divided into early, middle, and late periods, changing every two centuries, approximately; thus 1300 to 1500 is the early period, 1500 to 1700 the middle, and 1700 to 1900–1910 the late period.

The wares began to assume more traditional Korean glazes and more specific designs to meet regional needs. This is to be expected, as the Scythian art influences were of the former dynasty. The rise of white porcelain occurred as a result of Confucian influence and ideals, resulting in purer, less pretentious forms lacking artifice and complexity.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| History |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

|

Monuments |

|

National symbols of Korea |

|

In 1592 during the Japanese invasion of Korea, entire villages of Korean potters were forcibly relocated to Japan, damaging the pottery industry as craftsmen had to relearn techniques because the masters were gone.[24]

Exports

Nearly all exports of Korean ceramics went to Japan, and most were from provincial coastal kilns, especially in the Busan area. Export occurred in two ways: either through trading or through invasion and theft of pottery and the abduction[25] to Japan of families of potters who made the wares. The voluntary immigration of potters was improbable since Joseon pottery was administrated by the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (工曹) (ko:공조 (행정기관)). As a national resource, pottery technician trade with foreign countries was prohibited.

Kilns

Central to Korean success were the chambered climbing kilns, based on the Chinese dragon kiln, that were used throughout the Joseon dynasty and exported abroad, especially to Japan by Korean kiln-makers where they were renamed as noborigama in the Karatsu area from the 17th century on.

Modern kilns are either electric or gas-fired.

Centers for studying Korean ceramics

- Department of Ceramics at the College of Art and Design, Ewha Womans University in Seoul

- Department of Ceramics at the College of Art and Design, Kongju National University in Gongju

- Korea Ceramic Foundation (KOCEF)

Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Korean pottery. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Goryeo_celadon. |

Sheep-shaped celadon from the 3rd to 4th century Baekje

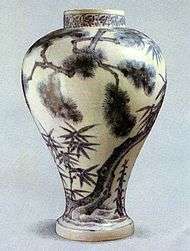

Sheep-shaped celadon from the 3rd to 4th century Baekje "Cheongja unhak sanggam mun maebyeong", adorned with drawings of the red cranes. 12th-century.

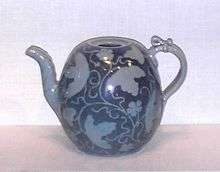

"Cheongja unhak sanggam mun maebyeong", adorned with drawings of the red cranes. 12th-century..jpg) Wine ewer, Goryeo Dynasty, c. 1250 AD

Wine ewer, Goryeo Dynasty, c. 1250 AD Goryeo-era Celadon exhibited at National Museum of Korea

Goryeo-era Celadon exhibited at National Museum of Korea White porcelain bowl, Joseon dynasty, 15th century AD

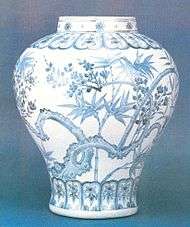

White porcelain bowl, Joseon dynasty, 15th century AD Blue & white porcelain jar, Joseon dynasty, 15th century AD

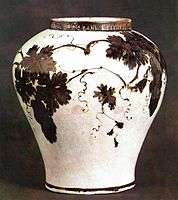

Blue & white porcelain jar, Joseon dynasty, 15th century AD Joseon porcelain pot to draw pattern of grapes and monkey with Iron oxide, Joseon dynasty, early 18th century AD

Joseon porcelain pot to draw pattern of grapes and monkey with Iron oxide, Joseon dynasty, early 18th century AD Blue & white porcelain bottle, 19th century AD

Blue & white porcelain bottle, 19th century AD

See also

Notes

- ↑ Koehler, Robert (2015). Korean Ceramics: The Beauty of Natural Forms. Seoul Selection. ISBN 9781624120466. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Chong Pil Choe, Martin T. Bale, "Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea", (2002), Arctic Anthropology, 39: 1-2, pp. 95-121.

- ↑ Stark 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ Lee Hyun-hee 2005, pp. 23–26.

- ↑ "Koreana : a Quarterly on Korean Art & Culture".

- ↑ "Korean-Arts About Korean Celadon".

- ↑ Francoeur, Susanne (1 January 2004). "Review of Goryeo Dynasty: Korea's Age of Enlightenment, 918-1392". The Journal of Asian Studies. 63 (4): 1154–1156. doi:10.2307/4133247 (inactive 2018-08-13). JSTOR 4133247.

- ↑ Koehler, Robert (2015-09-07). Korean Ceramics: The Beauty of Natural Forms. Seoul Selection. ISBN 9781624120466. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ Lee, Soyoung. "Goryeo Celadon". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014-12-15). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781107098466. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ Lee, Lena Kim (1981). Korean Art. Philip Jaisohn Memorial Foundation. p. 15. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

Koryo potters also experimented with the use of copper for red designs under the glaze, since ground copper pigment fires red in the reducing kiln atmosphere. This technique was started in the twelfth century. Many scholars agree that Chinese Yuan wares with underglaze red design were inspired by the Koryo potters' use of copper red at the time when the Yuan and Koryo courts had very close political ties.

- ↑ "Collection online". British Museum. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Sullivan, Michael (1984). The Arts of China. University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 9780520049185. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ "진사 이야기". The Yonsei Chunchu (in Korean). Yonsei University. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Yunesŭkʻo Hanʾguk Wiwŏnhoe. Unesco Korean survey. Dong-a Pub. Co., 1960. p.32

- ↑ Pictorial Korea. Korean Overseas Information Service, 2004. p.28

- ↑ Koehler, Robert (2015-09-07). Korean Ceramics: The Beauty of Natural Forms. Seoul Selection. ISBN 9781624120466. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- 1 2 Lee, Author: Soyoung. "Joseon Buncheong Ware: Between Celadon and Porcelain". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Koehler, Robert (2015-09-07). Korean Ceramics: The Beauty of Natural Forms. Seoul Selection. ISBN 9781624120466. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Levenson, Jay A.; (U.S.), National Gallery of Art (1991). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Yale University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0300051674. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Hopper, Robin (2004-10-29). Making Marks: Discovering the Ceramic Surface. Krause Publications Craft. p. 103. ISBN 978-0873495042. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. Encyclopedia of Kitchen History. Routledge. p. 764. ISBN 9781135455729. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Scott Hudson, National Museum of Korea, Sol Publishing, 2005

- ↑ "History of South Korea". Lonely Planet Travel Information.

- ↑ Financial Times - Korea’s artistic treasures – and their links to China and Japan by David Pilling APRIL 11, 2014

References

- Arts of Korea. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1998. ISBN 978-0870998508.

- Goro Akaboshi, Five Centuries of Korean Ceramics, Weatherhill, 1975.

- Lee, Hong-yung; Ha, Yong-Chool; Sorensen, Clark W., eds. (2013). Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 1910-1945. U of Washington Press. ISBN 9780-2959-9216-7.

- Stark, Miriam T. (2005). Archaeology Of Asia. Boston: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-0212-4.

External links

- The Asian Art Museum, An excellent Korean ceramics collection

- The Art of Korean Potters Exhibit

- Korean History

- Over 120 pictures of Korean Pottery from the Freer Gallery

- Koryo dynasty

- Korean ceramics Details of an exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution

- Comprehensive Archaeological Bibliography of Korean Pottery

- Talks on the Korean impact on Japanese ceramics (Archived 2009-10-31)

- Joseon Dragon vase (Archived 2009-10-31) with softer watery-blue glaze and naturalistic brush-strokes

- From the Fire: Contemporary Korean ceramics International Arts Ceramic Artists exhibition

- Mountain Dreams: Contemporary Ceramics by Yoon Kwang-cho — Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition

- Reviving the Korean Ceramics Tradition at the American Museum of Ceramic Art

.jpg)