Local government in England

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of England |

|

|

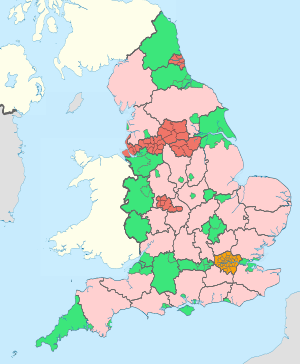

The pattern of local government in England is complex, with the distribution of functions varying according to the local arrangements.

Legislation concerning local government in England is decided by the Parliament and Government of the United Kingdom, because England does not have a devolved parliament or regional assemblies, outside Greater London.

Structure

Regional authorities and Combined authorities

England has, since 1994 been subdivided into nine regions. One of these, London, has an elected Assembly and Mayor. The other regions no longer have any statutory bodies to execute any responsibilities.

Combined authorities were introduced in England outside Greater London by the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 to cover areas larger than the existing local authorities but smaller than the regions. Combined authorities are created voluntarily and allow a group of local authorities to pool appropriate responsibility and receive certain delegated functions from central government in order to deliver transport and economic policy more effectively over a wider area. There are currently nine such authorities, with the Greater Manchester Combined Authority established on 1 April 2011, Liverpool City Region Combined Authority and three others in April 2014, two in 2016 and two in 2017.

Principal councils

Below the region level and excluding London, England has two different patterns of local government in use. In some areas there is a county council responsible for services such as education, waste management and strategic planning within a county, with several non-metropolitan district councils responsible for services such as housing, waste collection and local planning. Both are principal councils and are elected in separate elections.

Some areas have only one level of local government. These are unitary authorities, which are also principal councils. Most of Greater London is governed by London borough councils. The City of London and the Isles of Scilly are sui generis authorities, pre-dating recent reforms of local government.

There are 125 'single tier' authorities, which all function as billing authorities for Council Tax and local education authorities:

- 55 unitary authorities

- 36 metropolitan boroughs

- 32 London boroughs

- The Common Council of the City of London

- The Council of the Isles of Scilly

There are 33 'upper tier' authorities. The non-metropolitan counties function as local education authorities:

- 27 non-metropolitan counties

- 6 metropolitan counties (councils abolished in 1986)

There are 201 'lower tier' authorities, which all have the function of billing authority for Council Tax:

There are in total 353 principal councils[1], not including the Corporation of London, the Council of the Isles of Scilly, or the Inner Temple and Middle Temple, the last two of which are also local authorities for some purposes.

Parishes

Below the district level, a district may be divided into several civil parishes. Typical activities undertaken by a parish council include allotments, parks, public clocks, and entering Britain in Bloom. They also have a consultative role in planning. Councils such as districts, counties and unitaries are known as principal local authorities in order to differentiate them in their legal status from parish and town councils, which are not uniform in their existence. Local councils tend not to exist in metropolitan areas but there is nothing to stop their establishment. For example, Birmingham has a parish, New Frankley. Parishes have not existed in Greater London since 1965, but from 2007 they could legally be created. In some districts, the rural area is parished and the urban is not — such as the Borough of Hinckley and Bosworth, where the town of Hinckley is unparished and has no local councils, while the countryside around the town is parished.[2] In others, there is a more complex mixture, as in the case of the Borough of Kettering, where the small towns of Burton Latimer, Desborough and Rothwell are parished, while Kettering town itself is not. In addition, among the rural parishes, two share a joint parish council and two have no council but are governed by an annual parish meeting.[3]

History

The current arrangement of local government in England is the result of a range of incremental measures which have their origins in the municipal reform of the 19th century. During the 20th century, the structure of local government was reformed and rationalised, with local government areas becoming fewer and larger, and the functions of local councils amended. The way local authorities are funded has also been subject to periodic and significant reform.

People

Councillors and mayors

Councils have historically had no split between executive and legislature. Functions are vested in the council itself, and then exercised usually by committees or subcommittees of the council.

The chairman of the council itself has authority to conduct the business of meetings of the full council, including the selection of the agenda, but otherwise the chairmanship is considered an honorary position with no real power outside the council meeting. The chairman of a borough has the title 'Mayor'. In certain cities the mayor is known as the Lord Mayor; this is an honour which must be granted by Letters Patent from the Crown. The chairman of a town council too is styled the 'town mayor'. Boroughs are in many cases descendants of municipal boroughs set up hundreds of years ago, and so have a number of traditions and ceremonial functions attached to the mayor's office.[4] Where a council would have both civic mayor, namely the chairman of the council, and an executive mayor, it has become usual for the chairman to take the take the simple title 'Chairman' or 'Chair'.[5]

The post of Leader of the Council has been recognised. Leaders typically chair several important committees, and receive a higher allowance to reflect their additional responsibilities, but they have no special, legal authority.

Under section 15 the Local Government and Housing Act 1989, committees must roughly reflect the political party makeup of the council; before it was permitted for a party with control of the council to 'pack' committees with their own members. This pattern was based on that established for municipal boroughs by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, and then later adopted for county councils and rural districts.

In 2000, Parliament passed the Local Government Act 2000 requiring councils to move to an executive-based system, either with the council leader and a cabinet acting as an executive authority, or with a directly elected mayor — with either having a cabinet drawn from the councillors — or a mayor and council manager. There was a small exception to this whereby smaller district councils (population of less than 85,000) can adopt a modified committee system. Most councils used the council leader and cabinet option, while 52 smaller councils were allowed to propose alternative arrangements based on the older system (Section 31 of the Act), and Brighton and Hove invoked a similar provision (Section 27(2)(b)) when a referendum to move to a directly elected mayor was defeated. In 2012, principal councils began returning to Committee systems, under the Localism Act 2011.

There are now 16 directly elected mayors, in districts where a referendum was in favour of them. Several of the mayors originally elected were independents (notably in Tower Hamlets and Middlesbrough, which in parliamentary elections are usually Labour Party strongholds). Since May 2002, only a handful of referendums have been held, and they have mostly been negative, with only a few exceptions. The decision to have directly elected mayors in Hartlepool and Stoke-on-Trent were subsequently reversed when further referendums were held.

The executive where it exists, in whichever form, is held to account by the remainder of the councillors acting as the "Overview and Scrutiny function" — calling the Executive to account for their actions and to justify their future plans. In a related development, the Health and Social Care Act 2001, Police and Justice Act 2006, and 2006 local government white paper set out a role for local government Overview and Scrutiny in creating greater local accountability for a range of public-sector organisations. Committee system councils have no direct 'scrutiny' role, with the decisions being scrutinised as they are taken by the committee, and potentially referred to full council for review.

Councils may make people honorary freemen or honorary aldermen. A mayor's term of office lasts for the municipal year.

Elections

The area which a council covers is divided into one or more electoral divisions – known in district and parish councils as "wards", and in county councils as "electoral divisions". Each ward can return one or more members; multi-member wards are quite common. There is no requirement for the size of wards to be the same within a district, so one ward can return one member and another ward can return two. Metropolitan borough wards must return a multiple of three councillors, while until the Local Government Act 2003 multiple-member county electoral divisions were forbidden.

In the election, the candidates to receive the most votes win, in a system known as the multi-member plurality system. There is no element of proportional representation, so if four candidates from the Mauve Party poll 2,000 votes each, and four candidates from the Taupe Party poll 1,750 votes each, all four Mauve candidates will be returned, and no Taupe candidates will. This has been said by some to be undemocratic.[6]

The term of a councillor is usually four years. Councils may be elected wholly, every four years, or 'by thirds', where a third of the councillors get elected each year, with one year with no elections. Recently, the 'by halves' system, whereby half of the council is elected every two years, has been allowed. Sometimes wholesale boundary revisions will mean the entire council will be re-elected, before returning to the previous elections by thirds or by halves over the coming years. Recent legislation allows a council to move from elections by thirds to all-up elections.

Often, local government elections are watched closely to detect the mood of the electorate before upcoming parliamentary elections.

Officers

Councillors cannot do the work of the council themselves, and so are responsible for appointment and oversight of officers, who are delegated to perform most tasks. Local authorities nowadays may appoint a 'Chief Executive Officer', with overall responsibility for council employees, and who operates in conjunction with department heads. The Chief Executive Officer position is weak compared to the council manager system seen in other counties. In some areas, much of the work previously undertaken directly (in direct service organisations) by council employees has been privatised.

Functions and powers

| Arrangement | Upper tier authority | Lower tier authority |

|---|---|---|

| Non-metropolitan counties/Non-metropolitan districts | waste management, education, libraries, social services, transport, strategic planning, consumer protection, police, fire | housing, waste collection, council tax collection, local planning, licensing, cemeteries and crematoria |

| Unitary authorities |

housing, waste management, waste collection, council tax collection, education, libraries, social services, transport, planning, consumer protection, licensing, cemeteries and crematoria†, police and fire come under shire councils | |

| Metropolitan boroughs | housing, waste collection, council tax collection, education, libraries, social services, transport, planning, consumer protection, licensing, police, fire, cemeteries and crematoria† | |

| Greater London/London boroughs | transport, strategic planning, regional development, police, fire | housing, waste collection, council tax collection, education, libraries, social services, local planning, consumer protection, licensing, cemeteries and crematoria† |

| Combined authorities/constituent authorities | transport, economic development, regeneration & various (depends on devolution deal) | Dependent on type and combined authority arrangement |

† = in practice, some functions take place at a strategic level through joint boards and arrangements

Under the Local Government Act 2000, councils have a general power to "promote economic, social and environmental well-being" of their area. However, like all public bodies, they were limited by the doctrine of ultra vires, and could only do things that common law or an Act of Parliament specifically or generally allowed for. Councils could promote Local Acts in Parliament to grant them special powers. For example, Kingston upon Hull had for many years a municipally owned telephone company, Kingston Communications.

The Localism Act 2011 introduced a new "general power of competence" for local authorities, extending the "well-being" power with the power to "do anything that individuals generally may do". This means, in effect, that nothing otherwise lawful that a local authority may wish to do can be ultra vires. As of 2013 this general power of competence is available to all principal local authorities and some parish councils.[7][8] However, it has not been extensively used.[9]

Funding

Local councils are funded by a combination of central government grants, Council Tax (a locally set tax based on house value), Business Rates, and fees and charges from certain services including decriminalised parking enforcement. Up to 15 English councils risk insolvency, the National Audit Office maintains, and councils increasingly offer, “bare minimum” service.[10] The New Local Government Network maintains most local authorities will only be able to provide the bare minimum of services five years from 2018.[11]

Many of these funding sources are hypothecated (ring-fenced) - meaning that they can only be spent in a very specific manner - in essence, they merely pass through a council's accounts on their way from the funding source to their intended destination. These include:

- Dedicated Schools Grant - funds any schools that are still managed by the local authority, rather than being autonomously run (principally academies, which are funded directly by central government); less than half of state-funded secondary schools are still reliant on this funding source. The Dedicated Schools Grant is often relatively large - and can typically be about 1/3 of all council funding. Hypothecation for this has been in place since 2006.

- Housing Benefit Grant - funds housing benefit claims made in the council area, and related administration. Housing Benefit is being gradually replaced by an element within Universal Credit, and Pension Credit; these replacements will be administered centrally, and provided directly to claimants from central government.

- Health & Wellbeing grant. This is intended to be used for measures to improve public wellbeing; the term has deliberately been left undefined, but is not intended to fund measures targeted at specific individuals (such as healthcare or social care), which are funded by other mechanisms. For example, this could be used to plant additional trees on streets, or to tidy the appearance of buildings.

- Rents from tenants of council-owned housing. By law, these must in fact be paid into a distinct Housing Revenue Account, which can only be used for maintenance, management, and addition, of the council-owned housing stock, and cannot be used for funding any other council expenditure.

- Fines and charges related to vehicle parking, and local road restrictions. By law, these can only be used to fund parking services, road repairs, enforcement of road restrictions, etc.

The other main central government grant - the Revenue Support Grant - is not hypothecated, and can be spent as the council wishes. For many decades, Business Rates were gathered locally, pooled together nationally, and then redistributed according to a complicated formula; these would be combined with the Revenue Support Grant to form a single Formula Grant to the council. Since 2013, a varyingly sized chunk of Business Rates is retained locally, and only the remainder is pooled and redistributed; the redistribution is according to a very basic formula, based mainly on the size of the 2013 Formula Grant to the relevant council, and is now provided to the council independently of the Revenue Support Grant.

Council Tax

Setting the rate

When determining their budget arrangements, councils make a distinction between hypothecated funding and non-hypothecated funding. Consideration of all funding in general is referred to as gross revenue streams, while net revenue streams refers to funding from only non-hypothecated sources.

Historically, central government retained the right to cap an increase in Council Tax, if it deemed the council to be increasing it too severely.[12] Under the Cameron-Clegg coalition, this was changed. Councils can raise the level of council tax as they wish, but must hold a local referendum on the matter, if they wish to raise it above a certain threshold set by central government, currently 2%.

Billing authorities

Council Tax is collected by the principal council that has the functions of a district-level authority. It is identified in legislation as a billing authority, and was known as a rating authority. There are 326 billing authorities in England that collect council tax and business rates:[13][14][15]

- 201 non-metropolitan district councils

- 55 unitary authority councils

- 36 metropolitan borough councils

- 32 London borough councils

- City of London Corporation

- Council of the Isles of Scilly

Precepting authorities

Precepting authorities do not collect Council Tax directly, but instruct a billing authority to do it on their behalf by setting a precept. Major precepting authorities such as the Greater London Authority and county councils cover areas that are larger than billing authorities. Local precepting authorities such as parish councils cover areas that are smaller than billing authorities.[14]

The precept shows up as an independent element on official information sent to council tax payers, but the council bill will cover the combined amount (the precepts plus the core council tax). The billing authority collects the whole amount, and then detaches the precept and funnels it to the relevant precepting authority.

Levying bodies

Levying bodies are similar to precepting authorities, but instead of imposing a charge on billing authorities, the amount to be deducted is decided by negotiation. The Lee Valley Regional Park Authority is an example of a levying body. Voluntary joint arrangements, such as waste authorities are also in this category.

Aggregate External Finance

Aggregate External Finance (AEF) refers to the total amount of money given by central government to local government. It consists of the Revenue Support Grant (RSG), ringfenced and other specific grants, and redistributed business rates. A portion of the RSG money paid to each authority is diverted to fund organisations that provide improvement and research services to local government (this is referred to as the RSG top-slice), for example the Local Government Association.[16]

Funding shortfall

It is feared many local authority services will close or be cut because the government has not increased local authority funding in 2017-2018. Gary Porter of the Local Government Association fears authorities will have to cut back on collecting waste, filling potholes, maintaining parks, running children's centres and libraries due to increasing funding shortfalls. Porter said, “Councils, the NHS, charities and care providers remain united around the desperate need for new government funding for social care. By continuing to ignore these warnings, social care remains in crisis and councils and the NHS continue to be pushed to the financial brink.”[17] Children at risk get inadequate help because councils are under resourced. What help children at risk get depends on the postcode lottery and varies between local authorities.[18] Over 500 children's centres have closed since 2010 due to funding cuts and more closures are planned. Children's centres support parents struggling with parenting skills and give children the best start in life.[19]

The 'Association for Public Service Excellence' (Apse) published a report claiming largescale funding cuts and differences between authorities were “changing the very nature of local government.” Universal services which are core functions of Local Authorities were being dismantled. “These services need defending in their own right as part of wider defence of local government as a whole.” Deprived areas experienced the greatest fall in spending, 'food and water safety inspection, road safety and school crossings, community centres and services aimed at cutting crime – such as CCTV – and support for local bus services' were among areas cut. Neighbourhood services have been cut against a framework of unparalleled cuts in local government spending as a proportion of the economy. In 2010-11, it amounted to 8.4% of the economy, but fell to 6.7% by 2015-16. By 2020-21, it is projected to be down to 5.7%, a 60-year low. Cuts to social care received more attention but the neighbourhood services, including highways and transport, cultural services, environmental services and planning, has been cut far more severely according to the report. Paul O'Brien of Apse said: “In eight years, local government spending will have dropped from two thirds of that of central government's to half. There is a slow but very harmful dismantling of neighbourhood services that marks a profound change in what local public services our communities can expect to receive. From emptying bins to running swimming pools to providing high quality local parks, spending on these services which communities really value has been cut harder and faster than any other area of public service spend. Centrally driven austerity has fallen hardest on local shoulders.”[20] Swimming pools, sports halls and leisure centres are at risk of closure due to lack of funding. This is despite growing health problems like obesity, heart disease and diabetes. Many pools and sports facilities are old and in need of refurbishment but local authotities do not have the funds to refurbish them.[21]

Anne Longfield said cuts of 60% to the Sure Start programme and to youth services since 2009 have removed safety provision for at risk children. This resulted in more children being taken into care, which is more expensive and potentially damaging. Longfield called for the recent trend to spend money on expensive child protection rather than prevention to be reversed. Longfield also maintains lack of preventive work leads to children's situation deteriorating, increasing numbers of children are excluded from school and become invoved with criminal gangs. Longfield maintains there will be a lifetime cost to those children who have "only one childhood and only one chance to grow up"[22] Children in care have way below average educational actievement and are more likely to get involvd in the criminal justice system. Just 14% got five A*-C GCSEs, including maths and English, in 2015. The national average is 55%. Children in care are five times more frequently excluded from school and 39% of children in secure training centres were in care.[23]

Tim Loughton blames inadequate funding for lack of provision for children at risk. Loughton said children who self-harmed, were physically abused, or in families with domestic violence, were subject to a postcode lottery and the help they got depended on where they lived with some getting no help. Budgetary considerations often determine how much help is given.[24] Following the decisions by Northamptonshire County Council and East Sussex County Council to cut services drastically Anne Longfield said, “I’m extremely worried that the financial difficulties that Northamptonshire county council are facing will mean that they are not going to be protecting the services for the most vulnerable children, which could have catastrophic consequences for those children. [researh by the Institute for Fiscal Studies demonstrated] half of all the spending on children’s services goes on the 70,000 children who are in care, if you add in those who are on the child protection registers, that’s over 80%, leaving very, very little for any others”. Longfield called on the government to ensure statutory protection for local authority children's services. She said, “Councils have been warning for some time that they are not going to be able to meet their statutory requirements. I can see and hear every day from families and children who simply can’t get help.” She also said, “If you don’t help children when the problems aren’t at crisis point then the crisis is going to be developing and also it is going to be much more costly when it gets to that point.” Longfield said 1.5 million children in England were in families with high needs like "severe mental health problems or domestic violence in the home" and did not receive, "substantial help."[25][26]

Councils are running deficits because there is not enough funding to protect vulnerable children. According to The Observer before the 2017 budget concerned ministers many times approached the Treasury, but requests were refused. MP's have warned Theresa May that without action the funding crisis could cause another tragedy like the death of Baby P. Referrals to children’s social care rose by 100,000 children in ten years and child protection plans to assess their risk of harm and keep them safe, rose by 23,000. Roy Perry said, “These figures clearly show the huge and increasing financial pressures children’s services are under, with many councils being pushed to the brink by unprecedented demand. It is not just increased pressure for care for the elderly causing the problem for local authority budgets. Councils have done what they can to protect spending on children’s services and have spent over £800m more than they had budgeted on children’s social care. Councils do not want to cut the very services which are designed to help children and families before problems begin or escalate to the point where a child might need to come into care. We are absolutely clear that, unless new funding is found, these vital services, which keep children safe from harm and the worst abuses of society, will reach a tipping point.”[27]

By 2019 spending on local authority programmes to cut smoking, to tackle obesity, to reduce drug and alcohol abuse, also to improve sexual health will have been cut by 23.5% over 5 years. This is seen as short sighted as it will increase pressure on the NHS.[28]

Northamptonshire County Council is at risk of insolvency and according to the National Audit Office up to 15 other Local authorities could be at risk.[29]

Many local authorities aare cutting contraceptive services. It is feared this will lead to increased unplanned pregnancies and abortions. Prof Helen Stokes-Lampard of the Royal College of GPs said, "It's extremely concerning to hear of such large-scale cuts, or plans to cut, contraceptive services, across England - actions that will potentially affect millions of women. It seems bizarre when there is strong evidence that investing in good contraception services is one of the most cost-effective healthcare interventions available. But the most recent data shows prescriptions for LARCs - reliable, cost-effective contraception - decreasing. We're at a crossroads, whereby all the progress we've made is under serious threat, and we fear it will be some of our most vulnerable patients who are affected most."[30]

Further drastic cuts are feared for 2019. The 'County Council Network' fears "unpalatable cutbacks" in 2019 while councils find at least £1bn savings to prevent a £1.5bn shortfall by 2020. Some local authorities may be forced to cut all non statutory services to ensure that they can fund their statutory obligations.[31]

Boundaries and names

Sizes of council areas vary widely. The most populous district in England is Birmingham (a metropolitan borough) with 1,073,045 people (2011 census), and the least populous non-metropolitan unitary area is Rutland with 37,369.[32] However, these are outliers, and most English unitary authorities have a population in the range of 150,000 to 300,000. The smallest non-unitary district in England is West Somerset at 34,675 people, and the largest Northampton at 212,069.[32] However, all but 9 non-unitary English districts have fewer than 150,000 people. Responsibility for minor revisions to local government areas falls to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England. Revisions are usually undertaken to avoid borders straddling new development, to bring them back into line with a diverted watercourse, or to align them with roads or other features.

Where a district is coterminous with a town, the name is an easy choice to make. In some cases, a district is named after its main town, despite there being other towns in the district. Confusingly, such districts sometimes have city status, and so for example the City of Canterbury contains several towns apart from Canterbury, which have distinct identities. Similarly the City of Winchester contains a number of large villages and extensive countryside, which is quite distinct from the main settlement of Winchester. They can be named after historic subdivisions (Broxtowe, Spelthorne), rivers (Eden, Arun), a modified or alternative version of their main town's name (Harborough, Wycombe), a combination of main town and geographical feature (Newark and Sherwood) or after a geographical feature in the district (Cotswold, Cannock Chase). A number of districts are named after former religious houses (Kirklees, Vale Royal, Waverley). Purely geographical names can also be used (South Bucks, Suffolk Coastal, North West Leicestershire). In a handful of cases entirely new names have been devised, examples being Castle Point, Thamesdown (subsequently renamed as Swindon) and Wychavon. Councils have a general power to change the name of the district, and consequently their own name, under section 74 of the Local Government Act 1972. Such a resolution must have two thirds of the votes at a meeting convened for the purpose.

Councils of counties are called "The X County Council", whereas district councils can be District Council, Borough Council, or City Council depending upon the status of the district. Unitary authorities may be called County Councils, Borough Councils, City Councils, District Councils, or sometimes just Councils. These names do not change the role or authority of the council.

Greater London is further divided into 32 London boroughs, each governed by a London Borough Council, and the City of London, which is governed by the City of London Corporation. In the London boroughs the legal entity is not the Council as elsewhere but the inhabitants incorporated as a legal entity by royal charter (a process abolished elsewhere in England and Wales under the Local Government Act 1972). Thus, a London authority's official legal title is "The Mayor and Burgesses of the London Borough of X" (or "The Lord Mayor and Citizens of the City of Westminster"). In common speech, however, "The London Borough of X" is used.

Metropolitan counties no longer have county councils, as these were abolished in 1986. They are divided into metropolitan districts whose councils have either the status of City Council or Metropolitan Borough Council.

Some districts are Royal boroughs, but this does not affect the name of the council.

Special arrangements

Joint arrangements

.svg.png)

Local authorities sometimes provide services on a joint basis with other authorities, through bodies known as joint-boards. Joint-boards are not directly elected but are made up of councillors appointed from the authorities which are covered by the service. Typically, joint-boards are created to avoid splitting up certain services when unitary authorities are created, or a county or regional council is abolished. In other cases, if several authorities are considered too small (in terms of either geographic size or population) to run a service effectively by themselves, joint-boards are established. Typical services run by joint-boards include policing, fire services, public transport and sometimes waste disposal authorities.

In several areas a joint police force is used which covers several counties; for example, the Thames Valley Police (in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire) and the West Mercia Police (in Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin, Herefordshire and Worcestershire). In the six metropolitan counties, the metropolitan borough councils also appoint members to joint county-wide passenger transport authorities to oversee public transport, and joint waste disposal authorities, which were created after the county councils were abolished.

Joint-boards were used extensively in Greater London when the Greater London Council was abolished, to avoid splitting up some London-wide services. These functions have now been taken over by the Greater London Authority. Similar arrangements exist in Berkshire, where the county council has been abolished. If a joint body is legally required to exist, it is known as a joint-board. However, local authorities sometimes create joint bodies voluntarily and these are known as joint-committees.[33]

City of London Corporation

The City of London covers a square mile (2.6 km²) in the heart of London. It is governed by the City of London Corporation, which has a unique structure. The Corporation has been broadly untouched by local government reforms and democratisation. It has its own ancient system of 25 wards, as well as its own police service. The business vote was abolished for other parts of the country in 1969, but due to the low resident population of the City this was thought impractical. In fact, the business vote was recently extended in the City to cover more companies.

Further reforms to local government

Reforms 2006 to 2010

The Labour Government released a Local Government White Paper on 26 October 2006, Strong and Prosperous Communities, which dealt with the structure of local government.[34][35][36][37] The White Paper did not deal with the issues of local government funding or of reform or replacement of the Council Tax, which was awaiting the final report of the Lyons Review.[38] A Local Government Bill was introduced in the 2006–07 session of Parliament.[39] The White Paper emphasised the concept of "double devolution", with more powers being granted to councils, and powers being devolved from town halls to community levels. It proposed to reduce the level of central government oversight over local authorities by removing centrally set performance targets, and statutory controls of the Secretary of State over parish councils, by-laws, and electoral arrangements.

The white paper proposed that the existing prohibition on parish councils in Greater London would be abolished, and making new parishes easier to set up. Parish councils can currently be styled parish councils, town councils or city councils: the White Paper proposes that "community council", "neighbourhood council" and "village council" may be used as well. The reforms strengthen the council executives, and provided an option between a directly elected mayor, a directly elected executive, or an indirectly elected leader – all with a fixed four-year term. These proposals were enacted under the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007.

A report released by the IPPR's Centre for Cities in February 2006, City Leadership: giving city regions the power to grow, proposed the creation of two large city-regions based on Manchester and Birmingham: the Birmingham one would cover the existing West Midlands metropolitan county, along with Bromsgrove, Cannock Chase, Lichfield, North Warwickshire, Redditch and Tamworth, while the Manchester one would cover the existing Greater Manchester along with the borough of Macclesfield.[40] No firm proposals of this sort appear in the White Paper. Reportedly, this had been the subject of an internal dispute within the government.[41]

Reforms 2010 to 2015

Since the Coalition Government was elected in 2010 while the thrust of policy is to further promote localism, as within the introduction of the Localism Bill in December 2010, which became the Localism Act 2011 on receiving Royal Assent on 15 November 2011[42] the Coalition has also declared its intention to streamline past regulation, reform planning, re-organise the police and health authorities, has abolished a whole tier of regional authorities and in its one-page Best Value Guidance.[43] voiced its intention to repeal the Sustainable Communities Act and other New Labour commitments like the 'Duty to Involve'. It has however created the Greater Manchester Combined Authority and signalled intent, under the 'City Deals' process promoted under the Localism Act, to create further combined authorities for the North East, South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire as nascent city regions. Another aspect of the Localism Act is increased opportunities for Neighbourhood Forums.

The Regional Assemblies and Regional Development Agencies were abolished in 2010 and 2012 respectively. The Local authority leaders' boards also had their funding cut in 2011, though continue as unelected consultative forums and as regional groupings for the Local Government Association.

Reforms 2015 to present

Further consolidation of local government through the formation of unitary authorities in existing two-tier areas have been proposed under the premiership of Theresa May.

Dorset

In 2017, it was proposed that two unitary authorities be formed to cover the ceremonial county of Dorset. One of the authorities would consist of the existing unitary authorities of Bournemouth, Poole and the non-metropolitan district of Christchurch, the other would be composed of the remainder of the county. [44] In November 2017, Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, Sajid Javid stated that he was "minded to approve the proposals" and a final decision to implement the two unitary authority model was confirmed in February 2018. Statutory instruments for the creation of two unitary authorities, to be named Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council and Dorset Council, have been made and shadow authorities for the new council areas have been formed. [45] [46] [47]

Buckinghamshire

Two competing plans have also been drawn up for Buckinghamshire. One plan would see the abolition of the four district councils resulting in the existing county council becoming a unitary authority. The other plan would see the formation of two unitary authorities, one authority would be formed through the merger of the three existing districts of Chiltern, South Bucks and Wycombe, with the other formed by the existing Aylesbury Vale district becoming a unitary authority. [48] [49] In March 2018, Communities Secretary Sajid Javid indicated that the single unitary authority option would be pursued over the two unitary authority model. [50] His successor in the post has not expressed an opinion.

Northamptonshire

In March 2018, an independent report commissioned by the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, proposed structural changes to local government in Northamptonshire. These changes would see the existing county council and district councils abolished and two new unitary authorities created in their place. [51] One authority would consist of the existing districts of Daventry, Northampton and South Northamptonshire and the other authority would consist of Corby, East Northamptonshire, Kettering and Wellingborough districts.[52]

See also

References

- ↑ "Briefing Paper Local government in England: structures" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ "Local Councils (Town, Parish)". Hinckley & Bosworth Borough Council. 21 April 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ "Town and Parish Councils". Kettering Borough Council. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ Millward, Paul Civic ceremonial; a handbook, history and guide for mayors, councillors and officers (Shaw & Sons, 1998) ISBN 0 7219 0163 8

- ↑ Chair of the Council: Middlesbrough Council

- ↑ Polly Toynbee (8 May 2008). "This vogue for localism has not solved voter antipathy". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Localism Act 2011".

- ↑ Government, Department for Communities and Local. "Explanatory Notes to Localism Act 2011".

- ↑ Samir Jeraj. "The jury is still out on the general power of competence". the Guardian.

- ↑ Northamptonshire council backs 'bare minimum' service plan The Guardian

- ↑ "Most local authorities will only deliver the bare minimum in five years' time". www.nlgn.org.uk. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "Raynsford reveals capped councils". BBC News Online. 14 May 2004.

- ↑ "Council tax collection" (PDF). Audit Commission.

- 1 2 "Parishes and other local precepting authorities: 2013-14 England" (PDF).

- ↑ Council Tax Handbook, Geoff Parsons, Tim Rowcliffe Smith, Tim Smith, (2006), Taylor & Francis

- ↑ http://www.local.gov.uk/documents/10180/12129/L14-99+LGA+business+plan+2014-15_A5_v13/4391618f-454e-406c-ba8c-6d5dadf5da56

- ↑ Council funding freeze 'means cuts to many essential services' The Guardian

- ↑ MPs slam funding crisis and 'postcode lottery' of children's services The Guardian

- ↑ More than 500 children's centres have closed in UK since 2010 The Guardian

- ↑ Council spending on 'neighbourhood' services falls by £3bn since 2011 The Guardian

- ↑ Pools and sports halls 'could be forced to close' BBC

- ↑ Early years cuts 'pushing more children into care' in England The Guardian

- ↑ Silent crisis of inadequate councils caring for thousands of children The Guardian

- ↑ Underfunding to blame for child protection 'crisis', says report The Guardian

- ↑ Vulnerable children facing 'catastrophe' over crisis-hit councils BBC

- ↑ Council funding crisis could be 'catastrophic' for vulnerable children The Guardian

- ↑ Revealed: cash crisis pushing child services to tipping point The Observer

- ↑ Fears of future strain on NHS as councils slash health programmes The Observer

- ↑ Northamptonshire forced to pay the price of a reckless half-decade The Guardian

- ↑ Women 'struggling to access contraception' BBC

- ↑ '£1bn in unpalatable county council cuts' ahead in England BBC

- 1 2 "2011 Census: KS101EW Usual resident population, local authorities in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ Joseph Rowntree Foundation (1995). "The working of joint arrangements". Local and Central Government Relations Research 37.

- ↑ "Councils to get fresh law powers". BBC News Online. 26 October 2006.

- ↑ Strong and Prosperous Communities, Cm 6939. Department for Communities and Local Government. 26 October 2006.

- ↑ "Local Government White Paper". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 26 October 2006. col. 1657–1659.

- ↑ "White Paper proposes stronger mayors and more power to English communities". CityMayors. 30 October 2006.

- ↑ "Council tax system to be reformed". BBC News Online. 2 July 2004.

- ↑ "Kelly offers councils more freedom under tougher leaders". The Guardian. 27 October 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ City Leadership: executive summary (PDF). Institute for Public Policy Research. February 2006.

- ↑ "Government pushes for elected mayor in Brum". Birmingham Post. 26 October 2006.

- ↑ "The Localism Act". Department for Communities and Local Government. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Best Value Statutory Guidance". Department for Communities and Local Government. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Future Dorset - Two new authorities for Dorset". futuredorset.co.uk. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "The Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole (Structural Changes) Order 2018". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ https://bcpjointcommittee.wordpress.com/

- ↑ "Shadow Dorset Council". Shadow Dorset Council. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "Decision on future of councils in Bucks could be decided imminently". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ https://www.wycombe.gov.uk/uploads/public/documents/About-the-council/Modernising-local-government/Proposal-for-modernising-local-government-in-Buckinghamshire.pdf

- ↑ "Unitary plan for Buckinghamshire backed". 12 March 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "Troubled council 'should be scrapped'". 15 March 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "Northamptonshire County Council 'should be split up', finds damning report". Retrieved 10 September 2018.

External links

- Department for Communities and Local Government – Local Government

- Info4local.gov.uk – National policies affecting local government

- Local Government Association for England and Wales

- New Local Government Network (NLGN)

- LocalGov.co.uk – News updates on UK local government

- Guardian Special Report - Local Government

- Guardian Special Report - Local Politics

- Local.gov.uk – LGA and related bodies

- Local Government Information Unit

- Centre for Cities

- Direct Gov – List of local councils

- OpenlyLocal — Raw local government data feeds

- The Local Government Forum - discussion boards for most councils in the UK - Data supplied by OpenlyLocal