Universal Credit

Universal Credit is a United Kingdom social security payment that is intended to simplify working age benefits and to incentivise paid work. It replaces six means-tested benefits and tax credits: income-based Employment and Support Allowance, Income Support, income-based Jobseeker's Allowance, Housing Benefit, Working Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit.[1][n 1]

The new policy was announced in 2010 at the Conservative Party annual conference by the Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith, who said it would bring "fairness and simplicity" to the social security system. At the same venue the Welfare Reform Minister, Lord David Freud, described their scheme as a "once in many generations" reform.[2] A key feature is that payments will taper off as the recipient moves into work, not suddenly stop, thus avoiding a 'cliff edge' that is said to 'trap' people in poverty. Universal Credit was legislated for in the Welfare Reform Act 2012.

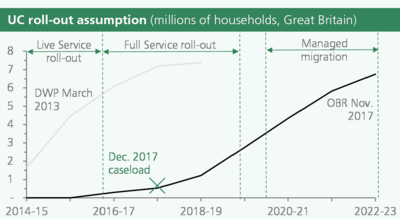

In 2013 the new benefit began to be rolled out gradually to Jobcentres,[3] initially focusing on claimants whose circumstances were the least complex: single adults without housing costs. [4] By October 2018, more than one million people were receiving the new benefit.

Universal Credit has faced criticism. Payments are made monthly, with a waiting period of at least five weeks before the first payment. This can particularly affect claimants of housing benefit, leading to arrears. Former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown has warned that a hard-to-navigate application system (from 2019, established recipients of the six older working-age benefits will have to reapply online for Universal Credit) and cuts to the value of the payment risk bringing a million more children into poverty and adding to demand on food banks.[5]

There have been problems with the overall management of the project and with the IT system on which Universal Credit relies. Implementation costs, initially forecast to be around £2 billion, later grew to over £12 billion. More than three million recipients of "legacy" benefits (the six benefits Universal Credit is replacing) were expected to have been transferred to the new system by 2017; but the timetable slipped and, under current plans, the full move will not be completed before 2022.[6]

In 2015 the Chancellor, George Osborne, announced a future £5 billion a year cut to the Universal Credit budget after his attempt to cut Tax Credits that year was thwarted by parliament.[7] The Resolution Foundation has argued that this cut, which will be felt more keenly as millions more people transfer to Universal Credit,[8] risks the new system failing to achieve its original purpose of incentivising work in low-income households.[9]

Background

The Universal Credit mechanism was itself first outlined as a concept in a 2009 report, Dynamic Benefits, by Iain Duncan Smith's thinktank the Centre for Social Justice.[10] It would go on to be described by Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith at the Conservative Party annual conference in 2010.[11] The initial aim was for it to be implemented fully over four years and two parliaments, and to merge the six main existing benefits (income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance, income-related Employment and Support Allowance, Income Support, Working Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit and Housing Benefit) into a single monthly payment, as well as cut the considerable cost of administering six independent benefits, with their associated computer systems.

Unlike existing benefits like Income Support, which had a 100% withdrawal rate, Universal Credit was designed to gradually taper away – like tax credits and Housing Benefit – allowing claimants to take part-time work without losing their entitlement altogether. In theory, it makes claimants better off taking on work, as they keep at least a proportion of the money they earn.[12] But reductions in funding and changes to withdrawal rates left commentators on either side of the debate to question whether it would actually make work pay. The Daily Telegraph claimed "part-time work may no longer pay", and "some people would be better off refusing" part-time work[13] and in the Guardian Polly Toynbee wrote "Universal credit is simple: work more and get paid less".[14] Finally, the "Minimum Income Floor" used when calculating Universal Credit for self-employed claimants may make it much less worthwhile for large parts of the population to work for themselves.[15]

Relationship to other proposed welfare policies

Universal Credit has some similarities to Lady Williams' idea of a negative income tax, but it should not be confused with the universal basic income policy idea. There is some debate as to whether Universal Credit should be described as "universal", given it is both subject to income cut-offs and requires some claimants to be available for work.[16][17]

Implementation

Universal Credit is part of a package of measures in the Welfare Reform Act 2012, which received Royal Assent on 9 March 2012. The Act delegates the its detailed workings to regulations, most of which were published as the Universal Credit Regulations 2013.[18] Related regulations appeared in a range of other statutory instruments also.[19]

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) announced in February 2012 that Universal Credit would be delivered by selected best-performing DWP and Tax Credit processing centres.[20] Initially, the announcement made clear that local authorities (responsible for administering payment of Housing Benefit, a legacy benefit to be incorporated into the scheme) would not have a significant part in delivering Universal Credit. However, the Government subsequently recognised there may be a useful role for local authorities to play when helping people access services within Universal Credit.[21]

Philip Langsdale, Chief Information Officer at DWP, who had been leading the programme, died in December 2012, and in previous months there had also been significant personnel changes. Project Director Hillary Reynolds resigned in March 2013 after just four months, leaving the new Chief Executive of Universal Credit to take on her role.[22] Writing in 2013, Emma Norris of the Institute for Government argued the original timetable for implementation of Universal Credit was "hugely overambitious",[23] with delays due to IT problems and senior civil servants responsible for the policy changing six times.[23]

A staff survey, reported in The Guardian on 2 August 2013,[24] quoted highly critical comments from Universal Credit implementation staff. On 31 October 2013, in another article[25] said to be based on leaked documents, the paper reported that only 25,000 people – about 0.2% of all benefit recipients – were projected to transfer to the new programme by the time of the next general election in May 2015. In the event, over 100,000 people had made a claim for Universal Credit by May 2015.[26]

A pilot in four local authority areas was due to precede national launch of the scheme for new claimants (excluding more complex cases such as families with children), in October 2013, with full implementation to be completed by 2017. Due to persistent computer system failures and delays in implementation, only one pilot, in Ashton-under-Lyne,[27] went ahead by the expected date. The other three pilots went ahead later in the summer, and were met by staff protests.[28]

The roll-out of Universal Credit in the Northwest of England was limited to new, single, healthy claimants, later extended to couples, then families, in the same area, reflecting the gradual maturing of different aspects of the computer system. Once the Northwest roll-out was largely complete, the government gradually extended Universal Credit to new single healthy claimants in the rest of the British mainland, nearly completing this roll-out as of 13 March 2016. It was expected that this would gradually be extended to couples and families outside the Northwest once the roll-out to UK mainland single claimants was completed. In Northern Ireland, implementation was held up by disputes over policy and funding between feuding parties in the Northern Ireland assembly; the roll-out of Universal Credit in Northern Ireland began in September 2017.

As of 2018 one third of claimants have their benefit reduced to pay rent, council tax and utility bill arreas. This pushed people who already have little further into poverty. Abby Jitendra of the Trussell Trust said this can lead to “the tipping point into crisis. (...) Repaying an advance payment, for example, can be an unaffordable expense when taken from a payment that wasn’t enough to start with, pushing people further into debt at the time when support is most needed.” Gillian Guy of Citizens Advice said, “Deductions from universal credit can make it harder for people to get by. People receiving universal credit are unlikely to have much slack in their budgets, so even small amounts can put a huge strain on their finances. Building on last year’s improvements to universal credit, the government now needs to ensure deductions are made at a manageable rate and take a person’s ability to cover their expenses into account.” Charlotte Hughes who advises benefit recipients, said deductions were impossible to predict and often done with no warning. “The first time somebody knows that money’s been taken out of their account is when they go to the bank. It’s just a minefield. Living with that stress that you don’t know what money you’re going to get from week to week, from month to month, that makes you ill – and that’s before you can’t eat, and before you can’t look after your kids properly. It’s rampant.”[29]

Pilots

The scheme was originally planned to begin in April 2013,[30] in four local authorities – Tameside (containing Ashton-under-Lyne), Oldham, Wigan and Warrington, with payments being handled by the DWP Bolton Benefit Centre – but was later reduced to a single area (Ashton) with the others due to join in July. The pilot would initially cover only about 300 claims per month for the simplest cases of single people with no dependent children, and was to extend nationally for new claimants with the same circumstances by October, with a gradual transition to be complete by 2017. (One tester of the new system in April noted that the online forms took around 45 minutes to complete, and there was no save function.)

In March 2013 it was reported[31] that final Universal Credit calculations would be made manually on spreadsheets during the pilot, with the IT system being limited to booking appointments and storing personal details. It was separately reported[32] that no claimants turned up in person at the town hall on the first day of the scheme.

The Financial Times reported[33] that the October national roll-out of Universal Credit would now begin in a single Jobcentre (or possibly a "cluster" of them) in each region and that in December 2012 Hilary Reynolds, who had recently been appointed programme director but had moved shortly thereafter, stated in a letter to local authorities: "For the majority of local authorities the impact of [Universal Credit] during the year 2013–14 will be limited."

On 3 December 2013 the DWP issued statistics showing that, between April and 30 September, only 2,150 people had been signed up to Universal Credit in the four pilot areas.[34] The report confirmed that Universal Credit had been rolled out to Hammersmith in October, followed by Rugby and Inverness in November, and was to expand to Harrogate, Bath, and Shotton by spring 2014.

Current status

In July 2018 the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Damian Green, announced a further 12 month delay to the planned implementation completion date to allow additional contingency time, taking that to 2022. This was the seventh rescheduling since 2013, pushing the implementation completion date to five years later than originally planned.[6]

As of February 2016, 364,000 people had made claims for Universal Credit. Government research stated "Universal Credit claimants find work quicker, stay in work longer and earn more than the Jobseekers' Allowance claimants."[4][35] Delays in payments were getting claimants into rent arrears and other debts, however.[36] Claimants may wait up to thirteen weeks for their first payment. Tenants can get into rent arrears more frequently on Universal Credit rather than Housing Benefit and many risk eviction and homelessness as a result. Landlords may refuse potential tenants on the benefit and marriages have broken up under the strain of coping with these delays and managing on Universal Credit.[37]

In April 2018 The Trussell Trust reported that their food banks in areas where universal credit had been rolled out had seen an average 52% rise in demand compared to the previous year.[38] The Trussell Trust fears a big increase in food bank use when Universal Credit is rolled out in April 2019. Emma Revie of Trussell said, “We’re really worried that our network of food banks could see a big increase in people needing help. Leaving 3 million people to wait at least five weeks for a first payment – especially when we have already decided they need support through our old benefits or tax credits system – is just not good enough. Now is the time for our government to take responsibility for moving people currently on the old system over, and to ensure no one faces a gap in payments when that move happens. Universal credit needs to be ready for anyone who might need its help, and it needs to be ready before the next stage begins.”[39]

Despite May’s promise to support those “just about managing”, working homeowners who currently get tax credits lose badly with universal credit. A million homeowners now getting tax credits will have less with the new system and lose on average £43 a week. 600,000 working single parents will lose on average £16 per week and roughly 750,000 households on disability benefits will lose on average £75 per week. Nearly 2 in 5 households receiving benefits will be on average worse off by £52 per week.[40] Up to thirty Conservative MP's are threatening to vote against the government over Universdal Credit. Heidi Allen said, “Significant numbers of colleagues on my side of the House are saying this isn't right and are coming together to say the chancellor needs to look at this again.”[41]

Policy

Universal Credit has four types of conditionality for claimants depending on their circumstances, ranging from being required to look for full-time work to not being required to find work at all (people in the unconditional group include the severely disabled and carers).[42]

Payments are made once a month directly into a bank or building society account. Any help with rent granted as part of the overall benefit calculation is included in the monthly payment and claimants must then pay landlords themselves.[43] It is possible in some circumstances to get an Alternative Payment Arrangement (APA), which allows payment of housing benefit direct to the landlord.[44]

Universal Credit claimants are also entitled to Personal Budgeting Support (PBS), which is aimed to help them adapt to some of the changes it brings, such as monthly payment.[44]

Costs

While the DWP had estimated administration costs for the roll-out of Universal Credit to be £2.2 billion, by August 2014 this estimate had risen to £12.8 billion over its "lifetime" and was later increased again to £15.8 billion.[45] Much of the increased cost was linked with software problems and duplication of systems needed to pay out new and legacy benefits. The initial roll-out proceeded much more slowly than had been originally planned, and led to the early departure of several senior leadership figures.[46] The National Audit Office maintains Universal Credit could incur higher administrative costs than the systems it replaces.[47]

Criticism

Universal Credit has been and is subject to many criticisms. Louise Casey fears recipients could become homeless and destitute. According to official figures 24% of new claimants wait over 6 weeks for full payment and many get behind with their rent.[48] Twelve Tory MPs including Heidi Allen wished the rollout delayed.[49] Local Authorities and recipients of Universal Credit feared claimants will become homeless in large numbers.[50] Gordon Brown maintains, “Surely the greatest burning injustice of all is children having to go to school ill-clad and hungry. It is the poverty of the innocent – of children too young to know they are not to blame. But the Conservative government lit the torch of this burning injustice and they continue to fan the flames with their £3bn of cuts. A return to poll tax-style chaos in a summer of discontent lies ahead.”[5]

Stephen Bush in The New Statesman[51] maintained that the group currently (October 2017) in receipt of Universal Credit was unrepresentative, consisting mainly of men under 30 who were more likely to find work as they did not have to juggle work obligations with dependent needs. He also argued that men under 30 were also more likely to be living with parents so delays in payments affected them less. Bush believed that when Universal Credit is extended to older claimants and women with dependents, fewer would get back to work easily and there would be more hardship.

Johnny Mercer said, "Universal credit has the potential to help people out of poverty by removing the disincentives to move into work in the previous system and allowing them to reach their full potential. A modern compassionate Conservative government simply must get it right though. This government can make the system better by smoothing the path from welfare into work with a fresh investment in universal credit in this budget." Mercer backed calls to increase funding for Universal Credit by stopping a plan to cut income tax.[52] Some claimants on Universal Credit feel they cannot get enough to live without resorting to crime.[53] One in five claims for Universal Credit fails because the claimant does not follow the procedure correctly and there are fears this is because the procedure is hard to understand.[54]

Food bank use has increased since Universal Credit started. Delays in providing money force claimants to use food banks, also Universal Credit does not provide enough to cover basic living expenses. Claiming Universal Credit is complex and the system is hard to navigate, many claimants cannot afford internet access and cannot access online help with claiming. A report by the Trussell Trust says, "Rather than acting as a service to ensure people do not face destitution, the evidence suggests that for people on the very lowest incomes … the poor functioning of universal credit can actually push people into a tide of bills, debts and, ultimately, lead them to a food bank. People are falling through the cracks in a system not made to hold them. What little support available is primarily offered by the third sector, whose work is laudable, but cannot be a substitute for a real, nationwide safety net."[55]

The National Audit Office maintains there is no evidence Universal Credit helps people into work and it is unlikely to provide value for money, the system is in many ways unwealdy and inefficient. There are calls for delays and for the system to be fixed before it is rolled out to millions of further claimants. Margaret Greenwood said, “The government is accelerating the rollout in the face of all of the evidence, using human beings as guinea pigs. It must fix the fundamental flaws in universal credit and make sure that vulnerable people are not pushed into poverty because of its policies.”[56]

Whistleblowers maintain the system is badly designed, broken and glitches regularly lead to hardship for claimants. Hardship can involve delays in benefit payment lasting weeks or reduction in payment by hundreds of pounds below what a claimant is entitled to. A whistleblower said, “The IT system on which universal credit is built is so fundamentally broken and poorly designed that it guarantees severe problems with claims.” he maintained the system is too complex and errorprone affecting payments and correction was frequently slow. “In practical terms, it is not working the way it was intended and it is having an actively harmful effect on a huge number of claimants.” Errors and delays add an average of three weeks to the official 35 day wait for a first payment forcing claimants into debt, rent areas and to food banks. Campaigners fear the situation could worsen in 2019 when 3 million claimants are moved to the new system. The Department of Work and Pensions is accused of being defensive and insular. One whistleblower said design problems existed due to failure to understand what claimants need, particularly when they do not have digital skills or internet access. He said, “We are punishing claimants for not understanding a system that is not built with them in mind.”[57]

In October 2018, Sir John Major warned against Universal Credit being introduced "too soon and in the wrong circumstances". Major argued that people who faced losing out in the short term had to be protected, "or you run into the sort of problems the Conservative Party ran into with the poll tax in the late 1980s".[58]

Reducing incomes

Multiple organisations have predicted that Universal Credits will cause families with children to be financially worse off. When fully operational, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that 2.1 million families will lose while 1.8 million will gain. Single parents and families with three children will lose an average £200 a month according to the Child Poverty Action Group and the Institute for Public Policy Research. Alison Garnham of the CPAG urged ministers to reverse cuts to work allowances and get Universal Credit, "fit for families". Garnham said: "Universal credit was meant to improve incentives for taking a job while helping working families get better off. But cuts have shredded it. And families with kids will see the biggest income drops." Since 2013 Universal Credit has changed nine times, most changes making it less generous. This includes cuts in work allowances, a freeze in credit rates for four years and (from April 2017)[59] the child credit being limited to two per family.

In October 2017, the Resolution Foundation estimated that that compared to the existing tax credit system: 2.2 million working families would be better off under the Universal Credit system, with an average increase in income of £41 a week. On the other hand, the Foundation estimated that 3.2 million working families would be worse off, with an average loss of £48 a week.[60]

In October 2018, the Work and Pensions Secretary, Esther McVey MP, admitted that "some people could be worse off on this benefit", but argued that the most vulnerable would be protected.[61]

Self-employed claimants

Research by the Low Income Tax Reform Group suggests self-employed claimants could be over £2,000 year[62] worse off than employed claimants on similar incomes. The problem applies with fluctuating income as Universal Credit assumes a fixed number of hours worked – the so-called Minimum Income Floor – in its calculation. The government has been urged to change this to allow the self-employed to base claims on their average incomes. Some claimants even could be over £4,000 a year worse off. Some people cannot find work except by being self-employed and such people will be discouraged from starting a business. Frank Field said, "Given what we now know about the hundreds of thousands of workers in the gig economy who earn less than the national living wage, it begs the question as to how many grafters and entrepreneurs are going to be further impoverished, or pushed deeper into debt, as a result of this new hole being opened up in the safety net."[63] Citizens Advice maintains that it risks "creating or exacerbating financial insecurity for the rising sector of the workforce in non-traditional work". People working in their own business will be affected as will those with seasonal work like agriculture and the hotel trade and those with varying overtime pay. 4.5 million people do work with varying hours while 4.8 million are self-employed most receiving in work benefits.[64]

Online applications

Professor John Seddon, an author and occupational psychologist, began a campaign in January 2011 for an alternative way to deliver Universal Credit, arguing it wasn't possible to deliver high-variety services through "cheaper" transaction channels, and would drive costs up. He wrote an open letter to Iain Duncan Smith and Lord Freud as part of a campaign to call halt to current plans and embark instead on a "systems approach". Seddon also launched a petition calling for Duncan Smith to: "rethink the centralised, IT-dominated service design for the delivery of Universal Credit".[65]

Echoing these concerns, Ronnie Campbell, MP for Blyth Valley, sponsored an Early Day Motion[66] on 13 June 2011 on the delivery of Universal Credit which was signed by thirty MPs: "That this House notes that since only fifteen per cent of people in deprived areas have used a Government website in the last year, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) may find that more Universal Credit customers than expected will turn to face-to-face and telephone help from their local authority, DWP helplines, Government-funded welfare organisations, councillors and their Hon. Member as they find that the automated system is not able to deal with their individual questions, particular concerns and unique set of circumstances".

Wait for payments and payment frequency

The Trades Union Congress has raised concerns about the delay – which is at least six weeks – between making a claim and receiving money.[67] The Work and Pensions Select Committee said waiting six-weeks for the first payment caused "acute financial difficulty". Reducing the delay would make the policy more likely to succeed.[68] Some claimants must wait eight months for their first payment. About 20% waited nearly five months and roughly 8% had to wait for eight months.[47] Committee Chair, Frank Field said, "Such a long wait bears no relation to anyone’s working life and the terrible hardship it has been proven to cause actually makes it more difficult for people to find work. "[69]

According to a report in The Guardian[70] Thousands of claimants get into debt, get behind with their rent and risk eviction due to flaws in Universal Credit and landlords and politicians want the system overhauled.

Due to ongoing problems an official inquiry[71] has been launched into Universal Credit. In October 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May said the six-week delay would continue[72], despite the concerns of many MPs including some in her own party. A study [73] for Southark and Croydon councils found substantial increase in indebtedness and rent arrears among claimants on Universal Credit compared with claimants on the old system. Referrals to food banks increased, in one case by 97 per cent.

End Hunger UK, a coalition of poverty charities and faith organizations said payment delays, administrative mistakes and failure to support claimants having difficulties with the online only system forced up food bank use. End Hunger UK urged ministers to do a systematic study of how universal credit affects claimants’ financial security. End Hunger UK urged a large cut in the time claimants wait for their first payment from at least five weeks to only two weeks, and maintain the long wait is financially crippling for claimants without savings. The Trussell Trust found demand for food aid rose an average of a 52% in universal credit areas in 2017, contrasted with 13% in areas where it had not been introduced. “It is simply wrong that so many families are forced to use food banks and are getting into serious debt because of the ongoing failings in the benefits system,” said Paul Butler, Bishop of Durham.[74]

Direct payments to tenants

Direct payment of the housing component of Universal Credit (formerly Housing Benefit) to tenants has been the subject of controversy. Although Housing Benefit has long been paid to most private sector tenants directly, for social housing tenants it has historically been paid directly to their landlords. As a result, implementation of a social housing equivalent to the Local Housing Allowance policy, which has been present in the private sector without comment for over a decade, has widely been perceived as a tax on having extra bedrooms, rather than the tenant making up a shortfall in the rent arising from a standardisation of their level of benefit.

The Social Security Advisory Committee have argued that the policy of direct payments requires "close monitoring" so as to make sure Universal Credit does not further discourage landlords from renting to people on benefits.[75]

Disincentive to save

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has argued that Universal Credit is a disincentive for people to save money.[76]

Impact on the self-employed

The Resolution Foundation has warned that Universal Credit will have a detrimental effect on self-employed people, because the level of Universal Credit awarded does not fully take account of any dramatic changes in their income from month to month.[77]

According to the Child Poverty Action Group, Universal Credit may affect the low-paid self-employed and anyone who makes a tax loss (spends more on tax-deductible expenses than they receive in taxable income) in a given tax year.[78]

Impact on disabled people

Citizens Advice research argued that 450,000 disabled people and their families would be worse off under universal credit.[79][80]

Impact on passported benefits

The Daily Mirror reported an example of a claimant who was moved over to Universal Credit from a "legacy benefit" and whose passported benefits, such as free school meals, were withdrawn in error.[81]

Domestic abuse

Universal Credit payments go to one person in each household, so abuse victims and their children are often left dependent according to a Work and Pensions Committee report and abusers can exert financial control. It is feared this can facilitate abuse and enable bullying. Financial abuse is also facilitated, one abuse survivor said to the committee that "[the abusive partner] will wake up one morning with £1,500 in his account and piss off with it, leaving us with nothing for weeks." Committee chair, Frank Field said, "This is not the 1950s. Men and women work independently, pay taxes as individuals, and should each have an independent income. Not only does UC's single household payment bear no relation to the world of work, it is out of step with modern life and turns back the clock on decades of hard-won equality for women." MPs listened to evidence that abuse victims found the whole of their income, including money intended for the children, went into the abuser's bank account. The report noted the single household payment caused difficulties for victims wanting to leave and said, "there is a serious risk of Universal Credit increasing the powers of abusers". The report called for all Job Centres to have a private room where people at risk of abuse could state their concerns confidentially. There should also be a domestic abuse specialist in each Job Centre who could alert other staff to signs of abuse. Scotland wants to split payments by default but needs the DWP to change the IT system. The report wants the department to work with Scotland and test a new split payment system. Katie Ghose of Women's Aid called on the government to implement the report and stated, "It is clear from this report that there are major concerns about the safety of Universal Credit in cases where there is domestic abuse."[82][83]

The campaign group Women's Aid have argued that as Universal Credit benefits are paid as a single payment to the household, this has negative consequences for victims of domestic abuse.[84] The Guardian also argued the change disempowers women, preventing them from being financially independent.[85] Women's Aid and the TUC jointly did research showing 52 per cent of victims living with their abuser claimed financial abuse prevented them from leaving. Under Universal Credit when a couple separates, one person must inform the DWP, and make a fresh claim, which takes at least five weeks to process. Someone without money, and possibly with children cannot manage such a wait. Katie Ghose said, "We're really concerned that the implications for women for whom financial abuse is an issue have not been fully thought through or appreciated by the government." Jess Phillips stated, "What we are doing is essentially eliminating the tiny bit of financial independence that at woman might have had." And, she added, the DWP keeps no data on whether Universal Credit goes to men or to women, therefore the magnitude of the problem cannot be measured.[86]

Impact on families

In the report Pop Goes the Payslip the advice organisation Citizens Advice highlighted examples of people in work worse off under Universal Credit than under the 'legacy' benefits it replaces.[87] Similarly, a report from 2012 by Save the Children highlights how "a single parent with two children, working full-time on or around the minimum wage, could be as much as £2,500 a year worse".[88]

Work disincentives

A House of Commons Library briefing note raised the concern that changes to Universal Credit that were scheduled to take effect in April 2016 might make people reluctant to take more hours at work:

There is concern that families transferring to Universal Credit as part of the managed migration whose entitlement to UC is substantially lower than their existing benefits and tax credits might be reluctant to move into work or increase their hours if this would trigger a loss of transitional protection, thereby undermining the UC incentives structure.[7]

The very long application and assessment hiatus also discourages UC recipients from moving off Universal Credit entirely, for more than six months, fearful having to undergo repeated and very long waiting periods, with no income, resulting because of redundancy and/or loss of temporary employment for legitimate reasons necessitating reapplication for Universal Credit from scratch.

Internal criticisms

A freedom of information request was made by Tony Collins and John Slater in 2012. They sought the publication of documents detailing envisioned problems, problems that arose with implementation, and a high-level review.[89]

In March 2016, a third judicial case ordered the DWP to release the documents. The government's argument against releasing the documents was the possibility of a chilling effect for the DWP and other government departments.[89]

IT problems

Universal Credit has been dogged by IT problems. A DWP whistleblower told Channel 4's Dispatches in 2014 that the computer system was "completely unworkable", "badly designed" and "out of date".[90] A 2015 survey of Universal Credit staff found that 90% considered the IT system inadequate.[91]

Telephone problems

Claimants on low income were forced to pay for long telephone calls. Citizen’s Advice in England carried out a survey in summer 2017 which found an average waiting time of 39 minutes with claimants often needing to make repeated calls. Nearly a third of respondents said they made over 10 calls. The government was urged to make telephone calls over Universal Credit free for claimants[92] and has done this.[93]

See also

Further reading

- Centre for Social Justice (2009), Dynamic Benefits: Towards welfare that works Published by: Centre for Social Justice

- Gillies, A., Krishna, H., Paterson, J., Shaw,J., Toal, A. and Willis, M. (2015) Universal Credit: What You Need To Know 3rd edition, 159 pages, Published by: Child Poverty Action Group ISBN 978-1-910715-05-5

Notes

- ↑ Contributions-based Jobseekers Allowance and contributions-based Employment and Support Allowance are not being replaced by Universal Credit.

References

- ↑ "Iain Duncan Smith announces the introduction of a Universal Credit". Department for Work and Pensions. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Welfare reform will restore fairness, says Duncan Smith". BBC News. 5 October 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ "2010-2015 government policy: welfare reform". gov.uk. 8 May 2015.

- 1 2 "90% of jobcentres now offer Universal Credit". Department of Work and Pensions. 22 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- 1 2 Halt universal credit or face summer of discontent, Gordon Brown tells PM The Guardian

- 1 2 Patrick Butler, Peter Walker (20 July 2018). "Universal credit falls five years behind schedule". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- 1 2 Research Briefings – Universal Credit changes from April 2016. House of Commons Library (Report). 16 November 2016. CBP7446. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ "Esther McVey tells cabinet families will lose up to £200 a month under Universal Credit". The Times. 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Butler, Patrick (3 May 2016). "Universal credit reduced to cost-cutting exercise by Treasury, say experts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Justice, The Centre for Social. "Dynamic Benefits: Towards welfare that works - The Centre for Social Justice". The Centre for Social Justice. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "Share The Facts – Transcript of speech by Iain Duncan Smith announcing Universal Credit". conservatives.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ Oborne, Peter (15 February 2015). "With Universal Credit, work might finally pay". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Ross, Tim (13 December 2012). "Universal Credit: 2 million will be better off refusing work". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Toynbee, Polly (12 July 2013). "Universal credit is simple: work more and get paid less". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Thornton, David (30 April 2011). "Universal Credit and the self employed". Universal Credit. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Wallace, Ben (14 December 2012). "OUR SYSTEM: The Universal Credit Is Not Universal | Organising For Our System". Oursystem.info. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Conditionality and sanctions" (PDF). Universal Credit: welfare that works. UK Department for Work & Pensions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-17. Retrieved 2014-07-11. Additional archives: 2013-04-02.

- ↑ Statutory Instruments 2013 No. 376, The Universal Credit Regulations 2013 Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Universal credit regulations". Disability Rights UK. 2012. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ↑ "Announcement about selection of DWP and HMRC Universal Credit sites" (PDF) (Press release). UK Department for Work & Pensions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ↑ Letter from Minister for Welfare Reform to Chairman of Local Government Association 20/2/2012

- ↑ The Register, 11 March 2013, UK's £500m web dole queue project director replaced after JUST 4 months Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Norris, Emma (21 March 2016). "What next for Universal Credit?". Institute for Government. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Malik, Shiv; Wintour, Patrick (2 August 2013). "Universal Credit staff describe chaos behind scenes of flagship Tory reform". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Shiv Malik (31 October 2013). "Universal credit: £120m could be written off to rescue welfare reform | Politics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Universal Credit – monthly experimental official statistics to 28th May 2015" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Pearce, Nick (30 April 2013). "Universal credit is trouble, but it's no welfare revolution | Comment is free". theguardian.com. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Jennifer Williams (30 April 2013). "Jobcentre staff stage protest as new benefits system rolls out". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ Third of UK’s universal credit claimants hit by deductions from payments The Observer

- ↑ Gentleman, Amelia (26 April 2013). "Universal credit pilot to launch with only a few dozen claimants". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ↑ Derek du Preez, Computerworld UK, 12 March 2013, Universal Credit calculations 'will use spreadsheets' in early rollout

- ↑ Gentleman, Amelia (29 April 2013). "Teething troubles on day one of universal credit pilot scheme". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ du Preez, Derek (11 September 2013). "Revolution comes to town with Universal Credit pilot". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "Universal Credit claimants in Pathfinder areas – experimental official statistics to September 2013" (PDF). Department for Work and Pensions. 3 December 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Payne, Sebastian (7 September 2015). "Labour defaults to Universal Credit attack at welfare questions". The Spectator (blogs). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ↑ Universal credit is in 'total disarray', says Labour Archived 15 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Revealed: universal credit sends rent arrears soaring Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Observer

- ↑ Chris Tighe, Naomi Rovnick (24 April 2018). "Food bank demand soars during universal credit rollout". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ Food bank use will soar after universal credit rollout, warns charity The Guardian

- ↑ Millions to lose £52 a week with universal credit, report shows The Observer

- ↑ Conservative rebels threaten to defeat government unless huge universal credit cuts are stopped The Independent

- ↑ "Universal credit (UC)". Disability Rights UK. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Universal Credit". GOV.UK. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Syal, Rajeev; Mason, Rowena. "Labour says universal credit will take 495 years to roll out as costs rise £3bn". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ↑ Ballard, Mark (3 June 2013). "Universal Credit will cost taxpayers £12.8bn". computerweekly.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- 1 2 Universal Credit 'could cost more than current benefits system' Archived 15 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC

- ↑ Theresa May urged to halt Universal Credit rollout Archived 26 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC

- ↑ Weaver, Matthew (29 September 2017). "Universal credit rollout should be paused, say Tory MPs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Butler, Patrick; Holmes, Matthew. "Councils fear surge in evictions as universal credit rollout accelerates". The Observer. Archived from the original on 18 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Bush, Stephen (25 October 2017). "Here's what the government is missing about Universal Credit". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ Asthana, Anushka (20 November 2017). "Ditch tax cuts to fund universal credit, says Iain Duncan Smith's thinktank". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ↑ "I’m not a criminal, but I have to commit crimes to survive": the reality of Universal Credit Archived 26 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. New Statesman

- ↑ Complex rules for universal credit see one in five claims fail Archived 13 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Observer

- ↑ People with 'nowhere else to turn' fuel rise in food bank use – study Archived 24 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Universal credit savaged by public spending watchdog Archived 15 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Universal credit IT system 'broken', whistleblowers say The Guardian

- ↑ "Major: Universal credit like 80s poll tax". BBC News. 2018-10-11. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Universal credit hits families with children hardest, study finds Archived 1 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Brewer, Mike; Finch, David; Tomlinson, Daniel (October 2017). Universal Remedy: Ensuring Universal Credit is fit for purpose (PDF). Resolution Foundation. p. 8.

- ↑ "McVey: Universal credit makes some worse off". BBC News. 2018-10-11. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Universal credit ‘penalises the self-employed’ report warns Archived 29 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Observer

- ↑ Universal credit to slash benefits for the self-employed Archived 25 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Observer

- ↑ Universal credit 'flaws' mean thousands will be worse off Archived 12 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ EDM 1908 Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Carl Packman (June 2014). Universal Credit: the problem of delay in benefit payments (PDF) (Report). Trades Union Congress (TUC). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ↑ Universal credit: MPs urge government to cut waiting time Archived 20 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC

- ↑ Universal credit: six-week wait key obstacle to its success, MPs say Archived 26 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Universal credit flaws pushing and eviction Archived 8 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ MPs launch official inquiry into universal credit as criticism grows Archived 22 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ PM will not reduce six-week wait for universal credit despite MPs’ warnings Archived 18 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Universal credit behind rising rent arrears and food bank use, 'guinea pig' councils say Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ Anti-poverty coalition calls for overhaul of universal credit The Guardian

- ↑ http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/dwp-urged-to-review-universal-credit-issues/7010917.article

- ↑ Richard Johnstone (16 February 2016). "Universal Credit will not encourage saving, IFS warns". Public Finance. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Julia Rampen (8 June 2015). "Universal Credit: 800,000 self-employed Brits could miss out on benefits". mirror. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ "Factsheet on Universal credit". cpag.org.uk. Child Poverty Action Group. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ↑ "Half a million disabled people could lose out under Universal Credit" (Press release). Citizens Advice. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Universal Credit: Disabled people 'to lose out'". BBC News. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ Julia Rampen (30 September 2015). "Desperate family loses free school meals and survives on credit cards due to Universal Credit switch – how this mum fought back". mirror. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Universal Credit hands power to abusers, MPs say BBC

- ↑ Universal credit payments at risk of being used by abusers, MPs say The Guardian

- ↑ Julia Rampen (19 February 2015). "Universal Credit rules: Domestic violence victims 'face further abuse'". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Universal credit doesn't reward hard work. It makes the most vulnerable pay Archived 1 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ A woman with no resources is a woman who can't leave: why Universal Credit is a feminist issue Archived 18 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. New Statesman

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Amelia Gentleman (13 March 2012). "Universal credit will make 150,000 single parents worse off, study finds". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- 1 2 "IDS loses legal challenge to keep Universal Credit problems secret". Politics.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Charlotte Jee (9 March 2015). "90 percent of Universal Credit staff say IT systems 'inadequate'". ComputerworldUK. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Pressure grows to make universal credit helpline free of charge Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian

- ↑ "Universal credit helpline charges to be scrapped". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017.