Kosovo Myth

The Kosovo Myth, or the Kosovo Cult (Serbian: Косовски Завет / Kosovski Zavet) is a traditional belief of the Serb people asserting that the Battle of Kosovo (June 1389) symbolizes a martyrdom of the Serbian nation in defense of their honor and Christendom against Turks (non-believers). The essence of the myth is that during the battle, Serbs, headed by Prince Lazar, lost because they consciously sacrificed the earthly kingdom (Serbian Empire) in order to gain the Kingdom of Heaven.

The legend evolved slowly through chronicles and particularly the oral tradition of Serbs. Since the 19th century period of national revivals in Europe, the Kosovo Myth became an important constitutive element of ethnic identity, as well as cultural and political homogenization of Serbs, and later of members of other South Slavic nations (Yugoslavs). The basic elements of the Kosovo Myth are vengeance, martyrdom, betrayal and glory. This myth dominated political discourse in Serbia until the end of the 20th century.[1] The Kosovo myth is incorporated into the Serb national identity's multifaceted mythomoteur.[2]

Since its establishment at the end of the 14th century, the Kosovo Myth and its poetic, literary, religious, and philosophical exposition was intertwined with political and ideological agendas.[3] The mythologization of the battle occurred shortly after the event.[4] The legend of Kosovo was not created immediately after the battle but evolved from different originators into various versions.[5] The Kosovo Myth existed in the Serbian oral tradition for centuries, until it was recorded by early collectors like Vuk Karadžić and evoked at times of later major historic events such as the Balkan Wars, the First World War[6] and by Slobodan Milošević at the end of the 1980s.[7]

The essence and basic elements of the myth

The essence of this myth is the struggle for freedom through the defense of Christianity and the establishment of the free state. Its basic elements are:[6]

- Vengeance – to restore the Serbian medieval state on the territories where it once existed

- Martyrdom – to sacrifice for freedom and faith

- Betrayal – justifies defeat and warns those who do not support the Serbian cause, such as Vuk Branković

- Glory – those who sacrifice themselves are promised "the kingdom of heaven" and eternal glory, such as Prince Lazar and Miloš Obilić

The Kosovo Myth presents the battle as "a titanic contest between Christian Europe and the Islamic East" in which Tsar Lazar renounced "the earthly kingdom for a heavenly one".[8] Although Serbia's strategic fall was the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, Kosovo was the spiritual fall of Serbia and a beginning of a new era for the Serbs. The real battle was not as decisive as presented by this myth because the final downfall of medieval Serbia happened 70 years after it, in 1459, when the Ottomans captured Smederevo.[9]

The Kosovo Myth pictures Serbia as Antemurale Christianitatis (Bulwark of Christianity), similarly to constructions of the other nations in the Balkans.[9] It is sometimes propagated to evoke a sense of pride and national grievance among Serbs.[10]

In Serbia

The scale of interpretations of the Kosovo Myth is undeniably one of the richest. It can be interpreted as "democratic, anti-feudal, with a love for justice and social equality".[11] The myth can be interpreted in different ways in connection with other myths like: myth of military valor, myth of victimhood, myth of salvation and myth of chosen people.[12]

Until 19th century

Oral epic poetry and folk songs cultivated the Kosovo Myth. Medieval church writers portrayed Prince Lazar as a servant of God whose death was martyrdom for the faith, while Serbs are portrayed as "heavenly people" who defended Christianity against Islam. Military defeat in the Kosovo Battle was portrayed as moral victory.[13] The centrality of the Kosovo Myth was one of the main causes for merging ethnic and Orthodox Christian religious identity of Serbs.[14]

Since the 19th century

The Kosovo Myth is the central myth of Serbian nationalism used since the 19th century to legitimize the intention of the Serbian nationalistic movement to create an independent national state.[15]

The Kosovo Myth was often used to create a Serbian victimization narrative.[16] This myth and its connection to the Serbian victim-centered position was used to legitimize reincorporation of Kosovo into Serbia. The Kosovo Myth was activated and linked to the metaphors of 'genocide'. Albanians from Kosovo were accused of genocide (killing and forcible expulsion) of Kosovo Serbs since the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Islamized Albanians were presented as violent and treacherous people who were settled in Kosovo to collaborate with Ottoman occupiers and terrorize Christian Serbs. This centuries-long genocide of Serbs continued in the 19th century through the forcible expulsion of up to 150,000 Serbs, and also in Tito's Yugoslavia, 'morally disqualified' Albanians to claim any control of Kosovo at the expense of Serbs.[17]

Outside of Serbia

There was a deep belief among Montenegrins that they descended from Serb knights who fled after the battle and settled in the unreachable mountains. The Kosovo Myth was present among the people in Montenegro before the time of Njegoš, in the form of folk legends and especially folk songs.[18]

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the Yugoslav idea spreading, it also became a trope in common culture of Croats and Slovenes. Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović contributed to the Kosovo Myth when in 1907–11, he was commissioned to design the Vidovdan Temple as "the eternal ideal of heroism, loyalty and sacrifice, from which our race draws its faith and moral strength" and "collective ideal of the Serbian people". The temple's actual construction on the Field of Kosovo was postponed because of the Balkan Wars, World War I, World War II, and eventually shelved. Mirko Rački, also adopted the mythos and painted numerous paintings within Kosovo cycle, including The Mother of the Jugović, Nine Jugović brothers, Kosovo Maiden and Miloš Obilić.[6]

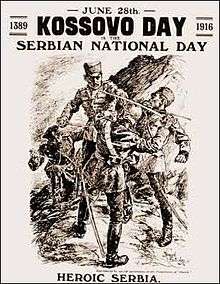

Kosovo was particularly present in the public opinion of Great Britain during the First World War where 28 June was proclaimed "Kossovo Day". Manifestations were held across the country. The Kosovo cycle epic folk poems were several times published in France during the war while some French authors emphasized that Kosovo Myth is important to strengthen "the energy for revenge".[6]

Leading up to the Kosovo War, the contemporary Kosovo Albanian political mythology clashed with the Kosovo Myth.[19]

Gazimestan

References

- ↑ Duijzings, Gerlachlus (January 2000). Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-85065-392-9.

Until recently the Kosovo myth has dominated political discourse in Serbia

- ↑ Stoianovich 1994, p. 303.

- ↑ Živković, Marko (2011). Serbian Dreambook: National Imaginary in the Time of Milošević. Indiana University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-253-22306-7.

From its very inception the myth of Kosovo and its poetic, literary, religious, and philosophical exegesis was intertwined with political agendas and ideologies....

- ↑ Milica Cimeša (28 November 2012). Marija Wakounig, ed. From Collective Memories to Intercultural Exchanges. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 78. ISBN 978-3-643-90287-0.

... the great amount of mythologization that followed shortly after it.

- ↑ Greenawalt 2001, p. 52

- 1 2 3 4 Trgovčević 1996

- ↑ Kaufman 2001, p. 205.

- ↑ Ramet 2005, p. 149.

- 1 2 Biljana Vankovska; Haken Wiberg (24 October 2003). Between Past and Future: Civil-Military Relations in Post-Communist Balkan States. I.B.Tauris. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-86064-624-9.

- ↑ Kaufman 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ Segesten 2009, p. 163.

- ↑ Segesten 2009, p. 101.

- ↑ Schnabel, Albrecht; Thakur, Ramesh Chandra (1 January 2000). Kosovo and the Challenge of Humanitarian Intervention: Selective Indignation, Collective Action, and International Citizenship. United Nations University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-92-808-1050-9.

- ↑ (Schwandner-Sievers & Fischer 2002, p. 60): "Unlike, for instance, Serbian nationalism, where ethnic and religious identities have merged (especially through the centrality of the Kosovo myth),..."

- ↑ Kaser, Karl; Katschnig-Fasch, Elisabeth (2005). Gender and Nation in South Eastern Europe. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 95. ISBN 978-3-8258-8802-2.

The myth of Kosovo is the central national myth of Serbia.

- ↑ Segesten 2009, p. 180.

- ↑ Macdonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centered Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. pp. 75, 76, 78. ISBN 978-0-7190-6467-8.

- ↑ Zirojević, Olga; Popov, Nebojša; Gojković, Drinka (January 2000). "Kosovo myth (cult) in Montenegro". The Road to War in Serbia: Trauma and Catharsis. Central European University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-963-9116-56-6.

- ↑ Vedran Obućina (2011). "A War of Myths: Creation of the Founding Myth of Kosovo Albanians". Contemporary issues. 4/1: 41.

Contemporary Albanian political mythology is very similar in power, focus and methods to Serbian political mythology about Kosovo. Combined, they make a powerful clash point, a war of the myths which ended in violence and armed conflict. The Albanian myth prevailed.

Sources

- Stoianovich, Traian (1994). Balkan Worlds: The First and Last Europe. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3851-9.

- Trgovčević, Ljubinka (1996), "The Kosovo Myth in the First World War", in Konev, Ilija, Sveti mesta na Balkanite, Blagoevgrad: UNESCO, pp. 331–338, ISBN 9789548317429, OCLC 52405733

- Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8736-1.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (8 December 2005). Thinking about Yugoslavia: Scholarly Debates about the Yugoslav Breakup and the Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61690-4.

- Segesten, Anamaria Dutceac (2009). Myth, Identity and Conflict: A Comparative Analysis of Romanian and Serbian Textbooks. ProQuest. ISBN 978-1-109-19838-6.

Further reading

- Greenawalt, Alexander (2001). "Kosovo Myths: Karadžić, Njegoš, and the Transformation of Serb Memory" (pdf). Spaces of identity. 3: 51. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Konstantinović, Zoran (27–29 May 2005). "КОСОВСКИ КУЛТ У САВРЕМЕНОМ СРПСКОМ МЕНТАЛИТЕТУ" (PDF). СРБИ НА КОСОВУ И У МЕТОХИЈИ. SANU.

- Prošić-Dvornić, Mirjana (1992). "Изложба Косовска легенда y народном стваралаштву". Гласник Етнографског музеја, књ. 56.

- Rakić, Radomir (1989). "Kosovo srpske nacije (etno-politikološki ogled)" (PDF). Etnološke sveske. 10: 5–46.

- Spasić, Ivana (2015). "The trauma of Kosovo in Serbian national narratives". Narrating Trauma: On the Impact of Collective Suffering. Routledge. pp. 81–106.

- Trebješanin, Žarko (1989). "ZNAČAJ KOSOVSKOG MITA ZA SOCIJALIZACIJU U SRPSKOJ PATRIJARHALNOJ KULTURI" (PDF). Etnološke sveske. 10: 113–117.

- Vučetić, J. (2011). "Kosovo myth in the poetry of Đura Jakšić" (PDF). Baština (31): 87–100.

- Zurovac, Mirko (27–29 May 2005). "ЛУЧА КОСОВСКОГ МИТА" (PDF). СРБИ НА КОСОВУ И У МЕТОХИЈИ. SANU.

- Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (2002). Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34189-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Kosovo. |