Ketorolac

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Toradol, Acular, Sprix, others |

| Synonyms | ketorolac tromethamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a693001 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, I.M., I.V., intranasal, ocular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (All routes) |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life |

3.5 h to 9.2 h, young adults; 4.7 h to 8.6 h, elderly (mean age 72) |

| Excretion |

Kidney: 91.4% (mean) Biliary: 6.1% (mean) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.110.314 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

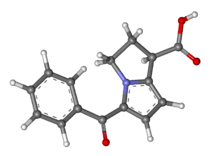

| Formula | C15H13NO3 |

| Molar mass | 255.27 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Ketorolac, sold under the brand name Toradol among others, is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in the family of heterocyclic acetic acid derivatives, used as an analgesic.[1][2][3] It is considered a first-generation NSAID.[4]

Ketorolac acts by inhibiting the bodily synthesis of prostaglandins. Ketorolac in its oral (tablet or capsule) and intramuscular (injected) preparations is a racemic mixture of both (S)-(−)-ketorolac, the active isomer, and (R)-(+)-ketorolac.[4]

Ketorolac was developed in 1989 by Syntex Corp. (now part of Roche).[5] It was approved for medical use in the United States in 1989.[6] The eye-drop formulation was approved by the FDA in 1992.[7] An intranasal formulation was approved by the FDA in 2010[8] for short-term management of moderate to moderately severe pain requiring analgesia at the opioid level. As of 2015, the cost for a typical course of medication in the United States is less than US$25.[9]

Medical uses

Ketorolac is used for short-term management of moderate to severe pain[10]. It is usually not prescribed for longer than five days.[2][3][11][12] Ketorolac is effective when administered with paracetamol to control pain in neonates because it does not depress respiration as do opioids.[13] Ketorolac is also an adjuvant to opioid medications and improves pain relief. It is also used to treat dysmenorrhea.[12] Ketorolac is used to treat idiopathic pericarditis, where it reduces inflammation.[14]

Ketorolac is used for short-term pain control not lasting longer than five days, and can be administered orally, by intramuscular injection, intravenously, and by nasal spray.[2] Ketorolac is initially administered by intramuscular injection or intravenously[15]. Oral therapy is only used as a continuation from the intramuscular or intravenous starting point.[2][13]

Ketorolac is used during eye surgery to maintain mydriasis, or the 'relaxing' of the iris muscles that will allow surgeons to perform cataract surgery.[16] Ketorolac is effective in treating ocular itching.[17] The ketorolac ophthalmic formulation is associated with a decreased development of macular edema after cataract surgery and is more effective alone rather than as an opioid/ketorolac combination treatment.[18][19] Ketorolac has also been used to manage pain from corneal abrasions.[20]

During treatment with ketorolac, clinicians monitor for the manifestation of adverse effects and side effects. Lab tests, such as liver function tests, bleeding time, BUN, serum creatinine and electrolyte levels are often used and help to identify potential complications.[2][3]

Contraindications

Ketorolac is contraindicated in those with hypersensitivity, allergies to the medication, cross-sensitivity to other NSAIDs, prior to surgery, history of peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, alcohol intolerance, renal impairment, cerebrovascular bleeding, nasal polyps, angioedema, and asthma.[2][3] Recommendations exist for cautious use of ketorolac in those who have experienced cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, coagulation disorders, renal impairment, and hepatic impairment.[2][3]

Adverse effects

Though uncommon, potentially fatal adverse effects are stroke, myocardial infarction, GI bleeding, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and anaphylaxis. A less serious and more common (>10%) side effect is drowsiness. Infrequent (<1%) side effects are paresthesia, prolonged bleeding time, injection site pain, purpura, sweating, abnormal thinking, increased production of tears, edema, pallor, dry mouth, abnormal taste, urinary frequency, increased liver enzymes, itching and others. Ketorolac can cause premature constriction of the ductus arteriosis in an infant during the third trimester of pregnancy.[2][3] Platelet function is decreased related to the use of ketorolac.[4]

The practice of restricting treatment with ketorolac is due to its potential to cause kidney damage.[21]

Interactions

Ketorolac can interact with other medications. Probenecid can increase the probability of having an adverse reaction or experiencing a side effect when taken with ketorolac. Pentoxifylline can increase the risk of bleeding. When aspirin is taken at the same time as ketorolac, the effectiveness is decreased. Problematic GI effects are additive and become more likely if potassium supplements, aspirin, other NSAIDS, corticosteroids, or alcohol is taken at the same time. The effectiveness of antihypertensives and diuretics can be lowered. The use of ketorolac can increase serum lithium levels to the point of toxicity. Toxicity to methotrexate is more likely if ketorolac is taken at the same time. The risk of bleeding increases with the concurrent medications clopidogrel, cefoperazone, valproic acid, cefotetan, eptifibatide, tirofiban, and copidine. Anticoagulants and thrombolytic medications also increase the likelihood of bleeding. Medications used to treat cancer can interact with ketorolac along with radiation therapy. The risk of toxicity to the kidneys increases when ketorolac is taken with cyclosporine.[2][3]

Interactions with ketorolac exist with some herbal supplements. Panax ginseng, clove, ginger, arnica, feverfew, dong quai, chamomile, and Ginkgo biloba, increases the risk of bleeding.[2][3]

Mechanism of action

The primary mechanism of action responsible for ketorolac's anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic effects is the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by competitive blocking of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX). Ketorolac is a non-selective COX inhibitor.[22] Ketorolac has been assessed to be a relatively higher risk NSAID when compared to aceclofenac, celecoxib, and ibuprofen.[14]

History

In the US, ketorolac was the only widely available intravenous NSAID for many years; an IV form of paracetemol, which is not an NSAID, became available in Europe in 2009 and then in the US.[13]

The Syntex company, of Palo Alto, California developed the ophthalmic solution Acular around 2006.

In 2007, there were concerns about the high incidence of reported side effects. This led to restriction in its dosage and maximum duration of use. In the UK, treatment was initiated only in a hospital, although this was not designed to exclude its use in prehospital care and mountain rescue settings[23]. Dosing guidelines were published at that time.[24]

Concerns over the high incidence of reported side effects with ketorolac trometamol led to its withdrawal (apart from the ophthalmic formulation) in several countries, while in others its permitted dosage and maximum duration of treatment have been reduced. From 1990 to 1993, 97 reactions with a fatal outcome were reported worldwide.[25]

References

- ↑ Mallinson, Tom (2017). "A review of ketorolac as a prehospital analgesic". Journal of Paramedic Practice. London: MA Healthcare. 9 (12): 522–526. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Vallerand, April H. (2017). Davis's Drug Guide for Nurses. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. p. 730. ISBN 9780803657052.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Physician's Desk Reference 2017. Montvale, New Jersey: PDR, LLC. 2017. pp. S–474–5. ISBN 9781563638381.

- 1 2 3 Henry, p. 279.

- ↑ "History of Roche Bioscience – FundingUniverse". Fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ↑ "Ketorolac medical facts from". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ↑ "Ketorolac ophthalmic medical facts from". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ↑ "Sprix Information from". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 9. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Mallinson, Tom (2017). "A review of ketorolac as a prehospital analgesic". Journal of Paramedic Practice. London: MA Healthcare. 9 (12): 522–526. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ↑ "Ketorolac-tromethamine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- 1 2 Henry, p. 291.

- 1 2 3 Martin, Lizabeth D; Jimenez, Nathalia; Lynn, Anne M (2017). "A review of perioperative anesthesia and analgesia for infants: updates and trends to watch". F1000Research. 6: 120. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10272.1. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 5302152. PMID 28232869.

- 1 2 Schwier, Nicholas; Tran, Nicole (2016). "Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Aspirin Therapy for the Treatment of Acute and Recurrent Idiopathic Pericarditis". Pharmaceuticals. 9 (2): 17. doi:10.3390/ph9020017. ISSN 1424-8247.

- ↑ Mallinson, Tom (2017). "A review of ketorolac as a prehospital analgesic". Journal of Paramedic Practice. London: MA Healthcare. 9 (12): 522–526. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ↑ Saenz-de-Viteri, Manuel; Gonzalez-Salinas, Roberto; Guarnieri, Adriano; Guiaro-Navarro, María Concepción (2016). "Patient considerations in cataract surgery – the role of combined therapy using phenylephrine and ketorolac". Patient Preference and Adherence. Volume 10: 1795–1801. doi:10.2147/PPA.S90468. ISSN 1177-889X.

- ↑ Karch, Amy (2017). Focus on nursing pharmacology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. p. 272. ISBN 9781496318213.

- ↑ Lim, Blanche X; Lim, Chris HL; Lim, Dawn K; Evans, Jennifer R; Bunce, Catey; Wormald, Richard; Wormald, Richard (2016). "Prophylactic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of macular oedema after cataract surgery". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11: CD006683. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006683.pub3. PMID 27801522.

- ↑ Sivaprasad, Sobha; Bunce, Catey; Crosby-Nwaobi, Roxanne; Sivaprasad, Sobha (2012). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents for treating cystoid macular oedema following cataract surgery". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004239. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004239.pub3. PMID 22336801.

- ↑ Wakai A, Lawrenson JG, Lawrenson AL, Wang Y, Brown MD, Quirke M, Ghandour O, McCormick R, Walsh CD, Amayem A, Lang E, Harrison N (2017). "Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5: CD009781. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009781.pub2. PMID 28516471.

- ↑ Henry, p. 280.

- ↑ Lee, I. O.; Seo, Y. (2008). "The Effects of Intrathecal Cyclooxygenase-1, Cyclooxygenase-2, or Nonselective Inhibitors on Pain Behavior and Spinal Fos-Like Immunoreactivity". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 106 (3): 972–977, table 977 contents. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e318163f602. PMID 18292448.

- ↑ Mallinson, Tom (2017). "A review of ketorolac as a prehospital analgesic". Journal of Paramedic Practice. London: MA Healthcare. 9 (12): 522–526. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ↑ MHRA Drug Safety Update October 2007, Volume 1, Issue 3, pp 3-4.

- ↑ Committee on the Safety of Medicines, Medicines Control Agency: Ketorolac: new restrictions on dose and duration of treatment. Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance: June 1993; Volume 19 (pages 5-8).

Bibliography

- AHFS drug information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2011. ISBN 9781585282609.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 9. ISBN 9781284057560.

- Handley, Dean A.; Cervoni, Peter; McCray, John E.; McCullough, John R. (1998). "Preclinical enantioselective pharmacology of (R)- and (S)- ketorolac". J Clin Pharmacol. 38 (2 Suppl): 25S–35S. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04414.x. ISSN 0091-2700. PMID 9549656.

- Henry, Norma (2016). RN pharmacology for nursing : review module. Overland Park, KS: Assessment Technologies Institute. ISBN 9781565335738.

- Kizior, Robert (2017). Saunders nursing drug handbook 2017. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. ISBN 9780323442916.

External links

- cme.medscape.com on nasal ketorolac, accessed March 30, 2017