Coinage of India

Coinage of India, issued by imperial dynasties and middle kingdoms, began anywhere between the 1st millennium BCE to the 6th century BCE, and consisted mainly of copper and silver coins in its initial stage.[1] Scholars remain divided over the origins of Indian coinage.[2]

Cowry shells was first used in India as commodity money.[3] The Indus Valley Civilization dates back between 2500 BCE and 1750 BCE.[4] What is known, however, is that metal currency was minted in India well before the Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE),[5] and as radio carbon dating indicates, before the 5th century BCE.[6]

The practice of minted coins spread to the Indo-Gangetic Plain from West Asia. The coins of this period were called Puranas, Karshapanas or Pana.[7] These earliest Indian coins, however, are unlike those circulated in West Asia, were not disk-shaped but rather stamped bars of metal, suggesting that the innovation of stamped currency was added to a pre-existing form of token currency which had already been present in the Mahajanapada kingdoms of the Indian Iron Age. Mahajanapadas that minted their own coins included Gandhara, Kuntala, Kuru, Panchala, Shakya, Surasena and Surashtra.[8]

The tradition of Indian coinage was further influenced by the coming of Turkic and Mughal invaders in India.[1] The East India Company introduced uniform coinage in the 19th century CE, and these coins were later imitated by the modern nation states of Republic of India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh.[9] Numismatics plays a valuable role in determining certain period of Indian history.[9]

Maha Janapadas period (600 BCE – 300 BCE)

Indian Punched mark Karshapana coins

India developed some of the world's first coins, but scholars debate exactly which coin was first and when. Sometime around 600BC in the lower Ganges valley in eastern India a coin called a punchmarked Karshapana was created[10][11]. According to Hardaker, T.R. the origin of Indian coins can be placed at 575 BCE[12] and according to Gupta in the seventh century BCE.

Punch-marked coins were a type of early Coinage of India, dating to between about the 6th and 2nd centuries BCE. There are actually vast uncertainties regarding the actual time punch-marked coinage started in India, with proposal ranging from 1000 BCE to 500 BCE.[13] However, the study of the relative chronology of these coins has successfully established that the first punch-marked coins initially only had one or two punches, with the number of punches increasing over time.[13]

The first coins in India may have been minted around the 6th century BCE by the Mahajanapadas of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, The coins of this period were punch-marked coins called Puranas, Karshapanas or Pana. Several of these coins had a single symbol, for example, Saurashtra had a humped bull, and Dakshin Panchala had a Swastika, others, like Magadha, had several symbols. These coins were made of silver of a standard weight but with an irregular shape. This was gained by cutting up silver bars and then making the correct weight by cutting the edges of the coin.[14]

They are mentioned in the Manu, Panini, and Buddhist Jataka stories and lasted three centuries longer in the south than the north (600 BCE – 300 CE).[15]

Early coins of India (400 BCE – 100 CE) were made of silver and copper, and bore animal and plant symbols on them.[1]

_circa_350-315_BCE.jpg)

Saurashtra die struck Quarter Karshapana coins

Saurashtra Janapada coins are probably the earliest die-struck figurative coins from ancient India from 450-300 BCE which are also perhaps the earliest source of Hindu representational forms. Most coins from Surashtra are approximately 1g in weight. Rajgor believes they are therefore quarter karshapanas of 8 rattis, or 0.93 gm. Mashakas of 2 rattis and double mashakas of 4 rattis are also known.

The coins appear to be uniface, in that there is a single die-struck symbol on one side. However, most of the coins appear to be overstruck over other Surashtra coins and thus there is often the remnant of a previous symbol on the reverse, as well as sometimes under the obverse symbol as well[17].

Greek and Achaemenid coinage in northwestern India

Coin finds in the Chaman Hazouri hoard in Kabul or the Shaikhan Dehri hoard in Pushkalavati have revealed numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE were circulating in the area, at least as far as the Indus during the reign of the Achaemenids, who were in control of the areas as far as Gandhara.[21][22][19][23] In 2007 a small coin hoard was discovered at the site of ancient Pushkalavati (Shaikhan Dehri) in Pakistan. The hoard contained a tetradrachm minted in Athens circa 500/490-485/0 BCE, together with a number of local types as well as silver cast ingots. The Athens coin is the earliest known example of its type to be found so far to the east.[24]

According to Joe Cribb, these early Greek coins were at the origin of Indian punch-marked coins, the earliest coins developed in India, which used minting technology derived from Greek coinage.[19] Daniel Schlumberger also considers that punch-marked bars, similar to the many punch-marked bars found in northwestern India, initially originated in the Achaemenid Empire, rather than in the Indian heartland:

“The punch-marked bars were up to now considered to be Indian (...) However the weight standard is considered by some expert to be Persian, and now that we see them also being uncovered in the soil of Afghanistan, we must take into account the possibility that their country of origin should not be sought beyond the Indus, but rather in the oriental provinces of the Achaemenid Empire"

Classical period (300 BCE – 1100 CE)

Coins of the Mauryas

The Mauryan Empire coins were punch marked with the royal standard to ascertain their authenticity.[25] The Arthashastra, written by Kautilya, mentions minting of coins but also indicates that the violation of the Imperial Maurya standards by private enterprises may have been an offence.[25] Kautilya also seemed to advocate a theory of bimetallism for coinage, which involved the use of two metals, copper and silver, under one government.[26]

| Maurya Empire coinage |

|

Popularity of cast die-struck coins (end of 3rd century BCE)

Punch marked coins were replaced at the fall of the Maurya Empire by cast, die-struck coins.[28] Each individual coins was first cast by pouring a molten metal, usually copper or silver, into a cavity formed by two molds. These were then usually die-struck while still hot, first on just one side, and then later on the two sides. The coin devices are Indian, but it is thought that this coin technology was introduced from the West, either from the Achaemenid Empire or from the neighboring Greco-Bactrian kingdom.[29]

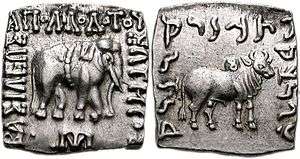

Coins of the Indo-Greeks

Obv: Helmetted, diademed and draped bust of Philoxenus. Greek legend BASILEOS ANIKETOU PHILOXENOU "Of the Invincible King Philoxenus"

Rev: King on prancing horse in military dress. Kharoshti legend MAHARAJASA APADIHATASA PHILASINASA "Undefeatable King Philoxenus".

The Indo-Greek kings introduced Greek types, and among them the portrait head, into the Indian coinage, and their example was followed for eight centuries.[30] Every coin has some mark of authority in it, this is what known as "types". It appears on every Greek and Roman coin.[30] Demetrios was the first Bactrian king to strike square copper coins of the Indian type, with a legend in Greek on the obverse, and in Kharoshthi on the reverse.[30] Copper coins, square for the most part, are very numerous. The devices are almost entirely Greek, and must have been engraved by Greeks, or Indians trained in the Greek traditions. The rare gold staters and the splendid tetradrachms of Bactria disappear.[30] The silver coins of the Indo-Greeks, as these later princes may conveniently be called, are the didrachm and the hemidrachm. With the exception of certain square hemidrachms of Apollodotos and Philoxenos, they are all round, are struck to the Persian (or Indian) standard, and all have inscriptions in both Greek and Kharoshthi characters.[30]

Coinage of Indo-Greek kingdom began to increasingly influence coins from other regions of India by the 1st century BCE.[1] By this time a large number of tribes, dynasties and kingdoms began issuing their coins; Prākrit legends began to appear.[1] The extensive coinage of the Kushan empire (1st–3rd centuries CE) continued to influence the coinage of the Guptas (320 to 550 CE) and the later rulers of Kashmir.[1]

During the early rise of Roman trade with India up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India.[31] Gold coins, used for this trade, was apparently being recycled by the Kushan empire for their own coinage. In the 1st century CE, the Roman writer Pliny the Elder complained about the vast sums of money leaving the Roman empire for India:

| “ | India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what percentage of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead? - Pliny, Historia Naturalis 12.41.84. | ” |

The trade was particularly focused around the regions of Gujarat, ruled by the Western Satraps, and the tip of the Indian peninsular in Southern India. Large hoards of Roman coins have been found and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of South India.[32] The South Indian kings reissued Roman-like coinage in their own name, either producing their own copies or defacing real ones in order to signify their sovereignty.[33]

Coins of the Sakas and the Pahlavas (200 BCE – 400 CE)

During the Indo-Scythians period whose era begins from 200 BCE to 400 CE, a new kind of the coins of two dynasties were very popular in circulation in various parts of the then India and parts of central and northern South Asia (Sogdiana, Bactria, Arachosia, Gandhara, Sindh, Kashmir, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar).[30] These dynasties were Saka and The Pahlavas.After the conquest of Bactria by the Sakas in 135 BCE there must have been considerable intercourse sometimes of a friendly, sometimes of a hostile character, between them and the Parthians, who occupied the neighboring territory.[30]

Maues, whose coins are found only in the Punjab, was the first king of what may be called the Azes group of princes. His silver is not plentiful; the finest type is that with a "biga" (two-horsed chariot) on the obverse, and this type belongs to a square Hemi drachm, the only square aka silver coin known. His most common copper coins, with an elephant's head on the obverse and a "Caduceus" (staff of the god Hermes) on the reverse are imitated from a round copper coin of Demetrius. On another copper square coin of Maues the king is represented on horseback. This striking device is characteristic both of the Saka and Pahlava coinage; it first appears in a slightly different form on coins of the Indo-Greek Hippostratos; the Gupta kings adopted it for their "horseman" type, and it reappears in Medieval India on the coins of numerous Hindu kingdoms until the 14th century CE.[30]

Coins of Kanishka and Huvishka (100 CE – 200 CE)

Kanishka's copper coinage which came into the scene during 100–200 CE was of two types: one had the usual "standing king" obverse, and on the rarer second type the king is sitting on a throne. At about the same time there was Huvishka's copper coinage which was more varied; on the reverse, as on Kanishka's copper, there was always one of the numerous deities; on the obverse the king was portrayed (1) riding on an elephant, or (2) reclining on a couch, or (3) seated cross-legged, or (4) seated with arms raised.

Coinage of the Guptas Empire (320 CE – 480 CE)

The Gupta Empire produced large numbers of gold coins depicting the Gupta kings performing various rituals, as well as silver coins clearly influenced by those of the earlier Western Satraps by Chandragupta II.[1]

The splendid gold coinage of Guptas, with its many types and infinite varieties and its inscriptions in Sanskrit, are the finest examples of the purely Indian art that we possess.[30] Their era starts from around 320 with Chandragupta I's accession to the throne.[30]Son of Chandragupta I-Samudragupta, the real founder of the Gupta Empire had coinage made of gold only.[30] There were seven different varieties of coins that appeared during his reign.[30] Out of them the archer type is the most common and characteristic type of the Gupta dynasty coins, which were struck by at least eight succeeding kings and was a standard type in the kingdom.[30]

The silver coinage of Guptas starts with the overthrow of the Western Satraps by Chandragupta II. Kumaragupta and Skandagupta continued with the old type of coins (the Garuda and the Peacock types) and also introduced some other new types.[30] The copper coinage was mostly confined to the era of Chandragupta II and was more original in design. Eight out of the nine types known to have been struck by him have a figure of Garuda and the name of the King on it. The gradual deterioration in design and execution of the gold coins and the disappearance of silver money, bear ample evidence to their curtailed territory.[30] The percentage of gold in Indian coins under the reign of Gupta rulers showed a steady financial decline over the centuries as it decreases from 90% pure gold under Chandragupta I (319-335) to a mere 75-80% under Skandagupta (467).

Coinage of the Rajputs (900 CE – 1400 CE)

The coins of various Rajput princes's ruling in Hindustan and Central India were usually of gold, copper or billon, very rarely silver. These coins had the familiar goddess of wealth, Lakshmi on the obverse. In these coins, the Goddess was shown with four arms than the usual two arms of the Gupta coins; the reverse carried the Nagari legend. The seated bull and horseman were almost invariable devices on Rajput copper and bullion coins.[30]

Late Middle Ages – contemporary history (1300 CE – 2000 CE)

The Alf Coins of King Akbar (1582 CE – 1610 CE)

Political orders in Medieval India were based on a relationship and association of power by which the supreme ruler, especially a monarch was able to influence the actions of the subjects.[35]

In order for the relationship to work, it had to be expressed and communicated in the best possible way. In other words, power was by nature declarative from the point of view of its intelligibility and comprehensibility to the audience and required modes of communication to take effect by means of which sovereign power was articulated in the 16th century India.[35]

An examination was done of a series of coins officially issued and circulated by the Mughal emperor Akbar (r 1556-1605) to illustrate and project a particular view of time, religion, and political supremacy being fundamental and co-existing in nature.

Coins constitute part of the evidence that project the transmission of religious and political ideas in the last quarter of the 16th century.

The word 'Alf' refers to the millennium.[35] The following are the extraordinary decisions, though bizarre, were taken by King Akbar.

- The date in coins were written in words and not in figures.

- If the intention was to refer to the year 1000 (yak hazar) of the Islamic calendar (hijri era) as is traditionally believed, the expression adopted for it (Alf) was unorthodox and eccentric.

- Akbar, ultimately and more importantly, commanded Alf to be imprinted on the coins in 990 hijri (1582 CE ), or ten years before the date (1000 hijri) was due.

The order was a major departure and extremely unconventional and eccentric from the norm of striking coins in medieval India. Till the advent of Alf, all gold and silver coins had been stuck with figure of the current hijri year.[35]

Akbar's courtier and critic, Abdul Badani, presents and explains in brevity the motive for these unconventional decisions while describing the events that took place in 990 hijri (1582 CE):

And having thus convinced himself that the thousand years from the prophethood of the apostle (B'isat I Paighambar) the duration for which Islam [lit. religion] would last was now over, and nothing prevented him from articulating the desires he so secretly held in his heart, and the space became empty of the theologians (ulema) and mystics (mashaikh) who had carried awe and dignity and no need was felt for them: he [Akbar] felt himself at liberty to refute the principles of Islam and to institute new regulations, obsolete and corrupt but considered precious by his pernicious beliefs. The first order, which was given to write the date Alf on coins (Dar Sikka tank half Navisand) and to write the Tarikh-i-Alfi [history of the millennium] from the demise (Rihlat) of the prophet (Badauni II: 301).[35]

The evidence, both textual and numismatic, actually makes it clear that Akbar's decisions to mint the Alf coins and commission the Tarikh-i-Alfi were based on a new communication and interpretation of the terminal dates of the Islamic millennium.

What the evidence doesn't explain is the source of the idea as well as the reason for persisting with the same date on the imperial coinage even after the critical year had passed.[35]

Gallery

Queen Kumaradevi and King Chandragupta I on a coin of their son Samudragupta 380 CE.

Queen Kumaradevi and King Chandragupta I on a coin of their son Samudragupta 380 CE. Gold coin of Gupta era, depicting a Gupta king holding a bow, 300 CE.

Gold coin of Gupta era, depicting a Gupta king holding a bow, 300 CE. Maratha Empire, Chhatrapati Shivaji, Gold hon, c. 1674–80 CE.

Maratha Empire, Chhatrapati Shivaji, Gold hon, c. 1674–80 CE. Silver Rupee coin of Rudra Simha of Ahom kingdom, 1696 CE.

Silver Rupee coin of Rudra Simha of Ahom kingdom, 1696 CE. Maratha Kingdom of Baroda, Sayaji Rao III, 1870 CE.

Maratha Kingdom of Baroda, Sayaji Rao III, 1870 CE.- Gold coin of Raja Raja Chola I, 985–1014 CE.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Allan & Stern (2008)

- ↑ Dhavalikar (1975)

- ↑ Kramer, History Begins at Sumer, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ https://www.rbi.org.in/currency/museum/c-ancient.html

- ↑ Sellwood (2008)

- ↑ Dhavalikar, M. K. (1975), "The beginning of coinage in India", World Archaeology, 6 (3): 330-338, Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

- ↑ See P.L. Gupta: Coins, New Delhi, National Book Trust, 1996, Chapter II.

- ↑ "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Gandhara Janapada". Coinindia.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22. "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Kuntala Janapada". Coinindia.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22. "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Kuru Janapada". Coinindia.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22. "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Panchala Janapada". Coinindia.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22. "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Shakya Janapada". Coinindia.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22. "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Shurasena Janapada". Coinindia.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2012-05-22. "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Surashtra Janapada". Coinindia.com. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- 1 2 Sutherland (2008)

- ↑ Anderson, Joel. "Coins of India from ancient times to the present". www.joelscoins.com. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- ↑ Cunningham, Alexander (December 1996). Coins of Ancient India: From the Earliest Times Down to the Seventh Century A. D. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120606067.

- ↑ HARDAKER, TERRY R. (1975). "The origins of coinage in northern India". The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-). 15: 200–203.

- 1 2 Cribb, Joe. Investigating the introduction of coinage in India- a review of recent research, Journal of the Numismatic Society of India xlv (Varanasi 1983), pp.95-101. pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Śrīrāma Goyala (1994). The Coinage of Ancient India. Kusumanjali Prakashan.

- ↑ "Puranas or Punch-Marked Coins (circa 600 BC – circa 300 AD)". Government Museum Chhennai. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ↑ http://coinindia.com/galleries-surashtra.html Accessed 06/03/2007

- ↑ "The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Surashtra Janapada". coinindia.com. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- 1 2 3 Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780951839911.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. pp. 300–301.

- ↑ US Department of Defense

- 1 2 Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. pp. 308-.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- 1 2 Prasad, 168

- ↑ Prasad, 166

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History Book Review Trust, New Delhi, Popular Prakashan, 1995, p.151

- ↑ The Coins Of India, by Brown, C.J. p.13-20

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Brown C.J (1992)

- ↑ "The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917".

- ↑ Curtin, 100

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund, 108

- ↑ The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans, by John M. Rosenfield, University of California Press, 1967 p.135

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Himanshu, P. R. (2006)

References

- Himanshu Prabha Ray (2006), "Coins in India", ISBN 81-85026-73-4.

- Allan, J. & Stern, S. M. (2008), coin, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Agrawal, Ashvini (1989), Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0592-5.

- Chaudhuri, K. N. (1985), Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-28542-9.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond etc. (1984), Cross-Cultural Trade in World History, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26931-8.

- Dhavalikar, M. K. (1975), "The beginning of coinage in India", World Archaeology, 6 (3): 330-338, Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

- Kulke, Hermann & Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32919-1.

- Prasad, P.C. (2003), Foreign trade and commerce in ancient India, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-053-2.

- Sellwood, D. G. J. (2008), coin, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Srivastava, A.L. & Alam, Muzaffar (2008), India, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Sutherland, C. H. V. (2008), coin, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Himanshu, P. R. (2006), Coins in India:Power and Communication, J.J. Bhabha Marg Publication, ISBN 81-85026-73-4.

- Brown, C.J. (1992), The Coins of India, Association Press(Y.M.C.A), ISBN 978-81-8090-192-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coins of India. |

- British India Coins Wiki

- Persian & Devanagari Legends on Silver Rupees of India

- India Coin News & Forums

- Indian Coins Encyclopedia

- Reserve Bank of India Monetary Museum (RBI)

- Oriental Coins Database at Zeno.ru

- Indian Coins-Numismatics Forum - Coins of India

- CoinIndia: The Virtual Museum of Indian Coins