Chera dynasty

| Chera kingdom | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 3rd century BCE–12th century CE | |||||||||||

| Status | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| Common languages | Tamil | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | c. 3rd century BCE | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 12th century CE | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| History of Tamil Nadu |

|---|

|

The Chera dynasty were one of the principal dynasties in the early history of the present day states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu in South India. Along with the Ay kingdom in the south and the Ezhimala kingdom in the north, they formed the ruling kingdoms of Kerala in the early years of the Common Era (CE or AD).[1] Together with the Cholas and the Pandyas, they were known as one of the three major political powers of ancient Tamilakam in Tamil Nadu in the early centuries of the Common Era.[2]

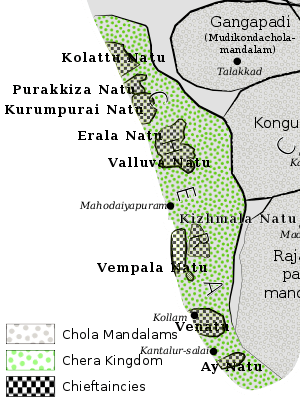

The age and antiquity of the Cheras is difficult to establish.[3] The Early Cheras are known to have established capitals at various locations around Karur, Muziris and Tyndis among others. The 'Irumporai' Cheras and the 'Kongu' Cheras are also known to have controlled Karur in central Tamil Nadu at various points in time.[4] The Cheras of Makotai (modern Kodungallur, Kerala) were also known as the Kulasekharas or the Perumals, and were in power between c. 8th and 12th century in Kerala.[5] The exact nature of the relationships between the various lines of Chera rulers is somewhat unclear.[4]

Most of the ancient Chera history is reconstructed from a body of bardic collection known as the Sangam (the Academy) literature. Other sources for the early Cheras include inscriptions, the royal edicts of Ashoka, coins, and accounts by Graeco-Roman writers. The Sangam poems record the names of a long line of Chera rulers, and the poets who extolled them. The internal chronology of this collection is still far from completely settled and a connected account of the history of the period is an area of active research. Utiyan Cheral, Nedum Cheral Atan and Cenguttuvan are some of the rulers referred to in the Sangam poems. Cenguttuvan, the most celebrated of the Cheras, is famous for the legends surrounding Kannaki, the heroine of the Tamil epic Cilapatikaram.[6][4]

The Chera kingdom owed its importance to "trade" with the Middle East and the Graeco-Roman world. Its geographical advantages, like the presence of a large number of rivers connecting the Ghat mountains with the Arabian sea, the favourable Monsoon winds which carried sailing ships directly from the Arabian coast to Kerala as well as the abundance of exotic spices in the mountains combined to make the Cheras a major power in ancient South India.[7]

It is understood that the early Cheras started their imperial expansion from the wider Kuttanad region, which included areas around Vembanad lake.[8] Various other regions such as Tyndis and Kongunad have been gained or lost at various times during the continuous conflicts with the neighbouring kingdoms in modern-day Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The Cheras fought regular battles with other neighbouring kingdoms such as the Cholas, Pandyas, Pallavas, Rashtrakutas, the Kadambas and even with the Yavanas (the Greeks) on the South Indian coast. After the end of the Sangam era, around the 5th century CE, there seems to be a period where the Cheras' power declined and is, in many ways, a dark period in Chera history.

It is understood that in the 12th century, they moved their capital further south to Kollam from Kodungallur (or Makotai) following a series of wars with the Cholas.[9] The rulers of Venadu, based out of the port of Kollam in southern Kerala, traced their ancestry to the Cheras of Makotai. Ravi Varma Kulasekhara, their most ambitious ruler, set out to expand his kingdom by annexing the ruins of the other southern kingdoms.[10] In the modern period also the rulers of Cochin and Trivandrum claimed the title "Chera".[5]

Etymology

The etymology of ""Chera"" is still a matter of considerable speculation. One approach proposes that the word is derived from Cheral, a corruption of Charal meaning "declivity of a mountain" in Tamil, suggesting a connection with the mountainous geography of Kerala. Another links the words to Kera, a root word for the coconut, one of the primary products of the land. Another theory argues that the Keralam and Cheralam are derived from cher (sand) and alam (region), literally meaning, "the slushy land".[lower-alpha 1] This compound could also be interpreted to mean "the land which was added on" (to the existing mountainous or hilly country) as Cher or Chernta means "added".[lower-alpha 2]

In other sources, the Cheras are referred to by various names. The Cheras are referred as Kedalaputo (Sanskrit: "Kerala Putra") in the Emperor Ashoka's Pali edicts (3rd century BCE).[13] While Pliny the Elder and Claudius Ptolemy refer to the Cheras as Kaelobotros and Kerobottros respectively, the Graeco-Roman trade map Periplus Maris Erythraei refers to the Cheras as Keprobotras.[14]

The term Ceralamdivu or Ceran tivu and its cognates, meaning the "island of the Ceran kings", is a Classical Tamil name of Sri Lanka that takes root from the term Chera, from which the dynasty name is derived.[15]

History

Early Cheras

The earliest Graeco-Roman accounts referring to the Cheras are by Pliny the Elder in the 1st century CE, in the periplus of the 1st century CE, and by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE. [16]

One of the earliest Sanskrit works which refers to the Cheras is probably the Aitareya Aranyaka in which the Cherapadah are noted as one of the three peoples who did not follow some ancient injunctions. There are also brief references by Katyayana (4th century BCE), Patanjali (2nd century BCE) and Kautilya (c. 4th century BCE) though Panini (5th century BCE) does not mention the land.[17]

However, it is the Tamil works collectively known as the Sangam poems that form the most important sources for a more detailed history of the Chera family.[18][19] The Sangam poems are rich in descriptions about a number of Chera "kings" and "princes", along with the poets who extolled them. Among them, the most important sources for the Cheras are the Patitrupattu, the Akananuru, the Purananuru and perhaps the Cilapatikaram of Ilamko Atikal.[17] The Patitrupattu, the fourth book in the Ettutokai anthology of poems, mentions a number of rulers and heirs-apparent of the Chera family. Each ruler is praised in ten songs sung by the court poet.[20] However, these are not worked into connected history and settled chronology so far.[21] A method, known as Gajabahu-Cenkuttuvan synchronism, is used by some historians to help date early Tamil Sangam literature.[22] Despite its dependency on numerous conjectures, the method is considered as the sheet anchor for the purpose of dating the events in the Sangam literature.[23][24][25]

Decline of early Cheras

The Chera empire enters a period of "historical darkness" in the 6th, 7th and 8th centuries. Little is known for certain about the Cheras during this period. Kerala seems to have been affected by the Kalabhra upheaval in the 5th and 6th centuries CE. Though there is no authentic information about them, some Buddhist records mention that the Kalabhra ruler Achuta Vikkanta managed to extend his influence over a large part of Southern India. Tradition tells that he kept the Chera, Chola and Pandya rulers in his confinement. The Kalabhras were defeated around the 6th century by the rise of the Chalukyas, Pallavas and Pandyas.[5]

The main sources of knowledge of the period are through the inscriptions of other South Indian kingdoms such as the Chalukyas, Pallavas, Pandyas and the Rashtrakutas. They all claim to have overrun Kerala or at least parts of it. The Chalukyas of Badami must have conducted temporary conquests of parts of North Kerala. An inscription of Pulakeshin I claims that he conquered the Chera ruler. A number of other inscriptions mentions their victories over the kings of Chera kingdom and Ezhil Malai rulers. Pulakeshin II (610–642) is also said to have conquered Chera, Pandya and Chola kingdoms. Soon the three rulers made an alliance and marched against the Chalukyas. But the Chalukyas defeated the confederation. Vinayaditya also claims to have subjugated the Chera king and made him pay tribute to the Chalukyas. King Vikramaditya II (734-745) also claims to have defeated the Cheras. An inscription to this effect was found in Adur (Kasargod district of Kerala), perhaps testifying to their dominance in the region. Their influence came to an end in 755 CE with the rise of the Rashtrakutas.[26]

Around the same period, the Pallavas also claim conquest over the Chera kingdoms. King Simhavishnu (560-580) and Mahendra Varman (580–630) are the first Pallava rulers to claim victories over the Chera kingdom. Narasimhavarman (630–668) also claims victories over the Cheras and the Pandya ruler Sendan (654–670). King Nandivarman II of the Pallavas allied with the Cheras in a fight against the Pandya king Varaguna I. Among the other dynasties, Sendan also claims a victory over Kerala. The Rashtrakutas also claimed control over Cheras. Dantidurga (752–756) and Govinda III (792–814) are said to have had victories over the Kerala kings. In this manner, the post-Sangam era was in many ways a 'dark period' in Kerala history where it was invaded by outside powers in rapid succession. However, the claims of most of these dynasties to have established sway over Kerala at this time is not supported by any tangible evidence with the exception of the Pandyas.[27]

The Pandyan kingdom established control over Chera territories by repeated attacks on the Ays who were located on the southern border of the Cheras. The Ay kingdom, long functioned as an effective buffer state between the Chera and Pandya kingdoms. But with the decline of the Ays, the Chera kingdoms were exposed to direct conflict with the Pandyas, and later with the Cholas.[28] The Pandyas conquered the Ays and a made it a tributary state. As late as 788 CE, the Pandyas under Maranjadayan or Jatilavarman Parantaka invaded the Ay kingdom and captured the port city of Vizhinjam. However, the Ays did not seem to have submitted to the Pandyas easily, as the Ay king Karunandan, appears to have been still fighting after a decade.[29] This seems to offer proof that conquered lands in South India, such as Vizhinjam in this case, were not settled permanently but used to assert their independence at the first available opportunity.[30] Shortly thereafter, the Ay kingdom appears to have merged with Venad kingdom and there are almost no mentions of them.[31]

Later Cheras

After a period of relative obscurity between the 6th to 8th centuries CE, Chera power was revived under Kulasekhara Varman who ruled from 800 to 820 CE. The illustrious line of kings who followed were called the Kulasekharas and are also known as the Second Cheras. They ruled large parts of Kerala between 800 and 1102 CE. They ruled from their capital Mahodayapuram (also called Makotai or Mahodayapattanam), near the present day Kodungalloor, Kerala.[33] The Kulasekhara kings were also known as Perumals (Kulasekhara Perumals or Cheraman Perumals).[34]

- Conflicts and Aftermath

The second part of the Kulasekhara empire in the 10th and 11th centuries was characterised by a series of great conflicts with the Cholas in what became known as the "Hundred Years War". It is believed that Raja Raja Chola (985–1016 CE) wanted to recapture some territory which had asserted independence with the rest of Tamizhakam.[35] In c. 989, he mounted a probing attack which reached Kandalur Salai before returning. In 999, he was able to inflict a major defeat on the Cheras, defeating Chera strongholds in Kandalur and Vizhinjam. By the end of his reign, much of South Travancore came under Chola control. The wars continued into the reign of Rajendra Chola (1012–1044 CE) who also won battles at Kandalur and Vizhinjam in 1019 which had been taken back by the Cheras in the interim. The capital of the Kulasekharas, Mahodayapuram was sacked in a decisive battle when the Chola armies attacked via the Palakkad gap and this battle led to the deaths of several important chieftains and generals.[36] However, the Cheras once again regrouped and by 1070 CE, Chera territories were back under their control. Kulottunga Chola I (1070–1122) CE had to fight once again to gain Kandalur and Vizhinjam and is known to have proceeded further north and destroyed Kollam in 1096 CE. This defeat led to a major reorganisation and mobilisation of the Chera forces under the rule of Rama Varma Kulasekhara who rallied them under his banner with the primary objective of throwing out the Chola imperialists. A large body of fighters called the Chavers was raised who were styled as suicide squads. In c. 1100, the Chavers played a decisive part in the defeat of Kulottunga Chola I, inflicting heavy casualties on the Cholas and forcing them to retreat to Kottar. The Cholas were never able to conquer the Chera regions again and withdrew from the region.[37]

After the sack of Mahodayapuram and Kollam, the Chera king Rama Varma Kulasekhara moved a majority of the Chera forces further south to Kollam in order to ensure the continued protection of the southern regions of Kerala. A new capital was set up at Kollam and was called Ten Vanchi (literally the new Vanchi). The Cheras under Rama Varma Kulasekhara then seems to have merged with the existing house of Venad and this forms the next phase of the dynasty, in the form of the Venad empire. The subsequent kings of Venad take the title of "Kulasekhara" or "Kulasekhara Perumal" that used to be assumed by the Chera kings of Mahodayapuram.[38]

The prolonged series of wars with the Cholas had led to a significant weakening of the Chera ruler's control over various parts of Kerala. Some of the naduvazhis (local cheftians) tried to take advantage and assert their independence. The movement of the capital of the later Cheras further south to Kollam meant that the northern houses asserted their independence. Northern kingdoms such as Polanad (Kozhikode area), Kolathunad (North Malabar region) formed semi-independent kingdoms from their existing royal houses. Kochi, comprising the area of the old Chera capital of Mahodayapuram, formed its own Swaroopam (state) later in the 14th century CE.[39]

Government

| Chera dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Cheras | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Later Cheras | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Monarchy was considered the most important political institution of the Chera kingdom, though the extent of state formation is disputed.[4] There was a high degree of pomp and pageantry associated with the person of the king. The king wore a gold crown studded with precious stones. The king was an autocrat, but his powers were limited by the counsel of ministers and scholars. The king held daily durbar to hear the problems of the common men and to redress them on the spot. The royal queen had a very important and privileged status and she took her seat by the side of the king in all religious ceremonies.[40]

Another important institution was the manram which functioned in each village of the Chera kingdom. Its meetings were usually held by the village elders under a banyan tree, and helped in the local settlement disputes. The manrams were the venues for the village festivals as well.[41] In the course of the imperial expansion of the Cheras, the members of the royal family set up residence at several places of the kingdom. They followed the collateral system of succession according to which the eldest member of the family, wherever he lived, ascended the throne. Junior princes and heir-apparents (crown princes) helped the ruling king in the administration.[42]

Revenue was accrued through a combination of taxes on land and trade. It is unclear as to the share of the agricultural produce that was accrued by the state. Taxes were imposed on internal trade as well articles for exports and imports and this brought in a lot of revenue. Smuggling was heavily cracked down upon and elaborate arrangements were made for security in the kingdom. Roads were patrolled at night by watchmen with torches. The Cheras had a well-equipped army which consisted of infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. They were also in possession of an impressive navy fleet which was regarded as one of the most powerful in the Sangam era.[40] The Chera soldiers made offering to the war goddess Kottavai before any military operation. It was traditional when the Chera rulers were victorious in a battle to wear anklets made out of the crowns of the defeated rulers.[43]

Rulers

- Chera rulers according to the Sangam poems

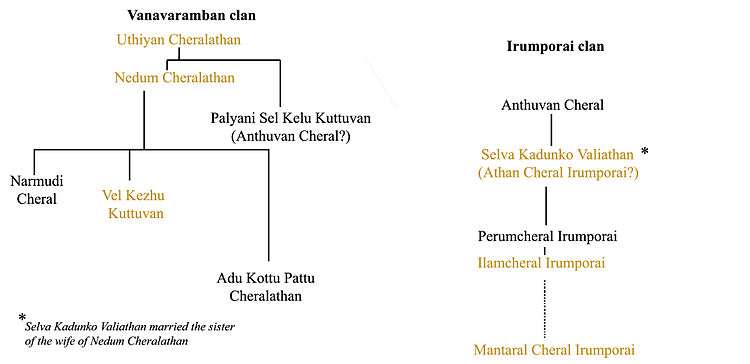

Utiyan Cheralathan - The first of the known rulers of the Chera entity, he was also known as "Vanavaramban" Perumchettutiyan Cheralathan. His capital was at Kuzhumur in Kuttanad. Uthiyan Cheralathan was a contemporary of the Chola ruler Karikala Chola. Mamulanar credits him with having conducted a feast in honour of his ancestors. In a battle at Venni, Uthiyan Cheralathan was wounded on the back by Karikala Chola. Unable to bear the disgrace, the Chera committed suicide by starvation.[44]

Nedum Cheralathan - Nedum Cheralathan is the hero of the second decad of Pathirruppaththu which was composed by the poet, Kannanar. In it, he is praised for having subdued seven crowned kings to achieve the title of Adhiraja. With characteristic exaggeration, Kannanar also lauds the king for conquering foes from Kumari to the Himalayas. Cheralathan, famous for his hospitality, gifted Kannanar with a part of Umbarkkattu (Anamalai). The greatest of his enemies were the Kadambas of Banavasi whom he defeated. The contemporaneity with the Kadambas tentatively dates Cheralathan to around the 4th century. He also won another victory over the Yavanas (westerners) on the coast. Nedum Cheralathan was killed in a battle with a Chola ruler. The Chola is also said to have been killed by a spear thrown at him by Cheralathan.[44]

Senguttuvan - Vel Kelu Kuttuvan, son of Nedum Cheralathan, ascended to the Chera throne after the death of his father. He is often identified with the legendary Kadal Pirakottiya "Senguttuvan Chera", the most illustrious ruler of the early Cheras. Under his reign, the Chera kingdom extended from Kollimalai in the east to Tondi and Mantai on the western coast. The queen of Senguttuvan was Illango Venmal (the daughter of a Velir chief).[45] In the early years of his rule, Senguttuvan successfully intervened in a civil war in the Chola Kingdom. The war was among the Chola princes and the Cheras stood on the side of their relative Killi. The rivals of Prince Killi were defeated in a battle at Neriyavil, Uraiyur and he firmly established the Chola throne. The land and naval expedition against the Kadambas was also successful. The Kadambas had the support of the Yavanas, who were routed in the Battle of Idumbil and Valyur. The Fort Kodukur in which the Kadamba army took shelter was stormed and the Kadambas was beaten. In the following naval expedition the Yavana-supported Kadamba army was crushed. He is said to have defeated the Kongu people and a warrior called Mogur Mannan. Ilango Adigal wrote the legendary Tamil epic Silappatikaram, which describes his brother Senguttuvan Chera's decision to propitiate a temple (Virakkallu) for the goddess Pattini (Kannagi) at Vanchi.

Senguttuvan Chera was perhaps a contemporary of Gajabahu, king of Sri Lanka. Gajabahu, according to the Sangam poems, visited the Chera country during the Pattini festival at Vanchi.[46] He is mentioned in the context of Gajabahu’s rule in Sri Lanka, which can be dated to either the first or last quarter of the 2nd century CE, depending on whether he was the earlier or the later Gajabahu.[6]

Selvakadumko Valiathan - Selvakadumko Valiathan was the son of Anthuvan Cheral and the hero of the 7th set of poems composed by Kapilar. His residence was at the city of Tondi. He married the sister of the wife of Nedum Cheralathan. Selva Kadumko defeated the combined armies of the Pandyas and the Cholas. He is sometimes identified as the Athan Cheral Irumporai mentioned in the Aranattar-malai inscription of Pugalur.[47]

Perum Cheral Irumporai - "Tagadur Erinta" Perum Cheral Irumporai defeated the combined armies of the Pandyas, Cholas and that of the chief of Tagadur(now called as Dharmapuri). He destroyed the famous city of Tagadur which was ruled by the powerful ruler Adigaman Ezhni. He is also called "the lord of Puzhinad and Kollimala" and "the lord of Puhar". Puhar was the Chola capital. Perum Cheral Irumporai also annexed the territories of a minor chief called Kaluval.[48]

Illam Cheral Irumporai - Illam Cheral Irumporai defeated the Pandyas and the Cholas and brought immense wealth to his capital at a city called Vanchi. He is said to have distributed these treasures among the Pana poets.[48]

Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai - King Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai preserved the territorial integrity of the Chera Kingdom under his rule. However, by the time of Mantaran Cheral the decline of the kingdom had begun. The Chera ruled from Kollimalai in the east to Tondi and Mantai on the western coast. He defeated his enemies in a battle at Vilamkil. The famous Pandya ruler Nedum Chezhian captured Mantaran Cheral as a prisoner. However, he managed to escape and regain the lost kingdom.[49]

Kanaikkal Irumporai - Kanaikkal Irumporai is said to have defeated a local chief called Muvan. The Chera then brutally pulled out the teeth of his prisoner and planted them on the gates of the city of Tondi. Kanaikkal Irumporai was later captured by the Chola ruler Sengannan and he committed suicide by starvation.[49]

- Archaeological sources

Archaeology has found epigraphic evidence of the early Cheras.[50] Two identical inscriptions near Tiruchirappalli, dated to the 2nd century CE, describe three generations of Chera rulers of the Irumporai clan. They record the construction of a rock shelter for Jains on the occasion of the investiture of the crown prince Ilam Kadungo, son of Perum Kadungo, and the grandson of Athan Cheral Irumporai.

- Later Chera or Kulasekhara rulers

| Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai[51] | M. G. S. Narayanan[52] |

|---|---|

|

|

Administration

Mahodayapuram, Mahodayapattanam or Makotai was the capital city of Chera dynasty between 8th and 12th centuries CE. It was spread around present-day Kodungallur.[53]

The city was built around Tiruvanchikkulam temple and was protected by high fortresses on all sides and had extensive pathways and palaces. The temple was a centre of Shaivism in the early years of the later Chera age. The royal palace was at Gotramalleswaram, now known as Cheraman Parambu. The city administration was controlled by a special representative body, the Kuttam. Mahodayaouram was also called Vanchi by the later Chera rulers after their former capital.[45]

The Chera rulers shifted their capital to Mahodayapuram from Vanchi. Chera ruler Kulashekhara Varman (9th century) styles himself in his works as the "Lord of Mahodayapuram". The famous Jewish Copper Plate grant (1000 CE) was issued by Muyirikkode (Mahodayapuram).[45]

Mahodayapuram was famous throughout South India in the 9th and 10th centuries as great centre of learning and science. A well-equipped observatory functioned there under the charge of Sankaranarayana (c. 840 – c. 900), the Chera court astronomer.[54] It functioned in accordance with the rules of astronomy laid down by Aryabhata. The Chera ruler, Sthanu Ravi, equipped a section of the observatory with some special yantras (Rasi Chakra, Jalesa Sutra, Golayantra etc.) and hence it came to be called Ravi Varma Yantra Valayam. It seems that arrangements had been made in the city for recording correct time and announcing it to the public from different centres by the tolling of bells at regular intervals of a Ghatika (25 minutes). This practice (Nazhikakkottu) continued until the early 15th century.[55]

The localities within the city included:[53]

- Senamugham

- Kottakkakam

- Gotramalleswaram

- Kodungallur

- Balakrideswaram

Economy

Foreign trade

Chera trade with foreign countries around the Mediterranean sea can be traced back to before the Common Era and was substantially consolidated in the early years of the Common Era.[56][57] In the 1st century of the Common Era, the Romans conquered Egypt, which helped them to establish dominance in the Arabian sea trade. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea portrays the trade in the kingdom of Cerobothras in detail. Muziris was the most important port in the Malabar coast, which according to the Periplus, abounded with large ships of Romans, Arabs and Greeks. Bulk spices, ivory, timber, pearls and gems were exported from the Chera ports to Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Phoenicia and Arabia.[58] The Romans brought vast amounts of gold in exchange for pepper.[59][60][61] This is testified by the large number of Roman coins that have been found in various parts of Kerala. Pliny, in the 1st century CE, laments about the drain of Roman gold into India and China for unproductive luxuries such as spices, silk and muslin. This trade declined with the decline of the Roman empire in the 3rd-4th centuries CE.

There were also extensive trade contacts with the Chinese and this is confirmed by the discovery of Chinese coins from the 1st century CE. It is speculated by some authors that the trade with China is older and lasted longer than the trade with the Greeks and the Phoenicians. Kollam was an important port of trade with the Chinese and Marco Polo, in the 15th century CE, discovers extensive trade ties between Kerala and China, mainly in the trade of pepper.

Society and culture

Early Cheras

Most of the Chera population followed native Dravidian practices. The worship of departed heroes was a common practice in the Chera kingdom along with tree worship and other kinds of ancestor worship. The war goddess Kottavai was propitiated with elaborate offerings of meat and toddy. The Cheras probably worshipped this mother goddess. It is theorised that Kottavai was assimilated into the present-day form of the goddess Durga. There is no evidence of snake worship in the Chera realms during the Sangam Age.[62] It is thought that the first wave of Brahmin migration came to the Chera kingdom around the 3rd century BCE behind the Jain and Buddhist missionaries. It was only in the 8th century CE that the Aryanisation of the Chera country reached its climax.[63]

Though the vast majority of the population followed native Dravidian practices, a small percentage of the population followed Jainism, Buddhism and Brahmanism. These three philosophies came from regions in northern India to the Chera kingdom.[62] Populations of Jews and Christians were also known to have lived in these territories.[64][65][66]

The division of the society into castes and communities was conspicuously absent and practices of untouchability and exclusiveness were unknown. There was dignity of labour accorded to all work and no one was looked down upon due to their work or occupation.[41] A striking feature of the social life of the Cheras in the Sangam age is the high status accorded to women. Women enjoyed freedom of movement as well as the right to full education. Child marriage was unknown in the early Sangam era and adult marriage was the general rule. The practice of 'bride-price', where the groom would pay the girl's parents, appears to be prevalent in the time. Women were free to follow any occupation though most of them were involved in weaving or the sale of goods.[67] A martial spirit was pervasive and women even went to the battlefield along with the men, largely playing a key role in keeping up the morale of the fighting forces.

Agriculture was the primary occupation of the people and rice was the main staple of the people. Various agricultural occupations such as harvesting, threshing and drying are described. Fish and meat were also eaten liberally. There is a mention of ney-ven choru or butter-laden rice with meat of the best quality being served to guests assembled for a wedding (mentioned in Agam 136). Liquor, mainly wines, that were brought by the Yavanas (or Westerners) was quite popular. However, the local population was partial to palm-wine or Toddy. Music, poetry and dancing provided entertainment for the people. And poets and musicians were held in high regard in society. Sangam literature is full of references about the lavish patronage extended to court poets. There were professional poets and poetesses who composed poems praising their patrons and were generously rewarded for this. Musical instruments such as drums, pipes and flutes were also known in the time.[68]

Later Cheras

The early period of the Kulasekharas i.e. the period of the 9th and 10th centuries constitutes a "golden period" in the history of Kerala. There was great patronage of the arts, literature and science and several important contributions in these fields were made during this period. At its height, the Kulasekhara empire comprised almost all of modern-day Kerala, some parts of the Nilgiri hills and parts of the Salem-Coimbatore regions. Political administration was distributed federally and the various areas were divided into various administrative provinces called nadus. The southern-most region was the Venad, comprising regions of modern-day Thiruvananthapuram and Kollam, while the northern-most was called the Kolathunadu and comprised areas of Kannur and Kasaragod. The administration of these nadus was carried out by feudatory local chieftains also known as naduvazhis. These chieftains were overseen by royal representatives named koyiladhikarikal who were usually selected from the blood relations of the Kulasekhara's family.Each of these nadus or provinces were sub-divided into smaller Desams. These desams were governed by desavazhis who were usually selected by the local representative bodies named kuttams.[69]

The Chera state had extensive trade relations with countries of the outside world. The most important ports of this period were Kandalur (near Vizhinjam), Kollam and Kodungallur. Sulaiman and al-Mas'udi, the Arab travellers who visited the Malabar Coast during the period, have testified to the high degree of economic prosperity achieved by the state from its foreign trade. Sulaiman makes specific mention of the brisk trade with China. A number of copper-plates and inscriptions testify to the high importance given to trade corporations and merchant guilds.[70]

The Kulasekhara period is characterised by a great flowering of the arts and literature. Several notable works in Sanskrit and Tamil were written during this period under the patronage of the Kulasekharas who themselves indulged in authoring several works. Malayalam emerged with its own distinct script around this period, around the Kollam era (early 9th century). Hinduism as a religion, became more prominent around this period and was accompanied by a corresponding decline in Buddhism and Jainism. There was an increase in the number of Vedic schools called salais and an increase in their prestige with the widespread prominence of the Advaita philosopher, Adi Shankara, who was born at Kaladi on the banks of the river Periyar.[71] The Kulasekhara empire was characterised by eclectic beliefs and religious harmony that was free from sectarian conflict evidenced by the simultaneous existence of several religions. This is also evidenced in the form of grants given to Christians as well as copper-plate grants given to the Jews of Kochi.[72]

Copper-plate grants

The Vazhapally Plates are a set of copper-plate grants issued by Kulasekhara Mahodayapuram king, Rajashekhara Varman (820–844).[73]

The Tharisapalli plates are a set of copper-plate grants issued to Mar Sapir Iso, the leader of the Saint Thomas Christians by Ayyan Atikal Thiruvatikal in 849, conferring on the Palli and Palliyar a large number of privileges, including the 72 royal rights. These copper-plates are still present at Devalokam Aramana Kottayam, the headquarters of Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (successor to the Saint Thomas Christians).[73][74][75]

The Jewish copper plate was given to the Cochin Jews by the Kulasekhara king, Bhaskara Ravi Varman I (962–1019 CE). This inscription conferred on a Jewish leader, Joseph Rabban, the rights of the Anjuvannam and 72 other proprietary rights.[76][77]

Cheras of Venadu

In the absence of a central power at Makkotai, the divisions of the Chera kingdom soon emerged as principalities under separate chieftains. The post-Chera period witnessed a gradual decadence of the Nambudiri-Brahmans and rise of the Nairs.

The original Chera dynasty migrated to Kollam (Quilon) and merged with the Ay kingdom. Ramavarma Kulasekhara, the last Chera King of Makotaiya Puram (Kodungaloor), became the first ruler of the Chera-Ai Dynasty and was called Ramar Thiruvadi.

The rulers of the kingdom of Venadu, based at port Quilon in southern Kerala, trace their relations to the Perumals of Makkotai. Venadu ruler Kotha Varma (1102–1125) probably conquered Kottar and portions of Nanjanadu from the Pandyas. Under the reign of Vira Ravi Varma the system of government became very efficient, and village assemblies functioned vigorously. Udaya Marthanda Varma's tenure was noted for the close relationship between the Venadu and Pandyas. By the time of Ravi Kerala Varma (1215–1240), Odanadu kingdom had acknowledged the authority of the Venadu rulers. The next Venadu ruler Padmanabha Marthanda Varma is alleged to have been killed by Vikrama Pandya in 1264 CE.[45]

The Pandyas probably led a successful military expedition to Venadu and captured the capital city of Quilon between 1250 and 1300 CE. The records of Jatavarman Sundara Pandya and Maravarman Kulasekhara Pandya testify to the establishment of Pandya rule over Venadu Cheras.[78]

- Ravi Varma Kulasekhara

Ravi Varma Kulasekhara, the last of the Venadu kings, ruled Venadu as a vassal of the Pandyas till the death of king Maravarman Kulasekhara. After the death of the king he became independent and even claimed the throne of the Pandyas (Ravi Varma had married the daughter of the deceased Pandya ruler). He later annexed large parts of southern India and raised Venadu Cheras to the position of a powerful military state for a short time. The chaotic succession battles in the Pandya kingdom helped his conquests. The Venadu ruler invaded the Pandya kingdom and defeated the forces of Vira Pandya. After annexing the entire Pandya state, he was crowned as "Emperor of South India" in 1312 at Madurai. He later annexed Tiruvati and Kanchi (the Chola kingdom). Under Ravi Varma Venadu attained a high degree of economic prosperity.[79]

The success of Ravi Varma was short lived and soon after his death the region became a conglomeration of warring states. Venadu itself transformed into one these states. The line of Venadu kings after Ravi Varma continued through the law of matrilineal succession.

Aditya Varma Sarvanganatha (1376–1383) is known have defeated the Muslim raiders of the south and checked the tide of Islamic advance. Under the rule of Chera Udaya Marthanda Varma, the Venadu gradually extended their sway over the Tirunelveli region. Vira Ravi Ravi Varma (1484–1503) was the ruler of Venad during the arrival of the Portuguese in India.[45]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Citing Komattil Achutha Menon, Ancient Kerala, p. 7[11]

- ↑ According to Menon, this etymology of "added" or "reclaimed" land also complements the Parashurama myth about the formation of Kerala. In it, Parashurama, one of the avatars of Vishnu, flung his axe across the sea from Gokarnam towards Kanyakumari (or vice versa) and the water receded up to the spot where it landed, thus creating Kerala.[12]

References

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ "Cera dynasty". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ↑ Karashima 2014, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 Narayanan, M. G. S. (2013). Perumāḷs of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy : Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cēra Perumāḷs of Makōtai (c. AD 800 - AD 1124). ISBN 9788188765072.

- 1 2 3 Menon 2007, p. 81.

- 1 2 "India – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ↑ Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Ed. by Edward Balfour (1871), Second Edition. Volume 2. p. 584.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 73.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 118.

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 368.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 21.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 20,21.

- ↑ Keay, John (2000) [2001]. India: A history. India: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ↑ Caldwell 1998, p. 92.

- ↑ M. Ramachandran, Irāman̲ Mativāṇan̲(1991). The spring of the Indus civilisation. Prasanna Pathippagam, pp. 34. "Srilanka was known as "Cerantivu' (island of the Cera kings) in those days. The seal has two lines. The line above contains three signs in Indus script and the line below contains three alphabets in the ancient Tamil script known as Tamil ...

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 33.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, p.12

- ↑ K.A. Nilakanta Sastry, A History of South India, OUP (1955) p.105

- ↑ Subodh Kapoor (1 July 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 1449. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ Barbara A. West (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 781. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ V., Kanakasabhai (1997). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0150-5.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 37–39: The opinion that the Gajabahu Synchronism is an expression of genuine historical tradition is accepted by most scholars today

- ↑ Pillai, Vaiyapuri (1956). History of Tamil Language and Literature; Beginning to 1000 AD. Madras, India: New Century Book House. p. 22.

We may be reasonably certain that chronological conclusion reached above is historically sound

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, p. 38.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 82.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 99.

- ↑ K.A. Nilakanta Sastri (1976) - The Pandyan kingdom, pg 76

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 102.

- ↑ Karashima 2014, p. 132.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 111.

- ↑ Focus on a PhD thesis that threw new light on Perumals - R. Madhavan Nair [The Hindu], 2 April 2011

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 115.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 118,140–141.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 138,147.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 75.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 77.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 75–76.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, pp. 67–68.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Menon 1967.

- ↑ See Mahavamsa – http://lakdiva.org/mahavamsa/. Since Senguttuvan (Kadal Pirakottiya Vel Kezhu Kuttuvan) was a contemporary of Gajabahu I of Sri Lanka he was perhaps the Chera king during the 2nd century CE.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 70.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 71.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 72.

- ↑ See report in Frontline, June/July 2003

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 111–119.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 122.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 126.

- ↑ George Gheverghese Joseph (2009). A Passage to Infinity. New Delhi: SAGE Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-321-0168-0.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 126,127.

- ↑ "Artefacts from the lost Port of Muziris." The Hindu. December 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Pattanam richest Indo-Roman site on Indian Ocean rim." The Hindu. May 3, 2009.

- ↑ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 105–.

- ↑ http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/thscrip/print.pl?file=2007012800201800.htm&date=2007/01/28/&prd=th&

- ↑ "History of Ancient Kerala". Government of india. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Raoul McLaughlin, Rome and the distant East: trade routes to the ancient lands of Arabia, India and China Continuum International Publishing Group, 6 July 2010

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 83.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 89.

- ↑ The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 5 by Erwin Fahlbusch. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing – 2008. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2.

- ↑ Manimekalai, by Merchant Prince Shattan, Gatha 27

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 78.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 127.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 128,129.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 135.

- 1 2 Menon 2007, p. 112.

- ↑ M. G. S. Narayanan (1972), Cultural Symbiosis, Kerala Society.

- ↑ George Menachery (1998) Indian Church History Classics, Vol. I, The Nazranies, SARAS.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 114.

- ↑ Fischel 1967, pp. 230.

- ↑ Menon 2007, p. 142.

- ↑ Menon 2007, pp. 143–144.

Sources

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (2007). A survey of Kerala history (2007 ed.). Kerala, India: D C Books. ISBN 8126415789.

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (1967). A Survey of Kerala History. Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society. OCLC 555508146.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (Fourth ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780415329200.

- Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India : from the origins to AD 1300. Berkeley [u.a.]: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520242258.

- Karashima, Noboru (2014). A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198099772.

- Kamil Zvelebil (1975). Tamil Literature. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-04190-5.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The smile of Murugan: On Tamil literature of south India. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

- Robert Caldwell (1998) [1913]. A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages (3rd ed.). Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0117-8.

- Fischel, Walter J. (1967). "The Exploration of the Jewish Antiquities of Cochin on the Malabar Coast". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 87 (3): 230–248. doi:10.2307/597717. JSTOR 597717.

- Narayanan, M.G.S. (2013). Perumāḷs of Kerala : Brahmin oligarchy and ritual monarchy : political and social conditions of Kerala under the Cēra Perumāḷs of Makōtai (c. AD 800-AD 1124). Thrissur: CosmoBooks. ISBN 9788188765072.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chera Dynasty. |