History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

|

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Colonial

|

|

Post-Independence

|

| History of Pakistan |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Pakistan |

|

| Timeline |

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Early modern

|

|

Modern

|

|

History of provinces |

|

The History of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa concerns the history of the North Western region of what is now the state of Pakistan, as well as the surrounding areas that have been colloquially referred to as Pashtunistan. The earliest evidence from the region indicates that trade was common via the Khyber Pass; originating from the Indus Valley Civilization. The early people of the region were a Vedic people known as the Pakthas, identified with the modern day Pakhtun peoples. The Vedic culture reached its peak between the 6th and 1st centuries B.C under the Gandharan Civilization, and was identified as a center of Hindu learning and scholarship.

The area saw a brief shock during the invasions of Alexander the Great, which had managed to conquer the small Janapadas——or city states——that had ruled the region. Seizing the resulting instability and inexperience of the local Greek governors, a young prince named Chandragupta Maurya managed to take control of the area, eventually going on to conquer much of Northern India. Over time the Mauryan Empire, from Chandragupta's line, had went on to conquer much of the Indian Subcontinent with the Empire reaching its peak under King Ashoka. Ashoka had converted to Buddhism from Hinduism, and with his conversion, declared that the official state religion of the Empire was the former. Ashoka's rule had witnessed a rise in Buddhism throughout India, although Hinduism was not displaced. After Ashoka's death, the Mauryan Empire had crumbled under the weak rule of the later Kings.

With the disintegration of the centralized Mauryan Empire, the North West frontier was once again ruled by small Kings and Chieftans. Brief invasions from nomadic tribes to the north of the Khyber pass had also resulted in new displacements across the region, but nevertheless, had resulted in the maintenance of Hindu rule. Over time the Shahis,who had often alternated between Hinduism and Buddhism, had managed to gain control of the region and ruled starting from around the first century A.D. The Shahis were initially based in what is now Afghanistan, but Turkic invasions had forced a relocation further south into Peshawar. The Shahis were finally destroyed after the defeat of King Jayapala in A.D 1001 by the Ghaznavids led by Mahmud of Ghazni. After the Ghaznavids, various other Islamic rulers had managed to invade the region, with the most notable being the Delhi Sultanates who had with respect to various dyansties ruled starting from A.D 1206. The rule of the Delhi sultanates was characterized by near constant wars, with a notable example being the repulsion of a Mongol force led by Genghis Khan. Nevertheless, after the battle of Panipat in A.D 1526, the Mughals had taken control of the region, and managed to rule until the early 18th century when they were displaced by the brief rule of the Sikhs.

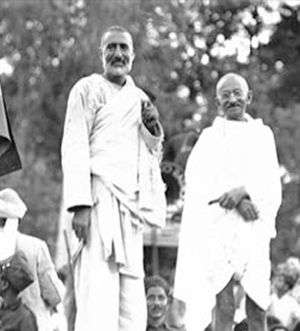

Seizing the lack of a centralized authority in India, the British Empire had managed to take control of the region around 1857, and had ruled until the Indo-Pakistani Independence of 1947. British rule was characterized by constant tensions between the local people and the Government, resulting in some violent altercations between both groups. Nevertheless, there was peaceful challenges to the British authority, such as that of Pashtun leader Abdul Ghaffar Khan and his Khudai Khidmatgar. After Independence the area was renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after widespread petitioning to the Pakistan government by the local Pashtuns. Today, the area is a key province in the war on terror; and aside from terrorism, the province continues to face many developmental challenges.

Vedic Era

During the times of Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE - 1700 BCE) the Khyber Pass through Hindu Kush provided a route to other neighbouring empires and was used by merchants on trade excursions.[1]

The Vedic Gandharan civilization, which was at its peak between the sixth and first centuries BCE, and which features prominently in the Hindu epic poem, the Mahabharatha,[2] was primarily based in the area in and between modern day Afghanistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The city of Peshawar was originally called Purushapura in ancient times when the region was Hindu. Vedic texts refer to the area as the Janapada of Pushkalavati. The area was once known to be a great center of learning.[3]

The people of the region were a Vedic people known as the Pakthas, identified with the modern Pakthun people. This name was also confirmed by Ancient Greek sources, such as those from the works of Herodotus.[4][5][6] The Pakthas are notably mentioned in Mandala VII of the Rigveda as one of the tribes that had fought with Raja Sudas at the Battle of the Ten Kings.[7]

Mauryan Era

Alexander's conquests

In the spring of 327 BC Alexander the Great crossed the Indian Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and advanced to Nicaea, where Omphis, king of Taxila and other chiefs joined him. Alexander then dispatched part of his force through the valley of the Kabul River, while he himself advanced into Bajaur and Swat with his light troops.[2] Craterus was ordered to fortify and repopulate Arigaion, probably in Bajaur, which its inhabitants had burnt and deserted. Having defeated the Aspasians, from whom he took 40,000 prisoners and 230,000 oxen, Alexander crossed the Gouraios (Panjkora) and entered the territory of the Assakenoi and laid siege to Massaga, which he took by storm. Ora and Bazira (possibly Bazar) soon fell. The people of Bazira fled to the rock Aornos, but Alexander made Embolima (possibly Amb) his base, and attacked the rock from there, which was captured after a desperate resistance. Meanwhile, Peukelaotis (in Hashtnagar, 17 miles (27 km) north-west of Peshawar) had submitted, and Nicanor, a Macedonian, was appointed satrap of the country west of the Indus.[8]

Mauryan rule

After the Macedonians had left, Chandragupta Maurya displaced the Nanda Empire and established the Mauryan Empire. A while after, Alexander's general Seleucus had attempted to once again invade the subcontinent from the Khyber pass hoping to take lands that Alexander had conquered,but never fully absorbed into this empire. Seleucus was defeated and the lands of Aria, Arachosia, Gandhara, and Gedrosia were ceded to the Mauryans in exchange for a matrimonial alliance and 500 elephants. With the defeat of the Greeks, the land was once more under Hindu rule.[9] Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka converted to Buddhism and made it the official state religion in Gandhara and also Pakhli, the modern Hazara, as evidenced by rock-inscriptions at Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra.[8]

After Ashoka's death the Mauryan empire fell to pieces, just as in the west the Seleucid power was waning. The Greek princes of Bactria seized the opportunity for declaring their independence, and Demetrius conquered part of Northern India (c. 190 BC). His absence led to a revolt by Eucratides, who seized on Bactria proper and finally defeated Demetrius in his eastern possessions. Eucratides was, however, murdered (c. 156 BC), and the country became subject to a number of local rulers, of whom little is known but the names laboriously gathered from their coins. The area was attacked from the west by the Parthians and the north by the Sakas, a Central Asian tribe around 139 B.C. Local Greek rulers still exercised a feeble and precarious power along the borderland, but the last vestige of the Greco-Indian rulers were finished by a people known to the old Chinese as the Yeuh-Chi.[8]

Kushan rule

This race of nomads had driven the Sakas from the highlands of Central Asia, and were themselves forced southwards by the nomadic Xiongnu. One group, known as the Kushan, took the lead, and its chief, Kadphises I, seized vast territories extending south to the Kabul valley. His son Kadphises II conquered North-Western India, which he governed through his generals. His immediate successors were the fabled Hindu kings: Kanishka, Huvishka, and Vasushka or Vasudeva, of[8] whom the first reigned over a territory which extended as far east as Benares, far south as Malwa, and also including Bactria and the Kabul valley.[10] Their dates are still a matter of dispute, but it is beyond question that they reigned early in the Christian era. To this period may be ascribed the fine statues and bas-reliefs found in Gandhara and Udyana. Under Huvishka's successor, Vasushka, the dominions of the Kushan kings shrank to the Indus valley and the modern Afghanistan.[10]

Shahi rule

Between the 0 A.D and the 1st millennium, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region was ruled by Hindu-Buddhist Shahi kings. When the Chinese monk Xuanzang visited the region early in the 7th century, the Kabul valley region was still ruled by affiliates of the Shahi kings, who is identified as the Shahi Khingal, and whose name has been found in an inscription found in Gardez. During the rule of the Shahis, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region was a center of trade. Textiles, gems, and perfumes, as well as other goods had been exported West and into Central Asia. Coins minted by the Shahis have been found all over South Asia. The Shahis were known for their many Hindu temples. These temples were mostly looted and destroyed by later invaders. The ruins of these temples can be found at Nandana, Malot, Siv Ganga, and Ketas, as well as across the west bank of the Indus river.[12][13]

Arrival of Islam

Ghaznavids

At the height of Shahi rule under King Jayapala, the kingdom had extended to Kabul and Bajaur to the Northwest, Multan to the South, and the India-Pakistan border to the East.[12] Jayapala, threatened from the consolidation of power by the kingdom of Ghazna, invaded their capital city of Ghazni . This had initiated the Muslim Ghaznavid and Hindu Shahi struggles.[14] In 974 Pirin, the slave-governor of Ghazni, repulsed a force sent from India to seize that stronghold, then in 977 Sabuktagin, his successor, became virtually independent and founded the dynasty of the Ghaznavids. In 986 he raided the Indian frontier, and in 988 defeated Jaipal with his allies at Laghman. Soon afterwards he took control of the country as far as the Indus, placing a governor of his own at Peshawar. Mahmud of Ghazni, Sabuktagin's son, having secured the throne of Ghazni, again defeated Jayapala in his first raid into India (1001), Battle of Peshawar, and in a second expedition defeated Anandpal (1006), both near Peshawar. He also (1024 and 1025) raided the Pashtuns.[10] Over time, Mahmud of Ghazni had pushed further into the subcontinent, as far as east as modern day Agra. During his campaigns, many Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries had been looted and destroyed, as well as many people being forcibly converted into Islam.[15] Local Pashtun and Dardic tribes converted to Islam, while retaining some of the pre-Islamic Hindu-Buddhist and Animist local traditions such as Pashtunwali.[16]

1100-1520

In 1179, Muhammad of Ghor took Peshawar, capturing Lahore from Khusru Malik two years later. After Muhammad's assassination in 1206, his general Taj-ud-din Yalduz established himself at Ghazni with his true stronghold in the Kurram valley until he was driven deeper into India by the Khwarizmis in 1215. The latter were in turn overwhelmed by the Mongols in 1221, when Jalal-ud-din Khwarizmi, defeated on the Indus by Genghis Khan, retreated into the Sind-Sagar Doab, leaving Peshawar and other provinces to be ravaged by the Mongols.In 1224 Jalal-ud-din appointed Saif-ud-din Hasan, the Karlugh, as ruler of Ghazni. To this territory Saif-ud-din added Karman (Kurram) and Banian (Bannu), which gained its independence in 1236.[17]

In that same year of 1236, Altamsh set out on an expedition against Banian but he was compelled by illness to return to Delhi. After the death of Atlmash, Saif-ud-din attacked Multan only to be repulsed by the feudatory of Uch. Three years later in 1239, the Mongols drove Saif-uf-Din out of Ghazni and Kurram though he held onto Banian. In his third attempt to take Multan in 1249 he was killed. His son Nasir-ud-din Muhammad became a feudatory of the Mongols, retaining Banian. Eleven years later, in 1260 Nasir-ud-din Muhammad arranged an alliance through his daughter and a son of Ghiyas-ud-din Balban, reconciling the Mongol sovereign with the court of Delhi. By this time the Karlughs had established themselves in the hills.[17]

In 1398, Timur set out from Samarkand to invade India. After subduing Kator, now Chitral, he made devastating inroads into the Punjab, returning via Bannu in March 1399. His expedition established a Mongol overlordship in the province, and he is said to have confirmed his Karlugh regent in the possession of Hazara. The descendants of Timur held the province as a dependency of Kandahar. With the decay of the Timurid dynasty, their control over the province relaxed.[17]

Meanwhile, the Pashtuns now appeared as a political factor. At the close of the fourteenth century they were firmly established in their present-day demographics south of Kohat, and in 1451 Bahlol Lodi's accession to the throne of Delhi gave them a dominant position in Northern India. Somewhat later, Babar's uncle Mirza Ulugh Beg of Kabul expelled the Khashi from his kingdom, and compelled them to move eastwards into Peshawar, Swat, and Bajaur. After Babar had seized Kabul he made his first raid into India in 1505, marching down the Khyber, through Kohat, Bannu, Isa Khel, and the Derajat, returning by the Sakhi Sarwar pass. About 1518 he invaded Bajaur and Swat, but was recalled by an attack on Badakhshan.[17]

Mughal era

In 1519, Babar's aid was invoked by the Gigianis against the Umr Khel Dilazaks. Both were Pashtun tribes, and Babar's victory at Panipat in 1526 gave him control of the province. On his death in 1530 Mirza Kamran became a feudatory of Kabul. By his aid the Ghworia Khels overthrew the Dilazaks who were loyal to Humayun, and thus obtained control over Peshawar; but about 1550 Gajju Khan, at the head of a Grand Confederation of the Khakhay Khels, defeated the Ghworia Khels at Shaikh Tapur. Humayun at this point had overthrown Kamran, and entered Peshawar; ultimately leaving a garrison there.[18]

On Humayun's death in 1556, Kabul became the apanage of Mirza Muhammad Hakim, Akbar's brother; and in 1564 he was driven back on Peshawar by the ruler of Badakhshan, and had to be reinstated by imperial troops. Driven out of Kabul again two years later, he invaded Punjab; but eventually Akbar forgave him, visited Kabul, and restored his authority. When Mirza Hakim died in 1585, Akbar's Rajput general Kunwar Man Singh occupied Peshawar and Kabul where the imperial rule was re-established. Mann Singh became governor of the province of Kabul. In 1586, however, the Mohmands and others revolted under Jalala, the Roshania heretic, and invaded Peshawar.[18]

Man Singh, turning to attack them, found the Khyber closed and was repulsed, but subsequently joined Akbar's forces. Meanwhile, the Yusufzai and Mandaur Pashtuns had also joined the Roshania rebellion; and c.1587 Zain Khan was dispatched into Swat and Bajaur to suppress them. The expedition resulted in defeat for the Mughals. The Roshanias, however, were not fully subdued. Tirah was their stronghold, and in about 1620 a large Mughal force was defeated at the Sampagha pass.[18] Six years later Ihdad, the Roshania leader, was killed ; but Jahangir's death in 1627 was the signal for a general Pashtun revolt, and the Roshanias laid siege to Peshawar in 1630, but retreated to Tirah due to distrust for their allies. Mughal authority was thus restored, and Tirah was invaded and pacified by the imperial troops in an arduous campaign. Shah Jahan's rule was unpopular with the Pashtuns, but nevertheless, Raja Jagat Singh held Kohat and Kurram, and thus kept open the communications with Kabul. In 1660 Tirah had to be pacified again; and in 1667 the Yusufzai and Mandaur Pashtuns had crossed the Indus to attack, and were defeated near Attock.[18]

In 1672 Muhammad Amin Khan, Subahdar of Kabul, attempted to cross the Khyber pass, and was defeated. Khan's whole army of 40,000 as well as supplies and other materials were destroyed. Other disasters followed. At Gandab in 1673 the Afridis defeated a second Mughal army, and in 1674 they defeated a third force at Khapash and drove it into Bajaur.[19]

Aurangzeb was described to have adopted a conciliatory policy towards the Pashtuns, some of whom now received fiefs from the emperor. This is believed to have prevented any concerted Afghan uprising against the Mughals. Nevertheless, the Pashtuns overran the Pakhli district of Hazara early in the eighteenth century and the Mughal power rapidly declined until in 1738 when Nadir Shah defeated Nazir Shah, the Mughal governor of Kabul, but allowed him as feudatory to retain that province, which included Peshawar and Ghazni.[19]

Of Nadir Shah's successors, Ahmad Shah Durrani established something more nearly approaching a settled government in the Peshawar valley than had been known for years, but with the advent of Timur Shah, anarchy returned once more. On the death of Timur Shah his throne was contested with varying fortunes by his sons, whose dissensions gave ample opportunity to the local chieftains throughout the province for establishing complete independence.[19]

Decline of Islamic Rule

Under the Pashtuns, Hazara-i-Karlugh, Gandhgarh and the Gakhar territory were governed from Attock; while Kashmir collected the revenue from the upper regions of Pakhli, Damtaur and Darband. In 1813, the Sikhs conquered the fort of Attock, at which time lower Hazara became tributary to them.In 1818 Dera Ismail Khan surrendered to a Sikh army. Five years later the Sikhs attacked the Marwat plain of Bannu. The Sikhs forayed into Peshawar for the first time in 1818, but did not occupy the territory. The Sikhs entered the city of Peshawar for a second time, once again affirming to hold Peshawar as a tributary to the Sikh Court of Lahore. After attacking the city they burnt its fortress, the Bala Hissar. In 1836 all authority was taken from the Nawabs of Dera Ismail Khan and a Sikh Kardar appointed in their place. But it was not until after the first Sikh War that the fort of Bannu was built and the Bannuchis brought under the direct control of the Lahore Darbar by Herbert Edwardes. By 1836, with the conquest of Jamrud the frontier of the Sikh Kingdom bordered the foothills of the Hindu Kush Mountains and the Khyber Pass formed its western boundary.[19] Upper Hazara shared the same fate in 1819, when the Sikhs conquered Kashmir. The territory referred to as Hazara was united when it was bestowed as a jagir to Hari Singh Nalwa, Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh army, by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1822.[20]

The death of Hari Singh in battle with the Pashtuns near Jamrud in 1837 brought home to Ranjit Singh, now nearing the close of his career, the difficulty of administering his frontier acquisitions. On his death the Sikh policy was changed. Turbulent and exposed tracts, like Hashtnagar and Miranzai, were made over in jagir to the local chieftains, who enjoyed an almost complete independence, and a vigorous administration was attempted only in the more easily controlled areas.[19]

The most significant contributions of Sikh rule to this region were the city of Haripur, the first planned city in this entire region, and the forts of Sumergarh (Bala Hissar, Peshawar) and Fatehgarh (Fort of Jamrud at the mouth of the Khyber Pass).[21]

British Raj

.jpg)

Following the treaties of Lahore and Amritsar, the British annexed the frontier territory after the proclamation of 29 March 1849. For a short time the Districts of Peshawar, Kohat, and Hazara came under the direct control of the Board of Administration at Lahore, but about 1850 they were formed into a regular Division under a Commissioner. Dera Ismail Khan and Bannu, under one Deputy-Commissioner, formed part of the Leiah Division till 1861, when two Deputy-Commissioners were appointed and both Districts were included in the Derajat Division, an arrangement maintained until the formation of the North-West Frontier Province. The province was created during the colonial rule of the British empire and was a province of British India. As a province of British India it had an area of 38,665 square miles (100,140 km2), of which only 13,193 was under direct control of the British, the remainder occupied by the tribes under the political control of the Agent to the Governor-General.[22] [18]

For one reason or another almost every tribe beyond the border was under a blockade. When the news of the outbreak reached Peshawar, a council of war was at once held and measures adopted to meet the situation. The same night the Guides started on their march to Delhi. On May 21 of 1857, the 55th Native Infantry rose at Mardan. The majority made an escape across the Indus, only to perish after privations at the hands of the hill-men of the Hazara border. On May 22, warned by this example, the authorities of Peshawar disarmed the 24th, 27th, and 51st Native Infantry. The result being that Pashtuns not only of Peshawar, but also from across the border, came flocking in to join the newly raised levies. The next few months were not without incident, though the crisis was past. When the mutiny was finally suppressed, it was clear that the frontier districts had proved to the British government a source of strength rather than of danger.[18]

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was also a hotbed center of the Indian independence movement. An example of defiance against the Raj was when in 1930, the Khudai Khidmatgars under Abdul Gaffar Khan in conjunction with the Indian National Congress broke out in Peshawar. Soldiers of the Garhwal Rifles were brought in to suppress the protests, but refused to fire on non-violent protests. By disobeying direct orders, the regiment sent a clear message to London that loyalty of India's armed forces could not be taken for granted to enact harsh measures. However, by 1931, 5,000 members of the Khudai Khidmatgar and 2,000 members of the Congress Party were arrested.[23] This was followed by the shooting of unarmed protestors in Utmanzai and the Takkar Massacre followed by the Hathikhel massacre. There were other tensions in the area as well, particularly those that involved agitations by Pashtun tribesmen against the Imperial government. For example, in 1936, a British Indian court ruled against the marriage of a Hindu girl at Bannu who was abducted and forced to convert to Islam. After the girl's family filed a case, the court ruled in the family's favor, angering the local Muslims who had later went on to lead attacks against the Bannu Brigade.[24]

The 15 August 1947 marked the end of the British Raj. In July 1947, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Indian Independence Act 1947 declaring that by 15 August 1947 it would divide British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The act also declared that the fate of the North West Frontier Province would be subject to the result of referendum. This was in accord with the June 3rd Plan proposal to have a referendum to decide the future of the Northwest Frontier Province—to be voted on by the same electoral college as for the Provincial Legislative Assembly in 1946.[25]

The eligible voters was about 16% of the total population equal to that of in 1946 i.e. out of the population of 3.5 million, only 572,799 people were Registered voters. Some have argued that a segment of the population was barred from voting but as compared to the 1946 elections, exercised votes were only 15% less in number.[26]

For some individuals rigging and low voter turnout was a concern in the referendum but the voters that cast a vote were only 15% less(i.e.292,118 voters) than that of 1946 elections (i.e.375,989 voters). Also some argue that the princely states of NWFP and tribal areas were barred from participating in the referendum but the number of eligible voters was same as that of 46 elections.[27]

Post-independence

There had been tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan ever since Afghanistan voted against Pakistan's inclusion in the United Nations in 1948.[28] Afghanistan's loya jirga of 1949 declared the Durand Line invalid. This led to border tensions with Pakistan. Afghanistan's governments have periodically refused to recognize Pakistan's inheritance of British treaties regarding the region.[29]

During the 1950s, Afghanistan supported the Pushtunistan Movement, a secessionist movement that failed to gain substantial support amongst the tribes of the North-West Frontier Province. Afghanistan's refusal to recognize the Durrand Line, and its subsequent support for the Pashtunistan Movement has been cited as the main cause of tensions between the two countries that have existed since Pakistan's independence.[30]

After the Afghan-Soviet War, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has become one of the areas of top focus for the War against Terror. The province has been reported to struggle with the issues of crumbling schools, non-existent healthcare, and lack of any sound infrastructure while areas such as Islamabad and Rawalpindi receive priority funding.[31]

In 2010 the name of the province changed to "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". Protests arose among the local ethnic Hazara population due to this name change, as they began to demand their own province. Seven people were killed and 100 injured in protests on 11 April 2011.[32]

See also

References

- ↑ (Princeton Roadmap to Regents, p. 80)

- 1 2 (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 148)

- ↑ (Bhattacharya, p. 187)

- ↑ (Gupta 1999, p. 199)

- ↑ (Comrie 1990, p. 549)

- ↑ (University of Peshawar:Ancient Pakistan v.3 1967, p. 23)

- ↑ (Bhandarkar, p. 2)

- 1 2 3 4 (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 149)

- ↑ (Faber and Faber, pp. 52–53)

- 1 2 3 (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 150)

- ↑ Buddhism in Central Asia by Baij Nath Puri p.131

- 1 2 (Wynbrandt, pp. 52–54)

- ↑ (Wink, p. 125)

- ↑ (Holt et al 1977, p. 3)

- ↑ (Wynbrandt 2009, pp. 52–55)

- ↑ (Tomsen 2013, p. 56)

- 1 2 3 4 (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 151)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 152)

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 153)

- ↑ (V.Nalwa 2009, p. 102)

- ↑ (V.Nalwa 2009, p. 91)

- ↑ (Imperial Gazetteer, p. 138)

- ↑ (Kazi)

- ↑ (Aboul-Enein & 2013 153)

- ↑ (Pearson, p. 65)

- ↑ (Meyer, p. 107)

- ↑ (Roberts, pp. 108–109)

- ↑ (Kiessling, p. 8)

- ↑ http://www.carnegieendowment.org/files/cp72_grare_final.pdf

- ↑ "'Pashtunistan' Issues Linger Behind Row". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ↑ Underhill, Natasha (2014). Countering Global Terrorism and Insurgency: Calculating the Risk of State Failure in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 195–121. ISBN 978-1-349-48064-7.

- ↑ "Anti-Pakhtunkhwa protest claims 7 lives in Abbottabad". The Statesmen. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

Sources

- Roadmap to the Regents: Global History and Geography. Princeton. ISBN 9780375763120.

- West, Barbara (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing.

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 19– Imperial Gazetteer of India". Digital South Asia Library. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Bhattacharya, Avijeet. Journeys on the Silk Road Through Ages. Zorba Publishers.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa - province, Pakistan". Encylopaedia Britannica.

- Docherty, Patty (2007). The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-1-4027-5696-2.

- Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. New York: Infobase Publishing.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Wink, Andre. Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. E.J Brill.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - P. M. Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge history of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29137-2.

- Nalwa, Vanit (2009). Hari Singh Nalwa – Champion of Khalsaji. New Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- Kazi, Sarwar (20 April 2002). "Qissa Khwani's tale of tear and blood". The Statesman. The Statesman.

- The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1753-0.

- Meyer, Karl E. (5 August 2008). The Dust Of Empire: The Race For Mastery In The Asian Heartland. PublicAffairs – via Google Books.

- Jeffrey J. Roberts. The Origins of Conflict in Afghanistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275978785. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Kiessling, Hein (2016). Faith, Unity, Discipline. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1849045179.

- Gupta, G.S (1999). India:From Indus Valley Civilisation to Mauryas. Concept Publishers. ISBN 81-7022-763-1.

- Comrie, Bernard (1990). The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press.

- Ancient Pakistan: Volume 3. University of Peshawar Dept. of Archaeology. 1967.

- Bhandarkar, D.R. Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture.

- Yousef Aboul-Enein; Basil Aboul-Enein (2013). The Secret War for the Middle East. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1612513096.

- Tomsen, P. (2013). The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-412-3. Retrieved 2018-05-06.