Human nose

| Human nose | |

|---|---|

Human nose in profile | |

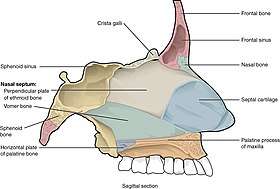

Cross-section of the interior of a nose | |

| Details | |

| Artery | sphenopalatine artery, greater palatine artery |

| Vein | facial vein |

| Nerve | external nasal nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nasus |

| MeSH | D009666 |

| TA |

A06.1.01.001 A01.1.00.009 |

| FMA | 46472 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human nose is the protruding part of the face that bears the nostrils. The shape of the nose is determined by the nasal bones and the nasal cartilages, including the nasal septum which separates the nostrils. On average the nose of a male is larger than that of a female.[1]

The nose has an area of olfactory epithelium, specialised cells responsible for the sense of smell. Another function of the nose is the conditioning of inhaled air, warming and moistening it. Nasal hair in the nostrils prevents large particles from entering the lungs. Sneezing is a reflex to expel unwanted particles from the nose that irritate the nasal mucosa. Sneezing can transmit infections, because it creates aerosols in which the droplets can harbour pathogens.

Structure

The nose is structured on a bony-cartilaginous framework, made up of the nasal bones and nasal cartilages.

The nasal root is the top of the nose, above the bridge and below the glabella, forming an indentation known as the nasion at the frontonasal suture where the frontal bone meets the nasal bones.

The anterior nasal spine is the thin projection of bone at the midline on the lower nasal margin, holding the cartilaginous center of the nose.[2] Adult humans have a high concentration of cilia in the sinus ostia, openings from the paranasal sinuses to the nasal cavity.

Muscles

The movements of the human nose are controlled by groups of facial and neck muscles that are set deep to the skin. There are four interconnected groups in what is known as the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), connected by the superficial aponeurosis. The SMAS covers, invests and forms the terminations of the muscles.

The elevator muscle group includes the procerus muscle that helps to flare the nostrils; and the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle, which lifts the upper lip and the alae.

The depressor muscle group includes the alar nasalis muscle and the depressor septi nasi muscle.

The compressor muscle group includes the transverse nasalis muscle.

The the dilator muscle group includes the dilator naris muscle that expands the nostrils; it is in two parts: (i) the dilator nasi anterior muscle, and (ii) the dilator nasi posterior muscle.

Development

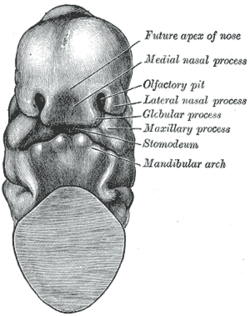

At four weeks, gestational age, the neural crest cells (the precursors of the nose) begin their caudal migration (from the posterior) towards the midface. Two symmetrical nasal placodes (the future olfactory epithelium) develop inferiorly. In the sixth week they invaginate to form two nasal pits. The nasal pits then divide into the medial and the lateral nasal processes (the future upper lip and nose). The medial processes then form the septum, the philtrum, and the premaxilla of the nose; the lateral processes form the sides of the nose; and the mouth forms from the stomodeum (the anterior ectodermal portion of the alimentary tract), which is inferior to the nasal complex.

A nasobuccal membrane separates the mouth from the nose; respectively, the inferior oral cavity (the mouth) and the superior nasal cavity (the nose). As the olfactory pits deepen, said development forms the choanae, the two openings that connect the nasal cavity and the nasopharynx (upper part of the pharynx that is continuous with the nasal passages). Initially, primitive-form choanae develop, which then further develop into the secondary, permanent choanae.

At ten weeks, the cells differentiate into muscle, cartilage, and bone. If this important, early facial embryogenesis fails, it might result in anomalies such as choanal atresia (absent or closed passage), medial nasal clefts (fissures), or lateral nasal clefts, nasal aplasia (faulty or incomplete development), and polyrrhinia (double nose).[3]

This normal, prenatal development is exceptionally important — because the newborn infant breathes through the nose for the first six weeks — thus, when a child is afflicted with bilateral choanal atresia, the blockage of the posterior nasal passage, either by abnormal bony or soft tissue, emergency remedial action is required to ensure that the child can breathe.[4]

Function

The nose plays the major part in the olfactory system. It contains an area of specialised cells, olfactory receptor neurons responsible for the sense of smell.

Another function of the nose is to warm and moisten inhaled air and provide its passage to the respiratory tract. The three positioned nasal conchae in each cavity provide four grooves as air passages, along which the air is circulated and moved to the nasopharynx.

Nasal hair in the nostrils traps large particles preventing their entry into the lungs. Sneezing is an important reflex initiated by irritation of the nasal mucosa to expel unwanted particles through the mouth and nose. Photic sneezing is a reflex brought on by different stimuli such as bright lights.

Clinical significance

One of the most common medical conditions involving the nose are nosebleeds (in medicine: epistaxis). Most of them occur in Kiesselbach's plexus. Nasal congestion is a common symptom of infections or other inflammations of the nasal lining (rhinitis), such as in allergic rhinitis or vasomotor rhinitis (resulting from nasal spray abuse). Most of these conditions also cause anosmia, which is the medical term for a loss of smell. This may also occur in other conditions, for example following trauma, in Kallmann syndrome or Parkinson's disease.

The nose is a common site of foreign bodies. The nose is susceptible to frostbite. Nasal flaring is a sign of respiratory distress that involves widening of the nostrils on inspiration.

Because of the special nature of the blood supply to the human nose and surrounding area, it is possible for retrograde infections from the nasal area to spread to the brain. For this reason, the area from the corners of the mouth to the bridge of the nose, including the nose and maxilla, is known to doctors as the danger triangle of the face.

Specific systemic diseases, infections or other conditions that may result in destruction of part of the nose (for example, the nasal bridge, or nasal septal perforation) are rhinophyma, skin cancer (for example, basal cell carcinoma), granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, syphilis, leprosy and exposure to cocaine, chromium or toxins. The nose may be stimulated to grow in acromegaly.

The surgical procedure to correct breathing problems due to disorders in the nasal structures is called a rhinoplasty, and this is also the procedure used for a cosmetic surgery when it is commonly called a "nose job". For surgical procedures of rhinoplasty the nose is mapped out into a number of subunits and segments. This uses nine aesthetic nasal subunits and six aesthetic nasal segments.

Some drugs can be administered nasally. Nasal administration can include nasal sprays and topical treatments.

Society and culture

Some people choose to have cosmetic surgery called a rhinoplasty, to change the appearance of their nose. Nose piercings are also common, such as in the nostril, septum or bridge.

In New Zealand, nose pressing ("hongi") is a traditional greeting originating among the Māori people.[5] However it is now generally confined to certain traditional celebrations.[6]

The Hanazuka monument enshrines the mutilated noses of at least 38,000 Koreans killed during the Japanese invasions of Korea from 1592 to 1598.[7]

The septal cartilage of the nose can be destroyed through repeated nasal inhalation of drugs such as cocaine. This in turn can lead to more widespread collapse of the nasal skeleton.

Nose-picking is a common, mildly taboo habit. Medical risks include the spread of infections, nosebleeds and, rarely, self-induced perforation of the nasal septum. The wiping of the nose with the hand, commonly referred to as the "allergic salute", is also mildly taboo and can result in the spreading of infections as well. Habitual as well as fast or rough nose wiping may also result in a crease (known as a transverse nasal crease or groove) running across the nose, and can lead to permanent physical deformity observable in childhood and adulthood.[8][9]

Nose fetishism (or nasophilia) is the sexual fetish (or paraphilia) for the nose. The psychiatric condition of extreme nose picking is termed rhinotillexomania.

In certain Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand and Bangladesh rhinoplasty is common to create a more developed nose bridge or "high nose".[10][11][12] Similarly, "DIY nose lifts" in the form of re-usable cosmetic items have become popular and are sold in many Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Sri Lanka and Thailand.[13][14][15] A high-bridged nose has been a common beauty ideal in many Asian cultures dating back to the beauty ideals of ancient China and India.[16][17]

Evolutionary hypotheses

Neanderthals

Clive Finlayson of the Gibraltar Museum said the large Neanderthal noses were an adaption to the cold,[18] Todd C. Rae of the American Museum of Natural History said primate and arctic animal studies have shown sinus size reduction in areas of extreme cold rather than enlargement in accordance with Allen's rule.[19] Therefore, Todd C. Rae concludes that the design of the large and prognathic Neanderthal nose was evolved for the hotter climate of the Middle East and was kept when the Neanderthals entered Europe.[19]

Miquel Hernández of the Department of Animal Biology at the University of Barcelona said the "high and narrow nose of Eskimos" and "Neanderthals" is an "adaption to a cold and dry environment", since it contributes to warming and moisturizing the air and the "recovery of heat and moisture from expired air".[20]

Humans

An article published in the speculative journal Medical Hypotheses suggested that the nose is an alteration of the angle of skull following human skeletal changes due to bipedalism. This changed the shape of the skull base causing, together with change in diet, a knock-on morphological reduction in the relative size of the maxillary and mandible and through this a "squeezing" of the protrusion of the most anterior parts of the face more forward and so increasing nose prominence and modifying its shape.[21]

The aquatic ape hypothesis relates the nose to a hypothesized period of aquatic adaptation in which the downward-facing nostrils and flexible philtrum prevented water from entering the nasal cavities.[22] The theory is not generally accepted by mainstream scholars of human evolution.[23]

Neoteny

Stephen Jay Gould has noted that larger noses are less neotenous, especially the large "Grecian" nose.[24] Women have smaller noses than men due to not having increased secretion of testosterone in adolescence.[1] Smaller noses, along with other neotenous features such as large eyes and full lips, are generally considered more attractive on women.[25] Werner syndrome, a condition that causes the appearance of premature aging, causes a "bird-like" appearance due to pinching of the nose[26] while, conversely, Down syndrome, a neotenizing condition,[27] causes flattening of the nose.[28]

See also

- Anatomy of the human nose

- Empty nose syndrome, a nose crippled by excessive resection of the inferior and/or middle turbinates of the nose

- Nasal sebum, the greasy substance on the outer part of the nose

- Nasothek

- Neti (Hatha Yoga), an Ayurvedic technique of nasal cleansing

- Sròn, the Scottish Gaelic word for nose and the name of some hills in the Scottish Highlands

References

- 1 2 Jean-Baptiste de Panafieu, P. (2007). Evolution. Seven Stories Press, USA.

- ↑ "Glossary: nasal spine (anterior)". ArchaeologyInfo.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-01. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ↑ Hengerer AS, Oas RE (1987). Congenital Anomalies of the Nose: Their Embryology, Diagnosis, and Management (SIPAC). Alexandria VA: American Academy of Otolaryngology.

- ↑ Nasal Anatomy at eMedicine

- ↑ Derby, Mark (September 2013). "Ngā mahi tika". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ "Greetings! Hongi Style! – polynesia.com | blog". polynesia.com | blog. 2016-03-24. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2017-09-18.

- ↑ Sansom, George; Sir Sansom; George Bailey (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford studies in the civilizations of eastern Asia. Stanford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

Visitors to Kyoto used to be shown the Minizuka or Ear Tomb, which contained, it was said, the noses of those 38,000, sliced off, suitably pickled, and sent to Kyoto as evidence of victory.

- ↑ Pray, W. Steven (2005). Nonprescription Product Therapeutics. p. 221: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0781734983.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved 2012-11-25. White Line on Nose in Children

- ↑ "Rhinoplasty - Reshaping of the nose". 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016.

- ↑ "Korean Rhinoplasty (Nose Surgery)". Archived from the original on 2016-04-07.

- ↑ "Miss Universe Malaysia pageant contestants 'look too western'". Archived from the original on 2016-09-22.

- ↑ Strochlic, Nina (6 January 2014). "DIY Plastic Surgery: Can You Change Your Face Without Going Under the Knife?" – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- ↑ "PressReader.com - Connecting People Through News". www.pressreader.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06.

- ↑ "NOSE SHAPER, shybuy.lk". shybuy.lk. Archived from the original on 2017-06-05.

- ↑ Marc S. Abramson (2011). Ethnic Identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-8122-0101-9. Archived from the original on 2018-05-02.

- ↑ Johann Jakob Meyer (1989). Sexual Life in Ancient India: A Study in the Comparative History of Indian Culture. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 433. ISBN 978-81-208-0638-2. Archived from the original on 2018-05-02.

- ↑ Finlayson, C (2004). Neanderthals and modern humans: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84. ISBN 0-521-82087-1.

- 1 2 Rae, T.C. (2011). "The Neanderthal face is not cold adapted". Journal of Human Evolution. 60 (2): 234–239. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.10.003. PMID 21183202.

- ↑ Hernández, M.; Fox, C. L.; Garcia-Moro, C. (1997). "Fueguian cranial morphology: The adaptation to a cold, harsh environment". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 103: 103–117. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199705)103:1<103::AID-AJPA7>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 9185954.

- ↑ Mladina, R; Skitarelić N; Vuković K (2009). "Why do humans have such a prominent nose? The final result of phylogenesis: a significant reduction of the splanchocranium on account of the neurocranium". Med Hypotheses. 73 (3): 280–3. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.03.045. PMID 19442453.

- ↑ Morgan, Elaine (1997). The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. Souvenir Press. ISBN 0-285-63518-2.

- ↑ Meier, R (2003). The complete idiot's guide to human prehistory. Alpha Books. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-02-864421-2.

- ↑ Gould, S.J. (1996). The mismeasure of man. Norton and Company: NY.

- ↑ Jones, Doug (1995). "Sexual Selection, Physical Attractiveness, and Facial Neoteny: Cross-cultural Evidence and Implications". Current Anthropology. 36 (5): 723–48. doi:10.1086/204427. JSTOR 2744016.

- ↑ Leistritz, F. NCBI. Werner Syndrome. Retrieved Jun 2, 2011, from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ Opitz, John M.; Gilbert-Barness, Enid F. (2005). "Reflections on the pathogenesis of Down syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 37: 38–51. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320370707. PMID 2149972.

- ↑ Fuente: Series de porcentajes obtenidas en un amplio estudio realizado por el CMD (Centro Médico Down) de la Fundación Catalana del Síndrome de Down Archived 2011-05-28 at the Wayback Machine., sobre 796 personas con SD. Estudio completo en Josep M. Corretger et al (2005). Síndrome de Down: Aspectos médicos actuales. Ed. Masson, para la Fundación Catalana del Síndrome de Down. ISBN 84-458-1504-0. Pag. 24–32.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human noses. |

| Look up WikiSaurus:nose in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |