Ureter

| Ureter | |

|---|---|

| |

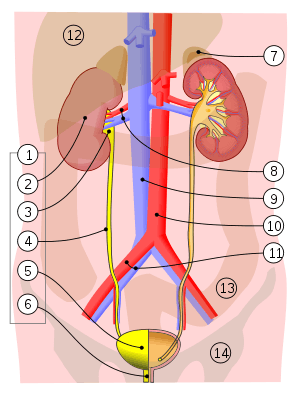

1. Human urinary system: 2. Kidney, 3. Renal pelvis, 4. Ureter, 5. Urinary bladder, 6. Urethra. (Left side with frontal section), 7. Adrenal gland Vessels: 8. Renal artery and vein, 9. Inferior vena cava, 10. Abdominal aorta, 11. Common iliac artery and vein With transparency: 12. Liver, 13. Large intestine, 14. Pelvis | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Ureteric bud |

| System | Urinary system |

| Artery | Superior vesical artery, Vaginal artery, Ureteral branches of renal artery |

| Nerve | Ureteric plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Ureter |

| MeSH | D014513 |

| TA | A08.2.01.001 |

| FMA | 9704 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

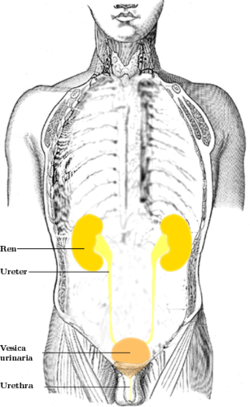

In human anatomy, the ureters are tubes made of smooth muscle fibers that propel urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. In the adult, the ureters are usually 25–30 cm (10–12 in) long and around 3–4 mm (0.12–0.16 in) in diameter. Histologically, the ureter is lined by the urothelium, a type of transitional epithelium, and has an additional smooth muscle layer in the more distal one-third to assist with peristalsis.

Structure

In humans, the ureters arise from the pelvis of each kidney, and descend on top of the psoas major muscle to reach the brim of the pelvis. Here, they cross in front of the common iliac arteries. They then pass down along the sides of the pelvis, and finally curve forwards and enter the bladder from its left and right sides at the back of the bladder.[1]:324–326 This is classically depicted as running "posteroinferiorly on the lateral walls of the pelvis and then curve anteromedially to enter the bladder". The orifices of the ureters are placed at the postero-lateral angles of the trigone of the bladder, and are usually slit-like in form. In the contracted bladder they are about 25 mm (1 in) apart and about the same distance from the internal urethral orifice; in the distended bladder these measurements may be increased to about 50 mm (2 in).

The f unction between the pelvis of the kidney and the ureters is known as the ureteropelvic junction or ureteral pelvic junction, and the junction between the ureter and the bladder is known as the ureterovesical (ureter-bladder) junction. At the entrance to the bladder, the ureters are surrounded by valves known as ureterovesical valves, which prevent vesicoureteral reflux (backflow of urine).

In females, the ureters pass through the mesometrium and under the uterine arteries on the way to the urinary bladder.

The ureter has a diameter of 3 mm (0.12 in) but there are three constrictions, which are the most common sites of renal calculus obstruction:

- at the pelvi-ureteric junction (PUJ) of the renal pelvis and the ureter

- as the ureter enters the pelvis and crosses over the common iliac artery bifurcation

- at the vesicoureteric junction (VUJ) as the ureter obliquely enters the bladder wall

Blood supply

The ureters has an arterial supply which varies along its course.[1]:324–326

- The upper part of the ureter closest to the kidney is supplied by the renal arteries

- The middle part of the ureter is supplied by the common iliac arteries, direct branches from the abdominal aorta, and gonadal arteries (the testicular artery in men or ovarian artery in women)

- The lower part of the ureter closest to the bladder is supplied by branches from the internal iliac arteries,[1]:324–326 as well as:

- Superior vesical artery

- Uterine artery (in women only)

- Middle rectal artery

- Vaginal arteries (in women only)

- Inferior vesical artery (in men only)

Within the periureteral adventitia these arteries extensively anastomose thus permitting surgical mobilization of the ureter without compromising the vascular supply as long as the adventitia is not stripped. Lymphatic and venous drainage mostly parallels that of the arterial supply.[2]

Nerve supply

The ureters are richly innervated by nerves that travel alongside the blood vessels, building the ureteric plexus.[3] The primary sensation to the ureters is provided by nerves that come from T12-L2 segments of the spinal cord. Thus pain may be referred to the dermatomes of T12-L2, namely the back and sides of the abdomen, the scrotum (males) or labia majora (females) and upper part of the front of the thigh.[1]:324–326

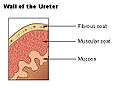

Microanatomy

The ureter is lined by urothelium, a type of transitional epithelium that is capable of responding to stretches in the ureters. The transitional epithelium may appear as a columnar epithelia when relaxed, and squamous epithelia when distended. Below the epithelium, a Lamina Propria exists. The Lamina Propria is made up of loose connective tissue with many elastic fibers interspersed with blood vessels, veins and lymphatics. The ureter is surrounded by two muscular layers, an inner longitudinal layer of muscle, and an outer circular or spiral layer of muscle.[4]:324

View of the ureter under the microscope

View of the ureter under the microscope Wall of the ureter

Wall of the ureter

Development

During the embryologic development of the kidney, the ureteropelvic junction is the last part of the ureter to become patent.

Function

The ureters are a component of the urinary system. Urine, produced by the kidneys, travels along the ureters to the bladder.

Ultrasound showing a jet of urine entering the bladder (large black section) through the ureter.

Ultrasound showing a jet of urine entering the bladder (large black section) through the ureter.

Clinical significance

Cancer of the ureters is known as ureteral cancer.

Failure of the ureteropelvic junction to become patent during development is the most frequent cause of bilateral hydronephrosis, particularly in male neonates. Pyeloplasty, which involves excision of the stenotic section and creation of a new junction, is the most common and effective treatment for this problem.

Injury

Injuries to the ureter with certain forms of trauma including penetrating abdominal injuries and injuries at high speeds followed by an abrupt stop (e.g., a high speed car accident).[5] The ureter is injured in 0.2 per 1,000 cases of vaginal hysterectomies and 1.3 per 1,000 cases of abdominal hysterectomies,[6] near the infundibulopelvic (suspensory) ligament or where the ureter courses posterior to the uterine vessels.[7]

Ureteral stones

A kidney stone can move from the kidney and become lodged inside the ureter, which can block the flow of urine, as well as cause a sharp cramp in the back, side, or lower abdomen.[8] The affected kidney could then develop hydronephrosis, should a part of the kidney become swollen due to blocked flow of urine.[9] There are three sites where a kidney stone will commonly become stuck:

- at the ureteric junction of renal pelvis;

- as the ureter passes over the iliac vessels;

- where the ureter enters into the urinary bladder (vesicoureteric junction).

Reflux

Vesicoureteral reflux refers to the reflux of fluid from the bladder to the ureters during urination. This condition can be one cause of chronic urinary tract infections, particularly in children. It is unclear if there is a role of surgery in vesicoureteral reflux.[10]

Other animals

Ureters are also found in all other amniote species, although different ducts fulfill the same role in amphibians and fish.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2005). Gray's Anatomy for Students. Illustrated by Richardson, Paul. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Wein, Alan J. (2011). Campbell-Walsh Urology (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 31.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Dudeck, Ronald W. (2007). High-Yield Kidney. High-Yield Systems (1st ed.). Lippincott Willams and Wilkins. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7817-5569-6.

- ↑ Lowe, Alan Stevens, James S. (2005). Human histology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia & Toronto: Elsevier Mosby. ISBN 0-3230-3663-5.

- ↑ Stein, D. M.; Santucci, R. A. (July 2015). "An update on urotrauma". Current Opinion in Urology. 25 (4): 323–30. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000184. PMID 26049876.

- ↑ Burks, F. N.; Santucci, R. A. (June 2014). "Management of iatrogenic ureteral injury". Therapeutic Advances in Urology. 6 (3): 115–24. doi:10.1177/1756287214526767. PMC 4003841. PMID 24883109.

- ↑ Santucci, Richard A. "Ureteral Trauma". Medscape. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Symptoms of Kidney Stones". MedicalBug. 1 January 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ Resnick, Martin I.; Lam, Mildred; Zipp, Thomas (4 September 2009). "Kidney Stones". NetWellness. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ Najar, M. S.; Saldanha, C. L.; Banday, K. A. (October 2009). "Approach to urinary tract infections". Indian Journal of Nephrology. 19 (4): 129–139. doi:10.4103/0971-4065.59333. ISSN 0971-4065. PMC 2875701. PMID 20535247.

- ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 378. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.