Hepatitis E

| Hepatitis E | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hepatitis E virus | |

| Specialty |

Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Nausea, jaundice[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test[1] |

| Treatment | Rest, Ribavirin(if chronic)[1] |

| Frequency | 28 million (2013)[2] |

Hepatitis E is inflammation of the liver caused by infection with the hepatitis E virus.[3] It is one of five known human hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E. HEV is a positive-sense, single-stranded, nonenveloped, RNA icosahedral virus; HEV has a fecal-oral transmission route.[4][5] Infection with this virus was first documented in 1955 during an outbreak in New Delhi, India.[6] A preventive vaccine (HEV 239) is approved for use in China.[7]

Although hepatitis E often causes an acute and self-limiting infection (the viral infection is temporary and the individual recovers) with low death rates in the western world, it bears a high risk of developing chronic hepatitis in people with a weakened immune system with substantially higher death rates. Organ transplant recipients who receive medications to weaken the immune system and prevent organ rejection are thought to be the main population at risk for chronic hepatitis E.[8] Furthermore, in healthy individuals during the duration of the infection, the disease severely impairs a person’s ability to work, care for family members, and perform other daily activities. Hepatitis E occasionally develops into an acute, severe liver disease, and is fatal in about 2% of all cases.

Clinically, it is comparable to hepatitis A, but in pregnant women, the disease is more often severe and is associated with a clinical syndrome called fulminant liver failure. Pregnant women, especially those in the third trimester, have a higher rate of death from the disease of around 20%.[9]

Hepatitis E newly infected about 28 million people in 2013.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Acute infection

The incubation period of hepatitis E varies from 3 to 8 weeks. After a short prodromal phase symptoms lasting from days to weeks follow. They may include jaundice, fatigue, and nausea. The symptomatic phase coincides with elevated hepatic aminotransferase levels.[10]

Viral RNA becomes detectable in stool and blood serum during incubation period. Serum IgM and IgG antibodies against HEV appear just before onset of clinical symptoms. Recovery leads to virus clearance from the blood, while the virus may persist in stool for much longer. Recovery is also marked by disappearance of IgM antibodies and increase of levels of IgG antibodies.[5][10]

Chronic infection

While usually an acute disease, in immunocompromised subjects—particularly in solid organ transplant patients—hepatitis E may cause a chronic infection.[11] Occasionally this may cause liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.[12]

Other organs

Infection with hepatitis E virus can also lead to problems in other organs. For some of these reported conditions the relationship is tenuous, but for several neurological and blood conditions the relationship appears causal:[13]

- Acute pancreatitis

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (acute limb weakness due to nerve involvement) and neuralgic amyotrophy (arm and shoulder weakness)

- Hemolytic anemia in people with the hereditary risk factor glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD deficiency)

- Glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome and/or cryoglobulinemia

- Mixed cryoglobulinemia, where antibodies in the bloodstream react inappropriately at low temperatures

- Severe thrombocytopenia (low platelet count in the blood) which confers a risk of dangerous bleeding

Infection in pregnancy

Pregnant women show a more severe course of infection than other populations. Mortality rates of 20% to 25% and hepatic failure have been reported from outbreaks of genotype 1 HEV in developing countries. Besides signs of an acute infections, adverse maternal and fetal outcomes may include preterm delivery, abortion, stillbirth, and intrauterine fetal and neonatal death.[14][15] Reports about infection of pregnant women with genotype 3 HEV in industrialized countries do exist, but do not report comparable severe outcomes.

The pathologic and biologic mechanisms behind the adverse outcomes of pregnancy infections remain largely unclear so far. Mainly, increased viral replication and influence of hormonal changes on the immune system have been discussed lately.[16] Furthermore, studies showing evidence for viral replication in the placenta[17] or reporting the full viral life cycle in placental-derived cells in vitro implicate the human placenta as site of extra-hepatic replication.

Virology

Classification

Only one serotype of the virus is known, and classification is based on the nucleotide sequences of the genome.[18] Genotype 1 has been classified into five subtypes, genotype 2 into two subtypes, and genotypes 3 and 4 have been into 10 and seven subtypes, respectively.Differences have been noted between the different genotypes. For genotype 1, the age at which incidence peaks is between 15 and 35 years and mortality is about 1%. Genotypes 3 and 4—the most common in Japan—are more common in people older than 60 years and the mortality is between 5 and 10%.

Distribution

- Genotype 1 has been isolated from tropical and several subtropical countries in Asia and Africa.[19]

- Genotype 2 has been isolated from Mexico, Nigeria, and Chad.[20]

- Genotype 3 has been isolated almost worldwide including Asia, Europe, Oceania, and North and South America.[21]

- Genotype 4 appears to be limited.[19]

Genotypes 1 and 2 are restricted to humans and often associated with large outbreaks and epidemics in developing countries with poor sanitation conditions.[19] Genotypes 3 and 4 infect humans, pigs, and other animal species and have been responsible for sporadic cases of hepatitis E in both developing and industrialized countries.[22]

In the United Kingdom, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said that the number of human hepatitis E cases increased by 39% between 2011 and 2012.[23]

Transmission

Hepatitis E is widespread in Southeast Asia, northern and central Africa, India, and Central America.[24] It is spread mainly by the fecal-oral route due to fecal contamination of water supplies or food; person-to-person transmission is uncommon.[25]

The incubation period following exposure to the hepatitis E virus ranges from 3 to 8 weeks, with a mean of 40 days.[25] Outbreaks of epidemic hepatitis E most commonly occur after heavy rainfalls and monsoons because of their disruption of water supplies.[26] Major outbreaks have occurred in New Delhi, India (30,000 cases in 1955–1956),[27] Burma (20,000 cases in 1976–1977),[28] Kashmir, India (52,000 cases in 1978),[29] Kanpur, India (79,000 cases in 1991),[27] and China (100,000 cases between 1986 and 1988).[30]

DEFRA said that evidence indicated the increase in hepatitis E in the UK was due to food-borne zoonoses, citing a study that found 10% of pork sausages on sale in the UK contained the virus. Some research suggests that food must reach a temperature of 70 °C for 20 minutes to eliminate the risk of infection. An investigation by the Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency found hepatitis E in 49% of pigs in Scotland.[23]

Hepatitis E infection appeared to be more common in people on hemodialysis, although specific risk factors for transmission is not clear.[31]

Animal reservoir

The disease is thought to be a zoonosis in that animals are thought to be the source. Both deer and swine have been implicated.[32] Domestic animals have been reported as a reservoir for the hepatitis E virus, with some surveys showing infection rates exceeding 95% among domestic pigs.[33] Replicative virus has been found in the small intestine, lymph nodes, colon, and liver of experimentally infected pigs. Transmission after consumption of wild boar meat and uncooked deer meat has been reported, as well.[34] The rate of transmission to humans by this route and the public health importance of this are, however, still unclear.[35]

A number of other small mammals have been identified as potential reservoirs: the lesser bandicoot rat (Bandicota bengalensis), the black rat (Rattus rattus brunneusculus) and the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus). A new virus designated rat hepatitis E virus has been isolated.[36]

A rabbit hepatitis E virus has been described,[37] with a study published in 2014 showing that research rabbits from two different American vendors showed seroprevalences of 40% for supplier A and 50% for supplier B when testing for antibodies against hepatitis E virus (HEV). Supplier A was a conventional rabbit farm, and supplier B was a commercial vendor of specific pathogen-free research rabbits. The study remarks, "HEV probably is widespread in research rabbits, but effects on research remain unknown." Laboratory animal care personnel, researchers, and support staff represent a new population at risk for HEV infection, and research facilities should be diligent in measures to prevention of this possibly zoonotic pathogen.[38]

An avian virus has been described that is associated with hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome in chickens. This virus is genetically and antigenically related to mammalian HEV, and probably represents a new genus in the family.[39]

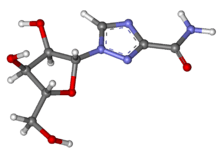

Genomics

The virus has since been classified into the genus Orthohepevirus, and has been reassigned into the Hepeviridae family. The virus itself is a small nonenveloped particle.The genome is about 7200 bases in length, is a polyadenylated, single-strand RNA molecule that contains three discontinuous and partially overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) along with 5' and 3' cis-acting elements, which have important roles in HEV replication and transcription. ORF1 encodes a methyltransferase, protease, helicase and replicase; ORF2 encodes the capsid protein and ORF3 encodes a protein of undefined function. A three-dimensional, atomic-resolution structure of the capsid protein in the context of a virus-like particle has been described.[40][41]

As of 2009, around 1,600 sequences of both human and animal isolates of HEV are available in open-access sequence databases. Species of this genus infect humans, pigs, boars, deer, rats, rabbits, and birds.[42]

Virus lifecycle

The lifecycle of hepatitis E virus is unknown; the capsid protein obtains viral entry by binding to a cellular receptor. ORF2 (c-terminal) moderates viral entry by binding to HSC70.

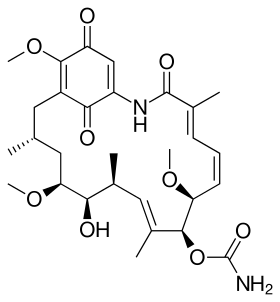

Geldanamycin blocks the transport of HEV239 capsid protein, but not the binding/entry of the truncated capsid protein, which indicates that HSP90 plays an important part in HEV transport.[40]

Diagnosis

In terms of the diagnosis of hepatitis E, only a laboratory test that confirms antibodies present for HEV RNA or HEV can be trusted as conclusive for the virus in any individual tested for it.[43][44]

Prevention

Sanitation

Sanitation is the most important measure in prevention of hepatitis E; this consists of proper treatment and disposal of human waste, higher standards for public water supplies, improved personal hygiene procedures, and sanitary food preparation. Thus, prevention strategies of this disease are similar to those of many others that plague developing nations.[25]

Vaccines

A vaccine based on recombinant viral proteins was developed in the 1990s and tested in a high-risk population (in Nepal) in 2001.[45] The vaccine appeared to be effective and safe, but development was stopped for lack of profitability, since hepatitis E is rare in developed countries.[46] No hepatitis E vaccine is licensed for use in the United States.[47]

Although other HEV vaccine trials have been successful, these vaccines have not yet been produced or made available to susceptible populations. The exception is China; after more than a year of scrutiny and inspection by China's State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA), a hepatitis E vaccine developed by Chinese scientists was available at the end of 2012. The vaccine—called HEV 239 by its developer Xiamen Innovax Biotech—was approved for prevention of hepatitis E in 2012 by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, following a controlled trial on 100,000+ people from Jiangsu Province where none of those vaccinated became infected during a 12-month period, compared to 15 in the group given placebo.[48] The first vaccine batches came out of Innovax' factory in late October 2012, to be sold to Chinese distributors.[46]

Due to the lack of evidence, WHO as of 2015 did not make a recommendation regarding routine use of the HEV 239 vaccine.[49] National authorities may however, decide to use the vaccine based on the local epidemiology.[49]

Treatment

In terms of treatment, ribavirin is not registered for hepatitis E treatment, though off-label experience for treating chronic hepatitis E with this compound exists. The use of low doses of ribavirin over a three-month period has been associated with viral clearance in about two-thirds of chronic cases. Other possible treatments include pegylated interferon or a combination of ribavirin and pegylated interferon. In general, chronic HEV infection is associated with immunosuppressive therapies, but remarkably little is known about how different immunosuppressants affect HEV infection. In individuals with solid-organ transplantation, viral clearance can be achieved by temporal reduction of the level of immunosuppression.[50][51]

Epidemiology

The hepatitis E virus causes around 20 million infections a year. These result in around three million acute illnesses and as of 2010, 57,000 deaths annually.[52] It is particularly dangerous for pregnant women, who can develop an acute form of the disease that is lethal in 30% of cases or more. HEV is a major cause of illness and of death in the developing world and disproportionate cause of deaths among pregnant women. Hepatitis E is endemic in Central Asia, while Central America and the Middle East have reported outbreaks.[53] Increasingly, hepatitis E is being seen in developed nations, with reports in 2005 of 329 cases of hepatitis E virus infection in England and Wales.[54]

Recent outbreaks

In 2004, two outbreaks occurred, both of them in sub-Saharan Africa. An outbreak in Chad had several cases with fatalities.[55] The second was in Sudan also with several fatalities.[56] In October 2007, an epidemic of hepatitis E was suspected in Kitgum District of northern Uganda where no previous epidemics had been documented. This outbreak progressed to become one of the largest hepatitis E outbreaks in the world. By June 2009, the epidemic had caused illness in 10,196 persons and 160 deaths.[57] In 2011, a minor outbreak was reported in Tangail, a neighborhood of Dhaka, Bangladesh.[58]

In July 2012, an outbreak was reported in South Sudanese refugee camps in Maban County near the Sudan border. South Sudan's Ministry of Health reported over 400 cases and 16 fatalities as of September 13, 2012.[59] Progressing further, as of February 2, 2013, 88 died due to the outbreak. The medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres said it treated almost 4,000 patients.[60]

In April 2014, an outbreak in the Biratnagar Municipality of Nepal resulted in infection of over 6,000 locals and at least 9 dead.[61]An outbreak was reported in Namibia in January 2018. Two mothers are dead and the total infected is reported as 490.[62]

History

The most recent common ancestor of hepatitis E evolved between 536 and 1344 years ago.[42] It diverged into two clades — an anthropotropic form and an enzootic form — which subsequently evolved into genotypes 1 and 2 and genotypes 3 and 4, respectively. The divergence dates for the various genotypes are as follows: Genotypes 1/2 367–656 years ago; Genotypes 3/4 417–679 years ago. For the most recent common ancestor of the various viruses themselves: Genotype 1 between 87 and 199 years ago; Genotype 3 between 265 and 342 years ago; and Genotype 4 between 131 and 266 years ago. The anthropotropic strains (genotype 1 and 2) have evolved more recently than the others, suggesting that this virus was originally a zooenosis. A study of genotype 3 has suggested that it evolved 320 years ago (95% HPD: 420 – 236 years ago) and that two main subtypes occur.[63]

The use of an avian strain confirmed the proposed topology of the genotypes 1–4 and suggested that the genus may have evolved 1.36 million years ago (range 0.23 million years ago to 2.6 million years ago).[42]

Genotypes 1, 3, and 4 all increased their effective population sizes in the 20th century.[42] The population size of genotype 1 increased noticeably in the last 30–35 years. Genotypes 3 and 4 population sizes began to increase in the late 19th century up to 1940–1945. Genotype 3 underwent a subsequent increase in population size until the 1960s. Since 1990, both genotypes' population sizes have been reduced back to levels last seen in the 19th century. The overall mutation rate for the genome has been estimated at roughly 1.4×10−3 substitutions/site/year.[42]

See also

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the CDC as cited

- 1 2 3 "Hepatitis E | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- 1 2 Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ↑ "Hepatitis E". www.niaid.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ "WHO | What is hepatitis?". www.who.int. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 "Hepatitis E". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Subrat, Kumar (2013). "Hepatitis E virus: the current scenario". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 17 (4): e228–e233. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.11.026. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Li, Shao-Wei; Zhao, Qinjian; Wu, Ting; Chen, Shu; Zhang, Jun; Xia, Ning-Shao (2015-02-25). "The development of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine HEV 239". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 11 (4): 908–914. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1008870. ISSN 2164-5515. PMC 4514148. PMID 25714510.

- ↑ Zhou X, de Man RA, de Knegt RJ, Metselaar HJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q.; De Man; De Knegt; Metselaar; Peppelenbosch; Pan (2013). "Epidemiology and management of chronic hepatitis E infection in solid organ transplantation: a comprehensive literature review". Rev Med Virol. 23 (5): 295–304. doi:10.1002/rmv.1751. PMID 23813631.

- ↑ WHO. "Global Alert and Response (GAR); Hepatitis E". Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- 1 2 Hoofnagle, J. H.; Nelson, K. E.; Purcell, R. H. (2012). "Hepatitis E". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (13): 1237–1244. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1204512. PMID 23013075. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Bonnet, D.; Kamar, N.; Izopet, J.; Alric, L. (2012). "L'hépatite virale E : Une maladie émergente". La Revue de Médecine Interne. 33 (6): 328–334. doi:10.1016/j.revmed.2012.01.017. PMID 22405325.

- ↑ Behrendt, Patrick; Steinmann, Eike; Manns, Michael P.; Wedemeyer, Heiner (2014-12-01). "The impact of hepatitis E in the liver transplant setting". Journal of Hepatology. 61 (6): 1418–1429. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.047.

- ↑ Bazerbachi, F; Haffar, S; Garg, SK; Lake, JR (February 2016). "Extra-hepatic manifestations associated with hepatitis E virus infection: a comprehensive review of the literature". Gastroenterology report. 4 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1093/gastro/gov042. PMC 4760069. PMID 26358655.

- ↑ Kumar A., Beniwal M., Kar P., Sharma J.B., Murthy N.S. (2004). "Wiley Online Library". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 85 (3): 240–244. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.11.018.

- ↑ Patra, Sharda; Kumar, Ashish; Trivedi, Shubha Sagar; Puri, Manju; Sarin, Shiv Kumar (2007-07-03). "Maternal and Fetal Outcomes in Pregnant Women with Acute Hepatitis E Virus Infection". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (1): 28. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00005. ISSN 0003-4819.

- ↑ Pérez-Gracia, María Teresa; Suay-García, Beatriz; Mateos-Lindemann, María Luisa (2017-05-01). "Hepatitis E and pregnancy: current state". Reviews in Medical Virology. 27 (3): n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/rmv.1929. ISSN 1099-1654.

- ↑ Bose, Purabi Deka; Das, Bhudev Chandra; Hazam, Rajib Kishore; Kumar, Ashok; Medhi, Subhash; Kar, Premashis (2014). "Evidence of extrahepatic replication of hepatitis E virus in human placenta". Journal of General Virology. 95 (6): 1266–1271. doi:10.1099/vir.0.063602-0.

- ↑ Pérez-Gracia, María Teresa; García, Mario; Suay, Beatriz; Mateos-Lindemann, María Luisa (2015-06-28). "Current Knowledge on Hepatitis E". Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology. 3 (2): 117–126. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2015.00009. ISSN 2225-0719. PMC 4548356. PMID 26355220.

- 1 2 3 Song, Yoon-Jae (2010-11-01). "Studies of hepatitis E virus genotypes". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 132 (5): 487–488. ISSN 0971-5916. PMC 3028963. PMID 21149996.

- ↑ Pelosi, E; Clarke, I (2008-11-07). "Hepatitis E: a complex and global disease". Emerging Health Threats Journal. 1: e8. doi:10.3134/ehtj.08.008. ISSN 1752-8550. PMC 3167588. PMID 22460217.

- ↑ Hepatitis!E!Vaccine!Working!Group (2012). "Hepatitis(E:(epidemiology(and(disease(burden" (PDF). WHO. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Meng, X. J. (2010-01-27). "Hepatitis E virus: Animal Reservoirs and Zoonotic Risk". Veterinary microbiology. 140 (3–4): 256–65. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.017. ISSN 0378-1135. PMC 2814965. PMID 19361937.

- 1 2 Doward, Jamie (21 September 2013). "Chefs fight for the right to serve their pork pink". The Observer newspaper. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Liu, Dongyou (2010-11-23). Molecular Detection of Human Viral Pathogens. CRC Press. p. 102. ISBN 9781439812372.

- 1 2 3 "Hepatitis E Fact sheet".

- ↑ Griffiths, Jeffrey; Maguire, James H.; Heggenhougen, Kristian; Quah, Stella R. (2010-03-09). Public Health and Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. ISBN 9780123815071. Google books has no page

- 1 2 Bitton, Gabriel (2005-05-27). Wastewater Microbiology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 132. ISBN 9780471717911.

- ↑ Hubálek, Zdenek; Rudolf, Ivo (2010-11-25). Microbial Zoonoses and Sapronoses. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 189. ISBN 9789048196579.

- ↑ Khuroo, Mohammad Sultan (2011-10-01). "Discovery of hepatitis E: The epidemic non-A, non-B hepatitis 30 years down the memory lane". Virus Research. Hepatitis E Viruses. 161 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.007. PMID 21320558. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

- ↑ Cowie, Benjamin C.; Adamopoulos, Jim; Carter, Karen; Kelly, Heath (2005-03-01). "Hepatitis E Infections, Victoria, Australia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (3): 482–484. doi:10.3201/eid1103.040706. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3298235. PMID 15757573.

- ↑ Haffar, Samir; Bazerbachi, Fateh (2017-09-04). "Systematic review with meta-analysis: the association between hepatitis E seroprevalence and haemodialysis". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 46 (9): 790–799. doi:10.1111/apt.14285. PMID 28869287.

- ↑ Pavio, Nicole; Meng, Xiang-Jin; Renou, Christophe (2010-01-01). "Zoonotic hepatitis E: animal reservoirs and emerging risks". Veterinary Research. 41 (6): 46. doi:10.1051/vetres/2010018. ISSN 0928-4249. PMC 2865210. PMID 20359452.

- ↑ Satou K, Nishiura H; Nishiura (2007). "Transmission Dynamics of Hepatitis E Among Swine: Potential Impact upon Human Infection". BMC Vet. Res. 3: 9. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-3-9. PMC 1885244. PMID 17493260.

- ↑ Li TC, Chijiwa K, Sera N, et al. (2005). "Hepatitis E Virus Transmission from Wild Boar Meat". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (12): 1958–60. doi:10.3201/eid1112.051041. PMC 3367655. PMID 16485490.

- ↑ Kuniholm MH & Nelson KE (2008). "Of Organ Meats and Hepatitis E Virus: One Part of a Larger Puzzle Is Solved". J Infect Dis. 198 (12): 1727–1728. doi:10.1086/593212. PMID 18983247.

- ↑ Johne R, Plenge-Bönig A, Hess M, Ulrich RG, Reetz J, Schielke A; Plenge-Bönig; Hess; Ulrich; Reetz; Schielke (March 2010). "Detection of a novel hepatitis E-like virus in faeces of wild rats using a nested broad-spectrum RT-PCR". J. Gen. Virol. 91 (Pt 3): 750–8. doi:10.1099/vir.0.016584-0. PMID 19889929.

- ↑ Cheng X, Wang S, Dai X, Shi C, Wen Y, Zhu M, Zhan S, Meng J; Wang; Dai; Shi; Wen; Zhu; Zhan; Meng (2012). "Rabbit as a novel animal model for hepatitis e virus infection and vaccine evaluation". PLoS ONE. 7 (12): e51616. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751616C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051616. PMC 3521758. PMID 23272124.

- ↑ Birke L, Cormier SA, You D, Stout RW, Clement, Johnson M, et al. Hepatitis E antibodies in laboratory rabbits from 2 US vendors. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Apr [April 3, 2014]. doi:10.3201/eid2004.131229

- ↑ Morrow, Chris J.; Samu, Győző; Mátrai, Eszter; Klausz, Ákos; Wood, Alasdair M.; Richter, Susanne; Jaskulska, Barbara; Hess, Michael (2008-10-01). "Avian hepatitis E virus infection and possible associated clinical disease in broiler breeder flocks in Hungary". Avian Pathology. 37 (5): 527–535. doi:10.1080/03079450802356946. ISSN 0307-9457. PMID 18798029.

- 1 2 Cao, Dianjun; Meng, Xiang-Jin (2012-08-22). "Molecular biology and replication of hepatitis E virus". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 1 (8): e17. doi:10.1038/emi.2012.7. PMC 3630916. PMID 26038426.

- ↑ Tao, TS; Liu, Z; Ye, Q; Mata, DA; Li, K; Yin, C; Zhang, J; Tao, YJ (Aug 4, 2009). "Structure of the hepatitis E virus-like particle suggests mechanisms for virus assembly and receptor binding". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (31): 12992–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10612992G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904848106. PMC 2722310. PMID 19622744.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Purdy MA, Khudyakov YE; Khudyakov (2010). Tavis, John E, ed. "Evolutionary history and population dynamics of hepatitis E virus". PLoS ONE. 5 (12): e14376. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514376P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014376. PMC 3006657. PMID 21203540.

- ↑ "Hepatitis E Questions and Answers for Health Professionals | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Aggarwal, Rakesh (2 October 2012). "Diagnosis of hepatitis E". Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 10 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.187. ISSN 1759-5045. Retrieved 29 September 2018. subscription needed

- ↑ Shrestha MP, Scott RM, Joshi DM, et al. (2007). "Safety and efficacy of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (9): 895–903. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061847. PMID 17329696.

- 1 2 Park, S. B. (November 2012). "Hepatitis E vaccine debuts". Nature. 491 (7422): 21–22. Bibcode:2012Natur.491...21P. doi:10.1038/491021a. PMID 23128204.

- ↑ "HEV FAQs for Health Professionals | Division of Viral Hepatitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Labrique, Alain B.; Sikder, Shegufta S.; Krain, Lisa J.; West, Keith P.; Christian, Parul; Rashid, Mahbubur; Nelson, Kenrad E. (2012-09-01). "Hepatitis E, a Vaccine-Preventable Cause of Maternal Deaths". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (9): 1401–1404. doi:10.3201/eid1809.120241. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3437697. PMID 22931753.

- 1 2 "Hepatitis E vaccine: WHO position paper, May 2015" (PDF). Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire. 90 (18): 185–200. 1 May 2015. PMID 25935931.

- ↑ "Hepatitis E Treatment & Management: Medical Management, Diet and Activity".

- ↑ Kamar, Nassim; Izopet, Jacques; Tripon, Simona; Bismuth, Michael; Hillaire, Sophie; Dumortier, Jérôme; Radenne, Sylvie; Coilly, Audrey; Garrigue, Valérie (2014-03-20). "Ribavirin for Chronic Hepatitis E Virus Infection in Transplant Recipients". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (12): 1111–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215246. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 24645943.

- ↑ Lozano, Rafael (2010). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010" (PDF). The Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Navaneethan, Udayakumar; Mohajer, Mayar Al; Shata, Mohamed T (2008-11-01). "Hepatitis E and Pregnancy- Understanding the pathogenesis". Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 28 (9): 1190–1199. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01840.x. ISSN 1478-3223. PMC 2575020. PMID 18662274.

- ↑ Lewis, Hannah C.; Boisson, Sophie; Ijaz, Samreen; Hewitt, Kirsten; Ngui, Siew Lin; Boxall, Elizabeth; Teo, Chong Gee; Morgan, Dilys (2008-01-01). "Hepatitis E in England and Wales". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (1): 165–167. doi:10.3201/eid1401.070307. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2600160. PMID 18258100.

- ↑ "WHO | Hepatitis E in Chad". www.who.int. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ↑ "WHO | Hepatitis E in Sudan". www.who.int. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ↑ Teshale EH, Howard CM, Grytdal SP, et al. (January 2010). "Hepatitis E epidemic, Uganda". Emerging Infect. Dis. 16 (1): 126–9. doi:10.3201/eid1601.090764. PMC 2874362. PMID 20031058.

- ↑ Nurul Islam Hasib (June 14, 2011). "Hepatitis E sounds alarm". bdnews24.com. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Investigation of Hepatitis E Outbreak Among Refugees — Upper Nile, South Sudan, 2012-2013". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ↑ Hereward Holland (February 2, 2013). "Hepatitis outbreak kills 88 in South Sudan—aid agency". Reuters. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Nine killed, 6000 fall ill due to Hepatitis E in Morang". Republica. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Hepatitis E cases in Namibia rise to 490 - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. January 28, 2018.

- ↑ Mirazo S, Mir D, Bello G, Ramos N, Musto H, Arbiza J (2016). "New insights into the hepatitis E virus genotype 3 phylodynamics and evolutionary history". Infect Genet Evol. 43: 267–73. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2016.06.003. PMID 27264728.

Further reading

- Riveiro-Barciela, M (2013). "Hepatitis E virus: new faces of an old infection" (PDF). Annals of Hepatology. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Parvez, Mohammad Khalid (2013-01-01). "Chronic hepatitis E infection: risks and controls". Intervirology. 56 (4): 213–216. doi:10.1159/000349888. ISSN 1423-0100. PMID 23689166.

- Aggarwa, Rakesh; Gandhi, Sanjay (December 2010). "A systematic review on prevalence of hepatitis E disease and seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus antibody" (PDF). World Health Organization. WHO/IVB/10.14.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hepatitis E virus. |

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Hepeviridae

- Bjorn, Genevive (18 October 2010). "The night my liver started running my life". New York Times.