Capsid

.gif)

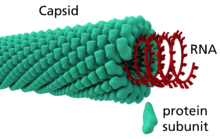

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus. It consists of several oligomeric structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may not correspond to individual proteins, are called capsomeres. The capsid encloses the genetic material of the virus.

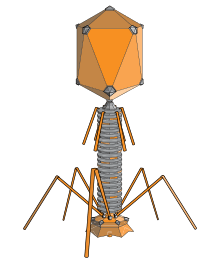

Capsids are broadly classified according to their structure. The majority of viruses have capsids with either helical or icosahedral[2][3] structure. Some viruses, such as bacteriophages, have developed more complicated structures due to constraints of elasticity and electrostatics.[4] The icosahedral shape, which has 20 equilateral triangular faces, approximates a sphere, while the helical shape resembles the shape of a spring, taking the space of a cylinder but not being a cylinder itself.[5] The capsid faces may consist of one or more proteins. For example, the foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid has faces consisting of three proteins named VP1–3.[6]

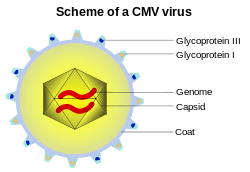

Some viruses are enveloped, meaning that the capsid is coated with a lipid membrane known as the viral envelope. The envelope is acquired by the capsid from an intracellular membrane in the virus' host; examples include the inner nuclear membrane, the golgi membrane, and the cell's outer membrane.[7]

Once the virus has infected a cell and begins replicating itself, new capsid subunits are synthesized according to the genetic material of the virus, using the protein biosynthesis mechanism of the cell. During the assembly process, a portal subunit is assembled at one vertex of the capsid. Through this portal, viral DNA or RNA is transported into the capsid.[8]

Structural analyses of major capsid protein (MCP) architectures have been used to categorise viruses into families. For example, the bacteriophage PRD1, Paramecium bursaria Chlorella algal virus, and mammalian adenovirus have been placed in the same family.[9][10]

Specific shapes

Icosahedral

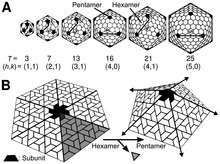

The icosahedral structure is extremely common among viruses. The number and arrangement of capsomeres in an icosahedral capsid can be classified using the "quasi-equivalence principle" proposed by Donald Caspar and Aaron Klug.[11] Like the Goldberg polyhedra, an icosahedral structure can be regarded as being constructed from pentamers and hexamers. The structures can be indexed by two integers h and k, with and ; the structure can be thought of as taking h steps from the edge of a pentamer, turning 60 degrees counterclockwise, then taking k steps to get to the next pentamer. The triangulation number T for the capsid is defined as:

Icosahedral capsids contain 12 pentamers plus 10(T − 1) hexamers. [12][13] The T-number is representative of the size and complexity of the capsid proteins: all know viruses with T > 7 require auxiliary proteins for assembly.[14] Geometric examples for many values of h, k, and T can be found at List of geodesic polyhedra and Goldberg polyhedra. Although this classification can be applied to the majority of known viruses, exceptions are known including the retroviruses where point mutations disrupt the symmetry.[13]

T-numbers can be represented in different ways, for example T = 1 can only be represented as an icosahedron or a dodecahedron and, depending on the type of quasi-symmetry, T = 3 can be presented as a truncated dodecahedron, an icosidodecahedron, or a truncated icosahedron and their respective duals a triakis icosahedron, a rhombic triacontahedron, or a pentakis dodecahedron.[15]

Prolate

An elongated icosahedron is a common shape for the heads of bacteriophages. Such a structure is composed of a cylinder with a cap at either end. The cylinder is composed of 10 triangles. The Q number, which can be any positive integer, specifies the number of triangles, composed of asymmetric subunits, that make up the 10 triangles of the cylinder. The caps are classified by the T number.[16]

Helical

Many rod-shaped and filamentous plant viruses have capsids with helical symmetry.[17] The helical structure can be described as a set of n 1-D molecular helices related by an n-fold axial symmetry.[18] The helical transformation are classified into two categories: one-dimensional and two-dimensional helical systems.[18] Creating an entire helical structure relies on a set of translational and rotational matrices which are coded in the protein data bank.[18] Helical symmetry is given by the formula P = μ x ρ, where μ is the number of structural units per turn of the helix, ρ is the axial rise per unit and P is the pitch of the helix. The structure is said to be open due to the characteristic that any volume can be enclosed by varying the length of the helix.[19] The most understood helical virus is the tobacco mosaic virus.[17] The virus is a single molecule of (+) strand RNA. Each coat protein on the interior of the helix bind three nucleotides of the RNA genome. Influenza A viruses differ by comprising multiple ribonucleoproteins, the viral NP protein organizes the RNA into a helical structure. The size is also different the tobacco mosaic virus has a 16.33 protein subunits per helical turn,[17] while the influenza A virus has a 28 amino acid tail loop.

Functions

The functions of the virion are to:

- protect the genome,

- deliver the genome, and

- interact with the host.

The virion must assemble a stable, protective protein shell to protect the genome from lethal chemical and physical agents. These include forms of natural radiation, extremes of pH or temperature and proteolytic and nucleolytic enzymes. Delivery of the genome is also important by specific binding to external receptors of the host cell, transmission of specific signals that induce uncoating of the genome, and induction of fusion with host cell membranes.[19]

Chemical properties

The viral particle must be metastable so that interactions can be readily reversed when entering and uncoating a new host cell. If it attains the minimum free energy state, in which its system is in a state of equilibrium, it will be unlikely - and energetically unfavorable - for the subunits of the capsid to reverse their molecular interactions that are associated with attachment and entry into the host cell.[20] Each subunit of the capsid has identical bonding contacts with its neighbors, and the two binding contacts are usually noncovalent. The non-covalent bonding holds the structural unit together. The reversible formation of non-covalent bonds between properly folded subunits leads to error-free assembly and minimizes free energy, while maintaining metastability.[19]

Origin and evolution

It has been suggested that many viral capsid proteins have evolved on multiple occasions from functionally diverse cellular proteins.[21] The recruitment of cellular proteins appears to have occurred at different stages of evolution, so that some cellular proteins were captured and refunctionalized prior to the divergence of cellular organisms into the three contemporary domains of life, whereas others were hijacked relatively recently. As a result, some capsid proteins are widespread in viruses infecting distantly related organisms (e.g., capsid proteins with the jelly-roll fold), whereas others are restricted to a particular group of viruses (e.g., capsid proteins of alphaviruses).[21]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capsid. |

- ↑ Asensio MA, Morella NM, Jakobson CM, Hartman EC, Glasgow JE, Sankaran B, Zwart PH, Tullman-Ercek D. "A Selection for Assembly Reveals That a Single Amino Acid Mutant of the Bacteriophage MS2 Coat Protein Forms a Smaller Virus-like Particle". Nano Lett.

- ↑ Lidmar J, Mirny L, Nelson DR (2003). "Virus shapes and buckling transitions in spherical shells". Phys. Rev. E. 68 (5): 051910. arXiv:cond-mat/0306741. Bibcode:2003PhRvE..68e1910L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.68.051910.

- ↑ Vernizzi G, Olvera de la Cruz M (2007). "Faceting ionic shells into icosahedra via electrostatics". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104 (47): 18382–18386. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10418382V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703431104. PMC 2141786.

- ↑ Vernizzi G, Sknepnek R, Olvera de la Cruz M (2011). "Platonic and Archimedean geometries in multicomponent elastic membranes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108 (11): 4292–4296. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.4292V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012872108. PMC 3060260. PMID 21368184.

- ↑ Branden, Carl; Tooze, John (1991). Introduction to Protein Structure. New York: Garland. pp. 161–162. ISBN 0-8153-0270-3.

- ↑ "Virus Structure (web-books.com)".

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce; Bray, Dennis; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Watson, James D. (1994). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). p. 280.

- ↑ Newcomb WW, Homa FL, Brown JC (August 2005). "Involvement of the Portal at an Early Step in Herpes Simplex Virus Capsid Assembly". Journal of Virology. 79 (16): 10540–6. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.16.10540-10546.2005. PMC 1182615. PMID 16051846.

- ↑ Krupovic, M; Bamford, DH (2008). "Virus evolution: how far does the double beta-barrel viral lineage extend?". Nat Rev Microbiol. 6 (12): 941–8. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2033. PMID 19008892.

- ↑ Khayat et al. classified Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus (STIV) and Laurinmäki et al. classified bacteriophage Bam35 – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3669 (2006); 102, 18944 (2005); Structure 13, 1819 (2005)

- ↑ Caspar, D. L. D.; Klug, A. (1962). "Physical Principles in the Construction of Regular Viruses". Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 27: 1–24. doi:10.1101/sqb.1962.027.001.005. PMID 14019094.

- ↑ "T-number index". VIPERdb. La Jolla, CA: The Scripps Research Institute. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn840. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- 1 2 Johnson, J. E.; Speir, J.A. (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 115–123. ISBN 0-12-375146-2.

- ↑ Mannige RV, Brooks CL III (2010). "Periodic Table of Virus Capsids: Implications for Natural Selection and Design". PLoS ONE. 5 (3): e9423. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9423M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009423. PMC 2831995. PMID 20209096.

- ↑ K. V. Damodaran; Vijay S. Reddy; John E. Johnson; Charles L. Brooks III (2002). "A General Method to Quantify Quasi-equivalence in Icosahedral Viruses". J. Mol. Biol. 324 (4): 723–737. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01138-5. PMID 12460573.

- ↑ Casens, S. (2009). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 167–174. ISBN 0-12-375146-2.

- 1 2 3 Yamada S, Matsuzawa T, Yamada K, Yoshioka S, Ono S, Hishinuma T (December 1986). "Modified inversion recovery method for nuclear magnetic resonance imaging". Sci Rep Res Inst Tohoku Univ Med. 33 (1–4): 9–15. PMID 3629216.

- 1 2 3 Aldrich RA (February 1987). "Children in cities—Seattle's KidsPlace program". Acta Paediatr Jpn. 29 (1): 84–90. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200x.1987.tb00013.x. PMID 3144854.

- 1 2 3 Racaniello, Vincent R.; Enquist, L. W. (2008). Principles of Virology, Vol. 1: Molecular Biology. Washington, D.C: ASM Press. ISBN 1-55581-479-4.

- ↑ http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/~cchieh/cact/applychem/gibbsenergy.html

- 1 2 Krupovic, M; Koonin, EV (2017). "Multiple origins of viral capsid proteins from cellular ancestors". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 114 (12): E2401–E2410. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621061114. PMC 5373398. PMID 28265094.

- Robert Williams The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A source book of Design, 1979, pp. 142–144, Figure 4-49,50,51 Custers of 12 spheres, 42 spheres, 92 spheres

- Antony Pugh, Polyhedra: a visual approach, 1976, Chapter 6. The Geodesic Polyhedra of R. Buckminster Fuller and Related Polyhedra