Viral life cycle

|

Viruses are only able to replicate themselves by commandeering the reproductive apparatus of cells and making them reproduce the virus's genetic structure instead. Thus, a virus cannot function or reproduce outside a cell, thereby being totally dependent on a host cell in order to survive.[1] Most viruses are species specific, and related viruses typically only infect a narrow range of plants, animals, bacteria, or fungi.

Life cycle process

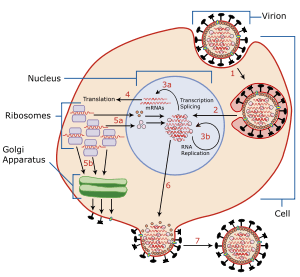

Viral entry

For the virus to reproduce and thereby establish infection, it must enter cells of the host organism and use those cells' materials. To enter the cells, proteins on the surface of the virus interact with proteins of the cell. Attachment, or adsorption, occurs between the viral particle and the host cell membrane. A hole forms in the cell membrane, then the virus particle or its genetic contents are released into the host cell, where replication of the viral genome may commence.

Viral replication

Next, a virus must take control of the host cell's replication mechanisms. It is at this stage a distinction between susceptibility and permissibility of a host cell is made. Permissibility determines the outcome of the infection. After control is established and the environment is set for the virus to begin making copies of itself, replication occurs quickly by the millions.

Viral shedding

After a virus has made many copies of itself, it has usually exhausted the cell of its resources. The host cell is now no longer useful to the virus, therefore the cell often dies and the newly produced viruses must find a new host. The process by which virus progeny are released to find new hosts, is called shedding. This is the final stage in the viral life cycle.

Viral latency

Some viruses can "hide" within a cell, either to evade the host cell defenses or immune system, or simply because it is not in the best interest of the virus to continually replicate. This hiding is deemed latency. During this time, the virus does not produce any progeny, it remains inactive until external stimuli—such as light or stress—prompts it to activate.

References

- ↑ N.J. Dimmock et al. "Introduction to Modern Virology, 6th edition." Blackwell Publishing, 2007.