Cyclosporiasis

| Cyclosporiasis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | A07.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 007.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 32228 |

| eMedicine | [1]/topic527.htm ped [1]/527 |

| Patient UK | Cyclosporiasis |

| MeSH | D021866 |

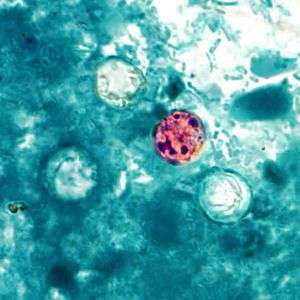

Cyclosporiasis is a disease caused by infection with Cyclospora cayetanensis, a pathogenic protozoan transmitted by feces or feces-contaminated food and water.[2] Outbreaks have been reported due to contaminated fruits and vegetables. It is not spread from person to person, but can be a hazard for travelers as a cause of diarrhea.

Mode of infection

Cyclosporiasis primarily affects humans and other primates. When an oocyst of Cyclospora cayetanensis enters the small intestine, it invades the mucosa, where it incubates for about one week. After incubation, the infected person begins to experience severe watery diarrhea, bloating, fever, stomach cramps, and muscle aches.

The parasite particularly affects the jejunum of the small intestine. Of nine patients in Nepal who were diagnosed with cyclosporiasis, all had inflammation of the lamina propria along with an increase of plasma in the lamina propria. Oocysts were also observed in duodenal aspirates.[3]

Oocysts are often present in the environment as a result of using contaminated water or human feces as fertilizer.

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis can be difficult due to the lack of recognizable oocysts in the feces. PCR-based DNA tests and acid-fast staining can help with identification. The infection is often treated with trimethaprim-sulfamethaxozol, also known as Bactrim or co-trimoxazole, because traditional anti-protozoal drugs are not sufficient. To prevent transmission, food should be cooked thoroughly and drinking water from streams should be avoided.

Vaccine research

There is no vaccine to prevent cyclosporiasis in humans at present, but one is available for reduction of fetal losses in sheep.

Epidemiology

The first recorded cases of cyclosporiasis in humans were as recent as 1977, 1978, and 1979. They were reported by Ashford, a British parasitologist who discovered three cases while working in Papua New Guinea. Ashford found that the parasite had very late sporulation, from 8–11 days, making the illness difficult to diagnose. When examining feces, the unsporulated oocysts can easily be mistaken for fungal spores, and thus can be easily overlooked.[4]

In 2007, Indian researchers published a case report that found an association between Cyclospora infection and Bell's palsy. This was the first reported case of Bell’s palsy following chronic Cyclospora infection.[5] In addition to other extra-intestinal reports, cyclosporiasis might be involved in either reversible neuronal damage or other unknown mechanisms to lead to Guillain-Barré syndrome or Bell's palsy.

In 2010, a report of Cyclospora transmission via swimming in the Kathmandu Valley was published in the Journal of Institute of Medicine.[6] The researchers found that openly defecated human stool samples around the swimmer's living quarters and near the swimming pool were positive for Cyclospora. However, they did not find the parasite in dog stool, bird stool, cattle dung, vegetable samples, or water samples. They concluded that pool water contaminated via environmental pollution might have caused the infection, as the parasite can resist chlorination in water.[7]

Cyclosporiasis infections have been well reported in Nepal. In one study, Tirth Raj Ghimire, Purna Nath Mishra, and Jeevan Bahadur Sherchan collected samples of vegetables, sewage, and water from ponds, rivers, wells, and municipal taps in the Kathmandu Valley from 2002 to 2004.[8] They found Cyclospora in radish, cauliflower, cabbage, and mustard leaves, as well as sewage and river water. This first epidemiological study determined the seasonal character of cyclosporiasis outbreaks in Nepal during the rainy season, from May to September.[9]

Cyclosporiasis in AIDS patients

At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, cyclosporiasis was identified as one of the most important opportunistic infections among AIDS patients.[1]

In 2005, Ghimire and Mishra reported a case of cyclosporiasis in a patient with low hemoglobin and suggested that this coccidian might be involved in reducing hemoglobin due to lack of immune system [10]. In 2006, their groups published a paper about the role of cyclosporiasis in HIV/AIDS patients and non-HIV/AIDS patients in the Kathmandu Valley.[11]

In 2008, Indian researchers published a report about the epidemiology of Cyclospora in HIV/AIDS patients in Kathmandu.[12] They examined samples of soil, river water, sewage, chicken stool, dog stool, and stool in the streets, and found them positive for Cyclospora. They also evaluated several risk factors for cyclosporiasis in AIDS patients.[13]

Outbreaks

Although it was initially thought that Cyclospora was confined to tropical and subtropical regions, occurrences of cyclosporiasis are becoming more frequent in North America. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been 11 documented cyclosporiasis outbreaks in the U.S. and Canada since the 1990s. The CDC also recorded 1,110 laboratory-confirmed sporadic instances of cyclosporiasis.[14]

Between June and August 2013, multiple independent outbreaks of the disease in the U.S. sickened at least 631 people across 25 states.[15][16] Investigations later identified a bagged salad mixture as the cause of an outbreak in Iowa and Nebraska.[17]

In 2015, the CDC was notified of 546 persons with confirmed cyclosporiasis infection across 31 states. Cluster investigations in Texas, where the greatest number of infections was reported, indicated that contaminated cilantro was the culprit.[18]

During July 21–August 8, 2017, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) was notified of 20 cases of cyclosporiasis among persons who dined at a Mediterranean-style restaurant chain (chain A) in the Houston area.[19]

On July 31, 2018, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) issued a public health alert for certain beef, pork and poultry salad and wrap products potentially contaminated with Cyclospora.[20] The contamination came from the chopped romaine lettuce used in these products.

References

- 1 2 3 Ortega, Ynes. "Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a Food-Borne and Waterborne Parasite". American Society for microbiology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ↑ Talaro, Kathleen P., and Arthur Talaro. Foundations in Microbiology: Basic Principles. Dubuque, Iowa: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

- ↑ http://cmr.asm.org/content/23/1/218.full

- ↑ Strausbaugh, Larry (1 October 2000). "Cyclospora cayetanensis: A Review, Focusing on the Outbreaks of Cyclosporiasis in the 1990s". Infectious Disease Society of America. 31 (4): 1040. doi:10.1086/314051. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN, Sherchand JB, Ghimire LV: Bell’s Palsy and Cyclosporiasis: Causal or Coincidence? Nepal Journal of Neuroscience 4:86- 88, 2007. http://neuroscience.org.np/neuro/issues/uploads/abstract_K3M0aH6IUP.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JIOM/article/download/4003/3392

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Ghimire LV, Shahu RK, Mishra PN. Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora infection transmission by swimming. Journal of Institute of Medicine. 2010; 32 (1): 43–45.https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JIOM/article/download/4003/3392

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN, Sherchand JB. The seasonal outbreaks of Cyclospora and Cryptosporidium in Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2005; 3(1): 39–48.http://jnhrc.com.np/index.php/jnhrc/article/view/99/96

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN, Sherchand JB. The seasonal outbreaks of Cyclospora and Cryptosporidium in Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2005; 3(1): 39–48. http://jnhrc.com.np/index.php/jnhrc/article/view/99/96

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN. Intestinal parasites and Haemoglobin concentration in the people of two different areas of Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2005; 3(2): 1–7.http://jnhrc.com.np/index.php/jnhrc/article/view/103/100

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN. Intestinal parasites in the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infected Patients in Kathmandu, Nepal. The Nepalese Journal of Zoology. 2006; 1(1): 9–19.

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN, Sherchan JB. Epidemiology of Cyclospora cayetanensis and other intestinal parasites in the HIV infected patients in Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2008; 6(12): 28–37.https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JNHRC/article/download/2441/2177

- ↑ Ghimire TR, Mishra PN, Sherchan JB. Epidemiology of Cyclospora cayetanensis and other intestinal parasites in the HIV infected patients in Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2008; 6(12): 28–37.https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JNHRC/article/download/2441/2177

- ↑ "Surveillance for Laboratory-Confirmed Sporadic Cases of Cyclosporiasis --- United States, 1997--2008". cdc.gov.

- ↑ "Case Count Maps - Outbreak Investigations 2013 - Cyclosporiasis - CDC". cdc.gov.

- ↑ "CDC: 425 cases of cyclospora infection identified across 16 states". cbsnews.com. 5 August 2013.

- ↑ http://www.idph.state.ia.us/IDPHChannelsService/file.ashx?file=2721EA4A-DB6B-4746-9FF4-0BF09C9BF3BE Iowa Cyclospora Outbreak 2013 /Outbreak Update 7.31.13, Iowa State Department of Public Health. Downloaded 6 Aug 2013.

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2015/index.html

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6721a5.htm

- ↑ "FSIS Issues Public Health Alert for Beef, Pork and Poultry Salad and Wrap Products due to Concerns about Contamination with Cyclospora". usda.gov. 31 July 2018.

External links

- Cyclosporiasis at Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

- Cyclospora Infection at MayoClinic.com