Halley Research Station

| Halley Research Station | |

|---|---|

Halley VI Station | |

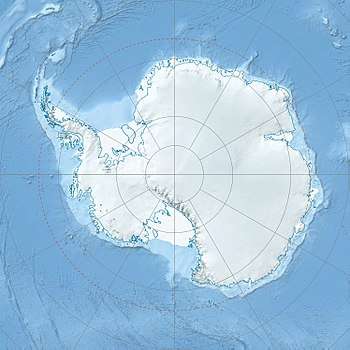

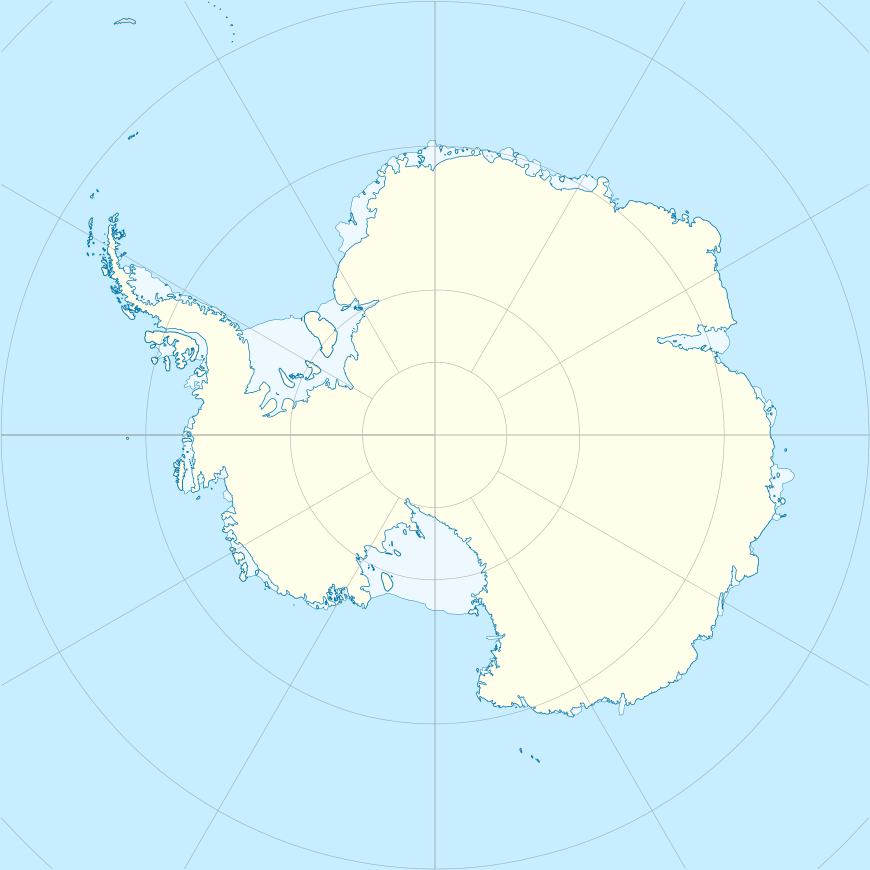

Location of Halley within Antarctica | |

| General information | |

| Type | Modular |

| Location |

Brunt Ice Shelf Caird Coast Antarctica |

| Coordinates | 75°36′45″S 26°11′52″W / 75.612543°S 26.197797°WCoordinates: 75°36′45″S 26°11′52″W / 75.612543°S 26.197797°W |

| Elevation | 30 metres (98 ft) |

| Named for | Edmond Halley |

| Construction started | 15 January 1956 (Halley I) |

| Opened | 5 February 2013 (Halley VI) |

| Owner |

British Antarctic Survey (BAS) Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 2,000 m2 (22,000 sq ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Hugh Broughton Architects |

| Developer | British Antarctic Survey (BAS) |

| Engineer | AECOM |

| Main contractor | Galliford Try |

| Website | |

| Halley VI @ bas.ac.uk | |

| Halley Research Station | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Private | ||||||||||

| Location |

Halley Research Station Brunt Ice Shelf | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 75°35′00″S 26°39′36″W / 75.583332°S 26.659999°W | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

Halley Research Station Location of airfield in Antarctica | |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Halley Research Stations | |

|---|---|

| Halley I | 1956–1967 |

| Halley II | 1967–1973 |

| Halley III | 1973–1983 |

| Halley IV | 1983–1991 |

| Halley V | 1990–2011 |

| Halley VI | 2012–present |

.jpg)

Halley Research Station, run by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), is a scientific research station on the Brunt Ice Shelf floating on the Weddell Sea in Antarctica. As with the German Neumayer-Station III it is built on an ice shelf floating on the sea, versus being on solid land on the continent of Antarctica. Because the ice shelf is slowly moving towards the open ocean it will eventually calve off creating a drifting iceberg.[2][3]

In 2002, the BAS realized there was a calving event that would destroy Halley V, so a competition was undertaken to design a replacement station. The current base structure, the Halley VI, is notable for being the world's first fully relocatable terrestrial research station, and is distinguishable by its colourful modular structure that is built upon huge hydraulic skis.[4]

It is a British research facility[5] dedicated to the study of the Earth's atmosphere. Measurements from Halley led to the discovery of the ozone hole in 1985.[6]

History

Halley was founded in 1956, for the International Geophysical Year of 1957–1958, by an expedition from the Royal Society. The bay where the expedition decided to set up their base was named Halley Bay, after the astronomer Edmond Halley. The name was changed to Halley in 1977 as the original bay had disappeared due to changes in the ice shelf. The latest station, Halley VI, was officially opened in February 2013 after a test winter.[7]

On 30 July 2014, the station lost its electrical and heating supply for 19 hours.[8] During the power cut, there were record low temperatures. Power was partially restored, but all science activities, apart from meteorological observations essential for weather forecasting, were suspended.[9] Plans were made to vacate some of the eight modules and to shelter in the remaining few that still had heat.[10]

The buildings

There have been five previous bases at Halley. Various construction methods have been tried, from unprotected wooden huts to steel tunnels. The first four were all buried by snow accumulation and crushed until they were uninhabitable.[11]

Halley I

Halley II

Halley III

- Built: 1973

- Abandoned: 1983

- Structure: Built inside Armco steel tubing designed to take the snow loadings building up over it

Halley IV

- Built: 1983

- Abandoned: 1994, engulfed and abandoned

- Structure:

- Two-storey buildings constructed inside four interconnected plywood tubes with access shafts to the surface. The tubes were 9 metres in diameter and consisted of insulated reinforced panels designed to withstand the pressures of being buried in snow and ice.[19][20]

- Designed to cope with being buried in snow.

Halley V

- Built: completed 1990, operational 1989

- Demolished: late 2012

- Once its successor, Halley VI, was operational, Halley V was demolished[21]

- Structure:

- Main buildings were built on steel platforms that were raised annually to keep them above the snow surface.

- Stilts were fixed on the flowing ice shelf so it eventually got too close to the calving edge.[6]

- Lawes platform: Main platform

- Drewry summer accommodation: 2-storey building was on skis and could be dragged to a new higher location each year.[22]

- The Drewry block was later moved to join the Halley VI base

- Simpson Building (Ice and Climate Building) (ICB): On stilts[23] and was raised each year to counteract the buildup of snow

- It housed the Dobson spectrophotometer used to discover the ozone hole.

- Piggott platform (Space Science Building): Used for upper atmosphere research.[24]

Halley VI

- Built: Over four summers, first operational data 28 February 2012, officially opened 2013.[25][26]

- Structure: Modular

- Cost: Approximately £26 million[2]

Halley VI is a string of eight modules which, like Halley V, are jacked up on hydraulic legs to keep it above the accumulation of snow. Unlike Halley V, there are retractable giant skis on the bottom of these legs, which allow the building to be relocated periodically.[27][28][29][30][31]

The Drewry summer accommodation building and the garage from Halley V were dragged to the Halley VI location and continue to be used. The Workshop and Storage Platform (WASP) provides storage for field equipment and a workshop for technical services. There are six external science cabooses which house scientific equipment for each experiment spread across the site and the Clean Air Sector Laboratory (CASLab) 1km from the station.

Design competition

An architectural design competition was launched by RIBA Competitions and the British Antarctic Survey in June 2004 to provide a new design for Halley VI. The competition was entered by a number of architectural and engineering firms. The winning design, by Faber Maunsell and Hugh Broughton Architects was chosen in July 2005.[2][4]

Halley VI was built in Cape Town, South Africa by a South African consortium.[32][33] 26 modular accommodation pods were added in total, installed in eight modules,[34] which provides fully serviced accommodation for 32 people. The first sections were shipped to Antarctica in December 2007. It was assembled next to Halley V,[35] then dragged one-by-one 15 km and reconnected.[36]

Halley VI Station was officially opened in Antarctica on 5 February 2013. Kirk Watson, a filmmaker from Scotland, recorded the building of the station over a 4-year period for a short film. A description of the engineering challenges and the creation of the consortium was provided by Adam Rutherford to coincide with an exhibition in Glasgow.[37]

Design elements

A focus of the new architecture was the desire to improve the living conditions of the scientists and staff on the station. Solutions included consulting a colour psychologist to create a special colour palette to offset the more than 100 days of darkness each year, daylight simulation lamp alarm clocks to address biorhythm issues, the use of special wood veneers to imbue the scent of nature and address the lack of green growth, as well as lighting design and space planning to address social interaction needs and issues of living and working in isolation.[2][4]

Another priority of the structure construction was to have the least environmental impact on the ice as possible.[2]

Relocation

The British Antarctic Survey announced that it intended to move Halley VI to a new site in summer 2016-2017.[38] A large crack had been propagating through the ice and threatened to cut the station off from the main body of the ice shelf, prompting the decision to move. The planned move would see the station shifted 23 kilometres (14 mi) from its previous site and would be the first time the station had been moved since it became operational in 2012.

Whilst the station was being relocated, concerns about a new crack which had been discovered on 31 October 2016 (dubbed the "Halloween Crack") led the BAS to announce that they would withdraw their staff from the base in March 2017.[39] BAS completed the relocation of the base in February 2017.[40] Staff returned after the Antarctic winter, in November 2017 and found the station in very good shape.[41] The station was not manned in winter 2018.[42] Horizon, the long-running BBC documentary series, sent film-maker Natalie Hewit to Antarctica for three months to document the move.[43]

Environment

Temperatures at Halley rarely rise above 0 °C although temperatures around -10 °C are common on sunny summer days. Typical winter temperatures are below -20 °C with extreme lows of around -55 °C.[6]

| Climate data for Halley Research Station (extremes 1956–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.2 (45) |

5.3 (41.5) |

1.1 (34) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

0.0 (32) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−1.1 (30) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

2.2 (36) |

6.8 (44.2) |

7.2 (45) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−19.3 (−2.7) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−25.2 (−13.4) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−8.9 (16) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−29.2 (−20.6) |

−28.2 (−18.8) |

−26.2 (−15.2) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−18.5 (−1.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−19.3 (−2.7) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−29.0 (−20.2) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

−31.5 (−24.7) |

−30.0 (−22) |

−23.6 (−10.5) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.9 (−9.2) |

−31.8 (−25.2) |

−41.0 (−41.8) |

−50.9 (−59.6) |

−54.2 (−65.6) |

−54.0 (−65.2) |

−54.4 (−65.9) |

−53.0 (−63.4) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−44.1 (−47.4) |

−32.0 (−25.6) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−54.4 (−65.9) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 77 | 77 | 70 | 72 | 72 | 76 | 80 | 82 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 251.1 | 194.9 | 117.8 | 45.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 24.8 | 87.0 | 204.6 | 255.0 | 244.9 | 1,425.1 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.1 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 8.5 | 7.9 | 3.9 |

| Source #1: Deutscher Wetterdienst[44] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[45] | |||||||||||||

Winds are predominantly from the east; strong winds often picking up the dusty surface snow reducing visibility to a few metres.

One of the reasons for the location of Halley is that it is under the auroral oval, making it ideally located for geospace research and resulting in frequent displays of the Aurora Australis overhead. These are easiest to see during the 105 days (29 Apr - 13 Aug) when the Sun does not rise above the horizon.

Inhabitants

During the winter months there are usually around 13 overwintering staff. In a typical winter the team is isolated from when the last aircraft leaves in early March until the first plane arrives in late October. In the peak summer period, from late December to late February, staff numbers increase to around 70.

Sometimes, none of the wintering team are scientists. Most are the technical specialists required to keep the station and the scientific experiments running. The 2016 wintering team at Halley included a chef, a doctor, a communications manager, a vehicle mechanic, a generator mechanic, an electrician, a plumber, a field assistant, two electronics engineers, a meteorologist and a data manager. In addition there is a Winter Station Leader who is sworn in as a magistrate prior to deployment. Their main role is to oversee the day-to-day management of the station.

1996 saw the first female winterers at Halley. Since 2009 there are usually at least two women that winter each year.[46]

Base life

Life in Antarctica is dominated by the seasons, with a short, hectic summer and a long winter. In bases such as Halley that are resupplied by sea, the most significant event of the year is the arrival of the resupply ship (currently the RRS Ernest Shackleton, before 1999 the RRS Bransfield) in late December. This is followed by intense activity to unload all supplies before the ship has to leave again; typically, this is done in less than two weeks.

The Halley summer season runs from as early as mid-October when the first plane lands, until early March when the ship has left and the last aircraft leaves transiting through Halley and on to Rothera Research Station before heading to South America.

Significant dates in the winter are sundown (last day when the Sun can be seen) on April 29th, midwinter on June 21st and sunrise (first day when the Sun rises after winter) on August 13th. Traditionally, the oldest person on base lowers the tattered flag on sundown and the youngest raises a new one on sunrise. Midwinter is a week long holiday, during which a member of the wintering team is chosen to keep the old flag.

See also

References

- ↑ "Halley Research Station". Great Circle Mapper. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Piotrowski, Jan; Broughton, Hugh (13 March 2013). "Researching Antarctica: Resorting to skis" (Video). The Economist. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ Ferreira, Becky (23 February 2015). "This Antarctic Base Is More Remote Than the International Space Station". Motherboard. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 Piotrowski, Jan; Broughton, Hugh (13 March 2013). "Antarctic research: Resorting to skis". The Economist. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ "Who We Are". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- 1 2 3 "Halley Research Station". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ "12/13 Season – Official Launch & Demolition of Halley V". British Antarctic Survey. 8 January 2013. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Aston, Felicity (2015-01-19). "Halley VI: coming in from the cold".

- ↑ "Power-down at British Antarctic Survey Halley Research Station". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "British Antarctic Survey trapped without power during record cold -55.4° C". Committee For A Constructive Tomorrow. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Previous bases at Halley". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley Bay 1964-65". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley Bay 1964-65". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley Bay - 1957-1958". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley Bay 1957". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley II, Halley Bay Base Z, 1967-1973". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley II after its first winter". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Garage entrance to Halley III research station". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley IV 4 Antarctica historical building". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley IV tube construction". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley, Jan 2013". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Drewry building - summer accommodation". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Ice and Climate Building (ICB) Halley 5". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Piggott Platform at Halley. 2003-4". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley VI Research Station". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ "Halley VI - module designations". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Moore, Rowan (10 February 2013). "Halley VI research station, Antarctica – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ↑ "Halley VI from the air. 2010-11". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley VI - Red module on stilts". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley VI space frame newly fitted with its hydraulic legs and skis".

- ↑ "Halley VI from the air". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley VI". Petrel Engineering. Archived from the original on 2012-01-27. Retrieved 7 Jan 2011.

- ↑ "Halley VI". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 2010-12-23. Retrieved 7 Jan 2011.

- ↑ "Halley VI pods in module frames - 2010". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Aerial view of the construction line of Halley VI Research Station situated next to Halley V". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Halley VI, May 2011". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Sella, Andrea; Geim, Andre (25 July 2013). "2D supermaterials; Inside an MRI; Antarctic architecture". BBC Inside Science. 17 minutes in. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ "Halley Research Station relocation". British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ↑ Jonathan Amos (16 January 2017). "Ice crack to put UK Antarctic base in shut-down". BBC News. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Jonathan Amos (3 February 2017). "UK completes Antarctic Halley base relocation". BBC News. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "Halley VI Research Station ready for 2017 summer season". British Antarctic Survey. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "Halley Research Station will not winter in 2018". British Antarctic Survey. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "Antarctica - Ice Station Rescue". Horizon. BBC Two. June 7, 2017. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Halley Bay (Großbritannien) / Antarktis" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ "Station Halley" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ "Halley Bay - 2010". Z-Fids. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

Further reading

- Gough, Alex (2010). Solid Sea and Southern Skies Two Years in Antarctica. Dunedin, N.Z.: A. Gough. ISBN 978-0-473-18309-7. OCLC 702361699.

- Howe, A. Scott; Sherwood, Brent (2009). "Chapter 27: Halley VI Antarctic Research Station". Out of This World : The New Field of Space Architecture. Reston, Va.: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc. pp. 363–370. ISBN 978-1-563-47986-1. OCLC 762079294.

- Ross, Sandra; Richardson, Vicky (2013). Ice Lab: New Architecture and Science in Antarctica. London: The British Council. ISBN 978-0-863-55717-0. OCLC 854890064.

- Slavid, Ruth (2015). Ice Station: The Creation of Halley VI. Zurich: Park Books. ISBN 978-3-906-02766-1. OCLC 921659865.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Halley Station. |

- Official website British Antarctic Survey

- Designed By Petrel Engineering

- "Halley". Polar Conservation Organisation. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- "Halley Winterers 1956-present". ZFids. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- Videos

- Gemma Clarke, Structural Engineer with Faber Maunsell discusses working on Halley VI

- RIBA, Architecture and Climate Change talks: Hugh Broughton, Halley VI Research Station

- "Halley VI Research Station opened today". Kirk of the Antarctic (Blog at WordPress.com). 5 February 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

.svg.png)