Deception Island

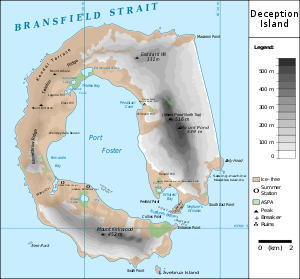

Map of Deception Island | |

Deception Island Location of Deception Island  Deception Island Deception Island (Antarctica) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Antarctica |

| Coordinates | 62°58′37″S 60°39′00″W / 62.97694°S 60.65000°WCoordinates: 62°58′37″S 60°39′00″W / 62.97694°S 60.65000°W |

| Area | 72 km2 (28 sq mi) |

| Length | 12 km (7.5 mi) |

| Width | 12 km (7.5 mi) |

| Administration | |

| Administered under the Antarctic Treaty System | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Uninhabited |

| Deception Island | |

|---|---|

Entrance to Deception Island, with Livingston Island in the background | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 576 m (1,890 ft) [1] |

| Prominence | 576 m (1,890 ft) |

| Coordinates | 62°58′37″S 60°39′00″W / 62.97694°S 60.65000°W |

| Geography | |

| Location | Antarctica |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Caldera |

| Last eruption | August 1970 |

Surgidero Iquique Antarctica | |

| Location |

Surgidero Iquique Deception Island South Shetland Islands Antarctica |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 62°58′09″S 60°42′33″W / 62.969287°S 60.709208°W |

| Year first constructed | n/a |

| Foundation | concrete base |

| Construction | fiberglass tower |

| Tower shape | cylindrical tower with lantern |

| Markings / pattern | white and orange horizontal bands tower[2] |

| Height | 4.5 metres (15 ft)[2] |

| Focal height | 114 metres (374 ft)[2] |

| Light source | solar power |

| Range | 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi)[2] |

| Characteristic | Fl W 5s.[2] |

| Admiralty number | G1383[2] |

| NGA number | 2743[2] |

| ARLHS number | SSI-002[3] |

Deception Island is an island in the South Shetland Islands archipelago, with one of the safest harbours in Antarctica. This island is the caldera of an active volcano, which seriously damaged local scientific stations in 1967 and 1969. The island previously held a whaling station; it is now a tourist destination and scientific outpost, with Argentine and Spanish research bases. While various countries have asserted sovereignty, it is still administered under the Antarctic Treaty System.

Geography

.jpg)

The island is approximately circular with a diameter of about 12 km (7.5 mi). A peak on the east side of the island, Mount Pond, has an elevation of 542 m (1,778 ft), and over half the island is covered by glaciers. The centre of the island is a caldera formed in a huge (VEI-6) eruption which has been flooded by the sea to form a large bay, now called Port Foster, about 9 km (5.6 mi) long and 6 km (3.7 mi) wide. The bay has a narrow entrance, just 230 m (755 ft) wide, called Neptune's Bellows. Adding to the hazard is Ravn Rock, which lies 2.5 m (8.2 ft) below the water in the middle of the channel. Just inside Neptune's Bellows lies the cove Whalers Bay, which is bordered by a large black sand beach.

Several maars line the inside rim of the caldera, with some containing crater lakes (including one named Crater Lake). Others form bays within the harbour, such as the 1 km (0.6 mi) wide Whalers Bay. Other features of the island include Mount Kirkwood, Fumarole Bay, Sewing-Machine Needles, Telefon Bay and Telefon Ridge.

A 2016 study on Ardley Island, 120km to the northeast, examined lake guano sediments and studied penguin population dynamics over 7,000 years. Three of five population growth phases were terminated by a sudden crash, due to volcanic eruptions from the active volcano of Deception Island.[4][5]

History

The first authenticated sighting of Deception Island was by the British sealers William Smith and Edward Bransfield from the brig Williams in January 1820; it was first visited and explored by the American sealer Nathaniel Palmer on the sloop Hero the following summer, on 15 November 1820. He remained for two days, exploring the central bay.[6]

Palmer named it "Deception Island" on account of its outward deceptive appearance as a normal island, when the narrow entrance of Neptune's Bellows revealed it rather to be a ring around a flooded caldera.[7][8]

Whaling and sealing

Over the next few years, Deception became a focal point of the short-lived fur sealing industry in the South Shetlands; the industry had begun with a handful of ships in the 1819–20 summer season, rising to nearly a hundred in 1821–22. While the island did not have a large seal population, it was a perfect natural harbour, mostly free from ice and winds, and a convenient rendezvous point. It is likely that some men lived ashore in tents or shacks for short periods during the summer, though no archaeological or documentary evidence survives to confirm this. Massive overhunting meant that the fur seals became almost extinct in the South Shetlands within a few years, and the sealing industry collapsed as quickly as it had begun; by around 1825 Deception was again abandoned.[6]

In 1829, the British Naval Expedition to the South Atlantic under the command of Captain Henry Foster in HMS Chanticleer stopped at Deception. The expedition conducted a topographic survey and scientific experiments, particularly pendulum and magnetic observations.[9] A watercolour made by Lieutenant Kendall of the Chanticleer during the visit may be the first image made of the island.[6] A subsequent visit by the American elephant-sealer Ohio in 1842 reported the first recorded volcanic activity, with the southern shore "in flames".[6]

The second phase of human activity at Deception began in the early twentieth century. In 1904, an active whaling industry was established at South Georgia, taking advantage of new technology and an almost untouched population of whales to make rapid profits. It spread south into the South Shetland Islands, where the lack of shore-based infrastructure meant that the whales had to be towed to moored factory ships for processing; these needed a sheltered anchorage and a plentiful supply of fresh water, both of which could be found at Deception. In 1906, the Norwegian-Chilean whaling company Sociedad Ballenera de Magallanes started using Whalers Bay as a base for a single ship, the Gobernador Bories.[6]

Other whalers followed, with several hundred men resident at Deception during the Antarctic summers and as many as thirteen ships operating in peak years. In 1908, the British government formally declared the island to be part of the Falkland Islands Dependencies and thus under British control, establishing postal services as well as appointing a magistrate and customs officer for the island. The magistrate was to ensure that whaling companies were paying appropriate licence fees to the Falklands government as well as ensuring adherence to catch quotas. A cemetery was built in 1908, a radio station in 1912, a hand operated railway also in 1912,[10] and a small permanent magistrate's house in 1914.[6] The cemetery, by far the largest in Antarctica, held graves for 35 men along with a memorial to 10 more presumed drowned.[11] These were not the only constructions; as the factory ships of the period were only able to strip the blubber from whales and could not use the carcasses, a permanent on-shore station was established by the Norwegian company Hvalfangerselskabet Hektor A/S in 1912 – it was estimated that up to 40% of the available oil was being wasted by the ship-based system. This was the only successful shore-based industry ever to operate in Antarctica, reaping high profits in its first years.[6] A number of exploring expeditions visited Deception during these years, including the Wilkins-Hearst expedition of 1928, when a Lockheed Vega was flown from a beach airstrip on the first successful flights in Antarctica.[6]

The development of pelagic whaling in the 1920s, where factory ships fitted with a slipway could tow aboard entire whales for processing, meant that whaling companies were no longer tied to sheltered anchorages. A boom in pelagic Antarctic whaling followed, with companies now free to ignore quotas and escape the costs of licences. This rapidly led to overproduction of oil and a collapse in the market, and the less profitable and more heavily regulated shore-based companies had trouble competing. In early 1931, the Hektor factory finally ceased operation, ending commercial whaling at the island entirely.[6]

Scientific research

Deception remained uninhabited for a decade but was revisited in 1941 by the British auxiliary warship HMS Queen of Bermuda, which destroyed the oil tanks and some remaining supplies in order to ensure it could not be used as a German supply base.[6] In 1942, an Argentinean party aboard the Primero de Mayo visited and left signs and painted flags declaring the site Argentinean territory; the following year, a British party with HMS Carnarvon Castle returned to remove the signs.[12]

In 1961, Argentina's president Arturo Frondizi visited the island to show his country's interest. Regular visits were made by other countries operating in the Antarctic, including the 1964 visit of the US Coast Guard icebreaker Eastwind, which ran aground inside the harbour.[13]

However, the volcano returned to activity in the late 1960s, destroying the existing scientific stations. Both British and Chilean stations were demolished, and the island was abandoned for several years. The final major eruption was reported by the Russian Bellingshausen station on King George Island and the Chilean station Arturo Pratt on Greenwich Island; both stations experienced major falls of ash on 13 August 1970.[14]

In 2000, there were two summer-only scientific stations, the Spanish Gabriel de Castilla Base[15] and the Argentinian Decepción Station.[16]

Remains of previous structures at Whalers Bay include rusting boilers and tanks, an aircraft hangar and the British scientific station house (Biscoe House), with the middle torn out by the 1969 mudflows. A bright-orange derelict airplane fuselage, which is that of a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter that belonged to the Royal Air Force, was recovered in 2004. There are plans to restore the airplane and return it to the island.[16]

The Russian cruise ship MV Lyubov Orlova ran aground at Deception Island on 27 November 2006.[17] She was towed off by the Spanish Navy icebreaker, Las Palmas and later became a ghost ship in the North Atlantic.

Research Stations

Aguirre Cerda Research Station

President Pedro Aguirre Cerda Station was a Chilean Antarctic base, located at Pendulum Cove in Deception Island in the South Shetland Islands, inaugurated in 1955.

Deception Station

Deception Station is an Argentine antarctic base located at Deception Island, South Shetland Islands. The station was founded on January 25, 1948, and was a year-round station until December 1967 when volcanic eruptions forced the evacuation of the base. Since then it is inhabited only during the summer.

Gabriel de Castilla

Gabriel de Castilla Base is a Spanish research station located on Deception Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. The station was constructed in 1990.[18]

Gutiérrez Vargas Refuge

The Gutiérrez Vargas Refuge, so called in memory of the aviation Captain who died on December 30, 1955, was located at 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from Aguirre Cerda Station and was inaugurated on February 12, 1956. Its purpose was to serve as a refuge for the members of the Station in case of fire. On December 4, 1967, the refuge was definitively abandoned, as was the Aguirre Cerda Station, due to a violent volcanic eruption. The remains of the refuge structure can still be seen on the beach where it was located.[19]

Station B

The island was finally reoccupied in early 1944 by a party of men from Operation Tabarin, a British expedition, who established a permanent scientific base named Station B (62°58′38″S 60°33′50″W / 62.977231°S 60.563809°W)[20]. This was occupied until 5 December 1967, when an eruption forced a temporary withdrawal. It was used again between 4 December 1968 and 23 February 1969, when further volcanic activity caused it to be abandoned.[21]

Environment

Deception Island has become a popular tourist stop in Antarctica because of its several colonies of chinstrap penguins, as well as the novel possibility of making a warm bath by digging into the sands of the beach. Mount Flora is the first site in Antarctica where fossilized plants were discovered.[22]

After the Norwegian Coastal Cruise Liner MS Nordkapp ran aground off the coast of Deception Island on 30 January 2007, fuel from the ship washed into a bay. Ecological damage has not yet been determined. On 4 February 2007 the Spanish Gabriel de Castilla research station on Deception Island reported that water and sand tests were clean and that they had not found signs of the oil, estimated as 500 to 750 litres (130 to 200 US gallons; 110 to 160 imperial gallons) of light diesel.

Deception Island exhibits some wildly varying microclimates. Some water temperatures reach 70 °C (158 °F). Near volcanic areas, the air can be as hot as 40 °C (104 °F).

Antarctic Specially Protected Areas

Some 11 terrestrial sites have been collectively designated an Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA 140), primarily for their botanic and ecological values, because the island has the greatest number of rare plant species of any place in the Antarctic. This is largely due to frequent volcanic activity creating new substrates for plant colonisation:[23]

- Collins Point (Site A) contains good examples of long-established vegetation, with high species diversity and several rarities.

- Crater Lake (Site B) has a scoria-covered lava tongue with a diverse cryptogamic flora, and exceptional development of turf-forming mosses.

- An unnamed hill at the southern end of Fumarole Bay (Site C) has several rare species of moss which have colonised the heated soil crust close to a line of volcanic vents.

- Fumarole Bay (Site D) is geologically complex with the most diverse flora on the island.

- West Stonethrow Ridge (Site E) supports several rare mosses, liverworts and lichens.

- Telefon Bay (Site F) has all its surfaces dating from 1967, thus allowing accurate monitoring of colonisation by plants and animals.

- Pendulum Cove (Site G) is another known-age site being colonised by mosses and lichens.

- Mount Pond (Site H) contains exceptional moss, liverwort and lichen communities.

- Perchue Cone (Site J) is an ash and cinder cone with rare mosses.

- Ronald Hill to Kroner Lake (Site K) is another known-age site being colonised by numerous cryptogam species, and with a unique algal community on the lake shore.

- South East Point (Site L) supports the most extensive population of Antarctic pearlwort known in the Antarctic region.

In addition, two marine sites in Port Foster have collectively been designated Antarctic Specially Protected Area 145, to protect their benthic communities.[24]

Important Bird Area

Baily Head, a prominent headland forming the easternmost extremity of the island, has been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports a very large breeding colony of chinstrap penguins (100,000 pairs). The 78 ha IBA comprises the ice-free headland and about 800 m of beach on either side of it. Other birds known to nest at the site include brown skuas, Cape petrels and snowy sheathbills.[25]

Gallery

_43.jpg)

See also

References

- ↑ "Deception Island". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 List of Lights, Pub. 111: The West Coasts of North and South America (Excluding Continental U.S.A. and Hawaii), Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, and the Islands of the North and South Pacific Oceans (PDF). List of Lights. United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 2017.

- ↑ "Antarctica". The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ↑ Jonathan Amos (11 April 2017). "Poo sediments record Antarctic 'penguin Pompeii'". BBC News Online.

- ↑ Stephen J. Roberts; Patrick Monien; Louise C. Foster; Julia Loftfield; Emma P. Hocking; Bernhard Schnetger; Emma J. Pearson; Steve Juggins; Peter Fretwell; Louise Ireland; Ryszard Ochyra; Anna R. Haworth; Claire S. Allen; Steven G. Moreton; Sarah J. Davies; Hans-Jürgen Brumsack; Michael J. Bentley; Dominic A. Hodgson (2017). "Past penguin colony responses to explosive volcanism on the Antarctic Peninsula". Nature Communications. 8 (14914). doi:10.1038/ncomms14914.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Dibbern, J. Stephen (2 September 2009). "Fur seals, whales and tourists: a commercial history of Deception Island, Antarctica". Polar Record. 46 (03): 210–221. doi:10.1017/S0032247409008651.

- ↑ Mills, William J. (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC Clio. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-57607-422-0.

- ↑ "SCAR Composite Gazetteer". www.data.aad.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ↑ Gordon Elliott Fogg, A history of Antarctic science, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 72–74

- ↑ Williams, Glynn. "Railways in Antarctica". Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ The Antarctic Treaty: measures adopted at the twenty-eighth consultative meeting held at Stockholm 6 – 17 June 2005 (Command Paper 7166). Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Office. July 2007. pp. 293–299. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ HMS Carnarvon Castle 1943

- ↑ From the log book of Christopher Malinger, Seaman on the USCGC Eastwind

- ↑ Fuchs, Vivian (1982). Of Ice and Men. Oswestry: Anthony Nelson. p. 294. ISBN 0-904614-06-9.

- ↑ "Gabriel De Castilla". New Zealand: Shades Stamp Shop. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- 1 2 "4 April – Otter Recovery". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ↑ "Cruise Ship MS Lyubov Orlova Runs Aground Needing Rescue in Antarctica". CruiseBruise. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ↑ "BAE Gabriel de Castilla" (in Spanish). Spanish National Research Council. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010.

- ↑ "Refugio Cabo Gutiérrez Vargas". Wikipedia Espanol. Wikimedia Foundation Inc. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ↑ Station B British Antarctic Survey

- ↑ Fuchs, Vivian (1982). Of Ice and Men. Oswestry: Anthony Nelson. pp. 291–2. ISBN 0-904614-06-9.

- ↑ Jurassic Liverworts from Mount Flora, Hope Bay, Antarctica

- ↑ "Parts of Deception Island, South Shetland Islands" (PDF). Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 140: Measure 3, Appendix 1. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2005. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ "Port Foster, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands" (PDF). Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 145: Measure 3, Appendix 2. Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2005. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- ↑ "Baily Head, Deception Island". BirdLife data zone: Important Bird Areas. BirdLife International. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

Further reading

- Official Deception Island website. Accessed 3 May 2007.

- Volcanic Activity. Accessed 4 June 2007.

- Deception Island, Eco-Photo Explorers. Accessed 3 May 2007.

- LeMasurier, W. E.; Thomson, J. W.; et al. (1990). Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Oceans. American Geophysical Union. ISBN 0-87590-172-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deception Island. |

- Images from Deception Island

- Página Web de la base Gabriel de Castilla

- "Steamed Ice and Frosted Lava" Account of a tourist visit to Deception Island

- British Deception Island station

- 21 photos of Deception island

- A visit to Deception Island, and other places on the Antarctic Peninsula, in 2002/3

- The 1970 eruption on Deception Island (Antarctica): eruptive dynamics and implications for volcanic hazards

- Global Volcanism Program: Deception Island

.jpg)

.svg.png)