Enosis

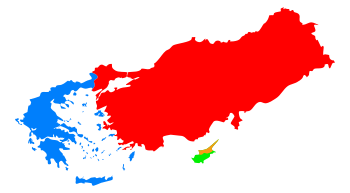

Enosis (Greek: Ένωσις, IPA: [ˈenosis], "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece, for incorporation of the regions they inhabit into the Greek state. Widely known is the case of the Greek-Cypriots for union of Cyprus into Greece. The idea of enosis is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist concept of a Greek state which dominated Greek politics following the creation of the modern Greek state in 1830. The Megali Idea was a project which called for the annexation of all ethnic Greek lands, parts of which had participated in the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s but which were unsuccessful and remained under foreign rule.

History

The boundaries of the Kingdom of Greece were originally established at the London Conference of 1832[1] following the Greek War of Independence.[2] The Duke of Wellington wanted the new state to be limited to the Peloponnese[3] because Britain wished to preserve as much of the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire as possible. The initial Greek state included little more than the Peloponnese, Attica and the Cyclades. Its population amounted to less than 1 million with three times as many ethnic Greeks living outside it, mainly in Ottoman territory.[4] Some of these aspired to be incorporated in the kingdom, and movements among them calling for enosis, or union with Greece, often achieved popular support. As the Ottoman Empire declined the Greek state expanded with a number of territorial gains.

The Ionian Islands had been placed under British protection as a result of the Treaty of Paris in 1815, but once Greek independence was established after 1830 the islanders began to resent foreign colonial rule and to press for Enosis. Britain transferred the islands to Greece in 1864.

Thessaly remained under Ottoman control after the formation of the Kingdom of Greece. Although parts of the territory had participated in the initial uprisings in the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the revolts had been swiftly crushed. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 Greece remained neutral, as a result of assurances by the Great Powers that her territorial claims on the Ottoman Empire would be considered after the war. In 1881 Greece and the Ottoman Empire signed the Convention of Constantinople which created a new Greco-Turkish border, incorporating most of Thessaly into Greece.

Crete rebelled against Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866-69 using the motto "Crete, Enosis, Freedom or Death". The Cretan State was established following the intervention of the Great Powers, and Cretan union with Greece occurred de facto in 1908 and de jure in 1913 through the Treaty of Bucharest.

An unsuccessful Greek uprising in Macedonia against Ottoman rule had taken place during the Greek War of Independence. There was a rebellion in 1854 aiming to unite Macedonia with Greece, but it failed.[5] The Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 awarded nearly all of Macedonia to Bulgaria. This resulted in the 1878 Greek Macedonian rebellion and the reversal of the award at the Treaty of Berlin (1878), leaving the territory in Ottoman hands. There followed the protracted Macedonian Struggle between Greeks and Bulgarians in the region, the resultant guerrilla war only coming to an end with the Ottoman revolution of Young Turks in July 1908. Bulgarian and Greek rivalries over Macedonia became part of the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, with the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest awarding Greece large parts of Macedonia, including Thessaloniki. The Treaty of London (1913) awarded southern Epirus to Greece, the Epirus region having risen up against Ottoman rule during the Epirus Revolt of 1854 and the Epirus Revolt of 1878.

In 1821, several parts of Western Thrace rebelled against Ottoman rule, participating in the Greek War of Independence. During the Balkan Wars, Western Thrace was occupied by Bulgarian troops and in 1913 Bulgaria gained Western Thrace under the terms of the Treaty of Bucharest. Following World War I, Western Thrace was withdrawn from Bulgaria under the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and put temporarily under Allied management before being given to Greece at the San Remo conference in 1920.

Following the conclusion of World War I, Greece began the occupation of Smyrna and surrounding areas of Western Anatolia in 1919 at the invitation of the victorious Allies of World War I, particularly David Lloyd George the British Prime Minister. The occupation was given official status in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, with Greece being awarded most of Eastern Thrace and a mandate to govern Smyrna and its hinterland.[6] Smyrna was declared a protectorate in 1922. However, the attempted enosis failed when the new Turkish Republic prevailed in the resulting Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, after which most Anatolian Christians who had not already fled during the war were forced to relocate to Greece in the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

Most of the Dodecanese islands were slated to become part of the new Greek state in the London Protocol of 1828, but when Greek independence was recognised in the London Protocol of 1830, the islands were left outside the new Kingdom of Greece. They were subsequently occupied by Italy in 1912 and held until World War II, after which they became a British military protectorate. The islands were formally united with Greece by the 1947 Treaty of Peace with Italy, despite objections from Turkey which also desired them.

The Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed in 1914 by ethnic Greeks in Northern Epirus, the area having been incorporated into Albania following the Balkan Wars. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916 and unsuccessfully tried to annexe it in March 1916,[7] but in 1917 Greek forces were driven from the area by Italy, who took over most of Albania.[8] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece, but following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War the area reverted to Albanian control.[9] Following Italy's invasion of Greece from the territory of Albania in 1940 and the successful Greek counterattack, the Greek army briefly held Northern Epirus for a six-month period until the German invasion of Greece in 1941. Tensions between Greece and Albania remained high during the Cold War, but relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between the two countries.[7] In modern times, apart from Cyprus, the call for enosis is most often heard among part of the Greek community living in southern Albania.[10]

Cyprus

Inception of Cypriot enosis

In 1828, modern Greece’s first president Ioannis Kapodistrias, whose maternal ancestors were Greek Cypriots,[11][12] called for union of Cyprus with Greece, and numerous minor uprisings took place.[13]

The enosis movement was the outgrowth of nationalist awareness among the ethnically Greek population of Cyprus (around 80%[14] between 1882 and 1960), coupled with the growth of the anti-colonial movement throughout the British Empire after World War II. In fact, the anti-colonial movement in Cyprus was identified with the enosist movement, enosis being, in the minds of the Hellenic population of Cyprus, the only natural outcome of the liberation of the Cypriot people from Ottoman rule and later the British rule. A string of British proposals for local autonomy under continued British suzerainty were roundly rejected.

1940s and 1950s

The idea of enosis was systematically implanted into the minds of Greek Cypriot youth through education. Greek Cypriot schools that aligned themselves with the curriculum in Greece were recognised by the Greek government and the graduates of these schools were accepted into Greek universities without any exams. As such, Greek Cypriot schools put emphasis on the idea of being part of a greater Greek nation and the realisation of Megali Idea to make Greece great again. They taught students that they were Greeks and should welcome enosis. In the 1940s and '50s, textbooks portrayed Turks as enemies of Greeks and claimed that Greek Cypriots were enslaved by the British. Students were made to take an oath of allegiance to the Greek flag on the Flag Day and students at Flag Day celebrations marched chanting anti-Turkish slogans, such as "the heads of Turks must be cut off and their bodies thrown in filth". Students pledged their loyalty to the Greek king at the Boy Scouts, which was later banned by the British. Inter-communal periodicals, published by the British, were prevented from being accessed by students and teachers were pressured to actively promote enosis as they feared retribution by the Church.[15]

In December 1949, the Cypriot Orthodox Church asked the British colonial government to put the Enosis question to a referendum, on the basis of the right of the Cypriot population for self-determination. Even though the UK was an ally of Greece during WW2 and had recently supported the Greek government during the Greek civil war, the British colonial government refused. The Church then proceeded to organise its own unofficial enosis referendum which would take place in churches. The referendum took place on the two consecutive Sundays of 15 and 22 January 1950, with an overwhelming majority 95.7% of Greeks signing in favour of extricating the island from the British Empire and annexing it to the Kingdom of Greece.[16] Later, there were accusations that the local Greek Orthodox church had told its congregation that if it did not vote in favour of Enosis that would have meant excommunication from the church. Unlike modern elections and referendums, which are decided by secret ballot, the 1950 referendum amounted to a public collection of signatures.[17][18] An obvious reason for this could be that, given the unofficial status of the referendum, a secret ballot would be easier to dispute than an eponymous one (collection of signatures).

After the referendum, a delegation was formed with the aim of the international distribution of the referendum documents. The representatives managed to deliver the documents with the signatures to the Greek parliament, London and the United Nations headquarters in New York. In 1954, Greece made its first formal request to the UN for the implementation of "the principle of equal rights and of self-determination of the peoples" in the case of the Cypriot population. Until 1958, four other relative requests were made- unsuccessfully- by the Greek government to the United Nations.[19]

In 1955, the resistance movement EOKA was formed in Cyprus in order to end British rule and annexe the island to Greece. The anti-colonial, liberation struggle lasted until 1959. By then, it was argued by many that enosis was politically unfeasible due to the presence of a strong Turkish minority and its increasing assertiveness. Instead, the creation of an independent state with elaborate power-sharing arrangements among the two communities was agreed upon in 1960, and the fragile Republic of Cyprus was born.

After independence

The idea of union with Greece was not immediately abandoned, though. During the campaign for the 1968 presidential elections, the incumbent President Makarios III said that enosis was "desirable" whereas independence was "possible". This differentiated him from the hardline pro-enosis elements which formed EOKA B and participated in a military coup against him in 1974. The coup was organised and supported by the Greek government, which was still in the hands of a military junta. The Turkish government responded to the change of status quo by the invasion of Cyprus. The result of the events of 1974 was the geographic partition of Cyprus, followed by massive population transfers. The coup and subsequent events seriously undermined the enosis movement. The departure of Turkish Cypriots from the areas which remained under the Republic's effective control resulted in a homogeneous Greek Cypriot society in the southern two-thirds of the island. Greek Cypriots started to strongly identify with the Republic of Cyprus, which, since the partition, has lain under their community's exclusive political control.

In 2017 the Cypriot Parliament passed a law allowing for the celebration of the 1950 Cypriot enosis referendum in Greek Cypriot public schools.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ "On This Day In History: Independence Of Greece Is Recognized By The Treaty Of London – On May 7, 1832". Ancient Pages. 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Anagnostopoulos, Nikodemos (2017). Orthodoxy and Islam: Theology and Muslim–Christian Relations in Modern Greece and Turkey. Routledge. ISBN 9781315297910.

- ↑ Cooke, Tim (2010). The New Cultural Atlas of the Greek World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 174. ISBN 9780761478782.

- ↑ Hupchick, D (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Springer. p. 223. ISBN 9780312299132.

- ↑ Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: prelude to collapse, 1839-1878. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 249–252. ISBN 9783515076876.

- ↑ Frucht, Richard. Eastern Europe. Volume 2. p. 888. ISBN 9781576078006.

- 1 2 Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie, ed. The new Albanian migrations. Sussex Academic Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781903900789.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801-1927. Routledge. pp. 543–544. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- ↑ Stein, Jonathan (2000). The politics of national minority participation in post-communist Europe : state-building, democracy, and ethnic mobilization. Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe. p. 180. ISBN 9780765605283.

- ↑ Crawley C. W. (1957). Cambridge Historical Journal, 1957, vol. 13, no. 2, "John Capodistrias and the Greeks before 1821". Cambridge University Press. p. 166. OCLC 478492658.

…Capodistrias…his mother, Adamantine Gonemes, who came of a substantial Greek family in Epirus

- ↑ Woodhouse, Christopher Montague (1973). Capodistria: the founder of Greek independence. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–5. OCLC 469359507.

The family of Gonemis or Golemis, which originated in Cyprus, had moved to Crete when Cyprus fell in the 16th century; then to Epirus when Crete fell in the 17th, settling near Argyrokastro in modern Albania; and finally to Corfu. This Island when Cyprus fell in the 16th century ; then to Epirus when Crete fell in the 17th, settling near Argyrokastro in modern Albania; and finally to Corfu.

- ↑ William Mallinson, Bill Mallinson (2005). Cyprus: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 10. ISBN 9781850435808.

ISBN 1-85043-580-4" "In 1828, modern Greece’s first president, Count Kapodistria, called for union of Cyprus with Greece, and various minor uprising took place.

- ↑ "Cyprus - Population". Country-data.com. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ↑ Lange, Matthew (2011). Educations in Ethnic Violence: Identity, Educational Bubbles, and Resource Mobilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–5. ISBN 1139505440.

- ↑ Zypern, 22. Januar 1950 : Anschluss an Griechenland Direct Democracy

- ↑ "ΕΝΩΤΙΚΟ ΔΗΜΟΨΗΦΙΣΜΑ 15-22/1/1950 (in Greek, includes image of a signature page)". Cyprus.novopress.info. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ↑ "Κύπρος: το ενωτικό δημοψήφισμα που έγινε με υπογραφές (in Greek)". Hellas.org. 1967-04-21. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ↑ Emis i Ellines- Polemiki istoria tis Synhronis Elladas ("Greeks- War History of Modern Greece"), Skai Vivlio press, 2008, chapter by nikos Papanastasiou "The Cypriot Issue", p. 125, 142

- ↑ "Turkey slams Greek Cyprus' Enosis move". Hürriyet Daily News. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2018.