Greece during World War I

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the Kingdom of Greece remained a neutral nation. Nonetheless, Greek forces in October 1914 occupied Northern Epirus, a territory of southern Albania that it claimed for its own, at a time when the new Principality of Albania was in turmoil. At the same time, the Kingdom of Italy occupied Sazan Island, another Albanian possession, and later that December the Albanian port of Vlorë.

Road to War

Background

Greece had emerged victorious from the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars, with her territory almost doubled, but found itself in a difficult international situation. The status of the Greek-occupied eastern Aegean islands was left undetermined, and the Ottoman Empire continued to claim them, leading to a naval arms race and mass expulsions of ethnic Greeks from Anatolia. In the north, Bulgaria, defeated in the Second Balkan War, harbored revanchist plans against Greece and Serbia.

Greece and Serbia were bound by a treaty of alliance, signed on 1 June 1913, which promised mutual military assistance in case of an attack by a third party, referring to Bulgaria.[1] However, in the spring and summer of 1914, Greece found itself in a confrontation with the Ottoman Empire over the status of the eastern Aegean islands, coupled with a naval race between the two countries and persecutions of the Greeks in Asia Minor. On 11 June, the Greek government issued an official protest to the Porte, threatening a breach of relations and even war, if the persecutions were not stopped. On the next day Greece requested the assistance of Serbia, if matters came to a head, but on 16 June, the Serbian government replied that due to the country's exhaustion after the Balkan Wars, and the hostile stance of Albania and Bulgaria, Serbia could not commit to Greece's aid, and recommended that war be avoided.[2] On 19 June 1914, the Army Staff Service, under Lt. Colonel Ioannis Metaxas, presented its study on military options against Turkey: the only truly decisive manoeuvre, a landing of the entire Hellenic Army in Asia Minor, was impossible due to the hostility of Bulgaria; instead, Metaxas proposed the sudden occupation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, without a prior declaration of war, the clearing of the Dardanelles, and the occupation of Constantinople so as to force the Ottomans to negotiate.[3] However, on the previous day, the Ottoman government had suggested mutual talks, and the tension eased enough for Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos and the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Said Halim Pasha, to meet in Brussels in July.[4]

In the event, the anticipated conflict would emerge from a different quarter altogether: the Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June led to the declaration of war by Austria-Hungary on Serbia and the outbreak of the First World War a month later, on 28 July 1914.[5]

Between war and neutrality, 1914–1916

Already on 25 July, the Serbian government requested Greece's aid by the terms of the alliance, in the case of an Austrian and Bulgarian attack. On 2 August, Venizelos replied that Greece would remain a friendly neutral, since an important clause in the alliance agreement was rendered impossible: Serbia had undertaken to provide 150,000 troops in the area of Gevgelija to guard against a Bulgarian attack. Furthermore, if Greece sent her army to fight the Austrians along the Danube, this would only incite a Bulgarian attack against both countries, with insufficient forces to oppose it.[6] On the other hand, Venizelos and King Constantine I were in agreement when they rejected a German demand on 27 July to join the Central Powers.[7] In the meantime, the Ottomans drifted towards the German camp, and on 29 October 1914 entered the war on the side of the Central Powers.[8]

Early negotiations between Greece and the Allies

On 14 August 1914, Venizelos submitted a request to Britain, France, and Russia on their stance towards Greece, should the latter aid Serbia against Bulgaria and Turkey. This was followed on 18 August by a formal offer of alliance. Only Britain replied to Venizelos' request, on 19 August, to the effect that as long as the Ottomans remained neutral, Greece should as well; if Turkey entered the war, however, she would be welcome as an ally. The Allied governments were lukewarm to Venizelos' proposals, since they hoped to entice Bulgaria on their side, even offering territorial concessions at the expense of Serbia, Greece, and Romania; while Russia in particular considered her interests best served if Greece remained neutral.[8] On 2 December, Serbia repeated its request for Greek assistance, which was supported by the Allied governments. Venizelos asked Metaxas for the Army Staff Service's evaluation of the situation; the opinion of the latter was that without a simultaneous entry of Romania into the war on the side of the Allies, Greece's position was too risky. Following the firm refusal of Romania to be drawn into the conflict at this time, the proposal was scuttled.[9]

On 24 January 1915, the British offered Greece "significant territorial concessions in Asia Minor" if it would enter the war to support Serbia, and in exchange for satisfying some of the Bulgarian territorial demands in Macedonia (Kavala, Drama, and Chrysoupolis) in exchange for Bulgarian entry into the war on the Allies' side.[10] Venizelos argued in favour of the proposal, but again the opinion of Metaxas was negative, for much the same reasons: the Austrians were likely to defeat the Serbian army before a Greek mobilization could be completed, Bulgaria was likely to flank any Greek forces fighting against the Austrians, while a Romanian intervention would not be decisive. Metaxas judged that even if Bulgaria joined the Allies, it still would not suffice to shift the balance in the Allies' favour in Central Europe, and recommended the presence of four Allied army corps in Macedonia as the minimum necessary force for any substantial aid to the Greeks and Serbs. Furthermore, a Greek entry into the war would once again expose the Greeks of Asia Minor to Turkish reprisals.[11] Venizelos rejected this report, and recommended entry into the war in a memorandum to the King, provided that Bulgaria and Romania also joined the Allies. The situation changed almost immediately when a large German loan to Bulgaria, and the conclusion of a Bulgarian–Ottoman agreement for the transshipment of war material through Bulgaria became known. The Allies reiterated their request on 15 February, but Greece again refused, and even offered to send Anglo-French troops to Thessaloniki; the Greek government's final decision again hinged on the stance of Romania, which again decided to remained neutral.[12]

However, in February, the Allied attack on Gallipoli began, with naval bombardments of the Ottoman forts there.[13] Venizelos decided to offer an army corps and the entire Greek fleet to assist the Allies, making an official offer on 1 March, despite the King's reservations. This caused Metaxas to resign on the next day, while meetings of the Crown Council (the King, Venizelos, and the living former prime ministers) on 3 and 5 March proved indecisive. King Constantine decided to keep the country neutral, whereupon Venizelos submitted his resignation on 6 March 1915.[14] He was replaced by Dimitrios Gounaris, who formed his government on 10 March.[15] On 12 March, the new government suggested to the Allies its willingness to join them, under certain conditions. The Allies, however, expected a victory of Venizelos in the forthcoming elections, and were in no hurry to commit themselves. Thus on 12 April they replied to Gounaris' proposal, offering territorial compensation in vague terms the Aydin Vilayet—anything more concrete was impossible, since at the same time the Allies were negotiating with Italy on her own demands in the same area—while making no mention of Greece's integrity vis-a-vis Bulgaria, as Venizelos had already proven himself willing to countenance the cession of Kavala to Bulgaria.[16]

Venizelos returns to power; Bulgaria and Greece mobilize

The Liberal Party won the 12 June elections, and Venizelos again formed a government on 30 August, with the firm intention of bringing Greece into the war on the side of the Allies.[17] In the meantime, on 3 August, the British formally requested, on behalf of the Allies, the cession of Kavala to Bulgaria; this was rejected on 12 August, before Venizelos took office.[17]

On 6 September, Bulgaria signed a treaty of alliance with Germany, and a few days later mobilized against Serbia. Venizelos ordered a Greek counter-mobilization on 23 September.[18] 24 classes of men were called to arms, but the mobilization proceeded with numerous difficulties and delays, as infrastructure or even military registers were lacking in the areas recently gained during the Balkan Wars. Five army corps and 15 infantry divisions were eventually mobilized, but there were insufficient officers to man all the units, reservists tarried in presenting themselves to the recruitment stations, and there was a general lack of transport means to bring them to their units. In the end, only the III, IV, and V Corps were assembled in Macedonia, while the divisions of I and II Corps largely remained behind in "Old Greece". Likewise, III Corps' 11th Infantry Division remained in Thessaloniki, rather than proceed to the staging areas along the border.[19]

Allied landing at Thessaloniki

As a Bulgarian entry into the war on the side of the Central Powers loomed, the Serbs requested Greek assistance by the terms of the treaty of alliance. Again, however, the issue of Serbian assistance against Bulgaria around Gevgelija was raised: even after mobilization, Greece could muster only 160,000 men, against 300,000 Bulgarians. As the Serbs were too hard-pressed to divert any troops to assist Greece, on 22 September Venizelos asked the Anglo-French to assume that role.[20] The Allies gave a favourable reply on 24 September, but they did not have the 150,000 men required; as a result the King, the Army Staff Service, and large part of the opposition preferred to remain neutral until the Allies could guarantee effective support. Venizelos, however, asked the French ambassador to send Allied troops to Thessaloniki as quickly as possible, but to give a warning of 24 hours to the Greek government; Greece would lodge a formal complaint at the violation of its neutrality, but then accept the fait accompli. As a result, the French 156th Division and the British 10th Division were ordered to embark from Gallipoli for Thessaloniki.[21]

The Allies did not inform Athens, however, leading to a tense stand-off: when the Allied warships arrived in the Thermaic Gulf on the morning of 30 September, the local Greek commander, the head of III Corps, Lt. General Konstantinos Moschopoulos, unaware of the diplomatic manoeuvres, refused them entry pending instructions from Athens. Venizelos was outraged that the Allies had not informed him as agreed, and refused to allow their disembarkation. After a tense day, the Allies agreed to halt their approach, until the Allied diplomats could arrange matters with Venizelos in Athens. Finally, during the night of 1/2 October, Venizelos gave the green light for the disembarkation, which began on the same morning. The Allies issued a communique justifying their landing as a necessary measure to secure their lines of communication with Serbia, to which the Greek government replied with a protest, but no further actions.[22]

King Constantine dismisses Venizelos

Following this event, Venizelos presented his case for participation in the war to Parliament, securing 152 votes in favour to 102 against on 5 October. On the next day, however, King Constantine dismissed Venizelos, and called upon Alexandros Zaimis to form a government.[23] Zaimis was favourably disposed to the Allies, but the military situation was worse than a few months before: the Serbs were stretched to breaking point against the Austro-Germans, Romania remained staunchly neutral, Bulgaria was on the verge of entering the war on the side of the Central Powers, and the Allies had few reserves to provide any practical aid to Greece.[24] Greek–Serbian staff talks ended fruitlessly, and even an offer of Cyprus by the British on 16 October was not enough to alter the new government's stance.[24]

Collapse of Serbia, creation of the Salonika Front

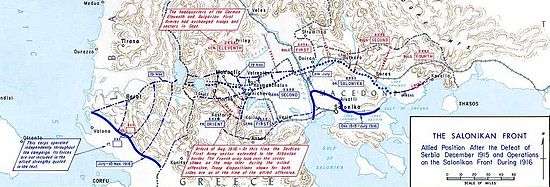

Indeed, on 7 October the Austro-German forces under August von Mackensen began their decisive offensive against Serbia, followed by a Bulgarian attack on 14 October, without prior declaration of war. The Bulgarian attack cut off the Serbian retreat south to Greece, forcing the Serbian army to retreat via Albania.[25] The French commander-designate in Thessaloniki, Maurice Sarrail, favoured a large-scale Allied operation in Macedonia against Bulgaria, but available forces were few; the British especially were loath to evacuate Gallipoli, while the French commander-in-chief, Joseph Joffre, was reluctant to divert forces from the Western Front. In the end, it was agreed to send 150,000 troops to the "Salonika Front", approximately half each French—the "Armée d'Orient" under Sarrail, with the 156th, 57th, and 122nd divisions—and British—the "British Salonika Force" under Bryan Mahon, with 10th Division, XII Corps and XVI Corps.[26]

In the early summer of 1916, the Athens government under King Constantine handed over Fort Rupel to the Germans, believing it a neutral act, though claimed as a betrayal by the Venizelists. Nonetheless, the Allies still tried to swing the official Athens government to their side. From their positions in Greece, Allied forces --(British, French, Russian, Italian, and Serb) fought the war from Greek territory, engaging Bulgarian forces when they invaded Greece in August 1916 in the Battle of Struma.

Greece joins the war (1916-17)

In August 1916, Venizelist officials staged a coup d'état that prompted Venizelos to leave Athens. He returned in October 1916 and set up a rival government in Thessaloniki, the so-called Provisional Government of National Defence. Entente and Venizelist efforts to persuade the "official" royal government in Athens to abandon its neutrality and join them failed, and relations irreparably broke down during the Noemvriana, when Entente and Venizelist troops clashed with royalists in the streets of the Greek capital. The royalist officers of the Hellenic Army were cashiered, and troops were conscripted to fight under Venizelist officers, as was the case with the Royal Hellenic Navy. Still, King Constantine, who enjoyed the protection of the Russian Tsar as a relative and fellow monarch, could not be removed until after the February Revolution in Russia removed the Russian monarchy from the picture. In June 1917, King Constantine abdicated from the throne, and his second son, Alexander, assumed the throne as king (despite the wishes of most Venizelists to declare a Republic). Venizelos assumed control of the entire country, while royalists and other political opponents of Venizelos were exiled or imprisoned. Greece, by now united under a single government, officially declared war against the Central Powers on 28 June 1917 and would eventually raise ten divisions for the Entente effort, alongside the Royal Hellenic Navy.

Participation in the war

1917 Greek war poster

1917 Greek war poster Hellenic Army at Strymon river, 1917

Hellenic Army at Strymon river, 1917 Prime Minister Venizelos in Paris during the war (1917)

Prime Minister Venizelos in Paris during the war (1917) Venizelos inspects units at the Macedonian front, 1918

Venizelos inspects units at the Macedonian front, 1918

The Macedonian Front stayed mostly stable throughout the war. In May 1918, Greek forces attacked Bulgarian forces and defeated them at the Battle of Skra-di-Legen on 30 May 1918. Later in 1918, the Allied forces drove their offensive from Greece into occupied Serbia. In September of that year, Allied forces (French, Greek, Serb, Italian, and British troops), under the command of French General Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, broke through German, Austro-Hungarian, and Bulgarian forces along the Macedonian front. Bulgaria later signed the Armistice of Salonica with the Allies in Thessaloniki on 29 September 1918. By October, the Allies including the Greeks under French General Louis Franchet d'Espèrey had taken back all of Serbia and were ready to invade Hungary until the Hungarian authorities offered surrender.

The Greek military suffered an estimated 5,000 deaths from their nine divisions that participated in the war.[27]

After the war

As Greece emerged victorious from World War I, it was rewarded with territorial acquisitions, specifically Western Thrace (Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine) and Eastern Thrace and the Smyrna area (Treaty of Sèvres). Greek gains were largely undone by the subsequent Greco-Turkish War of 1919 to 1922.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 6.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 8.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 6, 17.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 17.

- 1 2 Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 18.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 20.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 20–26.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 29.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 41.

- 1 2 Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 43–45.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 42–43, 45.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, p. 49.

- 1 2 Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Επίτομη ιστορία συμμετοχής στον Α′ Π.Π., 1993, pp. 51–54.

- ↑ Gilbert, 1994, p 541

- ↑ Petsalis-Diomidis, Nicholas. Greece at the Paris Peace Conference/1919. Inst. for Balkan Studies, 1978.

Sources

- Abbott, G. F. (2008). Greece and the Allies 1914–1922. London: Methuen & co. ltd. ISBN 978-0-554-39462-6.

- Clogg, R. (2002). A Concise History of Greece. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00479-9.

- Dutton, D. (1998). The Politics of Diplomacy: Britain and France in the Balkans in the First World War. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-079-7.

- Fotakis, Z. (2005). Greek naval strategy and policy, 1910–1919. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35014-3.

- Kitromilides, P. (2006). Eleftherios Venizelos: The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2478-3.

- Επίτομη ιστορία της συμμετοχής του Ελληνικού Στρατού στον Πρώτο Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο 1914 - 1918 [Concise History of the Hellenic Army's Participation in the First World War 1914–1918] (in Greek). Athens: Hellenic Army History Directorate. 1993.

- Gilbert, Martin (1994). The First World War.

- Kaloudis, George. "Greece and the Road to World War I: To What End?." International Journal on World Peace 31.4 (2014): 9+.

- Keegan, John (1998). The First World War.

- Leon, George B. Greece and the First World War: from neutrality to intervention, 1917-1918 (East European Monographs, 1990)

- Strachan, Hew (1998). World War I: A History.