Filiki Eteria

| |

| Motto |

Ελευθερία ή θάνατος Eleftheria i thanatos Freedom or Death |

|---|---|

| Formation | 14 September 1814 |

| Purpose | Preparation of the Greek War of Independence |

| Location |

|

| Fields |

Nationalism Egalitarianism Europeanism |

Key people |

Emmanuil Xanthos (founder) Nikolaos Skoufas (founder) Athanasios Tsakalov (founder) Alexander Ypsilantis (leader) Alexandros Mavrokordatos Theodoros Kolokotronis Anthimos Gazis Germanos III of Old Patras Emmanouel Pappas |

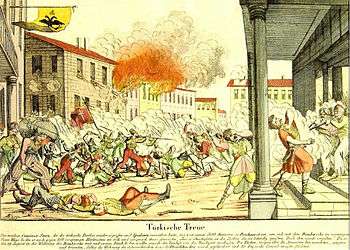

Filiki Eteria or Society of Friends (Greek: Φιλική Εταιρεία or Εταιρεία των Φιλικών) was a secret organization founded in 1814 in Odessa, whose purpose was to overthrow the Ottoman rule of Greece and establish an independent Greek state.[1] Society members were mainly young Phanariot Greeks from Constantinople and the Russian Empire, local political and military leaders from the Greek mainland and islands, as well as several Orthodox Christian leaders from other nations that were under Hellenic influence, such as Karađorđe from Serbia [2] Tudor Vladimirescu from Romania, and Hellenized Albanian military commanders.[3][4] One of its leaders was the prominent Phanariote Prince Alexander Ypsilantis.[5] The Society initiated the Greek War of Independence in the spring of 1821.[6]

Translations and transliterations

The direct translation of the word "Filiki" is "Friendly" and the direct translation of "Eteria" is "Society" (or "Company" or "Association"). The name of Filiki Eteria has been transliterated, in numerous publications, with one of the spelling variants suggested by (F/Ph)ilik(i/e), followed either by one of the spelling variants that (Et(e/ai)r(e)ia) suggests, or by Hetairia.

Foundation

In the context of ardent desire for independence from Turkish occupation, and with the explicit influence of similar secret societies elsewhere in Europe, three Greeks came together in 1814 in Odessa to decide the constitution for a secret organization in freemasonic fashion. Its purpose was to unite all Greeks in an armed organization to overthrow Turkish rule. The three founders were Nikolaos Skoufas from the Arta province, Emmanuil Xanthos from Patmos and Athanasios Tsakalov from Ioannina.[1] Soon after they initiated a fourth member, Panagiotis Anagnostopoulos from Andritsaina.

Skoufas met with Konstantinos Rados, who was initiated into Carbonarism. Xanthos was initiated into a Freemasonic Lodge at Lefkada ("Society of Free Builders of Saint Mavra"), while Tsakalov was a founding member of the Hellenoglosso Xenodocheio (Greek: Ελληνόγλωσσο Ξενοδοχείο, meaning Greek-speaking Hotel) an earlier but unsuccessful society for the liberation of Greece.[7]

At the start, between 1814 and 1816, there were roughly twenty members. During 1817, the society initiated members from the diaspora Greeks of Russia and the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. The lord (hospodar) of Moldavia Michael Soutzos himself, became a member.[8] Massive initiations began only in 1818 and by early 1821, when the Society had expanded to almost all regions of Greece and throughout Greek communities abroad, the membership numbered in thousands.[9] Among its members were tradesmen, clergy, Russian consuls, Ottoman officials from Phanar and revolutionary Serbs, most notably, the leader of the First Serbian Uprising, father of the modern Serbia and founder of the Karadjordjevic dynasty Karageorge Petrovic.[9][10] Members included primary instigators of the Greek revolution, notably Theodoros Kolokotronis, Odysseas Androutsos, Dimitris Plapoutas and the metropolitan bishop Germanos of Patras.

Hierarchy and initiation

Filiki Eteria was strongly influenced by Carbonarism and Freemasonry.[7] The team of leaders was called the "Invisible Authority" (Αόρατος Αρχή) and from the start it was shrouded in mystery, secrecy and glamour. It was generally believed that a lot of important personalities were members, not only eminent Greeks, but also notable foreigners such as the Tsar of Russia Alexander I. The reality was that initially, the Invisible Authority comprised only the three founders. From 1815 until 1818, five more were added to the Invisible Authority, and after the death of Skoufas' another three more. In 1818, the Invisible Authority was renamed to the "Authority of Twelve Apostles" and each Apostle shouldered the responsibility of a separate region.

The organisational structure was pyramid-like with the "Invisible Authority" coordinating from the top. No one knew or had the right to ask who created the organisation. Commands were unquestionably carried out and members did not have the right to make decisions. Members of the society came together in what was called a "Temple" with four levels of initiation: a) Brothers (Αδελφοποίητοι) or Vlamides (Βλάμηδες), b) the Recommended (Συστημένοι), c) the Priests (Ιερείς) and d) the Shepherds (Ποιμένες).[11] The Priests were charged with the duty of initiation.[12]

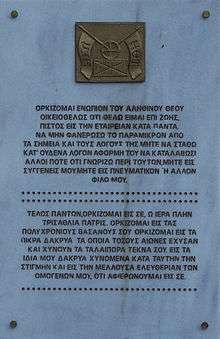

| “ | I swear in the name of truth and justice, before the Supreme Being, to guard, by sacrificing my own life, and suffering the hardest toils, the mystery, which shall be explained to me and that I shall respond with the truth whatever I am asked. | ” |

| — The Oath of Initiation in to the Filiki | ||

When the Priest approached a new member, it was first to make sure of his patriotism and catechize him in the aims of society; the last stage was to put him under the lengthy principal oath, called the Great Oath (Μέγας Όρκος).[12] Much of the essence of it was contained in its conclusion:[11]

| “ | Last of all, I swear by Thee, my sacred and suffering Country,— I swear by thy long-endured tortures,— I swear by the bitter tears which for so many centuries have been shed by thy unhappy children, by my own tears which I am pouring forth at this very moment,— I swear by the future liberty of my countrymen, that I consecrate myself wholly to thee; that hence forward thou shall be the cause and object of my thoughts, thy name the guide of my actions, and thy happiness the recompense of my labours. | ” |

| — Conclusion of the Great Oath of the Filiki | ||

When the above was administered the Priest then uttered the words of acceptance of the novice as a new member:[12]

| “ | Before the face of the invisible and omnipresent true God, who in his essence is just, the avenger of transgression, the chastizer of evil, by the laws of the Eteria Filiki, and by the authority with which its powerful priests have intrusted me, I receive you, as I was myself received, into the bosom of the Eteria. | ” |

| — words of acceptance into Filiki | ||

Afterwards the initiated were considered neophyte members of the society, with all the rights and obligations of his rank. The Priest immediately had the obligation to reveal all the marks of recognition between the Vlamides or Brothers. Vlamides and Recommended were unaware of the revolutionary aims of the organisation. They only knew that there existed a society that tried hard for the general good of the nation, which included in its ranks important personalities. This myth was propagated deliberately, in order to stimulate the morale of members and also to make proselytism easier.

Members

Members in the secret society divided to three parts: a) Etairoi: Shepherds with important duty, b) Apostles: Priests with important duty, and c) all other members.[13]

| Etairoi | Apostles |

|---|---|

|

|

| 1 In source referended as Christodoulos Perraivos (p. 44). 2 In source referended as N. Galatis (p. 44) and Galanis (p. 45). 3 In source referended as Georgios Katakazis (p. 44). † Members who were killed as traitors (p. 45). | |

| Source: List of 12 Etairoi and 15 Apostles, sorted by their initiation date.[13] | |

Change of leadership

In 1818, the seat of Filiki Eteria had migrated from Odessa to Constantinople, and Skoufas' death had been a serious loss. The remaining founders attempted to find a major personality to take over the reins, one who would add prestige and fresh impetus to the society. In early 1818, they had a meeting with Ioannis Kapodistrias, who not only refused, but later wrote that he considered Filiki Eteria guilty for the havoc that was foreboded in Greece.

Alexandros Ypsilantis was contacted and asked to assume leadership of Filiki Eteria,[8] which he did in April 1820. He began active preparations for a revolt and with the setting up of a military unit for the purpose that he named the Sacred Band. Various proposals were made for the location regarding the break out of the revolution. One of them was the to be started in Constantinople, the heart of the empire, that was the long-term target of the revolutionaries. Finally the decision that was taken was to start from the Peloponnese (Morea), and the Danubian Principalities at the same time. The society especially wanted also to take advantage of the involvement of significant Ottoman forces, including the pasha of the Moreas, against Ali Pasha of Ioannina.

See also

References

- 1 2 Alison, Phillips W. (1897). The war of Greek independence, 1821 to 1833. London : Smith, Elder. pp. 20, 21. (retrieved from University of California Library)

- ↑ Filiki Eteria: The Diaspora Secret Society That Sparked Greek Independence

- ↑ Clogg, Richard (1976), "'Social Banditry': The Memoirs of Theodoros Kolokotronis", The Movement for Greek Independence 1770–1821, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 166–174, ISBN 9781349028474, retrieved 2018-07-19

- ↑ "Laskarina Bouboulina", Wikipedia, 2018-06-22, retrieved 2018-07-19

- ↑ Greek War of Independence. A Dictionary of World History. 2000. retrieved 9 May. 2009 Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ John S. Koliopoulos, Brigands with a Cause - Brigandage and Irredentism in Modern Greece 1821-1912, Clarendon Press Oxford (1987), p. 41.

- 1 2 Michaletos, Ioannis (2006-09-28). "Freemasonry in Greece: Secret History Revealed". Balkanalysis.com. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- 1 2 Berend, Tibor Iván (2003). History derailed. University of California Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-520-23299-0.

- 1 2 Cunningham, Allan; Ingram, Edward (1993). Anglo-Ottoman encounters in the age of revolution. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-7146-3494-4.

ISBN 0-7146-3494-8

- ↑ Wintle, Michael (2008). Imagining Europe: Europe and European civilisation as seen from its margins and by the rest of the world, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Peter Lang. p. 112. ISBN 978-90-5201-431-9. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- 1 2 Waddington, George (1825). A visit to Greece, in 1823 and 1824. London: John Murray. p. xviii (28). Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Waddington, George (1825). A visit to Greece, in 1823 and 1824. London: John Murray. p. xx,xxi (20,21). Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- 1 2 Flessas, Constantinos (1842). History of the Holy Fight (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: P.A.Comnenos. pp. 44–45. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Filiki Etaireia. |

- Vournas, Tasos. Friendly Society: her illegal organisational and persecution by the foreigners, Tolides Bros, (Athens 1982).

- Metropolitan of Old Patras Germanos, Memoirs, (Introductory note, index, ref. Ioanna Yiannaropoulos – Tassos Gritsopoulos), (Athens 1975).

- Kordatos, Yannis. Rigas Feraios and Balkan Federation, (Athens 1974).

- Xanthos, Emmanuil. Memoirs for the Friendly Society, (facsimile reprint of 1834 ed), Vergina, (Athens 1996).

- Michaletos, Ioannis. The History of a Greek Secret Society: Structure and Rites of the Philiki Etaireia, (www.balkanalysis.com 2007).