Karamanlides

Karamanlidika inscription found on the door of a house in İncesu, Turkey | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Greece | |

| Languages | |

| Originally Karamanli Turkish, now predominantly Modern Greek | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity |

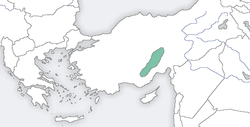

The Karamanlides (Greek: Καραμανλήδες; Turkish: Karamanlılar), or simply Karamanlis are a Greek-Orthodox, Turkish-speaking people native to the Karaman and Cappadocia regions of Anatolia. Today, a majority of the population live within Greece, though there is a notable diaspora in Western Europe and North America.

Etymology

Karamanlides were Greek-Orthodox Christians in Central Anatolia who spoke Turkish as their primary language. The term is geographical, derived from the 13th century Beylik of Karaman. This was the first Turkish kingdom to use Turkish as its official language and originally the term would only refer to the inhabitants of the town of Karaman or from the region of Karaman.

Language

Historically, the Karamanlides spoke Karamanli Turkish. Its vocabulary drew overwhelmingly from Turkic words with many Greek loan words. The language should not be confused with Cappadocian Greek, which was spoken in the same region during the same timeframe, but is derived from the Greek language. While the official Ottoman Turkish was written in the Arabic script, the Karamanlides used the Greek alphabet for writing its form of Turkish. Such texts are called Karamanlidika (Καραμανλήδικα / Καραμανλήδεια γραφή) or Karamanli Turkish today. Karamanli Turkish had its own literary tradition and produced numerous published works in print in the 19th century, some of them published by Evangelinos Misailidis, by the Anatoli or Misailidis publishing house (Misailidis 1986, p. 134).

Karamanli writers and speakers were expelled from Turkey as part of the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923. Some speakers preserved their language in the diaspora. The writing form stopped being used immediately after the Turkish state adopted the Latin alphabet.

A fragment of a manuscript written in Karamanli was also found in the Cairo Geniza.[1]

Origins

Academic disputes over the origins of the Karamanlides have led to the formation of two major theories.

According to one theory the Karamanlides descended from (religiously converted) Turkish soldiers (Turcopoles) that Byzantine emperors settled in Anatolia.[2]

According to another theory the Karamanlides are the direct descendants of Byzantine Greeks. Despite their adoption of the Turkish language, they maintained their Greek Orthodox faith.[2] Linguists were able to travel through Karamanli-speaking regions of Cappadocia and document the few remaining Greek words that mostly elderly residents could remember.[3]

According to another theory held by İbrahim Tatarlı, the Karamanlides descend from beyliks of Bulgar Turks shifting to another form of Turkic and preserving their Christian religion.[4] A similar theory of Necib Asım holds that Karamanlides descend from beyliks of Orthodox Bulgarians who shifted from Slavic to Turkish.[5][6] Those theories refer to some states (Anatolian beyliks and khanates), attested frequently as Bulgarian between 1098-1517 and seated in Ermenek, and the Bulgar Dagh mountains.[7] İbrahim Tatarlı claimed that those states consist of Christian Slavicized Bulgars, Turkic-speaking Bulgars, Kipchaks and Cumans from the Asen dynasty, but his claim is considered hypothetical and does not cite any relevant evidence of their Slavic-speaking characteristics.[8][9][10]

It seems that, although with notable exceptions, the Karamanlides did not manifest the Greek national identity of the time, preferring instead to call themselves Rum, "Romans" "Christians", or "Christians of Anatolia".[11] There were also prominent members of the community, such as Papa Eftim I, who believed that the Karamanlis originally were of Turkish descent.[12]

Many Karamanlides were forced to leave their homes during the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Early estimates placed the number of Orthodox Christians expelled from central and southern Anatolia at around 100,000.[13] However, the Karamanlides were numbered at around 400,000 at the time of the exchange.[14]

The former premier of Greece, named Karamanlis, has his roots in Karaman.

Culture

The distinct culture that developed among the Karamanlides blended elements of Orthodox Christianity with an Ottoman-Turkish flavor that characterized their willingness to accept and immerse themselves in foreign customs. From the 14th to the 19th centuries, they enjoyed an explosion in literary refinement. Karamanli authors were especially productive in philosophy, religious writings, novels, and historical texts. Lyrical poetry in the late 19th century describes their indifference to both Greek and Turkish governments, and the confusion they felt as a Turkish-speaking people with a Greek ethos.

References

- ↑ Julia Krivoruchko Karamanli – a new language variety in the Genizah: T-S AS 215.255 http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/Taylor-Schechter/fotm/july-2012/index.html

- 1 2 Vryonis, Speros. Studies on Byzantium, Seljuks, and Ottomans: Reprinted Studies. Undena Publications, 1981, ISBN 0-89003-071-5, p. 305. "The origins of the Karamanlides have long been disputed, there being two basic theories on the subject. According to one, they are the remnants of the Greek-speaking Byzantine population which, though it remained Orthodox, was linguistically Turkified. The second theory holds that they were originally Turkish soldiers which the Byzantine emperors had settled in Anatolia in large numbers and who retained their language and Christian religion after the Turkish conquests..."

- ↑ Dawkins, R.M. 1916. Modern Greek in Asia Minor. A study of dialect of Silly, Cappadocia and Pharasa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Tatarlı, İbrahim (2003). "YÜZYILLARDA BULGAR BOYLARI VE BEYLİKLERİ, ONLARIN ANADOLU SELÇUKLULARI İMPARATORLUĞU VE KARAMAN BEYLİĞİ İLE İLİŞKİLERİ". Bulgaristan'da Türk halk kültürü ve edebiyatının bazı ana sorunları, Türk varlığı. p. 88-102.

Belki de Türk dili kullanan, fakat dinleri Ortodoks hristiyanlık olan "Karamanlı" olarak nitelendirilen oymaklar da Türk Bulgarlarındandır.

- ↑ Asım, Necib, “Anadolu'da Bulgarlar,” İkdam, no. 8842 (25 Safar 1340/oct. 28, 1921), p.4

- ↑ Венедикова, Катерина (1998). Българите в Мала Азия: От древността до наши дни. University of Michigan. ISBN 9789548638128.

Особено ценни са бележките на Неджип Асъм във втората половина от статията за езика, религията и произхода на тези българи. Той отбелязва, че "може с основание да се мисли, че ортодоксите, които днес се намират по онези места (от Бейшехир до Коня, бел. К.В.) и говорят турски език, са остатъци, продължение от онези българи. Асъм подчертава нещо много важно, което не е писано от други изследвачи, нито пък става ясно от текста на "История на Караман", като изключим името на кралицата на българите от Бейшехир до Коня, Катерина, в приложението към разширения турски вариант на летописа, което говори за християнски произход: езикът на тези българи е славянски, а тяхната религия - християнска.

- ↑ Венедикова, Катерина (1998). Българите в Мала Азия: От древността до наши дни. University of Michigan. ISBN 9789548638128.

- ↑ Венедикова, Катерина Иванова (1998). Българите в Мала Азия: От древността до наши дни. University of Michigan. ISBN 9789548638128."Татарлъ допълва, че за българите разказват епически, литературни, летописни и документални извори (с.394). В Малоазииската българска държава били включени християнски славянизирани българи от Балканския полуостров, тюркоезични българи, къпчаци, кумани и др. За съжаление, авторът не навсякъде посочва източниците за сведенията, които дава, и за заключенията си (като например за град Булгар и за славянизираните българи) не е посочено откъде са данните."

- ↑ Венедикова, Катерина. Българи, арменци и караманци в Средновековна Мала Азия.

За произхода на българите в Южен Анадол са изказани предимно предположения, а категоричните твърдения за славянския език и християнската религия на тези българи в повечето случаи не се подкрепят от изследователите с позоваване на конкретен извор.

- ↑ Шишманов, Димитър (2001). Необикновената история на малоазийските българи (2 ed.). София: Пони. p. 13-18.

- ↑ Mackridge, Peter. Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766-1976, Oxford, 2009, ISBN 0-199-59905-X, p.65.

- ↑ "Anadolu'nun Ortodoks Topluluğu: Karamanlılar". beyaztarih.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ Blanchard, Raoul. "The Exchange of Populations Between Greece and Turkey." Geographical Review, 15.3 (1925): 449-56.

- ↑ Pavlowitch, Stevan K. A History of the Balkans, 1804-1945. Longman, 1999, ISBN 0-582-04585-1, p. 36. "The karamanlides were Turkish-speaking Greeks or Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians who lived mainly in Asia Minor. They numbered some 400,000 at the time of the 1923 exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey."