Dura, Hebron

| Dura | ||

|---|---|---|

| Other transcription(s) | ||

| • Arabic | دورا | |

| • Also spelled | Durrah (official) | |

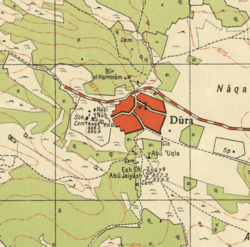

Map of Dura circa 1943 | ||

| ||

Dura Location of Dura within Palestine | ||

| Coordinates: 31°30′25″N 35°01′40″E / 31.50694°N 35.02778°ECoordinates: 31°30′25″N 35°01′40″E / 31.50694°N 35.02778°E | ||

| Palestine grid | 152/101 | |

| Governorate | Hebron | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | City (from 1967) | |

| • Head of Municipality | Dr. Sameer Hamid Al-Namoura | |

| Population (2015) | ||

| • Jurisdiction | 36,170 | |

| Name meaning | Dura (proper noun) from Hebrew אֲדוֹרַים Adoraim[1] | |

Dura (Arabic: دورا) is a Palestinian city located eleven kilometers southwest of Hebron in the Hebron Governorate in the southern West Bank. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the town had a population of over 28,268 in 2007.[2] The current mayor is Sameer Al-Namoura.

The city is identified with the biblical Adoraim, mentioned by Apocrypha and Josephus. The modern Arabic name is a sound conversion from Hebrew.

In 1517, the village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Syria. After the British Mandate, in the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Dura was occupied by Jordan and came under Jordanian rule. Dura was established as a municipality on January 1, 1967, five months before it was occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War.

Etymology

The present-day name of Dura has been identified with ancient Adoraim or the Adora of 1 Macc.13.20[3][4] Mentioned as Adora by Apocrypha and often by Josephus.[5] A weak letter is usually lost in Hebrew to Arabic sound conversion, such as in the case of Adoraim to Dura.[6] A loss of a first feeble letter is not uncommon and the form of Dora could be found as early as in several instances of Josephus writings.[5] The village was originally built on two hills: Dura al-‘Amaira and Dura al-Arjan possibly reflecting dual grammatical number of Adoraim name, which could also be a double village during antiquity.[7]

History

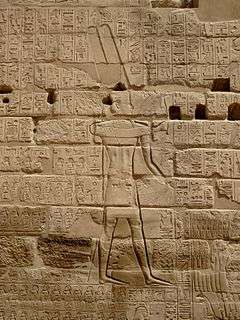

Dura is an ancient place, where old cisterns and fragments of mosaics have been found.[8] The settlement was mentioned in the Amarna letters as early as 14th century BC.,[7][9] in the Anastasi Papyrus[10] and in the Shoshenq tablets.[11][12] According to the biblical account, Adurim was fortified by Rehoboam (974 BC – 913 BC), King of the United Monarchy of Israel and later the King of the Kingdom of Judah, who was a son of Solomon and a grandson of David. Pharaoh Shoshenq conducted a military campaign into Canaan in 925 BC and lists the cities he conquered, number 19 in the list is associated with the biblical city of Judah. The Shoshenq's topographical list preserved in the main temple of Karnak provides "one of the strongest connections between the Bible and other ancient Near Eastern evidence".[13] In the early 6th century BC the Babylonians attacked the Kingdom of Judah, the southern part of the country, from Adoraim near Hebron to Maresha and beyond, fell to the Edom.[14][15] Following the Alexander the Great's conquest, the village population of the ancient Palestine preserved their traditional way of life, however Jewish urban centers such as Adoraim exhibited a degree of hellenization.[16] The settlement is mentioned in the Zenon Papyri in 259 BC as a "fortress city".[17] In Adora, Simon Maccabeus stopped the advancing Diodotus Tryphon army in 142 BC.[18] According to Josephus, John Hyrcanus captured the city after the death of Antiochus VII in 129 BC. The city inhabitants, who were alleged to have been of Esau's progeny (Idumeans), were forced to convert to Judaism during the reign of Hyrcanus, on the condition that they be allowed to remain in the country.[19] It may have been the administrative center of the district of eastern Idumaea established by the Roman consul Aulus Gabinius, though other possibilities have been suggested.[20] Mukaddasi, writing around 985 CE, noted that Palestine was famous for its vineyards and a type of raisin called Dūrī, said to be from Dura.[21] According to Guy Le Strange, the city locality is in the Vale of Mamre mentioned in the story of The Twelve Spies who brought back to Moses large grapes of Eshkol as recorded in the Book of Numbers.[22]

Ottoman period

In 1517, the village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Palestine. In 1596 it appeared in the tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Khalil of the Liwa of Quds. It had a population of 49 Muslim households. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 33,3% on agricultural products, including on wheat, barley, olives, vines or fruit trees, and goats or beehives; a total of 10,000 akçe.[23]

In 1834, Dura's inhabitants participated in an uprising against the Egyptian Ibrahim Pasha, who took over the area between 1831 and 1840. When Robinson visited in 1838, he described Dura as one of the largest villages in the area, and the residence of the Sheikhs of Ibn Omar, who had formerly ruled the area.[24]

In 1863 the French explorer Victor Guérin visited the place, and noted that "Fragments of ancient columns, and a good number of cut stones taken from old constructions and built up in the Arab houses, show the antiquity of the place. Two barracks especially have been built in this way. Above the door of one, a block forming the lintel was once ornamented with mouldings, now very much mutilated. Close to the town is a celebrated wely in which lies a colossal sarcophagus, containing, it is said, the body of Noah."[25]

An Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that Dura had a population of 420, in 144 houses, though the population count included men, only.[26][27] In 1877 Lieutenant Kitchener had some boys publicly flogged in Dura following an incident when stones were thrown at a member of the Palestine Exploration Fund survey party.[28]

In 1883, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Dura as "A large and nourishing village on the flat slope of a hill, with open ground on the east for about a mile. This plain is cultivated with corn. To the north of Dura are a few olives, and others on the south. The houses are of stone. South of the village are two Mukams with white domes; and on the west, higher than the village, is the tomb of Neby Nuh (Prophet Noah). Near these there are rock-cut sepulchres. The place is well supplied from three springs on the east and one on the south."[29]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Dura was divided into Dura al-‘Amaira, with 2,565 inhabitants, and Dura al-Arjan, with 3,269 inhabitants; a total of 5,834, all Muslims.[30] The report of the 1931 census wrote that "the village in the Hebron sub-district commonly known as Dura is a congeries of neighbouring localities each of which has a distinctive name; and, while Dura is a remarkable example of neighbourly agglutination, the phenomenon is not infrequent in other villages". The total of 70 locations listed in the report had 1538 inhabited houses and a population of 7255 Muslims.[31]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Dura was 9,700, all Muslims,[32] who owned 240,704 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[33] 3,917 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 90,637 for cereals,[34] while 226 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[35] Dura village lands covered in this period an estimated 240 sq. miles. [36]

Jordanian era

In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Dura came under Jordanian rule.

In 1961, the population of Dura was 3,852.[37]

The municipality of Dura was established on January 1, 1967, five months before it was occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War.

1967 War and its aftermath

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, Dura has been under Israeli occupation. The population in the 1967 census conducted by the Israeli authorities was 4,954.[38]

After the Palestinian National Authority was ceded control of the town in 1995, a local committee was set up to prevent land confiscation from the town and the municipal council was expanded. Many Palestinian ministries and governmental institutions opened offices in Dura, enhancing its role in Palestinian politics.

In June 2014, during the search to find three kidnapped boys, 150 Israeli soldiers stormed Dura's Haninia neighbourhood in a dawn raid to detain a person, and were met by young men and boys throwing rocks. An Israeli soldier shot and killed a teenager who was among the rock throwers, 13[39] or 15-year-old Mohammed Dudeen.[40][41][42]

Israeli settlement

The Israeli settlement of Adora, Har Hebron is located 4 kilometers north of the town in the Judean Mountains[43] and has 440 inhabitants.[44] The international community considers Israeli settlements in the West Bank illegal under international law, but the Israeli government disputes this.[45] The settlement community falls under the jurisdiction of Har Hebron Regional Council.[46]

Climate

The climate of Dura is dry in the summers and experiences moderate precipitation during winter. Average annual precipitation depend on specific geographic locations within the town. The area of Dahr Alhadaba receives an annual average of 400–600 mm of rain, southern slopes 300–400 mm and the northern region of the Dura hills 250–300.

Sites of interest

A local Palestinian legend has it that the patriarch Noah, in Islamic tradition Nebi Nûh, was buried in Dura,[47] and a shrine there commemorates this Arab tradition.[48]

See also

References

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 393

- ↑ 2007 PCBS Census Archived December 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. p.119.

- ↑ B. Bar-Kochva, Judas Maccabaeus: The Jewish Struggle Against the Seleucids, Cambridge University Press, 2002 p.285.

- ↑ James L. Kugel, A Walk Through Jubilees: Studies in the Book of Jubilees and the World of Its Creation, BRILL, 2012 p.303,

- 1 2 Edward ROBINSON (1841). Biblical researches in Palestine, mount Sinai and Arabia Petrea. J.Murray. p. 4.

- ↑ Conder, CR (1876). "Notes on the Language of the Native Peasantry in Palestine" (PDF). Palestine Exploration Quarterly (Taylor & Francis). Retrieved Mar 25, 2018.

- 1 2 Moshe Sharon (13 December 2013). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Volume Five: H-I. BRILL. p. 86. ISBN 978-90-04-25481-7.

- ↑ Dauphin, 1998, p. 946

- ↑ Gaston Maspero (1896). History of the Ancient Peoples of the Classic East. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 131.

- ↑ Heinrich Karl Brugsch (1858). Geographische Inschriften altägyptischer Denkmäler. p. 49.

- ↑ Zeitschrift für ägyptische sprache und altertumskunde. 1880. p. 46.

- ↑ Na'aman, Nadav. "Arad in the Topographical List of Shishak." Tel Aviv 12, no. 1 (1985): 91-92.

- ↑ Junkkaala, Eero. "Three conquests of Canaan: a comparative study of two Egyptian military campaigns and Joshua 10-12 in the light of recent archaeological evidence." (2006).

- ↑ Lindsay, John. "The Babylonian kings and Edom, 605–550 BC." Palestine Exploration Quarterly 108, no. 1 (1976): 23-39.

- ↑ Albright, William F. "Ostracon No. 6043 from Ezion-Geber." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 82 (1941): 11-15.

- ↑ Lee I. Levine (1 March 2012). Judaism and Hellenism in Antiquity: Conflict or Confluence?. University of Washington Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-295-80382-1.

- ↑ M. Gabrieli; Isaac Sachs (1969). Tour Israel: a tour guide of the country. Evyatar Pub. House; distributed by Steimatzky. p. 99.

- ↑ Kraeling, Emil G. "Two Place Names of Hellenistic Palestine." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 7, no. 3 (1948): 199-201.

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities (Book xiii, chapter ix, verse 1).

- ↑ Avi-Yonah, 1977, pp. 83–84

- ↑ Mukaddasi, Description of Syria - Including Palestine, London 1886, p. 69 (note 3).

- ↑ Mukaddasi, 1895, p. 69

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 124

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, pp. 2-5

- ↑ Guérin, 1869, pp. 353 −355; as translated by Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 328

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 153

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 142, noted 249 houses

- ↑ Kitchener, 1878, p. 14

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 304

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Hebron, p. 10

- ↑ Mills, 1932, pp. Preface, 28–32

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 23

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 50

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 93

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 143

- ↑ Magen Broshi, 'The Population of Western Palestine in the Roman-Byzantine Period,' Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 236 (Autumn, 1979), pp.1-10, p.6.

- ↑ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 13

- ↑ Perlmann, Joel (November 2011 – February 2012). "The 1967 Census of the West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Digitized Version" (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ '13-year-old Palestinian shot dead by Israeli forces in Dura,' Ma'an News Agency, 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Jodi Rudoren, 'Israeli Troops Kill Palestinian Teenager Protesting West Bank Arrests,' The New York Times, 20 June 2014:'as he and other youths hurled rocks at about 150 soldiers.'"One of them crouched and opened fire on the boy," said Bassam al-Awadeh, 42, who said he watched from about 150 yards (140 m) away. "The boy was hit in his heart and his abdomen.".'

- ↑ "14-year-old Palestinian shot dead by Israeli forces in Dura". Maannews.net. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Palestinian killed in students hunt". Irish Independent. AP. 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Hoberman, Haggai (2008). Keneged Kol HaSikuim [Against All Odds] (in Hebrew) (1st ed.). Sifriat Netzaim.

- ↑ "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ "The Geneva Convention". BBC News. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ https://www.hrhevron.co.il Har Hebron Regional Council Official Website

- ↑ Edward Platt, City of Abraham: History, Myth and Memory: A Journey through Hebron, Pan Macmillan, 2012 p.54.

- ↑ Edward Robinson,Biblical researches in Palestine and the adjacent regions: a journal of travels in the years 1838 and 1852, 2nd ed. J Murray 1856 p,214

Bibliography

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1977). The Holy Land: a historical geography from the Persian to the Arab conquest (536 B.C. to A.D. 640). Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Berrett, L.M.C. (1996). Discovering the World of the Bible. Grandin Book Company. p. 196. ISBN 9780910523523. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Kitchener, H.H. (1878). "Lieut Kitchener`s reports". Quarterly statement – Palestine Exploration Fund. 10: 10–15. doi:10.1179/peq.1878.10.1.10.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Mukaddasi (1895). Description of Syria, including Palestine. Translator: Guy le Strange. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To The City of Dura

- Dura, Welcome to Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 21: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Dura Town (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- Dura Town Profile, ARIJ

- Dura Area Photo, ARIJ

- The priorities and needs for development in Dura town based on the community and local authorities' assessment, ARIJ

- 1946 survey with detailed plans.