Bronchitis

| Bronchitis | |

|---|---|

| |

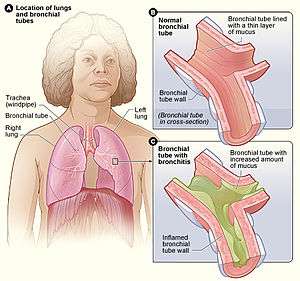

| Figure A shows the location of the lungs and bronchial tubes. Figure B is an enlarged view of a normal bronchial tube. Figure C is an enlarged view of a bronchial tube with bronchitis. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease, pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Coughing up mucus, wheezing, shortness of breath, chest discomfort[1] |

| Types | Acute, chronic[1] |

| Frequency |

Acute: ~5% of people a year[2][3] Chronic: ~5% of people[3] |

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs.[1] Symptoms include coughing up mucus, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest discomfort.[1] Bronchitis is divided into two types: acute and chronic.[1] Acute bronchitis is also known as a chest cold.[1]

Acute bronchitis usually has a cough that lasts around three weeks.[4] In more than 90% of cases the cause is a viral infection.[4] These viruses may be spread through the air when people cough or by direct contact.[1] Risk factors include exposure to tobacco smoke, dust, and other air pollution.[1] A small number of cases are due to high levels of air pollution or bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Bordetella pertussis.[4][5] Treatment of acute bronchitis typically involves rest, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and NSAIDs to help with the fever.[6][7]

Chronic bronchitis is defined as a productive cough that lasts for three months or more per year for at least two years.[8] Most people with chronic bronchitis have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[9] Tobacco smoking is the most common cause, with a number of other factors such as air pollution and genetics playing a smaller role.[10] Treatments include quitting smoking, vaccinations, rehabilitation, and often inhaled bronchodilators and steroids.[11] Some people may benefit from long-term oxygen therapy or lung transplantation.[11]

Acute bronchitis is one of the most common diseases.[6][12] About 5% of adults are affected and about 6% of children have at least one episode a year.[2][13] In 2010, COPD affects 329 million people or nearly 5% of the global population.[3] In 2013, it resulted in 2.9 million deaths, a change from 2.4 million deaths in 1990.[14]

Acute bronchitis

Acute bronchitis, also known as a chest cold, is short term inflammation of the bronchi of the lungs.[1][4] The most common symptom is a cough.[4] Other symptoms include coughing up mucus, wheezing, shortness of breath, fever, and chest discomfort. The infection may last from a few to ten days.[1] The cough may persist for several weeks afterwards, with the total duration of symptoms usually around three weeks.[1][4] Some have symptoms for up to six weeks.[6]

Cause

In more than 90% of cases, the cause is a viral infection.[4] These viruses may spread through the air when people cough or by direct contact. Risk factors include exposure to tobacco smoke, dust, and other air pollution.[1] A small number of cases are due to high levels of air pollution or bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Bordetella pertussis.[4][5]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically based on a person's signs and symptoms.[15] The color of the sputum does not indicate if the infection is viral or bacterial. Determining the underlying organism is usually not required.[4] Other causes of similar symptoms include asthma, pneumonia, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, and COPD.[4][2] A chest X-ray may be useful to detect pneumonia.[4]

Another common sign of bronchitis is a cough which lasts ten days to three weeks. If the cough lasts a month or a year, it may become chronic bronchitis. In addition, a fever may be present. Acute bronchitis is normally caused by a viral infection. Typically, these infections are rhinovirus, parainfluenza, or influenza. No specific testing is normally needed in order to diagnose acute bronchitis.[16]

Treatment

Prevention is by not smoking and avoiding other lung irritants. Frequent hand washing may also be protective.[17] Treatment for acute bronchitis usually involves rest, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and NSAIDs to help with the fever.[6][7] Cough medicine has little support for its use, and it is not recommended in children who are less than six years of age.[4][18] There is tentative evidence that salbutamol may be useful in people with wheezing; however, it may result in nervousness and tremors.[4][19] Antibiotics should generally not be used.[20] An exception is when acute bronchitis is due to pertussis. Tentative evidence supports honey and pelargonium to help with symptoms.[4] Getting plenty of rest and drinking enough fluids are often recommended as well.[21]

Epidemiology

Acute bronchitis is one of the most-common diseases.[6][12] About 5% of adults are affected, and about 6% of children have at least one episode a year.[2][13] It occurs more often in the winter.[2] More than 10 million people in the US visit a doctor each year for this condition, with about 70% receiving antibiotics which are mostly not needed.[6] There are efforts to decrease the use of antibiotics in acute bronchitis.[12]

Chronic bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is defined as a productive cough that lasts for three months or more per year for at least two years.[8] Most people with chronic bronchitis also have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[9] Protracted bacterial bronchitis is defined as a chronic productive cough with a positive bronchoalveolar lavage that resolves with antibiotics.[22][23] Symptoms of chronic bronchitis may include wheezing and shortness of breath, especially upon exertion and low oxygen saturations.[24] The cough is often worse soon after awakening, and the sputum produced may have a yellow or green color and may be streaked with specks of blood.[25]

Cause

Most cases of chronic bronchitis are caused by smoking and other forms of tobacco.[24][26][27] In addition, chronic inhalation of air pollution or irritating fumes or dust from hazardous exposures in occupations such as coal mining, grain handling, textile manufacturing, livestock farming,[28] and metal moulding may also be a risk factor for the development of chronic bronchitis.[29][30][31] Protracted bacterial bronchitis is usually caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Non-typable Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis.[22][23]

Diagnosis

Individuals with obstructive pulmonary disorders such as bronchitis may present with a decreased FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio on pulmonary function tests.[32][33][34] Unlike other common obstructive disorders such as asthma or emphysema, bronchitis rarely causes a high residual volume (the volume of air remaining in the lungs after a maximal exhalation effort).[35]

Treatment

Evidence suggests that the decline in lung function observed in chronic bronchitis may be slowed with smoking cessation.[36] Chronic bronchitis is treated symptomatically and may be treated in a nonpharmacologic manner or with pharmacologic therapeutic agents. Typical nonpharmacologic approaches to the management of COPD including bronchitis may include pulmonary rehabilitation, lung volume reduction surgery, and lung transplantation.[36] Inflammation and edema of the respiratory epithelium may be reduced with inhaled corticosteroids.[37] Wheezing and shortness of breath can be treated by reducing bronchospasm (reversible narrowing of smaller bronchi due to constriction of the smooth muscle) with bronchodilators such as inhaled long acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonists (e.g., salmeterol) and inhaled anticholinergics such as ipratropium bromide or tiotropium bromide.[38] Mucolytics may have a small therapeutic effect on acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.[39] Supplemental oxygen is used to treat hypoxemia (too little oxygen in the blood), and it has been shown to reduce mortality in people with chronic bronchitis.[25][36] Oxygen supplementation can cause decreased respiratory drive, resulting in increased blood levels of carbon dioxide (hypercapnia) and subsequent respiratory acidosis.[40] Protracted bacterial bronchitis (lasting more than 4 weeks) in children may be helped by antibiotics.[41]

Epidemiology

Chronic bronchitis has a 3.4% to 22% prevalence rate among the general population. Individuals over age 45 years of age, smokers, those that live in areas with high air pollution, and anybody with asthma all have a higher risk of developing chronic bronchitis.[42] This wide range is due to the different definitions of chronic bronchitis that can be diagnosed based on signs and symptoms or the clinical diagnosis of the disorder. Chronic bronchitis tends to affect men more often than women. While the primary risk factor for chronic bronchitis is smoking, there is still a 4%-22% chance that never smokers can get chronic bronchitis. This might suggest other risk factors such as the inhalation of fuels, dusts, and fumes.[43] Obesity has also been linked to an increased risk for chronic bronchitis. In the United States in the year 2014, per 100,000 population the death rate of chronic bronchitis was 0.2.[44]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "What Is Bronchitis?". August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wenzel, RP; Fowler AA, 3rd (16 November 2006). "Clinical practice. Acute bronchitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (20): 2125–30. doi:10.1056/nejmcp061493. PMID 17108344.

- 1 2 3 Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Albert, RH (1 December 2010). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis". American Family Physician. 82 (11): 1345–50. PMID 21121518.

- 1 2 "What Causes Bronchitis?". August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tackett, KL; Atkins, A (December 2012). "Evidence-based acute bronchitis therapy". Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 25 (6): 586–90. doi:10.1177/0897190012460826. PMID 23076965.

- 1 2 "How Is Bronchitis Treated?". August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Diagnosis and Assessment" (PDF). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. pp. 9–17.

- 1 2 Reilly, John J.; Silverman, Edwin K.; Shapiro, Steven D. (2011). "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". In Longo, Dan; Fauci, Anthony; Kasper, Dennis; Hauser, Stephen; Jameson, J.; Loscalzo, Joseph. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 2151–9. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ↑ Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M (April 2012). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Lancet. 379 (9823): 1341–51. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1000.1967. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. PMID 22314182.

- 1 2 Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, Zielinski J (September 2007). "Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176 (6): 532–55. doi:10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. PMID 17507545.

- 1 2 3 Braman, SS (January 2006). "Chronic cough due to acute bronchitis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines". Chest. 129 (1 Suppl): 95S–103S. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.95S. PMID 16428698.

- 1 2 Fleming, DM; Elliot, AJ (March 2007). "The management of acute bronchitis in children". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (4): 415–26. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.4.415. PMID 17309336.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "How Is Bronchitis Diagnosed?". August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Acute Bronchitis - Pulmonary Disorders - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ↑ "How Can Bronchitis Be Prevented?". August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Smith, SM; Schroeder, K; Fahey, T (24 November 2014). "Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD001831. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub5. PMID 25420096.

- ↑ Becker, Lorne A.; Hom, Jeffrey; Villasis-Keever, Miguel; van der Wouden, Johannes C. (2015-09-03). "Beta2-agonists for acute cough or a clinical diagnosis of acute bronchitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD001726. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001726.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 26333656.

- ↑ Smith, Susan M.; Fahey, Tom; Smucny, John; Becker, Lorne A. (2017). "Antibiotics for acute bronchitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD000245. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000245.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 28626858.

- ↑ "Acute Bronchitis | Bronchitis Symptoms | MedlinePlus". Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- 1 2 Goldsobel, AB; Chipps, BE (March 2010). "Cough in the pediatric population". The Journal of Pediatrics. 156 (3): 352–358.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.004. PMID 20176183.

- 1 2 Craven, V; Everard, ML (January 2013). "Protracted bacterial bronchitis: reinventing an old disease". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 98 (1): 72–76. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-302760. PMID 23175647.

- 1 2 U.S. National Library of Medicine (2011). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- 1 2 Cohen, Jonathan; Powderly, William (2004). Infectious Diseases, 2nd ed. Mosby (Elsevier). Chapter 33: Bronchitis, Bronchiectasis, and Cystic Fibrosis. ISBN 978-0323025737.

- ↑ "Understanding Chronic Bronchitis". American Lung Association. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ Forey, BA; Thornton, AJ; Lee, PN (June 2011). "Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating smoking to COPD, chronic bronchitis and emphysema". BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 11 (36): 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-11-36. PMC 3128042. PMID 21672193.

- ↑ Szczyrek, M; Krawczyk, P; Milanowski, J; Jastrzebska, I; Zwolak, A; Daniluk, J (2011). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in farmers and agricultural workers-an overview". Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 18 (2): 310–313. PMID 22216804.

- ↑ Fischer, BM; Pavlisko, E; Voynow, JA (2011). "Pathogenic triad in COPD: oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and inflammation". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 6: 413–421. doi:10.2147/COPD.S10770. PMC 3157944. PMID 21857781.

- ↑ National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (2009). "Who Is at Risk for Bronchitis?". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (2012). "Respiratory Diseases Input: Occupational Risks". NIOSH Program Portfolio. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Respiratory Health Spirometry Procedures Manual" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Willemse, BW; Postma, DS; Timens, W; ten Hacken, NH (March 2004). "The impact of smoking cessation on respiratory symptoms, lung function, airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation". The European Respiratory Journal. 23 (3): 464–476. doi:10.1183/09031936.04.00012704. PMID 15065840.

- ↑ Mohamed Hoesein, FA; Zanen, P; Lammers, JW (June 2011). "Lower limit of normal or FEV1/FVC<0.70 in diagnosing COPD: an evidence-based review". Respiratory Medicine. 105 (6): 907–915. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.008. PMID 21295958.

- ↑ Wanger, J; Clausen, JL; Coates, A; Pedersen, OF; Brusasco, V; Burgos, F; Casaburi, R; Crapo, R; et al. (September 2005). "Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes". The European Respiratory Journal. 26 (3): 511–522. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. PMID 16135736.

- 1 2 3 Fauci, Anthony S.; Daniel L. Kasper; Dan L. Longo; Eugene Braunwald; Stephen L. Hauser; J. Larry Jameson (2008). Chapter 254. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147691-1.

- ↑ Spencer, S; Karner, C; Cates, CJ; Evans, DJ (2011). "Inhaled corticosteroids versus long acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (CD007033): CD007033. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007033.pub3. PMID 22161409.

- ↑ Karner, C; Chong, J; Poole, P (21 July 2014). "Tiotropium versus placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD009285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009285.pub3. PMID 25046211.

- ↑ Poole, Phillippa; Chong, Jimmy; Cates, Christopher J. (2015-07-29). "Mucolytic agents versus placebo for chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD001287. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001287.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 26222376.

- ↑ Iscoe, S; Beasley, R; Fisher, JA (2011). "Supplementary oxygen for nonhypoxemic patients:O2 much of a good thing?". Critical Care. 15 (3): 305. doi:10.1186/cc10229. PMC 3218982. PMID 21722334.

- ↑ Marchant, JM; Petsky, HL; Morris, PS; Chang, AB (31 July 2018). "Antibiotics for prolonged wet cough in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD004822. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004822.pub3. PMID 30062732.

- ↑ Kochanek, Kenneth (June 2016). "Deaths: Final Data for 2014". National Vital Statistics Reports. 65 (4).

- ↑ Kim, Victor; Criner, Gerard J. (2013-02-01). "Chronic Bronchitis and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 187 (3): 228–237. doi:10.1164/rccm.201210-1843CI. ISSN 1073-449X. PMC 4951627. PMID 23204254.

- ↑ Kochanek, Kenneth (June 2016). "Deaths: Final Data for 2014" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. 65 (4).

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- NIH entry on Bronchitis

- MedlinePlus entries on Acute bronchitis and Chronic bronchitis

- Mayo Clinic factsheet on bronchitis