Bronchiectasis

| Bronchiectasis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Figure A shows a cross-section of the lungs with normal airways and widened airways. Figure B shows a cross-section of a normal airway. Figure C shows a cross-section of an airway with bronchiectasis. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Productive cough, shortness of breath, chest pain[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Gradual[3] |

| Duration | Long term[4] |

| Causes | Infections, cystic fibrosis, unknown[2][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, CT scan[6] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, bronchodilators, lung transplant[2][7][8] |

| Frequency | 1–250 per 250,000 adults[9] |

Bronchiectasis is a disease in which there is permanent enlargement of parts of the airways of the lung.[4] Symptoms typically include a chronic cough with mucus production.[2] Other symptoms include shortness of breath, coughing up blood, and chest pain.[1] Wheezing and nail clubbing may also occur.[1] Those with the disease often get frequent lung infections.[7]

Bronchiectasis may result from a number of infective and acquired causes, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, immune system problems, as well the genetic disorder cystic fibrosis.[2][5] Cystic fibrosis eventually results in severe bronchiectasis in nearly all cases.[10] The cause in 10–50% of those without cystic fibrosis is unknown.[2] The mechanism of disease is breakdown of the airways due to an excessive inflammatory response.[2] Involved airways (bronchi) become enlarged and thus less able to clear secretions.[2] These secretions increase the amount of bacteria in the lungs, result in airway blockage and further breakdown of the airways.[2] It is classified as an obstructive lung disease, along with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.[11] The diagnosis is suspected based on a person's symptoms and confirmed using computed tomography.[6] Cultures of the mucus produced may be useful to determine treatment in those who have acute worsening and at least once a year.[6]

Worsening may occur due to infection and in these cases antibiotics are recommended.[7] Typical antibiotics used include amoxicillin, erythromycin, or doxycycline.[12] Antibiotics may also be used to prevent worsening of disease.[2] Airway clearance techniques, a type of physical therapy, are recommended.[13] Medications to dilate the airways may be useful in some but the evidence is not very good.[2] The use of inhaled steroids has not been found to be useful.[14] Surgery, while commonly done, has not been well studied.[15] Lung transplantation may be an option in those with very severe disease.[8] While the disease may cause significant health problems[2] most people with the disease do well.[4]

The disease affects between 1 per 1000 and 1 per 250,000 adults.[9] The disease is more common in women and increases as people age.[2] It became less common since the 1950s with the introduction of antibiotics.[9] It is more common among certain ethnic groups such as indigenous people.[9] It was first described by Rene Laennec in 1819.[2] The economic costs in the United States are estimated at $630 million per year.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Some people with bronchiectasis may have a cough productive of frequent green/yellow mucus (sputum), up to 240 ml (8 oz) daily. Bronchiectasis may also present with coughing up blood (hemoptysis) in the absence of sputum, called "dry bronchiectasis". Sputum production may also occur without coloration. People with bronchiectasis may have bad breath indicative of active infection. Frequent bronchial infections and breathlessness are two possible indicators of bronchiectasis.[5]

Crepitations and expiratory rhonchi may be heard on auscultation. Nail clubbing is rare.[16]

Causes

Bronchiectasis has both congenital and acquired causes, with the latter more frequent.[17] Cystic fibrosis is a cause in up to half of cases.[2] The cause in 10–50% of those without cystic fibrosis is unknown;[2] bronchiectasis without CF is known as non-CF bronchiectasis (NCBE).

Acquired causes

Tuberculosis, pneumonia, inhaled foreign bodies, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and bronchial tumours are the major acquired causes of bronchiectasis.[5][18] Infective causes associated with bronchiectasis include infections caused by the Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, or Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough and nontuberculous mycobacteria.[17][19]

Aspiration of ammonia and other toxic gases, pulmonary aspiration, alcoholism, heroin (drug use), various allergies all appear to be linked to the development of bronchiectasis.[20]

Various immunological and lifestyle factors have also been linked to the development of bronchiectasis:

- Childhood Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which predisposes patients to a variety of pulmonary ailments, such as pneumonia and other opportunistic infections.[21]

- Inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis. It can occur in Crohn's disease as well, but does so less frequently. Bronchiectasis in this situation usually stems from various allergic responses to inhaled fungal spores.[22] A Hiatal hernia can cause Bronchiectasis when the stomach acid that is aspirated into the lungs causes tissue damage.

- People with rheumatoid arthritis who smoke appear to have a tenfold increased rate of the disease.[23] Still, it is unclear as to whether or not cigarette smoke is a specific primary cause of bronchiectasis.

- Case reports of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and bronchiectasis occurring in the same persons have been published.[24]

No cause is identified in up to 50% of non-cystic-fibrosis related bronchiectasis.[16]

Congenital causes

Bronchiectasis may result from congenital disorders that affect cilia motility or ion transport.[5] Kartagener syndrome is one such disorder of cilia motility linked to the development of bronchiectasis.[25] A common cause is cystic fibrosis, which affects chloride ion transport, in which a small number of patients develop severe bronchiectasis.[26] Young's syndrome, which is clinically similar to cystic fibrosis, is thought to significantly contribute to the development of bronchiectasis. This is due to the occurrence of chronic infections of the sinuses and bronchiole tree.[27]

Other less-common congenital causes include primary immunodeficiencies, due to the weakened or nonexistent immune system response to severe, recurrent infections that commonly affect the lung.[28] Several other congenital disorders can also lead to bronchiectasis, including Williams-Campbell syndrome[29] and Marfan syndrome.[30]

People with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency have been found to be particularly susceptible to bronchiectasis, due to the loss of inhibition to enzyme elastase which cleaves elastin. This decreases the ability of the alveoli to return to normal shape during expiration.[31]

Pathophysiology

Bronchiectasis is a result of chronic inflammation compounded by an inability to clear mucoid secretions. This can be a result of genetic conditions resulting in a failure to clear sputum (primary ciliary dyskinesia), or resulting in more viscous sputum (cystic fibrosis), or the result of chronic or severe infections. Inflammation results in progressive destruction of the normal lung architecture, in particular, the elastic fibers of bronchi.[5]

Endobronchial tuberculosis commonly leads to bronchiectasis, either from bronchial stenosis or secondary traction from fibrosis.[32] Traction bronchiectasis characteristically affects peripheral bronchi (which lack cartilage support) in areas of end-stage fibrosis.[33]

Diagnosis

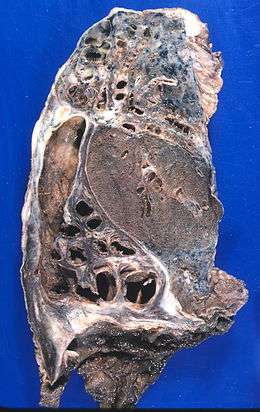

.jpg)

Bronchiectasis may be diagnosed clinically or on review of imaging.[5][34] The British Thoracic Society recommends all non-cystic-fibrosis-related bronchiectasis be confirmed by CT scan.[16] CT may reveal tree-in-bud abnormalities, dilated bronchi, and cysts with defined borders.[5]

Other investigations typically performed at diagnosis include blood tests, sputum cultures, and sometimes tests for specific genetic disorders.[5]

Prevention

In order to prevent bronchiectasis, children should be immunized against measles, pertussis, pneumonia, and other acute respiratory infections of childhood. While smoking has not been found to be a direct cause of bronchiectasis, it is certainly an irritant that all patients should avoid in order to prevent the development of infections (such as bronchitis) and further complications.[35]

Treatments to slow down the progression of this chronic disease include keeping bronchial airways clear and secretions weakened through various forms of pneumotherapy. Aggressively treating bronchial infections with antibiotics to prevent the destructive cycle of infection, damage to bronchial tubes, and more infection is also standard treatment. Regular vaccination against pneumonia, influenza and pertussis are generally advised. A healthy body mass index and regular doctor visits may have beneficial effects on the prevention of progressing bronchiectasis. The presence of hypoxemia, hypercapnia, dyspnea level and radiographic extent can greatly affect the mortality rate from this disease.[36]

Treatment

Treatment of bronchiectasis includes controlling infections and bronchial secretions, relieving airway obstructions, removal of affected portions of lung by surgical removal or artery embolization and preventing complications.[37] The prolonged use of antibiotics prevents detrimental infections and decreases hospitalizations in people with bronchiectasis,[38] but also increases the risk of people becoming infected with drug-resistant bacteria.[38]

Other treatment options include eliminating accumulated fluid with postural drainage and chest physiotherapy. Postural drainage techniques, aided by physiotherapists and respiratory therapists, are an important mainstay of treatment.[5][16] Airway clearance techniques appear useful.[13]

Surgery may also be used to treat localized bronchiectasis, removing obstructions that could cause progression of the disease.[39]

Inhaled steroid therapy that is consistently adhered to can reduce sputum production and decrease airway constriction over a period of time, and help prevent progression of bronchiectasis. This is not recommended for routine use in children.[16] One commonly used therapy is beclometasone dipropionate.[40] Although not approved for use in any country, mannitol dry inhalation powder, has been granted orphan drug status by the FDA for use in people with bronchiectasis and with cystic fibrosis.[41]

Epidemiology

The disease affects between 1 per 1000 and 1 per 250,000 adults.[9] The disease is more common in women and increases as people age.[2] It became less common since the 1950s, with the introduction of antibiotics. It is more common among certain ethnic groups such as indigenous people.[9]

The exact rates of bronchiectasis are often unclear as the symptoms are variable.[42] Rates of disease appeared to have increased in the United States between 2000 and 2007.[43]

History

René Laennec, the man who invented the stethoscope, used his invention to first discover bronchiectasis in 1819.[44] The disease was researched in greater detail by Sir William Osler in the late 1800s; it is suspected that Osler actually died of complications from undiagnosed bronchiectasis.[45]

Bronchiectasis comes from the Greek words "bronckos" (airway) and "ektasis" (widening).

References

- 1 2 3 "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Bronchiectasis?". NHLBI. June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 McShane, PJ; Naureckas, ET; Tino, G; Strek, ME (Sep 15, 2013). "Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 188 (6): 647–56. doi:10.1164/rccm.201303-0411CI. PMID 23898922.

- ↑ Maguire, G (November 2012). "Bronchiectasis – a guide for primary care". Australian family physician. 41 (11): 842–50. PMID 23145413.

- 1 2 3 "What Is Bronchiectasis?". NHLBI. June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Nicki R. Colledge; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. illustrated by Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- 1 2 3 "Quality Standards for Clinically Significant Bronchiectasis in Adults". British Thoracic Society. July 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "How Is Bronchiectasis Treated?". NHLBI. June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- 1 2 Corris, PA (Jun 2013). "Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis". Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 34 (3): 297–304. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1348469. PMID 23821505.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cottin, Vincent; Cordier, Jean-Francois; Richeldi, Luca (2015). Orphan Lung Diseases: A Clinical Guide to Rare Lung Disease. Springer. p. 30. ISBN 9781447124016. Archived from the original on 2016-08-21.

- ↑ Brant, William E.; Helms, Clyde A., eds. (2006). Fundamentals of diagnostic radiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 518. ISBN 9780781761352. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Michael Filbin; Lisa M. Lee; Shaffer, Brian L. (2003). Blueprints pathophysiology II : pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and rheumatology : notes & cases (1st ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. p. 12. ISBN 9781405103510. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Brent, Andrew; Davidson, Robert; Seale, Anna (2014). Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. OUP Oxford. p. 223. ISBN 9780191503078. Archived from the original on 2016-08-21.

- 1 2 Lee, AL; Burge, AT; Holland, AE (23 November 2015). "Airway clearance techniques for bronchiectasis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD008351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008351.pub3. PMID 26591003.

- ↑ Kapur, N; Bell, S; Kolbe, J; Chang, AB (Jan 21, 2009). "Inhaled steroids for bronchiectasis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000996. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000996.pub2. PMID 19160186.

- ↑ Corless, JA; Warburton, CJ (2000). "Surgery vs non-surgical treatment for bronchiectasis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD002180. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002180. PMID 11034745.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hill, Adam T; Pasteur, Mark; Cornford, Charles; Welham, Sally; Bilton, Diana (1 January 2011). "Primary care summary of the British Thoracic Society Guideline on the management of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis". Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 20 (2): 135–40. doi:10.4104/pcrj.2011.00007. PMID 21336465.

- 1 2 Hassan, Isaac (8 December 2006). "Bronchiectasis". eMedicine Specialties Encyclopedia. Gibraltar: WebMD. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ↑ Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

- ↑ Fowler, S. J.; French, J.; Screaton, N.J.; Foweraker, A.; Condliffe, A.; Haworth, C.S:; Exley, A.R.; Bilton, D. (2006). "Nontuberculous mycobacteria in bronchiectasis: prevalence and patient characteristics". European Respiratory Journal. 28 (5): 1204–1210. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00149805.

- ↑ Lamari NM, Martins AL, Oliveira JV, Marino LC, Valério N (2006). "Bronchiectasis and clearence [sic] physiotherapy: emphasis in postural drainage and percussion". Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (in Portuguese). 21 (2). doi:10.1590/S1678-97412006000200015.

- ↑ Sheikh S, Madiraju K, Steiner P, Rao M (1997). "Bronchiectasis in pediatric AIDS". Chest. 112 (5): 1202–7. doi:10.1378/chest.112.5.1202. PMID 9367458.

- ↑ Ferguson HR, Convery RP (2002). "An unusual complication of ulcerative colitis". Postgrad. Med. J. 78 (922): 503. doi:10.1136/pmj.78.922.503. PMC 1742448. PMID 12185236.

- ↑ Kaushik, VV; Hutchinson D; Desmond J; Lynch MP & Dawson JK (2004). "Association between bronchiectasis and smoking in patients with rheumatoid arthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 63 (8): 1001–2. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.015123. PMC 1755104. PMID 15249329.

- ↑ Sperber, Miriam (2012). Diffuse Lung Disorders: A Comprehensive Clinical-Radiological Overview. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 205. ISBN 9781447134404. Archived from the original on 2017-08-28.

- ↑ Morillas HN, Zariwala M, Knowles MR (2007). "Genetic Causes of Bronchiectasis: Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia". Respiration. 74 (3): 252–63. doi:10.1159/000101783. PMID 17534128.

- ↑ Dalrymple-Hay MJ, Lucas J, Connett G, Lea RE (1999). "Lung resection for the treatment of severe localized bronchiectasis in cystic fibrosis patients". Acta Chir Hung. 38 (1): 23–5. PMID 10439089.

- ↑ Handelsman DJ, Conway AJ, Boylan LM & Turtle JR (1984). "Young's syndrome. Obstructive azoospermia and chronic sinopulmonary infections". NEJM. 310 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM198401053100102. PMID 6689737.

- ↑ Notarangelo LD, Plebani A, Mazzolari E, Soresina A, Bondioni MP (2007). "Genetic causes of bronchiectasis: primary immune deficiencies and the lung". Respiration. 74 (3): 264–75. doi:10.1159/000101784. PMID 17534129.

- ↑ WILLIAMS H, CAMPBELL P (April 1960). "Generalized Bronchiectasis associated with Deficiency of Cartilage in the Bronchial Tree". Arch. Dis. Child. 35 (180): 182–91. doi:10.1136/adc.35.180.182. PMC 2012546. PMID 13844857.

- ↑ "Medical Problems and Treatments | The Marfan Trust". The Marfan Trust. Archived from the original on 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ↑ Shin MS, Ho KJ (1993). "Bronchiectasis in patients with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. A rare occurrence?". Chest. 104 (5): 1384–86. doi:10.1378/chest.104.5.1384. PMID 8222792.

- ↑ Catanzano, Tara (5 September 2005). "Primary Tuberculosis". eMedicine Specialties Encyclopedia. Connecticut: WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ↑ John M Holbert. "Bronchiectasis Imaging". Medscape. Archived from the original on 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2017-08-15. Updated: Oct 13, 2015

- ↑ Miller, JC (2006). "Pulmonary Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellular Infections in Women". Radiology Rounds. 4 (2).

- ↑ Crofton J (1966). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Bronchiectasis: I. Diagnosis". Br Med J. 1 (5489): 721–3 contd. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5489.721. PMC 1844268. PMID 5909486.

- ↑ Onen ZP, Eris Gulbay B, Sen E, Akkoca Yildiz O, Saryal S, Acican T, Karabiyikoglu G (2007). "Analysis of the factors related to mortality in patients with bronchiectasis". Respir Med. 101 (7): 1390–97. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.002. PMID 17374480.

- ↑ José, RJ; Brown, JS (October 2014). "Bronchiectasis". British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 75 Suppl 10: C146–51. doi:10.12968/hmed.2014.75.Sup10.C146. PMID 25289486.

- 1 2 Hnin, Khin; Nguyen, Chau; Carson, Kristin V.; Evans, David J.; Greenstone, Michael; Smith, Brian J. (2015-08-13). "Prolonged antibiotics for non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in children and adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD001392. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001392.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 26270620.

- ↑ Otgün I, Karnak I, Tanyel FC, Senocak ME, Büyükpamukçu N (2004). "Surgical treatment of bronchiectasis in children". J. Pediatr. Surg. 39 (10): 1532–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.06.009. PMID 15486899.

- ↑ Elborn JS, Johnston B, Allen F, Clarke J, McGarry J, Varghese G (1992). "Inhaled steroids in patients with bronchiectasis". Respir Med. 86 (2): 121–4. doi:10.1016/S0954-6111(06)80227-1. PMID 1615177.

- ↑ Waknine, Yael (27 July 2005). "Orphan Drug Approvals: Bronchitol, Prestara, GTI-2040". Medscape today for WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ↑ "Bronchiectasis, Chapter 4, Dean E. Schraufnagel (ed.)". Breathing in America: Diseases, Progress, and Hope. American Thoracic Society. 2010. Archived from the original on 2017-04-15. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ↑ McShane, PJ; Naureckas, E T; Tino, G; Strek, M E (2013). "Non–Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 188 (6): 230–35. doi:10.1164/rccm.201303-0411CI. PMID 23898922.

- ↑ Roguin, A (2006). "Rene Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781–1826): The Man Behind the Stethoscope". Clin Med Res. 4 (3): 230–35. doi:10.3121/cmr.4.3.230. PMC 1570491. PMID 17048358.

- ↑ Wrong O (2003). "Osler and my father". J R Soc Med. 96 (6): 462–64. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.9.462. PMC 539606. PMID 12949207.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bronchiectasis. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bronchiectasis. |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |