Fibrothorax

| Fibrothorax | |

|---|---|

| |

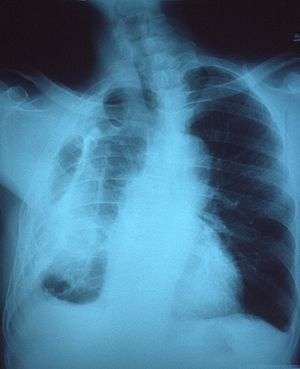

| Fibrothorax on chest x-ray | |

| Specialty | Respiratory medicine |

| Symptoms | Breathlessness |

| Usual onset | Adulthood |

| Duration | Long Term |

| Causes | Haemothorax, empyema, tuberculosis, uraemia, rheumatoid arthritis, pleurodesis, medications |

| Risk factors | Asbestos exposure |

| Diagnostic method | Chest X-ray, CT scan |

| Treatment | Watchful waiting, decortication |

| Prognosis | Variable |

| Frequency | Rare |

Fibrothorax is a medical condition characterised by scarring (fibrosis) of the pleural space surrounding the lungs that is severe enough to cause reduced movement of the lung and ribcage[1]. The main symptom of fibrothorax is shortness of breath. Fibrothorax may occur as a complication of many diseases, including infection of the pleural space known as an empyema or bleeding into the pleural space known as a haemothorax. Fibrosis in the pleura may be produced intentionally using a technique called pleurodesis to prevent recurrent punctured lung or pneumothorax, and the usually limited fibrosis that this produces can rarely be extensive enough to lead to fibrothorax.[2] The condition is most often diagnosed using an X-ray or CT scan. Fibrothorax is often treated conservatively but may require surgery.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms

Although fibrothorax may not cause any symptoms, the most commonly seen symptom associated with this condition is shortness of breath. [3] If shortness of breath is seen, it tends to occur gradually and may get worse over time. Less commonly, fibrothorax may cause chest discomfort or a dry cough [4]. As fibrothorax may occur as a complication of other diseases, symptoms are sometimes seen which reflect the underlying problem, for example fever in cases of empyema.

Signs

When someone with a fibrothorax is examined, several signs may point towards the diagnosis. Common signs include reduced movement of the ribcage during breathing and reduced breath sounds on the affected side(s), and a dull feeling when the chest is pressed.[4] Thickening of the nailfolds known as clubbing may be seen, but cyanosis is only rarely seen. In fibrothorax occurring only on one side, the trachea may be pulled towards the affected side. The pulse and breathing rate are usually normal.[5]

Causes

.png)

As a complication

Fibrothorax is often a complication of other disease that cause inflammation of the pleura. These include infections such as empyema or tuberculosis, or bleeding within the pleural space known as a haemothorax. It may also be caused by exposure to certain substances such as asbestos which can cause generalised fibrosis of the lungs which may involve the pleura.[6] Less common causes of fibrothorax include collagen vascular diseases, kidney failure leading to uraemia, and as a side effect of some medications. [2] The medications most commonly associated with fibrothorax are the ergot alkaloid drugs bromocriptine, pergolide, and methysergide. Fibrothorax may also occur without a clear underlying cause, in which case it is known as idiopathic fibrothorax. [7]

Iatrogenic fibrothorax

A technique called pleurodesis can be used to intentionally create scar tissue within the pleural space, usually as a treatment for repeated episodes of a punctured lung, known as a pneumothorax, or for malignant pleural effusions. While this procedure usually generates only limited scar tissue, in rare cases a fibrothorax can develop.[8]

Mechanism

Fibrosis can affect one or both of the two sheets of tissue forming the pleura - the visceral pleura adjacent to the lung and the parietal pleura adjacent to the ribcage. The term fibrothorax implies severe fibrosis affecting both the visceral and parietal pleura, fusing the lung to the chest wall. [1] Over time, generally over the course of years, the fibrotic scar tissue slowly tightens, resulting in the contraction of the contents of one or both halves of the chest and reducing the mobility of the ribs. [1] Within the chest, the lung is compressed and unable to expand, making it vulnerable to collapse and causing breathlessness.

Microscopic

At the microscopic level, the scar tissue is composed[9] of collagen fibres deposited in a basket weave pattern.[6] Usually, the underlying condition has to cause intense inflammation of the pleura, though it is unclear exactly how this results in fibrosis. It is suspected that a protein called Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β) plays a key role in producing fibrothorax, as this cytokine induces pleural fibrosis when given to animals. Furthermore, anti-TGF-β antibodies prevent fibrothorax in empyema.[2]

Diagnosis

Fibrothorax can be detected on a plain chest X-ray. In this case, thickening of the pleura that surround the lungs can be seen which if severe may also restrict the lung on the affected side causing a loss of lung volume. An X-ray may also detect calcification of the thickened pleura. There may be signs of the causative disease such as upper lobe consolidation in cases of tuberculosis. [10] Similar features to those seen on a plain X-ray can also be found on a CT scan. While mild pleural thickening may be more easily identified on a CT scan compared to a plain chest X-ray, in fibrothorax the severe thickening is easily identified. [11]

Treatment

Conservative

If possible, the underlying cause of the fibrothorax should be treated. In cases of fibrothorax caused by medication then these agents should be stopped. Some cases of fibrothorax can then be treated conservatively by watchful waiting as fibrothorax caused by tuberculosis, empyema, or hemothorax often improves spontaneously 3-6 months after the precipitating illness. During this time, drugs that might cause fibrosis to worsen such as ergot alkaloids should be avoided.[2]It is also vital to quit smoking, as that can have negative effect on the already diseased lungs.[12]

Surgical

In severe cases, the scar tissue causing fibrothorax can be surgically removed using a technique called decortication.[6] However, surgical decortication is an invasive procedure which carries the risk of complications including a small risk of death,[6] and is therefore generally only considered if severe symptoms are present and have been for many months. [13] The relative effectiveness of conservative treatment versus surgical decortication is unclear.[14] A pleurectomy can be done in the progressive case that fails to resolve, as it often is when asbestosis is the cause.[15]

Prognosis

The prognosis of decortication usually is good if the patient's overall health is good. The mortality of surgery is less than 1%, however, it is 4-6% in the elderly. The prognosis is favorable if neither of the three things occur: Complications, incomplete surgery, or underlying disease of the lungs.[15]If the cause is asbestosis, the prognosis for surgery is poor, likely since there also is pulmonary fibrosis. If the lung is extensively diseased, the air capacity can even reduce following surgery.[2]

Epidemiology

Though sporadic cases have been reported on medical literature, for example due or iatrogenic or postoperative complications, it is rare in developed countries, when there is a reduce in cases of tuberculosis. It is far more common is asbestos workers, with 5 to 13.5 percent of people affected. In that case, it can often be 15-20 years between initial exposure and visit to the doctor.[12]

Additional images

Extensive right fibrothorax.

Extensive right fibrothorax.

References

- 1 2 3 Huggins JT, Sahn SA (2004). "Causes and management of pleural fibrosis". Respirology. 9 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00630.x. PMID 15612954.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Broaddus, V. Courtney; Mason, Robert C.; Ernst, Joel D.; King, Talmadge E.; Lazarus, Stephen C.; Murray, John F.; Nadel, Jay A.; Slutsky, Arthur; Gotway, Michael (2015-03-17). Murray & Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323261937.

- ↑ Birdas, Thomas J.; Keenan, Robert J. (2009). Sugarbaker, David J.; Bueno, Raphael; Krasna, Mark J.; Mentzer, Steven J.; Zellos, Lambros, eds. Adult Chest Surgery. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies.

- 1 2 Birdas, Thomas J.; Keenan, Robert J. (2009). Sugarbaker, David J.; Bueno, Raphael; Krasna, Mark J.; Mentzer, Steven J.; Zellos, Lambros, eds. Adult Chest Surgery. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies.

- ↑ "Fibrothorax". Evidence Reviewed. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- 1 2 3 4 Donath, Joseph; Miller, Albert (2009). "Restrictive Chest Wall Disorders". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 30 (03): 275–292. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1222441. ISSN 1069-3424.

- ↑ Alhassan, Sulaiman; Fasanya, Adebayo; Thirumala, Raghu (2017-02-15). "Extensive Calcified Fibrothorax". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 195 (4): e25–e26. doi:10.1164/rccm.201606-1265im.

- ↑ "Fibrothorax - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ↑ Berkowitz, Rachel; Mangan, James; Mahal, Jacqueline; Siadecki, Sebastian D.; Rose, Gabriel; Sunderwirth, Ramona; Cramer, Kyle; Meyers, Brian K.; Oliveira, Carlos (May 2016). "Shortness of breath and unexpected imaging findings". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 34 (5): 938.e5–938.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.042. ISSN 0735-6757.

- ↑ "Fibrothorax - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ↑ Muzio, Bruno Di. "Fibrothorax with pleural thickening | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- 1 2 "Pleural Thickening of Lungs: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". Mesothelioma Center - Vital Services for Cancer Patients & Families. Retrieved 2018-05-28.

- ↑ Broaddus, V. Courtney; Mason, Robert C.; Ernst, Joel D.; King, Talmadge E.; Lazarus, Stephen C.; Murray, John F.; Nadel, Jay A.; Slutsky, Arthur; Gotway, Michael (2015-03-17). Murray & Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323261937.

- ↑ "Fibrothorax - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- 1 2 Moore, Jason (2015). Encyclopedia of Trauma Care. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 616–618. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-29613-0_130.