BMW

Bayerische Motoren Werke | |

BMW headquarters in Munich | |

| Aktiengesellschaft | |

| Traded as |

FWB: BMW DAX Component |

| Predecessor |

Rapp Motorenwerke Bayerische Flugzeugwerke |

| Founded | 7 March 1916 |

| Founder | Karl Rapp |

| Headquarters | Munich, Germany |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

Norbert Reithofer (Chairman) Harald Krüger (CEO) |

| Products | Luxury cars, motorcycles, engines |

| Brands | |

Production output |

|

| Revenue |

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Total assets |

|

| Total equity |

|

| Owner |

Stefan Quandt (29%) Susanne Klatten (21%) Public float (50%) |

Number of employees | 129,932 (2017)[1] |

| Subsidiaries |

List

|

| Website |

www.bmwgroup.com www.bmw.com |

BMW (German: [ˈbeːˈʔɛmˈveː]; originally an initialism for Bayerische Motoren Werke in German, or Bavarian Motor Works in English) is a German multinational company which currently produces luxury automobiles and motorcycles, and also produced aircraft engines until 1945.

The company was founded in 1916 and has its headquarters in Munich, Bavaria. BMW produces motor vehicles in Germany, Brazil, China, India, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In 2015, BMW was the world's twelfth largest producer of motor vehicles, with 2,279,503 vehicles produced.[2] The Quandt family are long-term shareholders of the company, with the remaining shares owned by public float.

Automobiles are marketed under the brands BMW (with sub-brands BMW M for performance models and BMW i for plug-in electric cars), Mini and Rolls-Royce. Motorcycles are marketed under the brand BMW Motorrad.

The company has significant motorsport history, especially in touring cars, Formula 1, sports cars and the Isle of Man TT.

History

1916–1923: Aircraft engine production

BMW's origins can be traced back to three separate German companies: Rapp Motorenwerke, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke and Automobilwerk Eisenach. The history of the name itself begins with Rapp Motorenwerke, an aircraft engine manufacturer. In April 1917, following the departure of the founder Karl Friedrich Rapp, the company was renamed Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW).[3](p11) BMW's first product was the BMW IIIa aircraft engine. The IIIa engine was known for good fuel economy and high-altitude performance.[4] The resulting orders for IIIa engines from the German military caused rapid expansion for BMW.

After the end of World War I in 1918, BMW was forced to cease aircraft-engine production by the terms of the Versailles Armistice Treaty.[5] To maintain in business, BMW produced farm equipment, household items and railway brakes. In 1922, former major shareholder Camillo Castiglioni purchased the rights to the name BMW, which led to the company descended from Rapp Motorenwerke being renamed Süddeutsche Bremse AG (known today as Knorr-Bremse). Castiglioni was also an investor in another aircraft company, called "Bayerische Flugzeugwerke", which he renamed BMW.[6]

The disused factory of Bayerische Flugzeugwerke was re-opened to produce engines for buses, trucks, farm equipment and pumps, under the brand name BMW. BMW's corporate history considers the founding date of Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (7 March 1916) to be the birth of the company.

1923–1939: Motorcycle and car production

As the restrictions of the Armistice Treaty began to be lifted, BMW began production of motorcycles in 1923,[7] with the R32 model.

BMW's production of automobiles began in 1928, when the company purchased the Automobilwerk Eisenach car company. Automobilwerk Eisenach's current model was the Dixi 3/15, a licensed copy of the Austin 7 which had begun production in 1927. Following the takeover, the Dixi 3/15 became the BMW 3/15, BMW's first production car.[8][9][10]

In 1932, the BMW 3/20 became the first BMW automobile designed entirely by BMW. It was powered by a four-cylinder engine, which BMW designed based on the Austin 7 engine.

BMW's first automotive straight-six engine was released in 1933, in the BMW 303. Throughout the 1930s, BMW expanded its model range to include sedans, coupes, convertibles and sports cars.

1939–1945: World War II

With German rearmament in the 1930s, the company again began producing aircraft engines for the Luftwaffe. The factory in Munich made ample use of forced labour: foreign civilians, prisoners of war and inmates of the Dachau concentration camp.[11] Among its successful World War II engine designs were the BMW 132 and BMW 801 air-cooled radial engines, and the pioneering BMW 003 axial-flow turbojet, which powered the tiny, 1944–1945–era jet-powered "emergency fighter", the Heinkel He 162 Spatz. The BMW 003 jet engine was first tested as a prime power plant in the first prototype of the Messerschmitt Me 262, the Me 262 V1, but in 1942 tests the BMW prototype engines failed on takeoff with only the standby Junkers Jumo 210 nose-mounted piston engine powering it to a safe landing.[12][13]

The few Me 262 A-1b test examples built used the more developed version of the 003 jet, recording an official top speed of 800 km/h (497 mph). The first-ever four-engine jet aircraft ever flown were the sixth and eighth prototypes of the Arado Ar 234 jet reconnaissance-bomber, which used BMW 003 jets for power. Through 1944 the 003's reliability improved, making it a suitable power plant for air frame designs competing for the Jägernotprogramm's light fighter production contract. which was won by the Heinkel He 162 Spatz design. The BMW 003 aviation turbojet was also under consideration as the basic starting point for a pioneering turboshaft powerplant for German armored fighting vehicles in 1944–45, as the GT 101.[14] Towards the end of the Third Reich, BMW developed some military aircraft projects for the Luftwaffe, the BMW Strahlbomber, the BMW Schnellbomber and the BMW Strahljäger, but none of them were built.[15][16]

1945–1959: Post-war rebuilding

During World War II, many BMW production facilities had been heavily bombed. BMW's facilities in East Germany were seized by the Soviet Union and the remaining facilities were banned by the Allies from producing motorcycles or automobiles. During this ban, BMW used basic secondhand and salvaged equipment to make pots and pans, later expanding to other kitchen supplies and bicycles.

In 1947, BMW was granted permission to resume motorcycle production and its first post-war motorcycle - the R24 - was released in 1948. BMW was still barred from producing automobiles, however the Bristol Aeroplane Company (BAC) was producing cars in England based on BMW's pre-war models, using plans that BAC had taken from BMW's German offices.

Production of automobiles resumed in 1952, with the BMW 501 large sedan. Throughout the 1950s, BMW expanded their model range with sedans, coupes, convertibles and sports cars. In 1954, the BMW 502 was BMW's first to use a V8 engine. To provide an affordable model, BMW began production of the Isetta micro-car (under licence from Iso) in 1955. Two years later, the four-seat BMW 600 was based on a lengthened version of the Isetta design. In 1959, the BMW 600 was replaced by the larger BMW 700 coupe/sedan.

1959–1968: Near bankruptcy and New Class

By 1959, BMW was in debt and losing money.[17] The Isetta was selling well but with small profit margins.[18] Their 501-based luxury sedans were not selling well enough to be profitable and were becoming increasingly outdated.[19] Their 503 coupé and 507 roadster were too expensive to be profitable.[19] Their 600, a four-seater based on the Isetta, was selling poorly.[20] The motorcycle market imploded in the mid-1950s with increasing affluence turning Germans away from motorcycles and toward cars.[21] BMW had sold their Allach plant to MAN in 1954.[22] American Motors and the Rootes Group had both tried to acquire BMW.[23]

At BMW's annual general meeting on 9 December 1959, Dr. Hans Feith, chairman of BMW's supervisory board, proposed a merger with Daimler-Benz. The dealers and small shareholders opposed this suggestion and rallied around a counter-proposal by Dr. Friedrich Mathern, which gained enough support to stop the merger.[18][23] At that time, the Quandt Group, led by half-brothers Herbert and Harald Quandt, had recently increased their holdings in BMW and had become their largest shareholder.[23] In 1960, the development program began for a new range of models, called the "Neue Klasse" (New Class) project. The resulting New Class four-door sedans, introduced in 1962, are credited for saving the company financially and establishing BMW's identity as a producer of leading sports sedans.

In 1965, the New Class range was expanded with the 2000 C and 2000 CS luxury coupes. The range was further expanded in 1966 with the iconic BMW 02 Series compact coupes.

BMW acquired the Hans Glas company based in Dingolfing, Germany, in 1966. Glas vehicles were briefly badged as BMW until the company was fully absorbed. It was reputed that the acquisition was mainly to gain access to Glas' development of the timing belt with an overhead camshaft in automotive applications,[24] although some saw Glas' Dingolfing plant as another incentive. However, this factory was outmoded and BMW's biggest immediate gain was, according to themselves, a stock of highly qualified engineers and other personnel.[25] The Glas factories continued to build a limited number of their existing models, while adding the manufacture of BMW front and rear axles until they could be closer incorporated into BMW.[26]

1968–1978: New Six, 3 Series, 5 Series, 7 Series

In 1968, BMW began production of its first straight-six engine since World War II. This engine coincided with the launch of the New Six large sedans (the predecessor to the 7 Series) and New Six CS large coupes (the predecessor to the 6 Series).

The first 5 Series range of mid-size sedans were introduced in 1972, to replace the New Class sedans. The 5 Series platform was also used for the 6 Series coupes, which were introduced in 1976. In 1975, the first model of the 3 Series range of compact sedans/coupes was introduced. The 7 Series large sedans were introduced in 1978.

1978–1989: M division

The 1978 BMW M1 was BMW's first mid-engined sports car and was developed in conjunction with Lamborghini. It was also the first road car produced by BMW's motorsport division, BMW M. In 1980, the M division produced its first model based on a regular production vehicle, the E12 M535i. The M535i is the predecessor to the BMW M5, which was introduced in 1985 based on the E28 platform.

In 1983, BMW introduced its first diesel engine, the M21. The first all-wheel drive BMW - the E30 325iX - began production in 1985, and in 1987 the E30 was BMW's first model produced in a wagon/estate body style.

The 1986 E32 750i was BMW's first V12 model. The E32 was also the first sedan to be available with a long-wheelbase body style (badged "iL" or "Li").

The BMW M3 was introduced in 1985, based on the E30 platform.

1989–1994: 8 Series, hatchbacks

The 8 Series range of large coupes was introduced in 1989 and in 1992 was the first application of BMW's first V8 engine in 25 years, the M60. It was also the first BMW to use a multi-link rear suspension, a design which was implemented for mass-production in the 1990 E36 3 Series.

The E34 5 Series, introduced in 1988, was the first 5 Series to be produced with all-wheel drive or a wagon body style.

In 1989, the limited-production Z1 began BMW's line of two-seat convertible Z Series models.

In 1993, the BMW 3 Series Compact was BMW's first hatchback model (except for the limited production 02 Series "Touring" models). These hatchback models formed a new entry-level model range below the other 3 Series models.

In 1992, BMW acquired a large stake in California-based industrial design studio DesignworksUSA, which they fully acquired in 1995.

The 1993 McLaren F1 is powered by a BMW V12 engine.

1994–1999: Rover ownership, Z3

_(cropped).jpg)

In 1994, BMW bought the British Rover Group[27] (which at the time consisted of the Rover, Land Rover, Mini and MG brands as well as the rights to defunct brands including Austin and Morris), and owned it for six years. By 2000, Rover was incurring huge losses and BMW decided to sell off several of the brands. The MG and Rover brands were sold to the Phoenix Consortium to form MG Rover, while Land Rover was taken over by Ford. BMW, meanwhile, retained the rights to build the new Mini, which was launched in 2001.

In 1995, the E38 725tds was the first 7 Series to use a diesel engine. The E39 5 Series was also introduced in 1995, and was the first 5 Series to use rack-and-pinion steering and a significant number of suspension parts made from lightweight aluminium.

The BMW Z3 two-seat convertible and coupe models were introduced in 1995. These were the first mass-produced models outside of the 1/3/5 Series and the first model to be solely manufactured outside Germany (in the United States, in this case).

In 1998, the E46 3 Series was introduced, with the M3 model featuring BMW's most powerful naturally aspirated engine to date.

1999–2006: SUV models, Rolls-Royce

_3.0d_01.jpg)

BMW's first SUV, the BMW X5 (E53), was introduced in 1999. The X5 was a large departure from BMW's image of sporting "driver's cars", however it was a very successful and resulted in other BMW X Series being introduced. The smaller BMW X3 was released in 2003.

The 2001 E65 7 Series was BMW's first model to use a 6-speed automatic transmission.

In 2002, the Z4 two-seat coupe/convertible replaced the Z3. In 2004, the 1 Series hatchbacks replaced the 3 Series Compact models as BMW's entry level models.

The 2003 Rolls-Royce Phantom was the first Rolls-Royce vehicle produced under BMW ownership. This was the end result of complicated contractual negotiations that began in 1998 when Rolls-Royce plc licensed use of the Rolls-Royce name and logo to BMW, but Vickers sold the remaining elements of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars to Volkswagen. In addition, BMW had supplied Rolls-Royce with engines since 1998 for use in the Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph.

In 2005, BMW's first V10 engine was introduced in the E60 M5. The E60 platform is also used for the E63/E64, which reintroduced the 6 Series models after a hiatus of 14 years.

2006–2013: Shift to turbocharged engines

_%E2%80%93_Frontansicht%2C_26._Juni_2011%2C_Ratingen.jpg)

BMW's first mass-production turbocharged petrol engine was the six-cylinder N54, which debuted in the 2006 E92 335i. In 2011, the F30 3 Series was released, with turbocharged engines being used on all models. This shift to turbocharging and smaller engines was reflective of general automotive industry trends. The M3 model based on the F30 platform is the first M3 to use a turbocharged engine.

BMW's first turbocharged V8 engine, the BMW N63, was introduced in 2008. Despite the trend to downsizing, in 2008 BMW began production of its first turbocharged V12 engine, the BMW N74. In 2011, the F10 M5 became the first M5 model to use a turbocharged engine.

In 2007, the production rights for Husqvarna Motorcycles was purchased by BMW for a reported 93 million euros.

The BMW X6 SUV was introduced in 2008. The X6 attracted controversy for its unusual combination of coupe and SUV styling cues.

In 2009, the BMW X1 compact SUV was introduced. The BMW 5 Series Gran Turismo fastback body style was also introduced in 2009, based on the 5 Series platform.

Controversial designer Chris Bangle announced his departure from BMW in February 2009, after serving on the design team for nearly seventeen years.[28]

BMW's first hybrid-powered car, the F01 ActiveHybrid 7, was introduced in 2010.

2013–present: Electric/hybrid power

_coupe_(25835062172).jpg)

BMW released their first electric car, the BMW i3 city car, in 2013. The i3 is also the first mass-production car to have a structure mostly made from carbon-fibre. BMW's first hybrid sportscar (and their first mid-engined car since the M1) is called the BMW i8 and was introduced in 2014. The i8 is also the first car to use BMW's first inline-three engine, the BMW B38.

In 2013, the BMW 4 Series replaced the coupe and convertible models of the 3 Series. Many elements of the 4 Series remained shared with the equivalent 3 Series model. Similarly, the BMW 2 Series replaced the coupe and convertible models of the 1 Series in 2013. The 2 Series was produced in coupe (F22), five-seat MPV (F45) and seven-seat MPV (F46) body styles. The latter two body styles are the first front-wheel drive vehicles produced by BMW. The F48 X1 also includes some front-wheel drive models.

The BMW X4 compact SUV was introduced in 2014.

The 2016 G11 740e and F30/F31 330e are the first plug-in hybrid versions of the 7 Series and 3 Series respectively.

Company name and logo

The name BMW is an abbreviation for Bayerische Motoren Werke (German pronunciation: [ˈbaɪ̯ʁɪʃə mɔˈtʰɔʁn̩ ˈvɛɐ̯kə] (![]()

The terms Beemer, Bimmer and Bee-em are commonly used slang for BMW in the English language[32][33] and are sometimes used interchangeably for cars and motorcycles.[34][35]

In the United States, some people prescribe that "beemer" should be used specifically for motorcycles and "bimmer" should be used for cars.[36][37][38][39][40][41] Some of these people claim that "true aficionados" make this distinction[42] and those who don't are "uninitiated."[43] Usage in North American mainstream media also varies, for example The Globe and Mail of Canada prefers Bimmer and calls Beemer a "yuppie abomination",[44] and the Tacoma News Tribune says that it is "auto snobs" who use the terms to distinguish between cars and motorcycles.[45]

The circular blue and white BMW logo or roundel evolved from the circular Rapp Motorenwerke company logo, from which the BMW company grew, combined with the blue and white colors of the flag of Bavaria.[46] The BMW logo still used today was created in 1917, albeit with various minor styling changes.[47]

The origin of the logo is often thought to be a portrayal of the movement of an aircraft propeller with the white blades cutting through a blue sky. However, this portrayal was first used in a BMW advertisement in 1929 - twelve years after the logo was created - so this is not the origin of the logo itself.[48]

Motorcycles

BMW began production of motorcycle engines and then motorcycles after World War I.[49] Its motorcycle brand is now known as BMW Motorrad. Their first successful motorcycle after the failed Helios and Flink, was the "R32" in 1923, though production originally began in 1921.[50] This had a "boxer" twin engine, in which a cylinder projects into the air-flow from each side of the machine. Apart from their single-cylinder models (basically to the same pattern), all their motorcycles used this distinctive layout until the early 1980s. Many BMW's are still produced in this layout, which is designated the R Series.

The entire BMW Motorcycle production has, since 1969, been located at the company's Berlin-Spandau factory.

During the Second World War, BMW produced the BMW R75 motorcycle with a sidecar attached. Having a unique design copied from the Zündapp KS750, its sidecar wheel was also motor-driven. Combined with a lockable differential, this made the vehicle very capable off-road, an equivalent in many ways to the Jeep.

In 1982, came the K Series, shaft drive but water-cooled and with either three or four cylinders mounted in a straight line from front to back. Shortly after, BMW also started making the chain-driven F and G series with single and parallel twin Rotax engines.

In the early 1990s, BMW updated the airhead Boxer engine which became known as the oilhead. In 2002, the oilhead engine had two spark plugs per cylinder. In 2004 it added a built-in balance shaft, an increased capacity to 1,170 cc and enhanced performance to 100 hp (75 kW) for the R1200GS, compared to 85 hp (63 kW) of the previous R1150GS. More powerful variants of the oilhead engines are available in the R1100S and R1200S, producing 98 and 122 hp (73 and 91 kW), respectively.

In 2004, BMW introduced the new K1200S Sports Bike which marked a departure for BMW. It had an engine producing 167 hp (125 kW), derived from the company's work with the Williams F1 team, and is lighter than previous K models. Innovations include electronically adjustable front and rear suspension, and a Hossack-type front fork that BMW calls Duolever.

BMW introduced anti-lock brakes on production motorcycles starting in the late 1980s. The generation of anti-lock brakes available on the 2006 and later BMW motorcycles pave the way for the introduction of electronic stability control, or anti-skid technology later in the 2007 model year.

BMW has been an innovator in motorcycle suspension design, taking up telescopic front suspension long before most other manufacturers. Then they switched to an Earles fork, front suspension by swinging fork (1955 to 1969). Most modern BMWs are truly rear swingarm, single sided at the back (compare with the regular swinging fork usually, and wrongly, called swinging arm). Some BMWs started using yet another trademark front suspension design, the Telelever, in the early 1990s. Like the Earles fork, the Telelever significantly reduces dive under braking.

BMW Group, on 31 January 2013, announced that Pierer Industrie AG has bought Husqvarna for an undisclosed amount, which will not be revealed by either party in the future. The company is headed by Stephan Pierer (CEO of KTM). Pierer Industrie AG is 51% owner of KTM and 100% owner of Husqvarna.

Automobiles

The current model lines of BMW automobiles are:

The 1 Series (F20/F21) is the entry level to BMW's current model range. It is produced in 3-door and 5-door hatchback body styles. A 4-door sedan variant (F52) is also sold in China.

_Sport_Line_5-door_hatchback_(2017-07-15)_01.jpg) F20 1 Series

F20 1 Series_in_Uruguay_-_front.jpg) F21 1 Series

F21 1 Series F52 1 Series

F52 1 Series

The 2 Series (F22/F23) is BMW's entry level coupes and convertibles. The 2 Series range also consists of the "Active Tourer" (F45) and "Gran Tourer" (F46) body styles, which are 5-seat and 7-seat MPVs respectively.

_coupe_(2018-07-30)_01.jpg) F22 2 Series

F22 2 Series F45 2 Series

F45 2 Series F46 2 Series

F46 2 Series

The 3 Series (F30/F31/F34) range is produced in 4-door sedan, 4-door wagon (estate) and 5-door fastback ("Gran Turismo") body styles. A long-wheelbase sedan variant (F35) is also sold in China.

_Luxury_Line_sedan_(2018-07-30)_01.jpg) F30 3 Series

F30 3 Series F31 3 Series

F31 3 Series_%E2%80%93_Frontansicht%2C_31._August_2013%2C_M%C3%BCnster.jpg) F34 3 Series

F34 3 Series F35 3 Series

F35 3 Series

The 4 Series (F32/F33/F36) range is produced in 2-door coupe, 2-door convertible and 5-door fastback ("Gran Coupe") body styles.

.jpg) F32 4 Series

F32 4 Series F33 4 Series

F33 4 Series_%E2%80%93_Frontansicht%2C_18._Oktober_2015%2C_D%C3%BCsseldorf.jpg) F36 4 Series

F36 4 Series

The 5 Series (G30/G31) range is produced in sedan and wagon body styles. A long-wheelbase sedan variant (G38) is also sold in China.

G30 5 Series

G30 5 Series G31 5 Series

G31 5 Series

The 6 Series (F06/F12/F13) range is produced in 2-door coupe, 2-door convertible and 4-door fastback ("Gran Coupe") body styles.

F06 6 Series

F06 6 Series- F12 6 Series

F13 6 Series

F13 6 Series

The 7 Series (G11/G12) range is produced in the 4-door sedan and long-wheelbase sedan body styles.

_sedan%2C_front_view.jpg) G11 7 Series

G11 7 Series_front_3.23.18.jpg) G12 7 Series

G12 7 Series

The X models consist of the X1 (F48), X2 (F39), X3 G01, X4 (G02), X5 (X5 (G05)) and X6 (F16).

F84 X1

F84 X1 F39 X2

F39 X2_xDrive20d_M_Sport_wagon_(2018-09-17)_01.jpg) G01 X3

G01 X3

G02 X4

G02 X4_sDrive25d_wagon_(2018-09-17)_01.jpg) F15 X5

F15 X5_M50d_wagon_(2015-07-14)_01.jpg) F16 X6

F16 X6

i models

The BMW i is a sub-brand of BMW founded in 2011 to design and manufacture plug-in electric vehicles.[51][52] The sub-brand initial plans called for the release of two vehicles; series production of the BMW i3 all-electric car began in September 2013,[53] and the market launch took place in November 2013 with the first retail deliveries in Germany.[54] The BMW i8 sports plug-in hybrid car was launched in Germany in June 2014.[55]

In 2014, BMW developed a prototype of street lights equipped with power sockets to charge electric cars, called Light and Charge.[56] Two of these charging facilities were installed at BMW's headquarters in Munich.[57] In 2015, BMW in cooperation with SCHERM Group has started deploying electric trucks on European roads, making it the first company to ever do so. The truck itself is manufactured by the Terberg Group, one of the world's largest independent specialist vehicle suppliers.[58][59][60]

Combined sales of the BMW i brand models reached the 50,000 unit milestone in January 2016.[61] Two years after its introduction, the BMW i3 ranked as the world's third best selling all-electric car in history.[62] Global sales of the BMW i3 achieved the 50,000 unit milestone in July 2016.[63]

In February 2016, BMW announced the introduction of the "iPerformance" model designation, which will be given to all BMW plug-in hybrid vehicles from July 2016. The aim is to provide a visible indicator of the transfer of technology from BMW i to the BMW core brand. The new designation will be used first on the plug-in hybrid variants of the latest BMW 7 Series.[64] Global sales of all BMW plug-in electrified models achieved the 100,000 unit milestone in early November 2016, consisting of more than 60,000 BMW i3s, over 10,000 BMW i8s, and about 30,000 from combined sales of all BMW iPerformance plug-in hybrid models.[65]

As of November 2016, four BMW electrified models have been released, the BMW X5 xDrive40e iPerformance, BMW 225xe iPerformance Active Tourer, BMW 330e iPerformance, and the BMW 740e iPerformance.[66] The BMW 530e iPerformance is scheduled to be released in Europe March 2017 as part of the upcoming seventh generation BMW 5 Series lineup.[67] Global sales of all plug-in electrified models achieved the 100,000 unit milestone in early November 2016, consisting of more than 60,000 i3s, over 10,000 i8s, and about 30,000 from combined sales of all BMW iPerformance plug-in hybrid models.[65] Combined global sales of BMW’s electrified models totaled more than 62,000 units in 2016,[68] and 103,080 in 2017, including MINI brand electrified vehicles.[69] Cumulative global sales of BMW Group's electrified vehicles passed the 250,000 unit milestone in April 2018.[70]

M models

_coupe_(24220553394).jpg)

BMW produce a number of high-performance derivatives of their cars developed by their BMW M GmbH (previously BMW Motorsport GmbH) subsidiary.

The current M models are:

Naming convention for models

Sometimes the model series are referred to by their German pronunciation: "Einser" ("One-er") for the 1 Series, "Dreier" ("Three-er") for the 3 Series, "Fünfer" ("Five-er") for the 5 Series, "Sechser" ("Six-er") for the 6 Series and "Siebener" ("Seven-er") for the 7 Series. These are not actually slang, but are the normal way that such letters and numbers are pronounced in German.[71]

Motorsport

BMW has a long history of motorsport activities, including:

- Touring cars, such as DTM, WTCC, ETCC and BTCC

- Formula One

- Endurance racing, such as 24 Hours Nürburgring, 24 Hours of Le Mans, 24 Hours of Daytona and Spa 24 Hours

- Isle of Man TT

- Dakar Rally

- American Le Mans Series

- Formula BMW – a junior racing Formula category.

- Formula Two

.jpg) 2016 BMW M4 DTM

2016 BMW M4 DTM 2016 BMW M6 GT3

2016 BMW M6 GT3 2016 BMW S1000RR

2016 BMW S1000RR

Involvement in the arts

Manufacturers employ designers for their cars, but BMW has made efforts to gain recognition for exceptional contributions to and support of the arts, including art beyond motor vehicle design. These efforts typically overlap or complement BMW's marketing and branding campaigns.[72]

Art Cars

In 1975, Alexander Calder was commissioned to paint the 3.0CSL driven by Hervé Poulain at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, which became the first in the series of BMW Art Cars. This led to more BMW Art Cars, painted by artists including Andy Warhol, Jenny Holzer, Roy Lichtenstein and others. The cars, currently numbering 17, have been shown at the Louvre, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and New York's Grand Central Terminal.[73]

1975 3.0 CSL Art Car by Alexander Calder

1975 3.0 CSL Art Car by Alexander Calder- 1979 M1 Art Car by Andy Warhol

2010 M3 GT2 Art Car by Jeff Koons

2010 M3 GT2 Art Car by Jeff Koons

Architecture

BMW's Munich headquarters represents the cylinder head of a 4-cylinder engine. It was designed by Karl Schwanzer and was completed in 1972. The building has become a European icon[73] and was declared a protected historic building in 1999. The main tower consists of four vertical cylinders standing next to and across from each other. Each cylinder is divided horizontally in its center by a mold in the facade. Notably, these cylinders do not stand on the ground; they are suspended on a central support tower.

BMW Museum is a futuristic cauldron-shaped building, which was also designed by Karl Schwanzer and opened in 1972.[74] The interior has a spiral theme and the roof is a 40-metre diameter BMW logo.

BMW's exhibition space in Munich, BMW Welt, was designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au and opened in 2007. It includes a showroom and lifting platforms where a customer's new car is theatrically unveiled to the customer.[75]

The BMW Central Building in Leipzig was designed by Zaha Hadid.

BMW Museum interior

BMW Museum interior BMW Welt

BMW Welt

Film

In 2001 and 2002, BMW produced a series of 8 short films called The Hire, which had plots based around BMW models being driven to extremes by Clive Owen.[76] The directors for The Hire included Guy Ritchie, John Woo, John Frankenheimer and Ang Lee. In 2016, a ninth film in the series was released.

The 2006 "BMW Performance Series" was a marketing event geared to attract black car buyers. It included the "BMW Pop-Jazz Live Series" - a tour headlined by jazz musician Mike Phillips - and the "BMW Blackfilms.com Film Series" highlighting black filmmakers.[77]

Visual arts

BMW was the principal sponsor of the 1998 The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and other Guggenheim museums, though the financial relationship between BMW and the Guggenheim was criticised in many quarters.[78][79]

In 2012, BMW began sponsoring Independent Collectors production of the BMW Art Guide, which is the first global guide to private and publicly accessible collections of contemporary art worldwide.[80] The 2016 edition features 256 collections from 43 countries.

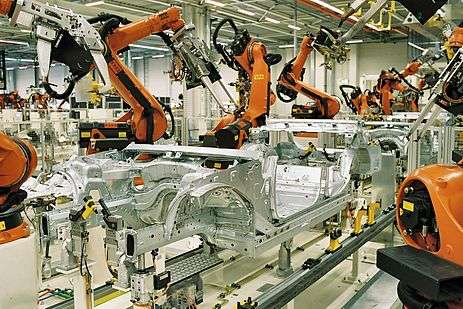

Production

BMW produces complete automobiles at its factories in Germany (Munich, Dingolfing, Regensburg and Leipzig), United States (Greer, South Carolina),[81] South Africa (Rosslyn) and China (Shenyang). BMW also has local assembly operation using complete knock down components in Thailand, Russia, Egypt, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India (Chennai), for 3, 5, 7 series and X3.[82]

In 2006, the BMW group (including Mini and Rolls-Royce) produced 1,366,838 four-wheeled vehicles, which were manufactured in five countries.[83] In 2010, it manufactured 1,481,253 four-wheeled vehicles and 112,271 motorcycles (under both the BMW and Husqvarna brands).[84]

BMW Motorcycles are being produced at the company's Berlin factory, which earlier had produced aircraft engines for Siemens.

By 2011, about 56% of BMW-brand vehicles produced are powered by petrol engines and the remaining 44% are powered by diesel engines. Of those petrol vehicles, about 27% are four-cylinder models and about nine percent are eight-cylinder models.[85] On average, 9,000 vehicles per day exit BMW plants, and 63% are transported by rail.[86]

Annual production since 2005 is as follows:

| Year | BMW | MINI | Rolls-Royce | Motorcycle* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,122,308 | 200,119 | 692 | 92,013 |

| 2006 | 1,179,317 | 186,674 | 847 | 103,759 |

| 2007 | 1,302,774 | 237,700 | 1,029 | 104,396 |

| 2008 | 1,203,482 | 235,019 | 1,417 | 118,452 |

| 2009 | 1,043,829 | 213,670 | 918 | 93,243 |

| 2010 | 1,236,989 | 241,043 | 3,221 | 112,271 |

| 2011 | 1,440,315 | 294,120 | 3,725 | 110,360 |

| 2012 | 1,547,057 | 311,490 | 3,279 | 113,811 |

| 2013 | 1,699,835 | 303,177 | 3,354 | 110,127 |

| 2014 | 1,838,268 | 322,803 | 4,495 | 133,615 |

| 2015 | 1,933,647 | 342,008 | 3,848 | 151,004 |

Major issues/recalls

In November 2016, BMW recalled 136,000 2007–2012 model year U.S. cars for fuel pump wiring problems possibly resulting in fuel leak and engine stalling or restarting issues.[87]

In May 2017, ABC News reported on an investigation, in which they found dozens of instances of parked BMW cars catching fire, including some parked in home garages.[88]

In fall 2017, BMW recalled roughly a million cars and SUVs for fire risk. One recall was for 672,000 3 Series cars from model years 2006-11 with climate control system electronic components at risk of overheating. The second recall was for 740,000 six-cylinder models (328i, 525i), at risk of crankcase heating short-circuit; some Series 3 cars were subject to both recalls.[89]

In August 2018, BMW recalled 106,000 diesel vehicles in South Korea with a defective exhaust gas recirculation module after some cars caught on fire, then expanded the recall to 324,000 more cars in Europe.[90]

Sales

Vehicles sold in all markets according to BMW's annual reports.

| Year | BMW | MINI | Rolls-Royce | Motorcycle* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,126,768 | 200,428 | 797 | 97,474 |

| 2006 | 1,185,089 | 188,077 | 805 | 100,064 |

| 2007 | 1,276,793 | 222,875 | 1,010 | 102,467 |

| 2008 | 1,202,239 | 232,425 | 1,212 | 115,196 |

| 2009 | 1,068,770 | 216,538 | 1,002 | 100,358 |

| 2010 | 1,224,280 | 234,175 | 2,711 | 110,113 |

| 2011 | 1,380,384 | 285,060 | 3,538 | 113,572 |

| 2012 | 1,540,085 | 301,525 | 3,575 | 117,109 |

| 2013 | 1,655,138 | 305,030 | 3,630 | 115,215** |

| 2014 | 1,811,719 | 302,183 | 4,063 | 123,495** |

| 2015 | 1,905,234 | 338,466 | 3,785 | 136,963** |

* Since 2008, motorcycle productions and sales figures include Husqvarna models.

** Excluding Husqvarna, sales volume up to 2013: 59,776 units.

In China, BMW sold 415,200 vehicles between January and November 2014, through a network of over 440 BMW stores and 100 Mini stores.[91]

Industry collaboration

BMW has collaborated with other car manufacturers on the following occasions:

- McLaren Automotive: BMW designed and produced the V12 engine that powered the McLaren F1.[92][93]

- Peugeot and Citroën: Joint production of four-cylinder petrol engines, beginning in 2004.[94]

- Daimler Benz: Joint venture to produce the hybrid drivetrain components used in the ActiveHybrid 7.[95][96]

- Toyota: Three-part agreement in 2013 to jointly develop fuel cell technology, develop a joint platform for a sports car (for the 2018 BMW Z4 (G29) and Toyota Supra) and research lithium-air batteries.[97][98][99]

- Audi and Mercedes: Joint purchase of Nokia's Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps) in 2015.[100]

Sponsorships

In soccer (football), BMW sponsors Bundesliga club Eintracht Frankfurt.[101]

At the London 2012 Olympic games, BMW's sponsorship included providing 4000 BMWs and Minis.[102] BMW also made a six-year sponsorship deal with the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) in July 2010.[103][104]

In golf, BMW has sponsored various events,[105] including the PGA Championship,[106][107] the BMW Italian Open, the BMW Masters in China[108][109] and the BMW International Open in Germany.[110]

In rugby, BMW sponsored the South Africa national rugby union team from 2011 to 2015.[111][112]

Hungarian member firm is strategic sponsor of Brain Bar, a Budapest-based, annually held festival on the future.[113]

Environmental record

BMW is a charter member of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) National Environmental Achievement Track, which recognizes companies for their environmental stewardship and performance.[114] It is also a member of the South Carolina Environmental Excellence Program.[115]

Since 1999, BMW has been named the world's most sustainable automotive company every year by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.[116] The BMW Group is one of three automotive companies to be featured every year in the index.[117] In 2001, the BMW Group committed itself to the United Nations Environment Programme, the UN Global Compact and the Cleaner Production Declaration. It was also the first company in the automotive industry to appoint an environmental officer, in 1973.[118] BMW is a member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.[119]

In 2012, BMW was the highest automotive company in the Carbon Disclosure Project's Global 500 list, with a score of 99 out of 100.[120][121] The BMW Group was rated the most sustainable DAX 30 company by Sustainalytics in 2012.[122]

To reduce vehicle emissions, BMW is improving the efficiency of existing fossil-fuel powered models, while researching electric power, hybrid power and hydrogen for future models.[123]

During the first quarter of 2018, BMW sold 26,858 Electrified Vehicles (EVs, PHEVs, & Hybrids)

Bicycles

BMW branded bicycles are sold online and through dealerships.[124] The BMW Turbo Levo FSR 6Fattie electric mountain bike was produced in partnership with Specialized and the BMW Cruise e-Bike NBG III uses a Bosch motor and battery.[125][126]

Car-sharing services

DriveNow is a joint-venture between BMW and Sixt that was launched in Munich in June 2011, and now operates in thirteen cities around Europe. As of December 2012,[127] DriveNow operates over 1,000 vehicles, which serve five cities worldwide and over 60,000 customers.[128]

In the United States, BMW launched the ReachNow car-sharing service in Seattle in April 2016.[129] ReachNow currently operates in Seattle, Portland and Brooklyn.

Overseas subsidiaries

Brazil

On 9 October 2014, BMW's new South American automobile plant in Araquari, Santa Catarina assembled its first car, an F30 3 Series.[130] The cars assembled at Araquari are the F20 1 Series, F30 3 Series, F48 X1, F25 X3 and Mini Countryman.[131] Cars are assembled from complete knock-down components.[132]

Canada

BMW's first dealership in Canada, located in Ottawa, was opened in 1969.[133] In 1986, BMW established a head office in Canada.[134]

BMW sold 28,149 vehicles in Canada in 2008.[135]

China

Signing a deal in 2003 for the production of sedans in China,[136] May 2004 saw the opening of a factory in the North-eastern city of Shenyang where Brilliance Auto produces BMW-branded automobiles[137] in a joint venture with the German company.[138]

Egypt

Bavarian Auto Group became sole importer of the BMW and Mini brands in 2003.

At the BMW assembly plant in 6th of October City, the 3 Series, 5 Series, 7 Series, X1 and X3 are assembled from complete knock-down components.[131]

India

BMW India was established in 2006 as a sales subsidiary in Gurugram.

A BMW assembly plant was opened in Chennai in 2007, assembling 3 Series, 5 Series, 7 Series, X1, X3, X5, Mini Countryman and motorcycle models from complete knock-down components.[131][139]

Japan

BMW Japan Corp, a wholly owned subsidiary, imports and distributes BMW vehicles in Japan.[140]

Mexico

In July 2014, BMW announced it was establishing a plant in Mexico, in the city and state of San Luis Potosi involving an investment of $1 billion. The plant will employ 1,500 people, and produce 150,000 cars annually, commencing in 2019.[141]

South Africa

BMWs have been assembled in South Africa since 1968,[142] when Praetor Monteerders' plant was opened in Rosslyn, near Pretoria. BMW initially bought shares in the company, before fully acquiring it in 1975; in so doing, the company became BMW South Africa, the first wholly owned subsidiary of BMW to be established outside Germany. Unlike United States manufacturers, such as Ford and GM, which divested from the country in the 1980s, BMW retained full ownership of its operations in South Africa.

Following the end of apartheid in 1994, and the lowering of import tariffs, BMW South Africa ended local production of the 5 Series and 7 Series, in order to concentrate on production of the 3 Series for the export market. South African–built BMWs are now exported to right hand drive markets including Japan, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa. Since 1997, BMW South Africa has produced vehicles in left-hand drive for export to Taiwan, the United States and Iran, as well as South America.

Three unique models that BMW Motorsport created for the South African market were the E23 M745i (1983), which used the M88 engine from the BMW M1, the BMW 333i (1986), which added a six-cylinder 3.2-litre M30 engine to the E30,[143] and the E30 BMW 325is (1989) which was powered by an Alpina-derived 2.7-litre engine.

BMWs with a VIN starting with "NC0" are manufactured in South Africa.

United States

BMW cars have been officially sold in the United States since 1956[144] and manufactured in the United States since 1994.[145] The first BMW dealership in the United States opened in 1975.[146] In 2016, BMW was the twelfth highest selling brand in the United States.[147]

The manufacturing plant in Greer, South Carolina has the highest production of the BMW plants worldwide,[148] currently producing approximately 1,400 vehicles per day.[149] The models produced at the Spartanburg plant are the X3, X4, X5, X6 and X7 SUV models.

In addition to the South Carolina manufacturing facility, BMW's North American companies include sales, marketing, design, and financial services operations in the United States, Mexico, Canada and Latin America.

Hungary

On July 31, 2018, BMW announced to build 1 billion euro car factory in Hungary. The new plant, to be built near the city of Debrecen about 230 kilometers east of Budapest, will have a production capacity of 150,000 cars a year.[150]

Marketing

Slogan

The slogan 'The Ultimate Driving Machine' was first used in North America in 1974.[151][152] In 2010, this long-lived campaign was mostly supplanted by a campaign intended to make the brand more approachable and to better appeal to women, 'Joy'. By 2012 BMW had returned to 'The Ultimate Driving Machine'.[153]

April Fools

BMW has garnered a reputation in Britain over the years for its April Fools pranks, which are printed in the press there every year. In 2010, they ran an advertisement in The Guardian announcing that customers would be able to order BMWs with different coloured badges to show their affiliation with the political party they supported.[154]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to BMW. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Annual Report 2017" (PDF). BMW Group. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ "WORLD MOTOR VEHICLE PRODUCTION - OICA correspondents survey" (PDF). www.oica.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Noakes, Andrew (2008). The Ultimate History of BMW. Parragon Publishing.

- ↑ "BMW Model IIIA – Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum". Nasm.si.edu. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ↑ "Fliegerschule St.Gallen – history" (in German). Archived from the original on 28 May 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ↑ "When was BMW founded?". BMW Education. BMW. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ Darwin Holmstrom, Brian J. Nelson (2002). BMW Motorcycles. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1098-4. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ↑ Johnson, Richard Alan (2005). Six men who built the modern auto industry. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1958-1.

- ↑ Oppat, Kay (2008). Disseminative Capabilities: A Case Study of Collaborative Product Development in the Automotive. Gabler Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8349-1254-1.

- ↑ Kiley, David (2004). Driven: inside BMW, the most admired car company in the world. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26920-5.

- ↑ "MUNICH-ALLACH: WORKING FOR BMW". www.ausstellung-zwangsarbeit.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Pavelec, Sterling Michael (2007). The Jet Race and the Second World War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99355-9.

- ↑ Radinger, Will; Schick., Walter (1996). Me262 (in German). Berlin: Avantic Verlag GmbH. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-925505-21-8.

- ↑ Kay, Anthony (2002). German Jet Engine and Gas Turbine Development 1930–1945. Airlife Publishing. ISBN 9781840372946.

- ↑ "BMW Strahljager Project I". Nevingtonwarmuseum.weebly.com. 3 November 1944. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ Dan Johnson. "BMW Aircraft". Luft46.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ Norbye, p. 134

- 1 2 Noakes, p. 57

- 1 2 Norbye, p. 130

- ↑ Noakes, pp. 56–57

- ↑ Norbye, pp. 119–120

- ↑ Norbye, p. 119

- 1 2 3 Norbye, p. 132

- ↑ Toronto Star 3 July 2004

- ↑ Becker, Clauspeter (1971), Logoz, Arthur, ed., "BMW 2500/2800", Auto-Universum 1971 (in German), Zürich, Switzerland: Verlag Internationale Automobil-Parade AG, XIV: 73

- ↑ Becker, p. 74

- ↑ Albrecht Rothacher (2004). Corporate Cultures And Global Brands. World Scientific. p. 239. ISBN 978-981-238-856-8.

- ↑ "Chris Bangle". Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Hans List: Vorwort und Einführung zum Gesamtwerk. Band 1 von Die Verbrennungskraftmaschine, Springer, Wien, 1949. ISBN 9783662294888. Verzeichnis der Abkürzungen

- ↑ Roland Löwisch: BMW - Die schönsten Modelle: 100 Jahre Design und Technik. HEEL, 2016, ISBN 9783958434066. p 7.

- ↑ "BMW 1970s brochure for the United States" (PDF). www.bmw-grouparchiv.de. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ↑ "Bee em / BMW Motorcycle Club of Victoria Inc". National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ↑ "No Toupees allowed". Bangkok Post. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ↑ Lighter, Jonathan E. (1994). Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang: A-G. 1. Random House. pp. 126–27. ISBN 978-0-394-54427-4.

Beemer n. [BMW + ''er''] a BMW automobile. Also Beamer. 1982 S. Black Totally Awesome 83 BMW ("Beemer"). 1985 L.A. Times (13 April) V 4: Id much rather drive my Beemer than a truck. 1989 L. Roberts Full Cleveland 39: Baby boomers... in... late-model Beemers. 1990 Hull High (NBC-TV): You should ee my dad's new Beemer. 1991 Cathy (synd. cartoon strip) (21 April): Sheila... [ground] multi-grain snack chips crumbs into the back seat of my brand-new Beamer! 1992 Time (18 May) 84: Its residents tend to drive pickups or subcompacts, not Beemers or Rolles.

- ↑ Lighter, Jonathan E. (1994). Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang: A-G. 1. Random House. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-394-54427-4.

Bimmer n. Beemer.

- ↑ "Bimmer vs. Beemer". boston-bmwcca.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- ↑ Duglin Kennedy, Shirley (2005). The Savvy Guide to Motorcycles. Indy Tech Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7906-1316-1.

Beemer – BMW motorcycle; as opposed to Bimmer, which is a BMW automobile.

- ↑ Yates, Brock (12 March 1989). "You Say Porsch and I Say Porsch-eh". The Washington Post. p. w45. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014.

'Bimmer' is the slang for a BMW automobile, but 'Beemer' is right when referring to the company's motorcycles.

- ↑ Zesiger, Sue (26 June 2000). "Why Is BMW Driving Itself Crazy? The Rover deal was a dog, but it didn't cure BMW's desire to be a big-league carmaker—even if that means more risky tactics". Fortune Magazine. CNN. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013.

Bimmers (yes, it's 'Bimmer' for cars—the often misused 'Beemer' refers only to the motorcycles).

- ↑ Herchenroether, Dan; SellingAir, LLC (2004). Selling Air: A Tech Bubble Novel. SellingAir, LLC. ISBN 978-0-9754224-0-3.

- ↑ "International – Readers Report. Not All BMW Owners Are Smitten". Business Week. The McGraw-Hill Companies. 30 June 2003. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012.

Editor's note: Both nicknames are widely used, though Bimmer is the correct term for BMW cars, Beemer for BMW motorcycles. A Google search yields approximately 10 times as many references to Bimmer as to Beemer.

- ↑ Morsi, Pamela (2002). Doing Good. Mira. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-55166-884-0.

True aficionados know that the nickname Beemer actually refers to the BMW motorcycle. Bimmer is the correct nickname for the automobile

- ↑ Hoffmann, Peter (1998). "Hydrogen & fuel cell letter". Peter Hoffmann.

For the uninitiated, a Bimmer is a BMW car, and a Beemer is a motorcycle.

- ↑ English, Bob (7 April 2009). "Why wait for spring? Lease it now". The Globe and Mail. Toronto, CA: CTVglobemedia Publishing. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013.

If you're a Bimmer enthusiast (not that horrible leftover 1980s yuppie abomination Beemer), you've undoubtedly read the reviews,

- ↑ The Nose: FWay students knew who they were voting for in school poll [South Sound Edition]. 25 October 2002. The News Tribune, p. B01. Retrieved 6 July 2009, from ProQuest Newsstand. (Document ID: 223030831) |quote=We're told by auto snobs that the word 'beemer' actually refers to the BMW motorcycle, and that when referring to a BMW automobile, the word's pronounced 'bimmer.'

- ↑ BMW. "The origin of the BMW logo". Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ↑ "BMW logo". www.bmwdrives.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Stephen Williams (7 January 2010). "BMW Roundel: Not Born From Planes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ↑ Peter Gantriis, Henry Von Wartenberg. "The Art of BMW: 85 Years of Motorcycling Excellence". MotorBooks International, September 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ "What is the history of BMW motorcycles in the USA?". Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- ↑ Joe Lorio (May 2010). "Green: Rich Steinberg Interview: Electric Bimmer Man". Automobile Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "BMW introduces new i sub-brand, first two vehicles i3 and i8; premium mobility services and new venture capital company". Green Car Congress. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ Sebastian Blanco (18 September 2013). "BMW i3 starts production in Germany using local wind power, US carbon fiber". Autoblog Green. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Jay Cole (15 November 2013). "BMW Delivers First i3 Electric Vehicles In Germany Today". InsideEVs.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ Eric Loveday (6 June 2014). "World's First BMW i8 Owners Take Delivery In Germany". InsideEVs.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ↑ "BMW develops street lights with electric car-charging sockets". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "BMW Tests Street Lights With Electric Car Charging Sockets". www.motorauthority.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ↑ Vincent, James (15 November 2015). "BMW is first to deploy an electric 40-ton truck on European roads". The Verge. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Group puts another 40t battery-electric truck into service". Electric Vehicle News. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Shahan, Zachary (10 June 2015). "BMW & SCHERM Pilot 40-Ton Electric Truck". Clean Technica. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Cobb, Jeff (15 February 2016). "BMW Sells its 50,000th i-Series Worldwide in January". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016. A total of 41,586 i3s and 7,197 i8s have been sold worldwide through December 2015.

- ↑ "The BMW i3 turns two. Time for an interim review. In Germany the BMW i3 has been the best-selling electric car since it was launched. In the worldwide ranking it stands third" (Press release). Munich: BMW Group. 12 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ Cobb, Jeff (1 August 2016). "Renault Zoe and BMW i3 Join The 50,000 Sales Club". HybridCars.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "BMW at the 86th Geneva International Motor Show 2016" (Press release). Munich: BMW Group PressClub Global. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- 1 2 "Three years since the market launch of BMW i. 100,000 electrified BMW on the road" (Press release). Munich: BMW Group Press Club Global. 3 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016. Three year after the market launch of the BMW i3, the BMW Group has delivered more than 100,000 purely electric-powered cars and plug-in hybrids to customers worldwide. The BMW i3 alone has reached more than 60,000 units, making it the most successful electric vehicle in the premium compact segment. The BMW i8 ranks first among electrified sports cars, with more than 10,000 delivered since the middle of 2014. Additionally, there are the approximately 30,000 iPerformance plug-in hybrids sold.

- ↑ BMW Group (November 2016). "Electrified by BMW i - BMW iPerformance: Plug-in hybrids with BMW i know-how". BMW.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ Cole, Jay (13 October 2016). "BMW 530e iPerformance Debuts, Arrives In March – Specs, Video". InsideEVs.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ "BMW Group achieves sixth consecutive all-time sales high and remains world's leading premium car company" (Press release). Munich: BMW Group Global. 9 January 2017. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Record sales for BMW Group worldwide during 2017 while it boosts the Premium car market in Mexico, Latin America and the Caribbean" (Press release). Mexico City: BMW Group. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018. The BMW Group delivered a total of 103,080 plug-in electric cars in 2017 worldwide, including MINI plug-in hybrid models. Of these, 31,482 were i3s.

- ↑ "More than a quarter of a million electrified BMW Group vehicles on the roads after strong April sales growth" (Press release). Munich: BMW Group. 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ↑ Schmitt, Peter A (2004). Langenscheidt Fachwörterbuch Technik und Angewandte Wissenschaften: Englisch – Deutsch / Deutsch – Englisch (2nd ed.). Langenscheidt Fachverlag. ISBN 978-3-86117-233-8.

- ↑ "BMW Commissions Artists for Auto Werke Art Project". Art Business News. 27 (13). 2000. p. 22.

- 1 2 Patton, Phil (12 March 2009). "These Canvases Need Oil and a Good Driver". The New York Times. p. AU1. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017.

- ↑ "Touring the Temples of German Automaking". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ↑ Schmitt, Bernd; Van Zutphen, Glenn (2012), Happy Customers Everywhere: How Your Business Can Profit from the Insights of Positive Psychology, Macmillan, p. 64, ISBN 9781137000460, archived from the original on 19 March 2018

- ↑ "BMW Films". Archived from the original on 25 June 2007.

- ↑ "BMW arts series aims at black consumers". Automotive News. 80 (6215). 7 August 2006. p. 37.

- ↑ ""Economist, The (US) (21 April 2001). "When merchants enter the temple; Marketing museums". The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010.

- ↑ Vogel, Carol (3 August 1998). "Latest Biker Hangout? Guggenheim Ramp". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "About the Guide – »I don't think anybody has been to all these places.«". www.bmw-art-guide.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ "Contact Us". www.bmwusfactory.com. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ↑ "BMW Group". BMW Group. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ↑ "World Motor Vehicle Production, OICA correspondents survey 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ↑ "Annual Report 2010" (PDF). BMW Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ Hilton Holloway (11 February 2011). "The future of BMW's engines". Autocar. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Christopher Ludwig (22 December 2016). "BMW's 'connected' logistics: Shaping a self-steering supply chain". Automotive Logistics. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

logistics as the "heart of BMW's production system": 30m parts per day move from 1,800 suppliers; 7,000 sea freight containers per day, and in a year 84m cubic metres across ocean, road, rail and air freight. Outbound, around 9,000 vehicles leave BMW plants each day on their way to 4,500 dealers in 160 countries. 63% of cars leave plants by train

- ↑ Atiyeh, Clifford. "BMW Recalls 136,000 Cars for Fuel Leaks and Stalling". Car and Driver. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ "Parked BMWs bursting into flames leave owners with questions". ABC News. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Caron, Christina. "BMW Recalls Roughly a Million Vehicles at Risk of Catching Fire". New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Randewich, Noel; Duguid, Kate. "BMW recalls 324,000 cars in Europe after Korean engine fires: FAZ". Reuters. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ "BMW to Pay $820 Million to China Car Dealers, Group Says". Bloomberg News. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "McLaren F1 Supercar". www.caranddriver.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "Jay Leno Pulls Out McLaren F1's V12 Engine for All to See". www.carscoops.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "PSA, BMW Collaboration Grows". www.wardsauto.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "2010 BMW ActiveHybrid 7 Review". www.topspeed.com. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "2010 BMW ActiveHybrid 7 – Official Information". www.bmwblog.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Group and Toyota Motor Corporation Deepen Collaboration by Signing Binding Agreements". www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW, Toyota Confirm Hydrogen Fuel Cell, Technology Deals". 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016.

- ↑ "BMW and Toyota sign Agreement for Fuel Cell System, Sports Vehicle, Lightweight Technology and Lithium-air Battery". www.bmwblog.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "Nokia sells Here maps unit to Audi, BMW, and Mercedes for $3 billion". www.theverge.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ "German champions Borussia Dortmund join solar trend". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "BMW chosen to provide official Minis for 2012 London Olympics". The Times. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ↑ "BMW, USOC make 6-year sponsorship deal official". www.teamusa.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW to sponsor America's Olympic committee". www.autonews.com. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Int'l Sponsorship Head Eckhard Wannieck Talks About Company's Sports Sponsorships". www.sportsbusinessdaily.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW extends sponsorship of BMW Championship". www.pgatour.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Sponsors". www.pgatour.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Who Does What: Automobile Manufacturers". www.sponsorship.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "A Slow And Steady Course: Inside BMW's Sponsorship Strategy". www.sponsorship.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW extends sponsorship of Wentworth PGA event". Sportbusiness.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ↑ "BMW named new Springbok sponsor". www.supersport.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW SA drops the Springboks". www.wheels24.co.za. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ "Brain Bar: Dangerous ideas welcome". www.brainbar.com.

- ↑ "Performance Track Final Progress Report" (PDF). EPA. May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ↑ Sauer, Paul. "Ultimate Factories". Facts: BMW. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ "BMW Group once again sector leader in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. World's most sustainable automotive company in 2016". www.automotiveworld.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Group once again sector leader in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. World's most sustainable automotive company in 2016". www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Group once again sector leader in Dow Jones Sustainability Index". bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- ↑ https://www.wbcsd.org/Overview/Our-members/Members/BMW-AG

- ↑ "Carbon Disclosure Project Reveals Global Top 10; Apple and Amazon Don't Respond". www.environmentalleader.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Carbon Disclosure Project recognises BMW Group for the exemplary transparency of its climate protection activities - Number One Automotive Manufacturer in the CDP Global 500 ranking". www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ BMW Group (16 May 2014). "BMW Group : Sustainable Value Report 2012 : Sustainability management". bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

- ↑ Bird, J and Walker, M: "BMW A Sustainable Future? ", page 11. Wild World 2005

- ↑ "BMW Online Shop". Shop.bmwgroup.com. 21 March 2009. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "Specialized for BMW". www.bmw.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Cruise e-Bike NBG III". www.bmw.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "About DriveNow Car Sharing from BMW & Sixt". www.drive-now.com.

- ↑ "BMW Group takes top prize at the 2012 Corporate Entrepreneur Awards for premium car-sharing joint venture DriveNow. Jury impressed by willingness to trial new models of mobility". Electricdrive.org. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ ReachNow official website. "ReachNow | CarSharing by BMW, BMW i, MINI Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.." 8 May 2016.

- ↑ "BMW Group assembles first car in Brazil". press.bmwgroup.com. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 "BMW: Global growth". www.automotivemanufacturingsolutions.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Brazil to export X1 SUVs to US". www.just-auto.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "The Otto's Story". www.bmwottos.ca. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "In photos: The evolution and history of BMW as it turns 100". www.theglobeandmail.com. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "History of BMW Canada". www.bmwlondon.ca. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ General Overview Archived 19 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Brilliance Auto Official Site

- ↑ "BMW opens China factory". Testdriven.co.uk. 21 May 2004. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ Brands and Products – BMW Sedan Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Brilliance Auto Official Site

- ↑ Interone Worldwide GmbH (11 December 2006). "International BMW website". Bmw.in. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "About BMW Japan Corp". www.bmwcareer.jp. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "Joining rivals, BMW to set up $1bn plant in Mexico". Mexico Star. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ "Corporate Information: History". BMW South Africa. Archived from the original on 25 April 2007.

- ↑ "BMW South Africa – Plant Rosslyn". Bmwplant.co.za. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ "Isetta 300 model selection". www.realoem.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Company - History". www.bmwgroup.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "This is how BMW became the top selling luxury car company in the U.S." www.fortune.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "Sales by Manufacturer". www.edmunds.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Plant Spartanburg leads U.S. auto exports". Roundel. BMW Car Club of America: 30. April 2015. ISSN 0889-3225.

- ↑ "Production Overview | BMW US Factory". www.bmwusfactory.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "BMW to build 1 billion euro car factory in Hungary". U.S. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ↑ "The Stories Behind 10 of the Most Iconic Brand Slogans". www.highsnobiety.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ↑ "Can Lutz repeat his BMW marketing magic at GM?". www.autonews.com. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ↑ "BMW Still the Ultimate Driving Machine". Forbes.com. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ April Fool! A round up of the best (and worst) hoaxes Archived 18 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine., The Guardian, 1 April 2010

Further reading

- Grunert, Manfred; Triebe, Florian (2006), BMW Group Mobile Tradition, ed. (in German), Das Unternehmen BMW seit 1916, München: BMW Group Mobile Tradition, ISBN 978-3-932169-46-5

- Kiles, David (2004) (in German), Driven: Inside BMW, the Most Admired Car Company in the World, Wiley, pp. 328, ISBN 978-0-471-26920-5

- Schrader, Halwart (2004) (in German), Typenkompass BMW, Stuttgart: Motorbuch, ISBN 3-613-02386-5

- Werner, Constanze (2006) (in German), Kriegswirtschaft und Zwangsarbeit bei BMW, München: Oldenbourg, ISBN 978-3-486-57792-1

- Noakes, Andrew (in German), BMW. Vom 328 Roadster und der Isetta bis zum 5er Gran Turismo, Bath: Parragon Books, ISBN 978-1-4075-6814-0

- Schrader, Halwart (2011) (in German), BMW. Passion – Power – Perfektion., Stuttgart: Motorbuch-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-613-03378-8

.svg.png)