BMW E9

| BMW E9 | |

|---|---|

BMW 3.0 CS | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | BMW (coachbuilt by Karmann) |

| Also called | New Six Coupé |

| Production | 1968-1975 |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Grand tourer |

| Layout | FR layout |

| Body style(s) | Coupé |

| Vehicles |

2800 CS 3.0 CS 3.0 CSi 3.0 CSL 2.5 CS |

| Related |

2000 C, 2000 CS, E3 sedans |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine(s) |

M30 straight-6 engines: 2.5 L twin carb (2.5 CS) 2.8 L twin carb (2800 CS) 3.0 L twin carb (3.0 CS) 3.0 L fuel injection (3.0 CSi, 1971-1973 3.0 CSL) 3.2 L fuel injection (1973-1975 3.0 CSL) |

| Transmission(s) |

4 speed manual 3 speed automatic |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 2,624 mm (103 in) |

| Length | 4,660 mm (183 in) |

| Width | 1,670 mm (66 in) |

| Height | 1,370 mm (54 in) |

| Curb weight | 1,420 kg (3,131 lb) |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | BMW 2000C, BMW 2000CS |

| Successor | BMW 6 Series (E24) |

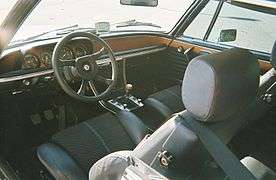

The BMW New Six CS (internal name BMW E9) is a two-door coupé built for BMW by Karmann from 1968 to 1975. It was developed from the New Class-based BMW 2000 CS coupé, which was enlarged to hold the BMW M30 straight-6 engine used in the E3 sedan.

The E9 platform, especially the 3.0 CSL homologation special, was very successful in racing, especially in European Touring Car Championship and the Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft. This helped to establish BMW's status as a sporty driver's car.

Origin: 2000 C and 2000 CS

The BMW 2000C and 2000 CS were introduced In 1965. Based on the New Class, the 2000 C and CS were Karmann-built coupés featuring the then-new two litre version of the M10 engine.[1] The 2000 C had a single carburettor engine that produced 100 hp (75 kW), and was available with either manual or automatic transmission, while the 2000 CS had a two carburettor engine that produced 120 hp (89 kW) and was available only with a manual transmission.[1][2]

2800 CS

The first of the E9 coupés, the 2800 CS, replaced the 2000 C and 2000 CS in 1968. The wheelbase and length were increased to allow the engine bay to be long enough to accommodate the new straight-six engine code-named M30, and the front of the car was restyled to resemble the E3 sedan.[3] The rear axle, however, remained the same as that used in the lesser "Neue Klasse" models and the rear brakes were initially drums - meaning that the 2800 saloon was a better performing car, as it was also lighter. The CS' advantages were thus strictly optical to begin with.[4] The 2800 CS used the 2,788 cc (170.1 cu in) version of the engine used in the E3 sedans.[3] The engine produced 170 hp (127 kW) at 6000 rpm.[5]

Not only was the 2800 CS lighter than the preceding 2000 CS, it also had a smaller frontal aspect, further increasing the performance advantage.[6]

At the 1969 Geneva Motor Show, BMW unveiled the "2800 Bertone Spicup" concept car.[7] This model, which has a similar appearance to the 1967 Alfa Romeo Montreal, did not reach production.

3.0 CS/CSi

The 2800CS was replaced by the 3.0 CS and 3.0 CSi in 1971. The engine had been bored out to give a displacement of 2,986 cc (182.2 cu in), and was offered with a 9.0:1 compression ratio, twin carburetors, and 180 hp (134 kW) at 6000 rpm in the 3.0 CS or a 9.5:1 compression ratio, Bosch D-Jetronic Electronic fuel injection, and 200 hp (149 kW) at 5500 rpm in the 3.0 CSi.[3] There was a 4 speed manual and an automatic transmission variant.

They were sold in the United States from 1970 to 1974, by Max Hoffman. He was the importer and sole distributor for BMW from the mid-sixties until selling his business to BMW of North America in 1975.[8] 1974 model cars had protruding 5 mile per hour bumpers.

3.0 CSL

- BMW 3.0 CSL

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Introduced in May 1972,[9] the 3.0 CSL was a homologation special built to make the car eligible for racing in the European Touring Car Championship. 1,265 were built.

The "L" in the designation meant leicht (light), unlike in other BMW designations, where it meant lang (long). The lightness was achieved by using thinner steel to build the unit body, deleting the trim and soundproofing,[10] using aluminium alloy doors, bonnet, and boot lid, and using Perspex side windows.[9] The five hundred 3.0 CSLs exported to the United Kingdom were not quite as light as the others, as the importer had insisted on retaining the soundproofing, electric windows, and stock E9 bumpers on these cars.[9][11] The CSL was never sold in the United States.

Initially using the same engine as the 3.0 CS,[12] the 3.0 CSL was given a very small increase in displacement to 3,003 cc (183.3 cu in) by increasing the engine bore by one quarter of a millimetre to 89.25 mm (3.51 in).[9][12] This was done in August 1972 to allow the CSL to be raced in the "over three litre" racing category, allowing for some increase in displacement in the racing cars.[9] In 1973,[10][13] the engine in the 3.0 CSL was given another, more substantial increase in displacement to 3,153 cc (3.2 L; 192.4 cu in) by increasing the stroke to 84 mm (3.31 in), rated at 206 PS (203 hp; 152 kW) at 5600 rpm and 286 N⋅m (211 lb⋅ft) at 4200 rpm of torque [12][13] [14]. This final version of the 3.0 CSL was homologated in July 1973 along with an aerodynamic package including a large air dam, short fins running along the front fenders, a spoiler above and behind the trailing edge of the roof, and a tall rear wing.[15] The rear wings were not installed at the factory, but were left in the boot for installation after purchase. This was done because the wings were illegal for use on German roads. The full aero package earned the racing CSLs the nickname "Batmobile".[10][16][17]

.jpg)

In 1973, Toine Hezemans won the European Touring Car Championship in a 3.0 CSL and co-drove a 3.0 CSL with Dieter Quester to a class victory at Le Mans. Hezemans and Quester had driven to second place at the 1973 German Touring Car Grand Prix at Nürburgring, being beaten only by Chris Amon and Hans-Joachim Stuck in another 3.0 CSL.[18] 3.0 CSLs would win the European Touring Car Championship again in every year from 1975 to 1979.[19][20]

The 3.0 CSL was raced in the IMSA GT Championship in 1975, with Sam Posey, Brian Redman, and Ronnie Peterson winning races during the season.[18]

The first two BMW Art Cars were 3.0 CSLs; the first was painted by Alexander Calder and the second by Frank Stella.[21]

The 3.5 CSL was built for Group 5 racing and BMW won three races in the 1976 World Championship for Makes with this model.

2.5 CS

The last version of the E9 to be introduced was the 2.5 CS in 1974. This was a response to the 1973 oil crisis, such that the buyer could choose the smaller, more economical engine.[22] The engine, from the 2500 sedan, displaced 2,494 cc (152.2 cu in) and produced 150 hp (112 kW) at 6000 rpm.[5] Only 874 were made until the end of E9 production in 1975, and none were exported to the United States.[22]

[23]</ref></ref>==Production Numbers==

| Model/Year | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2800 CS | 138 | 2534 | 3335 | 276 | 6283 | ||||

| 2800 CSA | 787 | 1089 | 73 | 1949 | |||||

| 3.0 CS | 1974 | 1172 | 779 | 267 | 263 | 4455 | |||

| 3.0 CSA (LHD&RHD) | 520 | 1215 | 1169 | 355 | 408 | 3667 | |||

| 3.0 CSi(LHD&RHD) | 1061 | 2999 | 2741 | 579 | 555 | 7935 | |||

| 3.0 CSiA | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 3.0 CSi RHD | 66 | 128 | 13 | 207 | |||||

| 3.0 CSA RHD | 69 | 139 | 7 | 215 | |||||

| 3.0 CSL | 169 | 252 | 287 | 40 | 17 | 765 | |||

| 3.0 CSL RHD | 349 | 151 | 500 | ||||||

| 2.5 CS | 272 | 328 | 600 | ||||||

| 2.5 CSA | 101 | 143 | 244 | ||||||

| 2800 CS USA | 43 | 415 | 183 | 641 | |||||

| 2800 CSA USA | 36 | 403 | 87 | 526 | |||||

| 3.0 CS USA | 132 | 411 | 450 | 375 | 1368 | ||||

| 3.0 CSA USA | 60 | 377 | 314 | 438 | 1189 | ||||

| Total E9 Production | 138 | 3400 | 5242 | 4535 | 6777 | 6026 | 2694 | 1734 | 30,546 |

2015 3.0 CSL Hommage

In 2015, BMW introduced the 3.0 CSL Hommage concept car at the Concorso d'Eleganza Villa d'Este. The car is a tribute to the 3.0 CSL. It has an inline-six engine with an eBoost hybrid system in the rear of the car. As a homage to the original, the 3.0 CSL Hommage has a minimal interior to keep the weight as low as possible; carbon fibre and aluminium are used in the cockpit for the same reason. The Hommage has Laser-LED lights similar to those in the i8.[25]

Notes

- 1 2 Noakes 2005, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Norbye 1984, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 Norbye 1984, p. 168.

- ↑ Becker 1971, p. 76.

- 1 2 Norbye 1984, p. 167.

- ↑ Becker 1971, p. 74.

- ↑ "Rare BMW concepts from the sixties". www.bimmerin.net. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ http://www.e9coupe.com/faq-general.htm e9coupe.com/ Retrieved May 1, 2016

- 1 2 3 4 5 Noakes 2005, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 Vaughan 2011.

- ↑ Donaldson.

- 1 2 3 Norbye 1984, p. 171.

- 1 2 Noakes 2005, p. 86.

- ↑ "1973 BMW 3.0 CSL E9 specifications". carfolio.com. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ Noakes 2005, p. 89.

- ↑ Severson 2008.

- ↑ Noakes 2005, p. 93.

- 1 2 Norbye 1984, p. 180.

- ↑ de Jong 2009.

- ↑ de Jong 2009b.

- ↑ Preece 2009.

- 1 2 Norbye 1984, p. 170.

- ↑ <ref><ref>

- ↑ "E9 Production by Year". e9-Driven.com. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- ↑ "BMW 3.0 CSL Hommage presta tributo a lenda de 1972". Retrieved 2015-05-25.

References

- Becker, Clauspeter (1971), Logoz, Arthur, ed., "BMW 2500/2800", Auto-Universum 1971 (in German), Zürich, Switzerland: Verlag Internationale Automobil-Parade AG, XIV: 76

- Donaldson, Jessica. "1973 BMW 3.0 CS news, pictures, and information". Conceptcarz - From Concept to Production. Daniel Vaughan. Retrieved 2010-07-25.

- de Jong, Frank (2009). "Part 3: 1970-1975 The Ford and BMW years". History of the European Touring Car Championship & Other International Touring Car Races. Amsterdam: Frank de Jong. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-25.

- de Jong, Frank (2009b). "Part 4: 1976-1981 The dull years". History of the European Touring Car Championship & Other International Touring Car Races. Amsterdam: Frank de Jong. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-25.

- Noakes, Andrew (2005). The Ultimate History of BMW. Bath, UK: Parragon Publishing. ISBN 1-4054-5316-8.

- Norbye, Jan P. (1984). BMW - Bavaria's Driving Machines. Skokie, IL: Publications International. ISBN 0-517-42464-9.

- Severson, Aaron (17 November 2008). "From Bavaria with Love: The BMW E9 Coupes". Ate Up With Motor - Snapshots of Automotive History. Aaron Severson. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- Vaughan, Daniel (October 2011). "1973 BMW 3.0 CSL news, pictures, and information". Conceptcarz - From Concept to Production. Daniel Vaughan. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- Preece, R. J. (10 June 2009). "Communicating BMW Art Cars: Interview with Thomas Girst". ADP/Sculpture. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

External links

« previous — BMW cars: 1960s to 1980s — next » | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 3 Series | 02 Series | E21 | E30 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 Series | New Class sedans | E12 | E28 | E34>> | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 Series | 3200 CS | 2000 C, 2000 CS | E9 | E24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 Series | <<501, 502 | E3 | E23 | E32>> | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 Series | E31>> | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isetta | <<Isetta 250, Isetta 300 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 700 | LS, 700 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 507, Z1 | 507 | Z1>> | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1600GT | 1600GT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M1 | E26 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||