Almond

| Almond | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1897 illustration[1] | |

| |

| Almond tree with ripening fruit. Majorca, Spain | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Prunus |

| Subgenus: | Prunus subg. Amygdalus |

| Species: | P. dulcis |

| Binomial name | |

| Prunus dulcis | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

The almond (Prunus dulcis, syn. Prunus amygdalus) is a species of tree native to Mediterranean climate regions of the Middle East, from Syria and Turkey to India and Pakistan, although it has been introduced elsewhere.[3]

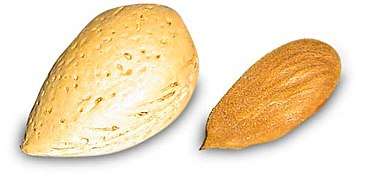

Almond is also the name of the edible and widely cultivated seed of this tree. Within the genus Prunus, it is classified with the peach in the subgenus Amygdalus, distinguished from the other subgenera by corrugations on the shell (endocarp) surrounding the seed.

The fruit of the almond is a drupe, consisting of an outer hull and a hard shell with the seed, which is not a true nut, inside. Shelling almonds refers to removing the shell to reveal the seed. Almonds are sold shelled or unshelled. Blanched almonds are shelled almonds that have been treated with hot water to soften the seedcoat, which is then removed to reveal the white embryo.

Description

Tree

The almond is a deciduous tree, growing 4–10 m (13–33 ft) in height, with a trunk of up to 30 cm (12 in) in diameter. The young twigs are green at first, becoming purplish where exposed to sunlight, then grey in their second year. The leaves are 8–13 cm (3–5 in) long,[4] with a serrated margin and a 2.5 cm (1 in) petiole. The flowers are white to pale pink, 3–5 cm (1–2 in) diameter with five petals, produced singly or in pairs and appearing before the leaves in early spring.[5][6] Almond grows best in Mediterranean climates with warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters. The optimal temperature for their growth is between 15 and 30 °C (59 and 86 °F) and the tree buds have a chilling requirement of 300 to 600 hours below 7.2 °C (45.0 °F) to break dormancy.[7]

Almonds begin bearing an economic crop in the third year after planting. Trees reach full bearing five to six years after planting. The fruit matures in the autumn, 7–8 months after flowering.[6][8]

Drupe

.jpg)

The almond fruit measures 3.5–6 cm (1 3⁄8–2 3⁄8 in) long. In botanical terms, it is not a nut but a drupe. The outer covering or exocarp, fleshy in other members of Prunus such as the plum and cherry, is instead a thick, leathery, grey-green coat (with a downy exterior), called the hull. Inside the hull is a reticulated, hard, woody shell (like the outside of a peach pit) called the endocarp. Inside the shell is the edible seed, commonly called a nut. Generally, one seed is present, but occasionally two occur. After the fruit matures, the hull splits and separates from the shell, and an abscission layer forms between the stem and the fruit so that the fruit can fall from the tree.[9]

Green almonds

Green almonds Almond in shell and shelled

Almond in shell and shelled Blanched almonds

Blanched almonds- Shelled Almond

- Almond confections

Origin and history

The almond is native to the Mediterranean climate region of the Middle East, from Syria and Turkey eastward to Pakistan and India.[3] It was spread by humans in ancient times along the shores of the Mediterranean into northern Africa and southern Europe, and more recently transported to other parts of the world, notably California, United States.[3] The wild form of domesticated almond grows in parts of the Levant.[11]

Selection of the sweet type from the many bitter types in the wild marked the beginning of almond domestication.[12] It is unclear as to which wild ancestor of the almond created the domesticated species. The species Prunus fenzliana may be the most likely wild ancestor of the almond in part because it is native of Armenia and western Azerbaijan where it was apparently domesticated. Wild almond species were grown by early farmers, "at first unintentionally in the garbage heaps, and later intentionally in their orchards".[13]

Almonds were one of the earliest domesticated fruit trees due to "the ability of the grower to raise attractive almonds from seed. Thus, in spite of the fact that this plant does not lend itself to propagation from suckers or from cuttings, it could have been domesticated even before the introduction of grafting".[11] Domesticated almonds appear in the Early Bronze Age (3000–2000 BC) such as the archaeological sites of Numeria (Jordan),[12] or possibly earlier. Another well-known archaeological example of the almond is the fruit found in Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt (c. 1325 BC), probably imported from the Levant.[11] Of the European countries that the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh reported as cultivating almonds, Germany[14] is the northernmost, though the domesticated form can be found as far north as Iceland.[15]

Etymology and names

The word "almond" comes from Old French almande or alemande, Late Latin *amandula, derived through a form amygdala from the Greek ἀμυγδάλη (amygdálē) (cf. amygdala), an almond.[16] The al- in English, for the a- used in other languages may be due a confusion with the Arabic article al, the word having first dropped the a- as in the Italian form mandorla; the British pronunciation ah-mond and the modern Catalan ametlla and modern French amande show a form of the word closer to the original. Other related names of almond include mandel or knackmandel (German), mandorlo (Italian for the tree), mandorla (Italian for the fruit), amêndoa (Portuguese), and almendra (Spanish).[17]

The adjective "amygdaloid" (literally "like an almond") is used to describe objects which are roughly almond-shaped, particularly a shape which is part way between a triangle and an ellipse. See, for example, the brain structure amygdala, which uses a direct borrowing of the Greek term amygdalē.[18]

Cultivation

Pollination

The pollination of California's almonds is the largest annual managed pollination event in the world, with close to one million hives (nearly half of all beehives in the US) being trucked in February to the almond groves. Much of the pollination is managed by pollination brokers, who contract with migratory beekeepers from at least 49 states for the event. This business has been heavily affected by colony collapse disorder, causing nationwide shortages of honey bees and increasing the price of insect pollination. To partially protect almond growers from the rising cost of insect pollination, researchers at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) have developed a new line of self-pollinating almond trees.[19] Self-pollinating almond trees, such as the 'Tuono', have been around for a while, but their harvest is not as desirable as the insect-pollinated California 'Nonpareil' almond tree. The 'Nonpareil' tree produces large, smooth almonds and offers 60–65% edible kernel per nut. The Tuono has thicker, hairier shells and offers only 32% of edible kernel per nut, but having a thick shell has advantages. The Tuono's shell protects the nut from threatening pests such as the navel orangeworm. ARS researchers have managed to crossbreed the pest-resistant Tuono tree with the 'Nonpareil, resulting in hybridized cultivars of almond trees that are self-pollinated and maintain a high nut quality.[19] The new, self-pollinating hybrids possess quality skin color, flavor, and oil content, and reduce almond growers' dependency on insect pollination.[19]

A grove of almond trees in central California

A grove of almond trees in central California- Almond blossoms in Iran

- Young almond fruit

_(cropped).jpg) Mature almond fruit

Mature almond fruit

Diseases

Almond trees can be attacked by an array of damaging organisms, including insects, fungal pathogens, plant viruses, and bacteria.[20]

Production

| Almonds (with shell) Production in 2016 | |

|---|---|

| Country | tonnes |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[21] | |

In 2016, world production of almonds was 3.2 million tonnes, with United States providing 63% of the total.[21] As other leading producers, Spain, Iran, and Morocco combined contributed 14% of the world total (table).

United States

In the United States, production is concentrated in California where 1,000,000 acres (400,000 ha) and six different almond varieties were under cultivation in 2017, with a yield of 2.25 billion lb (1.02 billion kg) of shelled almonds.[22] California production is marked by a period of intense pollination during late winter by rented commercial bees transported by truck across the United States to almond groves, requiring more than half of the total US honeybee population.[23] The value of total US exports of shelled almonds in 2016 was $3.2 billion.[24]

Spain

Spain has diverse commercial cultivars of almonds grown in Catalonia, Valencia, Murcia, Andalusia, and Aragón regions, and the Balearic Islands.[25] Production in 2016 declined 2% nationally compared to 2015 production data.[25]

Australia

Australia is the largest almond production region in the Southern Hemisphere. Most of the almond orchards are located along the Murray River corridor in New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia.[26][27]

Sweet and bitter almonds

The seeds of Prunus dulcis var. dulcis are predominantly sweet[28][29] but some individual trees produce seeds that are somewhat more bitter. The genetic basis for bitterness involves a single gene, the bitter flavor furthermore being recessive,[30][31] both aspects making this trait easier to domesticate. The fruits from Prunus dulcis var. amara are always bitter, as are the kernels from other species of genus Prunus, such as peach and cherry (although to a lesser extent).

The bitter almond is slightly broader and shorter than the sweet almond and contains about 50% of the fixed oil that occurs in sweet almonds. It also contains the enzyme emulsin which, in the presence of water, acts on the two soluble glucosides amygdalin and prunasin[32] yielding glucose, cyanide and the essential oil of bitter almonds, which is nearly pure benzaldehyde, the chemical causing the bitter flavor. Bitter almonds may yield 4–9 mg of hydrogen cyanide per almond[33] and contain 42 times higher amounts of cyanide than the trace levels found in sweet almonds.[34] The origin of cyanide content in bitter almonds is via the enzymatic hydrolysis of amygdalin.[34]

Extract of bitter almond was once used medicinally but even in small doses, effects are severe or lethal, especially in children; the cyanide must be removed before consumption.[34] The acute oral lethal dose of cyanide for adult humans is reported to be 0.5–3.5 mg/kg (0.2–1.6 mg/lb) of body weight (approximately 50 bitter almonds), whereas for children, consuming 5–10 bitter almonds may be fatal.[34]

All commercially grown almonds sold as food in the United States are sweet cultivars. The US Food and Drug Administration reported in 2010 that some fractions of imported sweet almonds were contaminated with bitter almonds. Eating such almonds could result in vertigo and other typical bitter almond (cyanide) poisoning effects.[35]

Culinary uses

While the almond is often eaten on its own, raw or toasted, it is also a component of various dishes. Almonds are available in many forms, such as whole, sliced (flaked, slivered), and as flour. Almonds yield almond oil and can also be made into almond butter or almond milk. These products can be used in both sweet and savoury dishes.

Along with other nuts, almonds can be sprinkled over breakfasts and desserts, particularly muesli or ice cream-based dishes. Almonds are used in marzipan, nougat, many pastries (including jesuites), cookies (including French macarons, macaroons), and cakes (including financiers), noghl, and other sweets and desserts. They are also used to make almond butter, a spread similar to peanut butter, popular with peanut allergy sufferers and for its naturally sweeter taste. The young, developing fruit of the almond tree can be eaten whole (green almonds) when they are still green and fleshy on the outside and the inner shell has not yet hardened. The fruit is somewhat sour, but is a popular snack in parts of the Middle East, eaten dipped in salt to balance the sour taste. Also in the Middle East they are often eaten with dates. They are available only from mid-April to mid-June in the Northern Hemisphere; pickling or brining extends the fruit's shelf life.

Almond cookies, Chinese almond biscuits, and Italian ricciarelli are made with almonds.

- In Greece, ground blanched almonds are used as the base material in a great variety of desserts, usually called amygdalota (αμυγδαλωτά). Because of their white color, most are traditionally considered wedding sweets and are served at wedding banquets. In addition, a soft drink known as soumada is made from almonds in various regions.

- In Hejaz, a region of Saudi Arabia, ground almonds are used by adding them with cold milk to a hot coffee cup in addition to cinnamon powder and corn starch to make Almond Coffee Gahwat Al-lōz (قهوة اللوز).

- In Iran, green almonds are dipped in sea salt and eaten as snacks on street markets; they are called chaqale bâdam. Also sweet almonds are used to prepare a special food for babies, named harire badam. Almonds are added to some foods, cookies, and desserts, or are used to decorate foods. People in Iran consume roasted nuts for special events, for example, during New Year (Nowruz) parties.

- In Italy, bitter almonds are the traditional base for amaretti[36][37] (almond macaroons), a common dessert. Traditionally, a low percentage of bitter almonds (10–20%) is added to the ingredients, which gives the cookies their bitter taste (commercially, apricot kernels are used as a substitute for bitter almonds). Almonds are also a common choice as the nuts to include in torrone. In Apulia and Sicily, pasta di mandorle (almond paste) is used to make small soft cakes, often decorated with jam, pistachio, or chocolate. In Sicily, almond milk is a popular refreshing beverage in summer.

- In Morocco, almonds in the form of sweet almond paste are the main ingredient in pastry fillings, and several other desserts. Fried blanched whole almonds are also used to decorate sweet tajines such as lamb with prunes. A drink made from almonds mixed with milk is served in important ceremonies such as weddings and can also be ordered in some cafes. Southwestern Berber regions of Essaouira and Souss are also known for amlou, a spread made of almond paste, argan oil, and honey. Almond paste is also mixed with toasted flour and among others, honey, olive oil or butter, anise, fennel, sesame seeds, and cinnamon to make sellou (also called zamita in Meknes or slilou in Marrakech), a sweet snack known for its long shelf life and high nutritive value.

- In Indian cuisine, almonds are the base ingredients of pasanda-style and Mughlai curries. Badam halva is a sweet made from almonds with added coloring. Almond flakes are added to many sweets (such as sohan barfi), and are usually visible sticking to the outer surface. Almonds form the base of various drinks which are supposed to have cooling properties. Almond sherbet or sherbet-e-badaam, is a popular summer drink. Almonds are also sold as a snack with added salt.

- In Israel almonds are topping tahini cookie or eaten as a snack.

The 'Marcona' almond cultivar is recognizably different from other almonds and is marketed by name.[38] The kernel is short, round, relatively sweet, and delicate in texture. Its origin is unknown and has been grown in Spain for a long time; the tree is very productive, and the shell of the nut is very hard.[38] 'Marcona' almonds are traditionally served after being lightly fried in oil, and are used by Spanish confectioners to prepare a sweet called turrón.

Certain natural food stores sell "bitter almonds" or "apricot kernels" labeled as such, requiring significant caution by consumers for how to prepare and eat these products.[39]

Almond milk

Almonds can be processed into a milk substitute called almond milk; the nut's soft texture, mild flavor, and light coloring (when skinned) make for an efficient analog to dairy, and a soy-free choice for lactose intolerant people and vegans. Raw, blanched, and lightly toasted almonds work well for different production techniques, some of which are similar to that of soymilk and some of which use no heat, resulting in "raw milk" (see raw foodism).

Almond flour and skins

Almond flour or ground almond meal combined with sugar or honey as marzipan is often used as a gluten-free alternative to wheat flour in cooking and baking.[40]

Almonds contain polyphenols in their skins consisting of flavonols, flavan-3-ols, hydroxybenzoic acids and flavanones[41] analogous to those of certain fruits and vegetables. These phenolic compounds and almond skin prebiotic dietary fiber have commercial interest as food additives or dietary supplements.[41][42]

Almond syrup

Historically, almond syrup was an emulsion of sweet and bitter almonds, usually made with barley syrup (orgeat syrup) or in a syrup of orange flower water and sugar, often flavored with a synthetic aroma of almonds.[34]

Due to the cyanide found in bitter almonds, modern syrups generally are produced only from sweet almonds. Such syrup products do not contain significant levels of hydrocyanic acid, so are generally considered safe for human consumption.[34]

Nutrition

| |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 2,423 kJ (579 kcal) |

|

21.6 g | |

| Starch | 0.7 g |

| Sugars |

4.4 g 0.00 g |

| Dietary fiber | 12.5 g |

|

49.9 g | |

| Saturated | 3.8 g |

| Monounsaturated | 31.6 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 12.3 g |

|

21.2 g | |

| Tryptophan | 0.214 g |

| Threonine | 0.598 g |

| Isoleucine | 0.702 g |

| Leucine | 1.488 g |

| Lysine | 0.580 g |

| Methionine | 0.151 g |

| Cystine | 0.189 g |

| Phenylalanine | 1.120 g |

| Tyrosine | 0.452 g |

| Valine | 0.817 g |

| Arginine | 2.446 g |

| Histidine | 0.557 g |

| Alanine | 1.027 g |

| Aspartic acid | 2.911 g |

| Glutamic acid | 6.810 g |

| Glycine | 1.469 g |

| Proline | 1.032 g |

| Serine | 0.948 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. |

0% 1 μg1 μg |

| Vitamin A | 1 IU |

| Thiamine (B1) |

18% 0.211 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

85% 1.014 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

23% 3.385 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) |

9% 0.469 mg |

| Vitamin B6 |

11% 0.143 mg |

| Folate (B9) |

13% 50 μg |

| Choline |

11% 52.1 mg |

| Vitamin C |

0% 0 mg |

| Vitamin D |

0% 0 μg |

| Vitamin E |

171% 25.6 mg |

| Vitamin K |

0% 0.0 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium |

26% 264 mg |

| Copper |

50% 0.99 mg |

| Iron |

29% 3.72 mg |

| Magnesium |

75% 268 mg |

| Manganese |

109% 2.285 mg |

| Phosphorus |

69% 484 mg |

| Potassium |

15% 705 mg |

| Selenium |

4% 2.5 μg |

| Sodium |

0% 1 mg |

| Zinc |

32% 3.08 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 4.4 g |

|

| |

| |

|

†Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Almonds are 4% water, 22% carbohydrates, 21% protein, and 50% fat (table). In a 100 gram reference amount, almonds supply 579 calories. The almond is a nutritionally dense food (table), providing a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of the B vitamins riboflavin and niacin, vitamin E, and the essential minerals calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, and zinc. Almonds are a moderate source (10–19% DV) of the B vitamins thiamine, vitamin B6, and folate, choline, and the essential mineral potassium. They also contain substantial dietary fiber, the monounsaturated fat, oleic acid, and the polyunsaturated fat, linoleic acid. Typical of nuts and seeds, almonds are a source of phytosterols such as beta-sitosterol, stigmasterol, campesterol, sitostanol, and campestanol.[43]

Potential allergy

Almonds may cause allergy or intolerance. Cross-reactivity is common with peach allergens (lipid transfer proteins) and tree nut allergens. Symptoms range from local signs and symptoms (e.g., oral allergy syndrome, contact urticaria) to systemic signs and symptoms including anaphylaxis (e.g., urticaria, angioedema, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms).[44]

Oils

| Nutritional value per 100 g | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 3,699 kJ (884 kcal) |

|

100 g | |

| Saturated | 8.2 g |

| Monounsaturated | 69.9 g |

| Polyunsaturated |

17.4 g 0 17.4 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin E |

261% 39.2 mg |

| Vitamin K |

7% 7.0 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron |

0% 0 mg |

|

| |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Almonds are a rich source of oil, with 50% of kernel dry mass as fat (whole almond nutrition table). In relation to total dry mass of the kernel, almond oil contains 32% monounsaturated oleic acid (an omega-9 fatty acid), 13% linoleic acid (a polyunsaturated omega-6 essential fatty acid), and 10% saturated fatty acid (mainly as palmitic acid, USDA link in table). Linolenic acid, a polyunsaturated omega-3 fat, is not present (table). Almond oil is a rich source of vitamin E, providing 261% of the Daily Value per 100 ml (table).

When almond oil is analyzed separately and expressed per 100 grams as a reference mass, the oil provides 884 calories, 8 grams of saturated fat (81% of which is palmitic acid), 70 grams of oleic acid, and 17 grams of linoleic acid (oil table).

Oleum amygdalae, the fixed oil, is prepared from either sweet or bitter almonds, and is a glyceryl oleate with a slight odour and a nutty taste. It is almost insoluble in alcohol but readily soluble in chloroform or ether. Almond oil is obtained from the dried kernel of almonds.[45]

Aflatoxins

Almonds are susceptible to aflatoxin-producing molds.[46] Aflatoxins are potent carcinogenic chemicals produced by molds such as Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. The mold contamination may occur from soil, previously infested almonds, and almond pests such as navel-orange worm. High levels of mold growth typically appear as gray to black filament like growth. It is unsafe to eat mold infected tree nuts.

Some countries have strict limits on allowable levels of aflatoxin contamination of almonds and require adequate testing before the nuts can be marketed to their citizens. The European Union, for example, introduced a requirement since 2007 that all almond shipments to EU be tested for aflatoxin. If aflatoxin does not meet the strict safety regulations, the entire consignment may be reprocessed to eliminate the aflatoxin or it must be destroyed.[47][48]

Mandatory pasteurization in California

The USDA approved a proposal by the Almond Board of California to pasteurize almonds sold to the public, after tracing cases of salmonellosis to almonds. The almond pasteurization program became mandatory for California companies in 2007.[49] Raw, untreated California almonds have not been available in the U.S. since then.

California almonds labeled "raw" must be steam-pasteurized or chemically treated with propylene oxide (PPO). This does not apply to imported almonds[50] or almonds sold from the grower directly to the consumer in small quantities.[51] The treatment also is not required for raw almonds sold for export outside of North America.

The Almond Board of California states: “PPO residue dissipates after treatment.” The U.S. EPA has reported: “Propylene oxide has been detected in fumigated food products; consumption of contaminated food is another possible route of exposure.” PPO is classified as Group 2B ("possibly carcinogenic to humans").[52]

The USDA-approved marketing order was challenged in court by organic farmers organized by the Cornucopia Institute, a Wisconsin-based farm policy research group. According to the Cornucopia Institute, this almond marketing order has imposed significant financial burdens on small-scale and organic growers and damaged domestic almond markets. A federal judge dismissed the lawsuit in the spring of 2009 on procedural grounds. In August 2010, a federal appeals court ruled that the farmers have a right to appeal the USDA regulation. In March 2013, the court vacated the suit on the basis that the objections should have been raised in 2007 when the regulation was first proposed.[53]

Cultural aspects

The almond is highly revered in some cultures. The tree originated in the Middle East,[54] and is mentioned numerous times in the Bible.

In the Hebrew Bible, the almond was a symbol of watchfulness and promise due to its early flowering. In the Bible the almond is mentioned ten times, beginning with Book of Genesis 43:11, where it is described as "among the best of fruits". In Numbers 17 Levi is chosen from the other tribes of Israel by Aaron's rod, which brought forth almond flowers. According to tradition, the rod of Aaron bore sweet almonds on one side and bitter on the other; if the Israelites followed the Lord, the sweet almonds would be ripe and edible, but if they were to forsake the path of the Lord, the bitter almonds would predominate. The almond blossom supplied a model for the menorah which stood in the Holy Temple, "Three cups, shaped like almond blossoms, were on one branch, with a knob and a flower; and three cups, shaped like almond blossoms, were on the other...on the candlestick itself were four cups, shaped like almond blossoms, with its knobs and flowers" (Exodus 25:33–34; 37:19–20).

Similarly, Christian symbolism often uses almond branches as a symbol of the Virgin Birth of Jesus; paintings and icons often include almond-shaped haloes encircling the Christ Child and as a symbol of Mary. The word "Luz", which appears in Genesis 30:37, sometimes translated as "hazel", may actually be derived from the Aramaic name for almond (Luz), and is translated as such in some Bible versions such as the NIV.[55] The Arabic name for almond is لوز "lauz" or "lūz". In some parts of the Levant and North Africa it is pronounced "loz", which is very close to its Aramaic origin.

La entrada de la flor is an event celebrated on 1 February in Torrent, Spain, in which the clavarios and members of the Confrerie of the Mother of God deliver a branch of the first-blooming almond-tree to the Virgin.[56]

See also

References

- ↑ illustration from Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897

- ↑ The Plant List, Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A.Webb

- 1 2 3 Introduction to Fruit Crops (Published Online), Mark Rieger, 2006

- ↑ Bailey, L.H.; Bailey, E.Z.; the staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium. 1976. Hortus third: A concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. Macmillan, New York.

- ↑ Rushforth, Keith (1999). Collins wildlife trust guide trees: a photographic guide to the trees of Britain and Europe. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-220013-9.

- 1 2 Griffiths, Mark D.; Anthony Julian Huxley (1992). The New Royal Horticultural Society dictionary of gardening. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-47494-5.

- ↑ "Almond". PlantVillage, The Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University. 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "University of California Sample Cost Study to Produce Almonds" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ Doll, David (22 June 2009). "The Seasonal Patterns of Almond Production". The Almond Doctor. University of California Cooperative Extension. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Bhawani (1590s). "Harvesting of the almond crop at Qand-i Badam". Baburnama.

- 1 2 3 Zohary, Daniel; Maria Hopf (2000). Domestication of plants in the old world: the origin and spread of cultivated plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley. Oxford University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-19-850356-3.

- 1 2 G. Ladizinsky (1999). "On the origin of almond". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 46 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1023/A:1008690409554.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 118. ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- ↑ "Flora Europaea Search Results". Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ↑ "Prunus dulcis". Plants for a Future. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ↑ "Almond". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ Gernot Katzer (2005). "Almond (Prunus dulcis [Mill.] D. A. Webb.)". University of Graz, Austria. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012.

- ↑ Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J (1 July 2003). "The Amygdaloid Complex: Anatomy and Physiology". Physiological Reviews. 83 (3): 803–834. doi:10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. PMID 12843409. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Alfredo Flores (6 April 2010). "ARS Scientists Develop Self-pollinating Almond Trees". USDA Agricultural Research Service. Archived from the original on 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Almond Description". Plant Village. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Almonds (in shells) production in 2016, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ Averill, Travis (6 July 2017). "2017 Almond Forecast" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Service, US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ Ginger Zee; David Miller; Kelly Harold; Andrea Miller (16 January 2018). "Growing California almonds takes more than half of US honeybees". ABC News. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ↑ Workman, Daniel (25 July 2017). "Top Almonds Exporters by Country in 2016". World's Top Exports. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- 1 2 "Tree nuts annual; Almonds, shelled basis; Report number SP1619" (PDF). GAIN Report, US Department of Agriculture. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ↑ "Where are Australian Almonds grown?". Almond Board of Australia. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ↑ Gibson, Chris (5 February 2014). "Agri-comeback kids of 2014". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ↑ Karl-Franzens-Universität (Graz). "Almond (Prunus dulcis [Mill.] D. A. Webb.)". Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ "Almond and bitter almond". from Quirk Books: www.quirkbooks.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Heppner, Myer J (7 April 1923). "The factor for bitterness in the sweet almond". Genetics. 8 (4): 390–392. PMC 1200758. PMID 17246020.

- ↑ Dicenta, Federico; Ortega, Encarnacion; Martinez-Gomez, Pedro (January 2007). "Use of recessive homozygous genotypes to assess genetic control of kernel bitterness in almond". Euphytica. Springer. 153 (1–2): 221–225. doi:10.1007/s10681-006-9257-6.

- ↑ Sánchez-Pérez R, Belmonte FS, Borch J, Dicenta F, Møller BL, Jørgensen K (April 2012). "Prunasin hydrolases during fruit development in sweet and bitter almonds". Plant Physiology. 158 (4): 1916–32. doi:10.1104/pp.111.192021. PMC 3320195. PMID 22353576.

- ↑ Shragg TA, Albertson TE, Fisher CJ (January 1982). "Cyanide poisoning after bitter almond ingestion". West. J. Med. 136 (1): 65–9. PMC 1273391. PMID 7072244.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chaouali N, Gana I, Dorra A, Khelifi F, Nouioui A, Masri W, Belwaer I, Ghorbel H, Hedhili A (2013). "Potential Toxic Levels of Cyanide in Almonds (Prunus amygdalus), Apricot Kernels (Prunus armeniaca), and Almond Syrup". ISRN Toxicol. 2013 (19 September): 610648. doi:10.1155/2013/610648. PMC 3793392. PMID 24171123.

- ↑ Toomey VM, Nickum EA, Flurer CL (September 2012). "Cyanide and amygdalin as indicators of the presence of bitter almonds in imported raw almonds" (PDF). Journal of Forensic Sciences. 57 (5): 1313–7. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02138.x. PMID 22564183.

- ↑ Amaretto Macaroon. "Fine Italian Pastries & Biscotti". Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ "Vicenzi Amaretto s'Italia (Macaroona)". Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- 1 2 Gradziel, T.M. (2011). "Origin and Dissemination of Almonds". In J. Janick. Horticultural Reviews, Volume 38. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. doi:10.1002/9780470872376.ch2. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ↑ "Cyanogenic glycosides – Information Sheet" (PDF). New Zealand Food Safety Authority. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Amsterdam, Elana (2009). The Gluten-Free Almond Flour Cookbook: Breakfasts, Entrees, and More. Random House of Canada. ISBN 978-1-58761-345-6.

- 1 2 Mandalari, G.; Tomaino, A.; Arcoraci, T.; Martorana, M.; Turco, V. Lo; Cacciola, F.; Rich, G.T.; Bisignano, C.; Saija, A.; Dugo, P.; Cross, K.L.; Parker, M.L.; Waldron, K.W.; Wickham, M.S.J. (2010). "Characterization of polyphenols, lipids and dietary fibre from almond skins (Amygdalus communis L.)". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 23 (2): 166–174. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2009.08.015.

- ↑ Liu Z, Lin X, Huang G, Zhang W, Rao P, Ni L (2014). "Prebiotic effects of almonds and almond skins on intestinal microbiota in healthy adult humans". Anaerobe. 26 (4): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.11.007. PMID 24315808.

- ↑ Berryman CE, Preston AG, Karmally W, Deckelbaum RJ, Kris-Etherton PM (April 2011). "Effects of almond consumption on the reduction of LDL-cholesterol: a discussion of potential mechanisms and future research directions". Nutrition Reviews. 69 (4): 171–85. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00383.x. PMID 21457263.

- ↑ "Almond allergy on Food info". Food-info.net. 26 July 2001. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ Soler L, Canellas J, Saura-Calixto F (1988). "Oil content and fatty acid composition of developing almond seeds". J Agric Food Chem. 36 (4): 695–697. doi:10.1021/jf00082a007.

- ↑ "The high cost of aflatoxins" (PDF). Almond Board of California. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2013.

- ↑ "Aflatoxins in food". European Food Safety Authority. 2010.

- ↑ "New EU Aflatoxin Levels and Sampling Plan" (PDF). USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2011.

- ↑ "The Food Safety Program & Almond Pasteurization" (Press release). Almond Board of California. 17 September 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ↑ Agricultural Marketing Service (8 November 2006) "Almonds Grown in California: Changes to Incoming Quality Control Requirements" (71 FR -FR-65373 65373, 71 FR -FR-65374 65374, 71 FR -FR-65375 65375 and 71 FR -FR-65376 65376)

- ↑ Burke, Garance (29 June 2007). "Almond pasteurization rubs some feelings raw". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ↑ Harris LJ, ed. (2013). Improving the Safety and Quality of Nuts. Elsevier, Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0857097482. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017.

- ↑ "The Authentic Almond Project". The Cornucopia Institute. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Tubeileh A, Bruggeman A, Turkelboom F (2004). Growing Olives and Other Tree Species in Marginal Arid Environments (PDF). ICARDA.

- ↑ Fred Hageneder. The meaning of trees: botany, history, healing, lore. p. 37. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Sena, Laura (2 February 2016). "Fuego y flor de almendro en l'Entrà de Torrent". www.levante-emv.com. Levante. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Almonds (Prunus dulcis). |

| Wikispecies has information related to Prunus dulcis |