Xaidulla

| Xaidulla Shahidulla | |

|---|---|

| Historic village & campground | |

Xaidulla | |

| Coordinates: 36°24′49″N 77°59′17″E / 36.41361°N 77.98806°ECoordinates: 36°24′49″N 77°59′17″E / 36.41361°N 77.98806°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Xinjiang |

| County | Pishan |

| Elevation[1] | 3,700 m (12,100 ft) |

| Xaidulla | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 賽圖拉 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赛图拉 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||

| Uyghur |

شەيدۇللا Shahidulla Шаһидулла | ||||||||

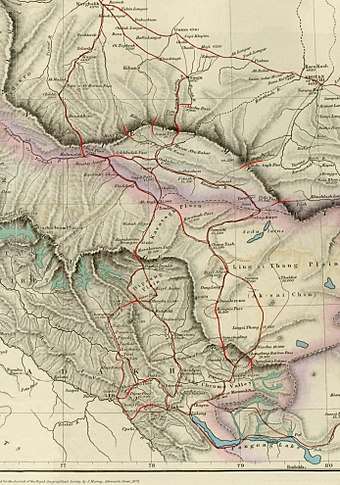

Xaidulla, also spelled Shahidullah or Shahidula (altitude ca. 3,646 m or 11,962 ft), or Saitula in Chinese, is a town in Pishan County in the southwestern part of Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China. It is strategically located on the upper Karakash River, just to the north of the Karakoram Pass on the old caravan route between the Tarim Basin and Ladakh. It lies next to the Chinese National Highway G219 between Kashgar and Tibet, 25 km east of Mazar and 115 km west of Dahongliutan.

Geography and trade

Shahidulla is situated between the Kunlun mountains and the Karakoram range, "close to the southern foot of the former".[2] It is on the bank of the Karakash River, which originates in the Aksai Chin plains, flows northeast and makes a sharp bend to the west at the foot of the Kunlun range. After making another bend at Shahidullah, it flows northwest again, cutting through the Kunlun mountains towards Khotan.

Travellers talk about a "southern branch" of the Kunlun range at the foot of which the Karakash flows, and a "northern branch" (also called the "Kilian range") which has various passes (from the west to east, Yangi, Kilik, Kilian, Sanju, Hindu-tagh and Ilchi passes). The Kilian and Sanju passes are the most often mentioned, which lead to Kashgar. To the south of Shahidulla, the trade route passed through Suget Pass and, after crossing the Yarkand River at Ak-tagh, through the Karakoram Pass into Ladakh. An alternative route to Ladakh from Shahidulla went along the Karakash river till reaching the Aksai Chin plains and then to Ladakh. This route was only feasible for large traders. The Aksai Chin being desolate and barren, they had to carry fodder for the pack animals along with their cargo.

The entire area between between the Karakoram range and the Kunlun mountains is uninhabited and has very little vegetation, except for the river valleys of Yarkand and Karakash. In these valleys, during the summer months, cultivation was possible. Kanjutis from Hunza used to cultivate in the Yarkand valley (called "Raskam" plots) and the Kirghiz from Turkestan used to cultivate in the area of Shahidullah. Shahidullah is described as a "seasonal township" in the sources, but it was little more than a campground in the 19th century.[3]

What it lacked in habitation was made up by brusque trade. Kulbhushan Warikoo states that the trade between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent passed through two routes: one in the west, through Chitral and the Pamirs, and the other in the east, through Shahidullah and Ladakh. The eastern route is said to have been more favoured by the traders as it was relatively safe from robberies and political turmoil.

Such was the safety of this route that in the event of unfavourable weather or death of ponies, traders would march to a safe place leaving behind their goods which were fetched after the climate became favourable or substitute transport became available.[4]

The absence of turmoil was not a given. In fact, the traders applied pressure on the rulers to avoid conflict. The Ladakhis especially heeded such warnings, dependent as they were on trade for their prosperity.[5]

History

There is legendary and documentary evidence that indicates that Indians from Taxila and the Chinese were among the first settlers of Khotan. In the first century BC, Kashmir and Khotan on the two sides of the Karakoram range formed a joint kingdom, which was ruled by either Scythian or Turki (Elighur) chiefs. Towards the end of the first century AD, the kingdom broke up into two parts: Khotan being annexed by the Chinese and Kashmir by Kanishka.[6]

Early records

Edouard Chavannes tentatively identified Zihe (W-G: Tzu-ho) as Kargilik[7], and several later authors have followed this identification. However, Aurel Stein made a strong case that it was, instead, located to the south of Kargilik: "Both the distance indicated and the situation in a confined valley point to one or another of the submontane oases south of Karghalik as the Tzŭ-ho capital here referred to."[8].

Of these "submontane oases south of Karghalik," Xaidulla was the most important, being at a key fork in the road, which heads south towards northern India, or west towards the Tashkurgan valley, Wakhan, and from there south to northern Pakistan, or west into Badakshan.

Part of the reason for the confusion in identifying these early 'kingdoms" is that, according to the Hanshu, the King of both Hsi-yeh and Tzuho were ruled by the "king of Tzu-ho."[9], but the later Hou Hanshu states: "“The Hanshu wrongly stated that Xiye [Karghalik] and Zihe formed one kingdom. Each now has its own king.” The other reason is that Stein made an incorrect estimation of the Han li as being approximately one fifth of a mile (about 322 metres)[10] instead of the now generally accepted 415.8 metres.[11]

However, both accounts give exactly the same population figures, in the Hou Hanshu were simply copied from those given in the Hanshu, and probably originally referred to the combined population of both small kingdoms.

Although this region clearly must have remained a welcome stop-over for caravans on the important branch route from the Tarim Basin to Ladakh and India, there are few, if any, further written records of it until the British merchant, Robert Shaw, reached it.[12]

19th century

The Dogra ruler, Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, acting under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire in Lahore, conquered Ladakh in 1834.[13] The primary driver in the conquest was the control the trade that passed through Ladakh. The Dogra general Zorawar Singh immediately wanted to invade the Chinese Turkestan. Alarmed by this development, the British put pressure on him via Lahore to desist.[14] However, all the area up to Shahidulla was taken control of by the Dogras, as the Chinese Turkestan then viewed the Kunlun mountains as its southern border.[15] In 1846, the Sikhs gave up Raja Gulab Singh and his domains to the British, who then established him as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir under their suzerainty. Thus began a long tug-of-war between the Dogras and British regarding the control over Shahidulla, and in fact the entire tract lying between the Karakoram range and the Kunlun mountains.[16]

The British were inclined to view the Karakoram range as the natural boundary of the Indian subcontinent as it defined a water-parting line, south of which waters flowed into the Indus River and the Arabian Sea and north of which the waters flowed into the Tarim Basin. However, the Turkestanis viewed the northern branch of the Kunlun mountains (sometimes called the "Kilian range") as their frontier. This left the tract between the two as a no-man's land. Since there was very little vegetation and almost no habitation in this area, there was no urgent need to control it. However, regular trade caravans passed through the area between Ladakh and Kashgar, which were open to robber raids. Securing trade was of high import to the new regime in Jammu and Kashmir.[13][17]

Robert Barkley Shaw, a British merchant resident in Kangra, India, visited Xaidulla in 1868 on his trip to Yarkand, via Leh, Ladakh and the Nubra Valley, over the Karakoram Pass. He was held in detention there for a time in a small fort made of sun-dried bricks on a shingly plain near the Karakash River which, at that time, was under the control of the Governor of Yarkand on behalf of the ruler of Kashgaria, Yaqub Beg.[18] Shaw says there was no village at all: "it is merely a camping-ground on the regular old route between Ladâk and Yârkand, and the first place where I should strike that route. Four years ago [i.e. in 1864], while the troubles were still going on in Toorkistân, the Maharaja of Cashmeer sent a few soldiers and workmen across the Karakoram ranges (his real boundary), and built a small fort at Shahidoolla. This fort his troops occupied during two summers; but last year, when matters became settled; and the whole country united under the King of Yarkand, these troops were withdrawn."[19]

Robert Shaw's nephew, Francis Younghusband, visited Xaidulla in 1889 and reported: "At Shahidula there was the remains of an old fort, but otherwise there were no permanent habitations. And the valley, though affording that rough pasturage upon which the hardy sheep and goats, camels and ponies of the Kirghiz find sustenance, was to the ordinary eye very barren in appearance, and the surrounding mountains of no special grandeur. It was a desolate, unattractive spot."[20]

He also reported that it was over 12,000 ft (3,658 m) in altitude and that nothing was grown there. All grain had to be imported from the villages of Turkestan, a six days' march over a pass 17,000 ft (5,182 m) high. It was also some 180 miles (290 km) to the nearest village in Ladakh over three passes averaging over 18,000 ft (5,486 m).[21]

20th and 21st centuries

By the early 20th century, the whole region was under Chinese control and considered part of Xinjiang Province,[22] and has remained so ever since. Xaidulla is well to the north of any territories claimed by either India or Pakistan, while the Sanju and Kilian passes are further to the north of Xaidulla. A major Chinese road runs from Yecheng in the Tarim Basin, south through Xaidulla, and across the Aksai Chin region controlled by China, but claimed by India, and into northwestern Tibet.[23]

Footnotes

- ↑ Northern Ngari in Detail: Activities, Lonely Planet, retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ Mehra, An "agreed" frontier 1992, p. 62.

- ↑ Phanjoubam, The Northeast Question 2015, pp. 12–14.

- ↑ Warikoo, Trade relations between Central Asia and Kashmir Himalayas 1996, paragraph 2.

- ↑ Rizvi, The trans-Karakoram trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries 1994, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1967), Age of the Nandas and Mauryas, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, pp. 220–221, ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1 ; Mirsky, Jeannette (1998), Sir Aurel Stein: Archaeological Explorer, University of Chicago Press, p. 83, ISBN 978-0-226-53177-9

- ↑ Les pays d’Occident d’après le Heou Han chou.” Édouard Chavannes. T’oung pao 8 (1907), p. 175, n. 1.

- ↑ Stein, Serindia (1921), Vol. I, pp. 86-87

- ↑ Hulsewé & Loewe (1979), p. 100

- ↑ Stein, Serindia (1921), Vol. I, pp. 86-87

- ↑ “Han Measures.” A.F.P. Hulsewé. T’oung Pao, Second Series, Vol. 49, Livr. 3 (1961), p. 467.

- ↑ Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar. Robert Shaw. London, John Murray. Reprint, Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, 1984.

- 1 2 Rizvi, The trans-Karakoram trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (1994), pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Datta, Chaman Lal (1984), General Zorawar Singh, His Life and Achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan, and Tibet, Deep & Deep Publications, p. 63

- ↑ Mehra, An "agreed" frontier (1992), p. 57: "Shahidulla was occupied by the Dogras almost from the time they conquered Ladakh."

- ↑ Mehra, An "agreed" frontier (1992): "In his detailed memorandum, Younghusband recalled it was always accepted that the frontier extended up to the Muztagh mountains and the Karakoram pass, the only unsettled question being as to whether it should include Shahidulla."

- ↑ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Shaw (1871), pp. 100-

- ↑ Shaw (1871), p. 107

- ↑ Younghusband (1924), p. 108

- ↑ Younghusband (1896), pp. 223-224

- ↑ Stanton (1908), Map. No. 19 - Sinkiang

- ↑ National Geographic Atlas of China (2008), p. 28.

References

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via Questia, (Subscription required (help))

- Hill, John E. (2015), Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes 1st to 2nd Centuries CE Volumes I and II., Charleston, SC.: CreateSpace, ISBN 978-1500696702 and ISBN 978-1503384620 . For a downloadable early draft of this book see the Silk Road Seattle website hosted by the University of Washington at: https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/texts.html

- Hulsewé, A.F.P.; Loewe, M. A. N. (1979), China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 B.C.-A.D. 23, Leiden: E.J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-05884-2

- Mehra, Parshotam (1992), An "agreed" frontier: Ladakh and India's northernmost borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press

- National Geographic Atlas of China (2008). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-1-4262-0136-3.

- Phanjoubam, Pradip (2015), The Northeast Question: Conflicts and frontiers, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-34003-4

- Rizvi, Janet (2016). "The trans-Karakoram trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 31 (1): 27–64. doi:10.1177/001946469403100102. ISSN 0019-4646.

- Shaw, Robert (1984) [first published by John Murray in 1871], Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-583830-0

- Stanton, Edward (1908), Atlas of the Chinese Empire. (Prepared for the China Inland Mission), London: Morgan & Scott Ltd.

- Stein, M. Aurel (1921), Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols., London, Oxford, Clarendon Press. Reprint, Motilal Banarsidass, 1980. London; Delhi . File downloadable from:

- Warikoo, K. (1996), "Trade relations between Central Asia and Kashmir Himalayas during the Dogra period (1846-1947)", Cahiers d'Asia Centrale

- Younghusband, Francis (1977) [1924], Wonders of the Himalayas, Chandigarh: Abhishek Publications

- Younghusband, Francis (2005) [first published by John Murray in 1896], The Heart of a Continent, Elbiron Classics, ISBN 1-4212-6551-6 (pbk); ISBN 1-4212-6550-8 (hardcover)