Border

Borders are geographic boundaries of political entities or legal jurisdictions, such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Borders are established through agreements between political or social entities that control those areas; the creation of these agreements is called boundary delimitation.types o

Some borders—such as a state's internal administrative border, or inter-state borders within the Schengen Area—are often open and completely unguarded. Other borders are partially or fully controlled, and may be crossed legally only at designated border checkpoints and border zones may be controlled.

Borders may even foster the setting up of buffer zones. A difference has also been established in academic scholarship between border and frontier, the latter denoting a state of mind rather than state boundaries.[1]

Borders

Types of borders :- superimposed border,relict border, physical borders,geometric border

In the past, many borders were not clearly defined lines; instead there were often intervening areas often claimed and fought over by both sides, sometimes called marchlands. Special cases in modern times were the Saudi Arabian–Iraqi neutral zone from 1922 to 1981 and the Saudi–Kuwaiti neutral zone from 1922 until 1970. In modern times, marchlands have been replaced by clearly defined and demarcated borders. For the purposes of border control, airports and seaports are also classed as borders. Most countries have some form of border control to regulate or limit the movement of people, animals, and goods into and out of the country. Under international law, each country is generally permitted to legislate the conditions that have to be met in order to cross its borders, and to prevent people from crossing its borders in violation of those laws.

Some borders require presentation of legal paperwork like passports and visas, or other identity documents, for persons to cross borders. To stay or work within a country's borders aliens (foreign persons) may need special immigration documents or permits; but possession of such documents does not guarantee that the person should be allowed to cross the border.

Moving goods across a border often requires the payment of excise tax, often collected by customs officials. Animals (and occasionally humans) moving across borders may need to go into quarantine to prevent the spread of exotic infectious diseases. Most countries prohibit carrying illegal drugs or endangered animals across their borders. Moving goods, animals, or people illegally across a border, without declaring them or seeking permission, or deliberately evading official inspection, constitutes smuggling. Controls on car liability insurance validity and other formalities may also take place.

In places where smuggling, migration, and infiltration are a problem, many countries fortify borders with fences and barriers, and institute formal border control procedures. These can extend inland, as in the United States where the U.S. Customs and Border Protection service has jurisdiction to operate up to 100 miles from any land or sea boundary.[2] On the other hand, some borders are merely signposted. This is common in countries within the European Schengen Area and on rural sections of the Canada–United States border. Borders may even be completely unmarked, typically in remote or forested regions; such borders are often described as "porous". Migration within territorial borders, and outside of them, represented an old and established pattern of movement in African countries, in seeking work and food, and to maintain ties with kin who had moved across the previously porous borders of their homelands. When the colonial frontiers were drawn, Western countries attempted to obtain a monopoly on the recruitment of labor in many African countries, which altered the practical and institutional context in which the old migration patterns had been followed, and some might argue, are still followed today. The frontiers were particularly porous for the physical movement of migrants, and people living in borderlands easily maintained transnational cultural and social networks.

A border may have been:

- Agreed by the countries on both sides

- Imposed by the country on one side

- Imposed by third parties, e.g. an international conference

- Inherited from a former state, colonial power or aristocratic territory

- Inherited from a former internal border, such as within the former Soviet Union

- Never formally defined.

In addition, a border may be a de facto military ceasefire line.

Classification

Political borders

Political borders are imposed on the world through human agency.[3] That means that although a political border may follow a river or mountain range, such a feature does not automatically define the political border, even though it may be a major physical barrier to crossing.

Political borders are often classified by whether or not they follow conspicuous physical features on the earth.

Natural borders

Natural borders are geographical features that present natural obstacles to communication and transport. Existing political borders are often a formalization of such historical, natural obstacles.

Some geographical features that often constitute natural borders are:

- Oceans: oceans create very costly natural borders. Very few countries span more than one continent. Only very large and resource-rich states are able to sustain the costs of governance across oceans for longer periods of time.

- Rivers: some political borders have been formalized along natural borders formed by rivers. Some examples are: the Niagara River (Canada–USA), the Rio Grande (Mexico–USA), the Rhine (France–Germany), and the Mekong (Thailand–Laos). If a precise line is desired, it is often drawn along the thalweg, the deepest line along the river. In the Hebrew Bible, Moses defined the middle of the river Arnon as the border between Moab and the Israelite tribes settling east of the Jordan (Deuteronomy 3:16). The United States Supreme Court ruled in 1910 that the boundary between the American states of Maryland and West Virginia is the south bank of the Potomac River.

- Lakes: larger lakes create natural borders. One example is the natural border created by Lake Tanganyika, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia on its west shore and Tanzania and Burundi on the east.

- Forests: denser jungles or forests can create strong natural borders. One example of a natural forest border is the Amazon rainforest, separating Brazil and Bolivia from Peru, Colombia, Venezuela and Guyana.

- Mountain ranges: research on borders suggests that mountains have especially strong effects as natural borders. Many nations in Europe and Asia have had their political borders defined along mountain ranges, often along a drainage divide.

Throughout history, technological advances have reduced the costs of transport and communication across the natural borders. That has reduced the significance of natural borders over time. As a result, political borders that have been formalized more recently, such as those in Africa or Americas, typically conform less to natural borders than very old borders, such as those in Europe or Asia, do.

Geometric borders

Geometric boundaries are formed by straight lines (such as lines of latitude or longitude), or occasionally arcs (Pennsylvania/Delaware), regardless of the physical and cultural features of the area. Such political boundaries are often found around the states that developed out of colonial holdings, such as in North America, Africa and the Middle East.

Fiat borders

A generalization of the idea of geometric borders is the idea of fiat boundaries by which is meant any sort of boundary that does not track an underlying bona fide physical discontinuity (fiat, latin for “let it be done”, a decision). Fiat boundaries are typically the product of human demarcation, such as in demarcating electoral districts or postal districts.[4]

Relict borders

A relict border is a former boundary, which may no longer be a legal boundary at all. However, the former presence of the boundary can still be seen in the landscape. For instance, the boundary between East and West Germany is no longer an international boundary, but it can still be seen because of historical markers on the landscape, and it is still a cultural and economic division in Germany.

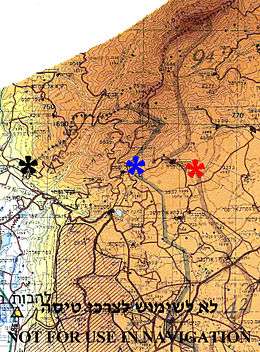

Lines of Control

A line of control (LoC) refers to a militarized buffer border between two or more nations that is yet to be resolved or implemented for permanent border status. LoC borders are under military control and are not recognized as an official international border. Formally known as a cease-fire line an LoC was first created as a way to buffer war borders during the Simla Agreement[5]. Similar to a cease-fire line an LoC is the result of war, stalemates and land ownership conflict[6].

Maritime borders

A maritime border is a division enclosing an area in the ocean where a nation has exclusive rights over the mineral and biological resources,[7] encompassing maritime features, limits and zones.[8] Maritime borders represent the jurisdictional borders of a maritime nation[9] and are recognized by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Maritime borders exist in the context of territorial waters, contiguous zones, and exclusive economic zones; however, the terminology does not encompass lake or river boundaries, which are considered within the context of land boundaries.

Some maritime borders have remained indeterminate despite efforts to clarify them. This is explained by an array of factors, some of which illustrate regional problems.[10]

Airspace borders

Airspace is the atmosphere located within a countries controlled international and maritime borders. All sovereign countries hold the right to regulate and protect air space under the international law of Air sovereignty[11]. The horizontal boundaries of airspace are similar to the policies of "high seas" in maritime law. Airspace extends 12 nautical miles from the coast of a country and it holds responsibility for protecting its own airspace unless under NATO peacetime protection[12][13]. With international agreement a country can assume the responsibility of protecting or controlling the atmosphere over International Airspaces such as the Pacific Ocean. The vertical boundaries of airspace are not officially set or regulated internationally. However there is a general agreement of vertical airspace ending at the point of the Kármán line[14]. The Kármán line is a peak point at the altitude of 62 mi (100 km) above the earths surface, setting a boundary between the earths atmosphere and outer space[15]. Airspace regulations are set by nations and local governments within an airspace, regulations of airspace differ by country and location.

Types of International Borders

Open Borders

An open border is the deregulation and or lack of regulation on the movement of persons between nations and jurisdictions, this does not apply to trade or movement between privately owned land areas[16]. Most nations have open borders for travel within their nation of travel, examples of this include the United States and Canada. However only a handful of nations have deregulated open borders with other nations, an example of this being all European Union members under the Schengen Agreement[17]. Open borders used to be very common amongst all nations. However post WW1 lead to the regulation of open borders, making them less common and no longer feasible for most industrialized nations[18].

Regulated Borders

Regulated Borders have varying degrees of control on the movement of persons and trade between nations and jurisdictions. Most Industrialized nations have regulations on entry and require one or more of the following procedures: visa check, passport check or customs checks[19]. Most regulated borders have regulations on immigration, types of wildlife and plants, and illegal objects such as drugs or weapons. Overall border regulations are placed by national and local governments and can very depending on nation and current political, or economic conditions. Some of the most regulated borders in the world include: Australia, the United States, Israel, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates[20]. These nations have government controlled border agencies and organizations that enforce border regulation policies on and within their borders.

Demilitarized zones

A Demilitarized zone (DMZ) is a border separating two or more nations, groups or militaries that have agreed to prohibit the use of military activity or force within the borders bounds. A DMZ can act as a war boundary, cease fire line, wildlife preserve, or in some cases as a de facto international border. An example of a demilitarized international border is the 38th parallel between North and South Korea[21]. Other notable DMZ zones include Antarctica and outer space (consisting of all space 100 miles away from the earth's surface), both are preserved for world research and exploration[22][23]. Due to the prohibition of control by nations a DMZ can become unexposed to human influence and in turn developed into a natural border or wildlife preserve, this is present on the Korean Demilitarized Zone, the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone, and the Green Line in Cyprus[24][25].

Border economics

The presence of borders often fosters certain economic features or anomalies. Wherever two jurisdictions come into contact, special economic opportunities arise for border trade. Smuggling provides a classic case; contrariwise, a border region may flourish on the provision of excise or of import–export services — legal or quasi-legal, corrupt or legitimate. Different regulations on either side of a border may encourage services to position themselves at or near that border: thus the provision of pornography, of prostitution, of alcohol, fireworks, and/or of narcotics may cluster around borders, city limits, county lines, ports and airports. In a more planned and official context, Special Economic Zones (SEZs) often tend to cluster near borders or ports.

Even if the goods are not perceived to be undesirable, states will still seek to document and regulate the cross-border trade in order to collect tariffs and benefit from foreign currency exchange revenues.[26] Thus, there is the concept unofficial trade in goods otherwise legal; for example, the cross-border trade in livestock by pastoralists in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia sells an estimated $250 to $300 million of livestock to Somalia, Kenya and Djibouti every year unofficially, over 100 times the official estimate.[26]

Human economic traffic across borders (apart from kidnapping) may involve mass commuting between workplaces and residential settlements. The removal of internal barriers to commerce, as in France after the French Revolution or in Europe since the 1940s, de-emphasises border-based economic activity and fosters free trade. Euroregions are similar official structures built around commuting across boundary.

Politics

Political borders have a variety of meanings for those whom they affect. Many borders in the world have checkpoints where border control agents inspect persons and/or goods crossing the boundary.

In much of Europe, controls on persons were abolished by the 1985 Schengen Agreement and subsequent European Union legislation. Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, the competence to pass laws on crossing internal and external borders within the European Union and the associated Schengen Area states (Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein) lies exclusively within the jurisdiction of the European Union, except where states have used a specific right to opt out (United Kingdom and Ireland, which maintain the Common Travel Area amongst themselves).

The United States has notably increased measures taken in border control on the Canada–United States border and the United States–Mexico border during its War on Terrorism (See Shantz 2010). One American writer has said that the 3,600 km (2,200 mi) US-Mexico border is probably "the world's longest boundary between a First World and Third World country".[27]

Historic borders such as the Great Wall of China, the Maginot Line, and Hadrian's Wall have played a great many roles and been marked in different ways. While the stone walls, the Great Wall of China and the Roman Hadrian's Wall in Britain had military functions, the entirety of the Roman borders were very porous, which encouraged Roman economic activity with neighbors.[28] On the other hand, a border like the Maginot Line was entirely military and was meant to prevent any access in what was to be World War II to France by its neighbor, Germany; Germany ended up going around the Maginot Line through Belgium just as it had done in World War I.

Cross-border regions

Macro-regional integration initiatives, such as the European Union and NAFTA, have spurred the establishment of cross-border regions. These are initiatives driven by local or regional authorities, aimed at dealing with local border-transcending problems such as transport and environmental degradation.[29] Many cross-border regions are also active in encouraging intercultural communication and dialogue as well as cross-border economic development strategies.

In Europe, the European Union provides financial support to cross-border regions via its Interreg programme. The Council of Europe has issued the Outline Convention on Transfrontier Co-operation, providing a legal framework for cross-border co-operation even though it is in practice rarely used by Euroregions.

Border studies

There has been a renaissance in the study of borders during the past two decades, partially from the creation of a counter-narrative to notions of a borderless world that have been advanced as part of globalization theory.[30] Examples of recent initiatives are the Border Regions in Transition network of scholars,[31] the International Boundaries Research Unit at the University of Durham,[32] the Association of Borderlands Studies based in North America,[33] the African Borderlands Research Network (ABORNE) and the founding of smaller border research centres at Nijmegen[34] and Queen's University Belfast.[35]

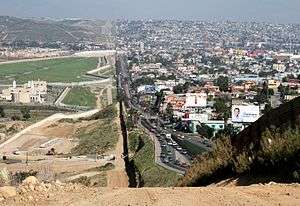

Tijuana-San Ysidro Border

.jpg)

Mexico and the United States share the world's most transited border.[36] The San Ysidro Port of Entry is located in between San Ysidro, California and Tijuana, Baja California. Approximately 50,000 vehicles and 25,000 pedestrians utilize this entry to the United States daily.[37] Due to business of this entry port, it has influenced the every day life-style of people that live in these border towns. [38]

Health Impact

There is a raising problem with the impact that the world's busiest border is causing in both sides of the border. The vehicle average wait time to cross into the United States is approximately an hour just to travel a few miles.[40] Having thousands of vehicles transit through the border every day is causing an air-pollution concern in San Ysidro and Tijuana.[41] The emission of carbon monoxide (CO) and other vehicle related air contaminants have been linked to health complications such as cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, birth outcomes, premature death and mortality, obesity, asthma and other respiratory diseases.[42]Due to the high levels of traffic collusion and the extended wait times, mental health is also impacted by the border's business, affecting the person's stress levels and aggressive behavior.[43]

Socio-Economic Impact

The San Ysidro border is heavily militarized, separated by three walls, border patrol agents and the ICE police.[44] However, this does not stop these two cultures from exchanging art, music, traditions, and language. In San Ysidro, 87.9% of the households speak Spanish, you can pay visits to the local mall and notice that many employees will be bilingual.[45] While for Tijuana, it is not to the same extent, however, a lot of the slang is rooted from English words creating Spanglish, which a mix of both languages. On both sides of the border, the social dynamic among these two major cities is influenced by one another.[46]

Tijuana is the next target for San Diegan developers due to the fast-growing city, their lower cost of living, cheap prices and it's proximity to San Diego.[47] While this would benefit the tourist aspect of the city, it is damaging to low-income residents that will no longer be able to afford the cost of living in Tijuana.[48] Tijuana is the home to many deportees from the United States, many who have lost everything and do not have an income to rely on and are now in a new city in which they have to quickly adapt in order to survive.[49] San Diego developers would bring many benefits to Tijuana but deportees and the poor run the risk of being impacted by the gentrification of Tijuana.[50]

Images gallery

The following pictures show in how many different ways international and regional borders can be closed off, monitored, at least marked as such, or simply unremarkable.

- Borders of the World

Border at Tijuana, Mexico and San Ysidro, California, United States. A straight-line border surveyed when the region was thinly populated.

Border at Tijuana, Mexico and San Ysidro, California, United States. A straight-line border surveyed when the region was thinly populated.- A sign showing the limits of the Frontier Closed Area, a 28-km² area along the Hong Kong-side of the 30-km-long border between Hong Kong and mainland China.

The bridge over the Anarjohka in Karigasniemi, on the border of Finland with Norway

The bridge over the Anarjohka in Karigasniemi, on the border of Finland with Norway

The Peace Arch at the Canada–United States border, the longest common border in the world.

The Peace Arch at the Canada–United States border, the longest common border in the world. A sign at the Polish-Czech border near Králický Sněžník, indicating that only citizens of the European Union and of five more states may cross. When the Schengen rules became applicable in 2007, the sign became obsolete.

A sign at the Polish-Czech border near Králický Sněžník, indicating that only citizens of the European Union and of five more states may cross. When the Schengen rules became applicable in 2007, the sign became obsolete.

- A border within a closely built-up area – near Aachen between Germany and the Netherlands: Germany starts at the red line drawn in the photo.

Border between the Netherlands and Belgium next to a street café in Baarle Nassau and Baarle Hertog. Some European borders originate from former land ownership boundaries.

Border between the Netherlands and Belgium next to a street café in Baarle Nassau and Baarle Hertog. Some European borders originate from former land ownership boundaries.- The metal strip within the building of the Eurode Business Centre marks the border between the Netherlands and Germany, in Kerkrade and Herzogenrath.

The border between the Netherlands (right) and Germany (left) is located in the center of this residential road, and, nowadays, completely unmarked.

The border between the Netherlands (right) and Germany (left) is located in the center of this residential road, and, nowadays, completely unmarked.- Italy/Switzerland border stone at Passo San Giacomo. Some borders were broadly defined by treaty, and surveyors would then choose a suitable line on the ground.

- Guadiana International Bridge at the Portugal-Spain border, whose limits were established by the Treaty of Alcañices in 1297. It is one of the oldest borders in the world.

The marker between the United States and Canada in Waterton-Glacier National Park.

The marker between the United States and Canada in Waterton-Glacier National Park. A road crossing the Republic of Ireland-United Kingdom border from the British side. This border is entirely open: the only indication that one is crossing into the Republic of Ireland is a speed limit sign in kilometers per hour (signs in the United Kingdom are in miles per hour).

A road crossing the Republic of Ireland-United Kingdom border from the British side. This border is entirely open: the only indication that one is crossing into the Republic of Ireland is a speed limit sign in kilometers per hour (signs in the United Kingdom are in miles per hour). A train crossing the China–Russia border, travelling from Zabaykalsk in Russia to Manzhouli in China.

A train crossing the China–Russia border, travelling from Zabaykalsk in Russia to Manzhouli in China. The winding border between Pakistan and India is lit by security lights. It is one of the few places on Earth where an international boundary can be seen at night.

The winding border between Pakistan and India is lit by security lights. It is one of the few places on Earth where an international boundary can be seen at night.

See also

- Border control

- Boundary (real estate)

- Geopolitics

- List of countries and territories by land and maritime borders

- List of countries that border only one other country

- List of international border rivers

- List of countries and territories by land borders

- List of bordering countries with greatest relative differences in GDP (PPP) per capita

- List of land borders with dates of establishment

- List of national border changes since World War I

- Political geography

- Political science

References

- ↑ Mura, Andrea (2016). "National Finitude and the Paranoid Style of the One". Contemporary Political Theory. 15: 58–79. doi:10.1057/cpt.2015.23.

- ↑ The Constitution in the 100-Mile Border Zone

- ↑ Robinson, Edward Heath. Reexamining Fiat, Bona Fide and Force Dynamic Boundaries for Geopolitical Entities and their Placement in DOLCE Applied Ontology 2012 7: pp. 93–108

- ↑ Smith, Barry, 1995, "On Drawing Lines on a Map" in A. U. Frank, W. Kuhn and D. M. Mark (eds.), Spatial Information Theory. Proceedings of COSIT 1995, Berlin/Heidelberg/Vienna/New York/London/Tokyo: Springer Verlag, 475–484.

- ↑ "Simla Agreement". Stimson Center. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- ↑ VLIZ Maritime Boundaries Geodatabase, General info; retrieved 19 November 2010

- ↑ Geoscience Australia, Maritime definitions; retrieved 19 November 2010

- ↑ United States Department of State, Maritime boundaries; retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ↑ Valencia, Mark J. (2001). Maritime Regime Building: Lessons Learned and Their Relevance for Northeast Asia, pp. 149–166., p. 149, at Google Books

- ↑ "Air law". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "Air law". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "Allied Air Command | NATO Air Policing". ac.nato.int. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ Reinhardt, Dean (July 2018). "The Vertical Limit of State Sovereignty" (PDF). The Vertical Limit of State Sovereignty. 1: 3.

- ↑ "Bulletin 20 - Space Weapons Ban: Thoughts on a New Treaty". 2008-05-15. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "open border Definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary". 2016-05-03. Archived from the original on 2016-05-03. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ Anonymous (2016-12-06). "Schengen Area - Migration and Home Affairs - European Commission". Migration and Home Affairs - European Commission. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "International Union for the Scientific Study of Population : XXIV General Population Conference, Salvador da Bahia, Brazil : Plenary Debate no 4"(PDF). Web.archive.org. 24 August 2001. Archived from the original on August 1, 2014. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "Types of International Borders a". www.siue.edu. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ Groundwater, Ben (2016-11-30). "Border Force: The world's toughest customs and immigration". Traveller. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ↑ "demilitarized zone (DMZ) | Definition, Facts, & Pictures". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "Antarctic Treaty | 1959". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "Outer Space Treaty | 1967". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ "Wildlife preserve planned for Korean demilitarized zone". Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ Ahearn, Ashley. "Military Zones Mean Boon For Biodiversity". Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- 1 2 Pavanello, Sara 2010. Working across borders – Harnessing the potential of cross-border activities to improve livelihood security in the Horn of Africa drylands Archived 2010-11-12 at the Wayback Machine.. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ Murphy, Cullen. Roman Empire: gold standard of immigration. Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1907 (accessed here June 20, 2007)

- ↑ Murphy 2007

- ↑ Perkmann, M, Building governance institutions across European borders, Regional Studies, 1999, Vol: 33, pages: 657–667, hdl.handle.net

- ↑ D. Newman & A. Paasi, `Fences and neighbours in the post-modern world: boundary narratives in political geography', Progress in Human Geography, 22 (2), 186–207, 1998; D. Newman, "The lines that continue to separate us: Borders in our borderless world", Progress in Human Geography, Vol 30 (2), 1–19, 2006.

- ↑ Border Regions in Transition IX Conference, North American and European Border Regions in Comparative Perspective: Markets, States and Border Communities, (January 12–15, 2008) Victoria, BC Canada and Bellingham, WA United States.

- ↑ International Boundaries Research Unit, University of Durham.

- ↑ Association for Borderland Studies.

- ↑ Nijmegen Centre for Border Research.

- ↑ Centre for International Borders Research (CIBR) Queen's University Belfast

- ↑ Bogan, Jesse. "In Pictures: America's Busiest Border Crossings". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "A Day at the Busiest Border Crossing in the World". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ Ahmed, Azam. "Before the Wall: Life Along the U.S.-Mexico Border". Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ MESA, OTAY. "Border Wait Times and Border Crossing Statistics - OTAYMESA". OTAYMESA. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ MESA, OTAY. "Border Wait Times and Border Crossing Statistics - OTAYMESA". OTAYMESA. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "San Ysidro Is Getting a Clearer Look at Just How Polluted it Is - Voice of San Diego". Voice of San Diego. 2018-04-23. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "Border Health Equity Transportation Study" (PDF). February 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Border Health Equity Transportation Study" (PDF). February 27, 2015.

- ↑ "The World's Most Dangerous Borders". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "Languages in San Ysidro, San Diego, California (Neighborhood) - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ Monografias.com, Roberto Rosique ,. "Las influencias culturales y artísticas entre México del Norte y Norteamérica - Monografias.com". www.monografias.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "Cost of Living in Tijuana, Mexico. Jul 2018 prices in Tijuana". Expatistan, cost of living comparisons. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "Tijuana Wants You To Forget Everything You Know About It". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ Lakhani, Nina (2017-12-12). "This is what the hours after being deported look like". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ↑ "San Diego Developers See a New Frontier in Tijuana". Voice of San Diego. 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

Further reading

- Border Stories – A website devoted to stories from both sides of the U.S. Mexico Border

- Talking Borders online audio archive at Queen's University Belfast

- The World in 2015: National borders undermined? 11-min video interview with Bernard Guetta, a columnist for Libération newspaper and France Inter radio. "For [Guetta], one of the main lessons from international relations in 2014 is that national borders are becoming increasingly irrelevant. These borders, drawn by the colonial powers, were and still are entirely artificial. Now, people want borders along national, religious or ethnic lines. Bernard Guetta calls this a "comeback of real history"."

- James, Paul (2014). "Faces of Globalization and the Borders of States: From Asylum Seekers to Citizens". Citizenship Studies. vol. 18 (no. 2): 208–23.

- Mura, Andrea (2016). "National Finitude and the Paranoid Style of the One". Contemporary Political Theory. 15: 58–79. doi:10.1057/cpt.2015.23.

- Said Saddiki, World of Walls: The Structure, Roles and Effectiveness of Separation Barriers. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0121

External links

![]()

| Look up border in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Collection of pictures of European borders, mainly intra-Schengen borders

- Institut Européen des Itinéraires Culturels homepage

- Border Ireland – database of activities and publications on cross-border co-operation on the island of Ireland since 1980's

- Gallery of 1100 borderpoints in the world

- Baltic Borderlands Greifswald