Nanjing

Nanjing (![]()

Nanjing 南京市 Nanking, Nan-ching | |

|---|---|

Prefecture-level & Sub-provincial city | |

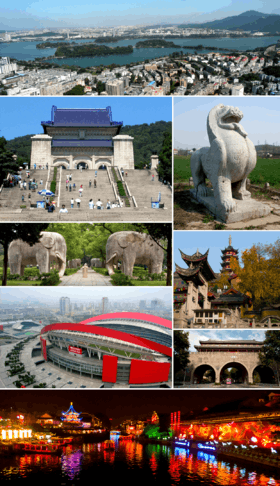

Clockwise from top: 1. the city, Xuanwu Lake and Purple Mountain; 2. stone sculpture "bixie"; 3. Jiming Temple; 4. Yijiang Gate with the City Wall of Nanjing; 5. Qinhuai River and Fuzi Miao; 6. Nanjing Olympic Sports Center; 7. the spirit way of Ming Xiaoling; 8. Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum | |

| |

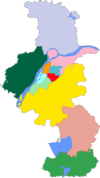

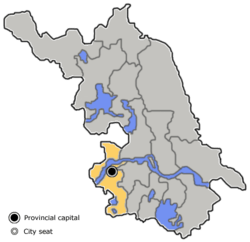

Location of Nanjing City jurisdiction in Jiangsu | |

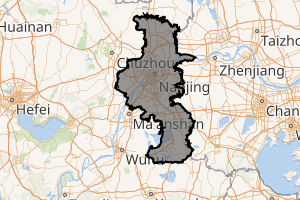

Nanjing Location in China  Nanjing Nanjing (China) | |

| Coordinates (Jiangsu People's Government): 32°03′41″N 118°45′49″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China[lower-alpha 1] |

| Province | Jiangsu |

| County-level | 11 |

| Township-level | 129 |

| Settled | unknown (Yecheng, 495 BCE. Jinling City, 333 BCE) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • Party Secretary | Zhang Jinghua |

| • Mayor | Han Liming |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level & Sub-provincial city | 6,587 km2 (2,543 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,398.69 km2 (540.04 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 20 m (50 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Prefecture-level & Sub-provincial city | 8,505,500 |

| • Density | 1,237/km2 (3,183/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018)[3] | 6,525,000 |

| • Metro | 11.7 million |

| Demonym(s) | Nankinese[lower-alpha 2] |

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 210000–211300 |

| Area code(s) | 25 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-JS-01 |

| GDP (Nominal) | 2018 |

| - Total | US$191.1 billion |

| - Per capita | US$23,104 |

| - Growth | |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 |

| - Total | US$ 334.1 billion |

| - Per capita | US$40,084 |

| Human Development Index | 0.859 (very high) |

| Website | City of Nanjing |

Deodar Cedar (Cedrus deodara), Platanus × acerifolia[5] Méi (Prunus mume) | |

| Nanjing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Nanjing" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 南京 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Nanking | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Southern Capital" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Situated in the Yangtze River Delta region, Nanjing has a prominent place in Chinese history and culture, having served as the capital of various Chinese dynasties, kingdoms and republican governments dating from the 3rd century to 1949,[8] and has thus long been a major center of culture, education, research, politics, economy, transport networks and tourism, being the home to one of the world's largest inland ports. The city is also one of the fifteen sub-provincial cities in the People's Republic of China's administrative structure,[9] enjoying jurisdictional and economic autonomy only slightly less than that of a province.[10] Nanjing has been ranked seventh in the evaluation of "Cities with Strongest Comprehensive Strength" issued by the National Statistics Bureau, and second in the evaluation of cities with most sustainable development potential in the Yangtze River Delta. It has also been awarded the title of 2008 Habitat Scroll of Honor of China, Special UN Habitat Scroll of Honor Award and National Civilized City.[11]

Nanjing has many high-quality universities and research institutes, with the number of universities listed in 100 National Key Universities ranking third, including Nanjing University which has a long history and is among the world top 10 universities ranked by Nature Index.[12] The ratio of college students to total population ranks No.1 among large cities nationwide. Nanjing is one of the top three Chinese scientific research centers, according to the Nature Index,[13] especially strong in the chemical sciences.

Nanjing, one of the nation's most important cities for over a thousand years, is recognized as one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China. It has been one of the world's largest cities, enjoying peace and prosperity despite wars and disasters.[14][15][16][17] Nanjing served as the capital of Eastern Wu (229–280), one of the three major states in the Three Kingdoms period; the Eastern Jin and each of the Southern dynasties (Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang and Chen), which successively ruled southern China from 317–589; the Southern Tang (937–75), one of the Ten Kingdoms; the Ming dynasty when, for the first time, all of China was ruled from the city (1368–1421);[18] and the Republic of China under the right-wing Kuomintang (1927–37, 1946–49) prior to its flight to Taiwan by Chiang Kai-Shek during the Chinese Civil War.[19] The city also served as the seat of the rebel Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (1853–64) and the Japanese puppet regime of Wang Jingwei (1940–45) during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It suffered severe atrocities in both conflicts, such as the Nanjing massacre.

Nanjing has served as the capital city of Jiangsu province since the establishment of the People's Republic of China. It has many important heritage sites, including the Presidential Palace and Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum. Nanjing is famous for human historical landscapes, mountains and waters such as Fuzimiao, Ming Palace, Chaotian Palace, Porcelain Tower, Drum Tower, Stone City, City Wall, Qinhuai River, Xuanwu Lake and Purple Mountain. Key cultural facilities include Nanjing Library, Nanjing Museum and Nanjing Art Museum.

Names

The city has a number of other names, and some historical names are now used as names of districts of the city; among them there is the name Jiangning or Kiangning (江寧), whose former character Jiang (江, Yangtze) is the former part of the name Jiangsu and latter character Ning (寧, simplified form 宁; 'Peace') is the short name of Nanjing. When it was the capital of China, for instance under the ROC, Jing (京; 'Capital') was adopted as the abbreviation of Nanjing.

The city first became a Chinese national capital as early as the Jin dynasty. The name Nanjing, which means "Southern Capital", was officially designated for the city during the Ming dynasty, about six hundred years later.[lower-alpha 4] Nanjing is sometimes known as Jinling or Ginling (金陵, "Gold Hill") of the eponymous Ginling College; the old name has been used since the Warring States period in the Zhou dynasty.[20]

History

Early history and foundation

Archaeological discovery shows that "Nanjing Man" lived more than 500 thousand years ago. Zun, a kind of wine vessel, was found to exist in Beiyinyangying culture of Nanjing in about 5000 years ago.[21] In the late period of Shang dynasty, Taibo of Zhou came to Jiangnan and established Wu state, and the first stop is in Nanjing area according to some historians based on discoveries in Taowu and Hushu culture.[22] According to a legend quoted by an artist in Ming dynasty, Chen Yi, Fuchai, King of the State of Wu, founded a fort named Yecheng in today's Nanjing area in 495 BC.[23] Later in 473 BC, the State of Yue conquered Wu and constructed the fort of Yuecheng (越城) on the outskirts of the present-day Zhonghua Gate. In 333 BC, after eliminating the State of Yue, the State of Chu built Jinling Yi (金陵邑)[24] in the western part of present-day Nanjing.[25] It was renamed Moling (秣陵) during the reign of the First Emperor of Qin. Since then, the city experienced destruction and renewal many times. The area was successively part of Kuaiji, Zhang and Danyang prefectures in Qin and Han dynasty, and part of Yangzhou region which was established as the nation's 13 supervisory and administrative regions in the 5th year of Yuanfeng in Han dynasty (106 BC). Nanjing was later the capital city of Danyang Prefecture, and had been the capital city of Yangzhou for about 400 years from late Han to early Tang.

Capital of the Six Dynasties

Nanjing first became a state capital in AD 229, when the state of Eastern Wu founded by Sun Quan during the Three Kingdoms period relocated its capital to Jianye (建業), the city extended on the basis of Jinling Yi in AD 211.[18] Although conquered by the Western Jin dynasty in 280, Nanjing and its neighboring areas had been well cultivated, developing into one of the commercial, cultural and political centers of China during the Eastern Wu.[17] This city would soon play a vital role in the following centuries.

Shortly after the unification of the region, the Western Jin dynasty collapsed. First the rebellions by eight Jin princes for the throne and later rebellions and invasion from Xiongnu and other nomadic peoples that destroyed the rule of the Jin dynasty in the north. In 317, remnants of the Jin court, as well as nobles and wealthy families, fled from the north to the south and reestablished the Jin court in Nanjing, which was then called Jiankang (建康), replacing Luoyang.[27] This marked the first time a Chinese dynastic capital moved to southern China.

During the period of North–South division, Nanjing remained the capital of the Southern dynasties for more than two and a half centuries. During this time, Nanjing was the international hub of East Asia.[28] Based on historical documents, the city had 280,000 registered households.[29] Assuming an average Nanjing household consisted of about 5.1 people, the city had more than 1.4 million residents.[27]

A number of sculptural ensembles of that era, erected at the tombs of royals and other dignitaries, have survived (in various degrees of preservation) in Nanjing's northeastern and eastern suburbs, primarily in Qixia and Jiangning District.[30] Possibly the best preserved of them is the ensemble of the Tomb of Xiao Xiu (475–518), a brother of Emperor Wu of Liang.[31][32]

Six Dynasties is a collective term for six Chinese dynasties mentioned above which all maintained national capitals at Jiankang. The six dynasties were: Eastern Wu (222–280), Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420) and four southern dynasties (420–589).

Destruction and revival

The birds are gone, the Terrace empty, and the river flows on.

Flourishing flowers of Wu Palace are buried beneath dark trails;

Caps and gowns of Jin times all lie in ancient mounds.

The Three-peaked Mountain lies half visible under the blue sky,

The two-forked stream is separated by the White-Egret Isle in the middle.

Clouds always block the sun,

Chang'an cannot be seen and I grieve.

— About the former opulent capital Jinling (present-day Nanjing) in the poem Climbing Phoenix Terrace at Jinling by Li Bai of the Tang dynasty[33]

The period of division ended when the Sui dynasty reunified China and almost destroyed the entire city, turning it into a small town. The city was razed after the Sui took it over. It was renamed Shengzhou (昇州) in the Tang dynasty and resuscitated during the late Tang.[34]

It was chosen as the capital and called Jinling (金陵) during the Southern Tang (937–976), which succeeded the state of Yang Wu.[35] It was renamed Jiangning (江寧) in the Northern Song and renamed Jiankang in the Southern Song. Jiankang's textile industry burgeoned and thrived during the Song despite the constant threat of foreign invasions from the north by the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty. The court of Da Chu, a short-lived puppet state established by the Jurchens, and the court of Song were once in the city.[36][37][38]

The Southern Song were eventually exterminated by the Mongols; during their rule as the Yuan dynasty, the city's status as a hub of the textile industry was further consolidated.[39] According to Odoric of Pordenone, Chilenfu (Nanjing) had 360 stone bridges, which were finer than anywhere else in the world. It was well populated and had a large craft industry.[40]

Southern capital of Ming dynasty

The first emperor of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang (the Hongwu Emperor), who overthrew the Yuan dynasty, renamed the city Yingtian (應天), rebuilt it, and made it the dynastic capital in 1368. He constructed a 48 km (30 mi) long city wall around Yingtian, as well as a new Ming Palace complex, and government halls.[41] It took 200,000 laborers 21 years to finish the wall, which was intended to defend the city and its surrounding region from coastal pirates.[42] The present-day City Wall of Nanjing was mainly built during that time and today it remains in good condition and has been well preserved.[43] It is among the longest surviving city walls in China.[44] The Jianwen Emperor ruled from 1398 to 1402.

It is believed that Nanjing was the largest city in the world from 1358 to 1425 with a population of 487,000 in 1400.[45] In 1421, the Yongle Emperor relocated the capital to Beijing. The city began to be called the 'southern capital' – Nanjing (南京), in comparison to the capital in the north. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor, wished to revert the relocation of the imperial capital from Nanjing to Beijing that had happened during the Yongle reign.[46] On 24 February 1425, he appointed Admiral Zheng He as the defender of Nanjing and ordered him to continue his command over the Ming treasure fleet for the city's defense.[46]

Zheng He governed the city with three eunuchs for internal matters and two military noblemen for external matters, awaiting the Hongxi Emperor's return along with the military establishment from the north.[46] The emperor died on 29 May 1425 before this could have taken place,[46][47] so Beijing remained the de facto capital and Nanjing remained the secondary capital.[47] The succeeding Xuande Emperor remained in Beijing, so the aforementioned Nanjing government eventually became a permanent institution.[48] In official Ming documents of 1425 to 1441, Nanjing was designated as the capital and Beijing was designated as the temporary capital.[49] In 1441, Emperor Yingzong ordered to not to prefix the word "provisional" (行在) on the Beijing Government seals any longer, while Nanjing's need to prefix "Nanjing" for distinguishing purposes remained. Hence, Nanjing still had itself imperial government with extremely limited power before 1644.

Besides the city wall, other Ming-era structures in the city included the famous Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum and Porcelain Tower, although the latter was destroyed by the Taipings in the 19th century either to prevent a hostile faction from using it to observe and shell the city[50] or from superstitious fear of its geomantic properties.[51]

A monument to the huge human cost of some of the gigantic construction projects of the early Ming dynasty is the Yangshan Quarry (located some 15–20 km (9–12 mi) east of the walled city and Ming Xiaoling mausoleum), where a gigantic stele, cut on the orders of the Yongle Emperor, lies abandoned, just as it was left 600 years ago when it was understood it was impossible to move or complete it.[52]

As the center of the empire, early-Ming Nanjing had worldwide connections. It was home of the admiral Zheng He, who went to sail the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and it was visited by foreign dignitaries, such as a king from Borneo (渤泥; Bóní), who died during his visit to China in 1408. The Tomb of the King of Boni, with a spirit way and a tortoise stele, was discovered in Yuhuatai District (south of the walled city) in 1958, and has been restored.[53]

Over two centuries after the removal of the capital to Beijing, Nanjing was destined to become the capital of a Ming emperor one more time. After the fall of Beijing to Li Zicheng's rebel forces and then to the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in the spring of 1644, the Ming prince Zhu Yousong was enthroned in Nanjing in June 1644 as the Hongguang Emperor.[54][55] His short reign was described by later historians as the first reign of the so-called Southern Ming dynasty.[56]

_-_panoramio.jpg)

Zhu Yousong, however, fared a lot worse than his ancestor Zhu Yuanzhang three centuries earlier. Beset by factional conflicts, his regime could not offer effective resistance to Qing forces, when the Qing army, led by the Manchu prince Dodo approached Jiangnan the next spring.[57] Days after Yangzhou fell to the Manchus in late May 1645, the Hongguang Emperor fled Nanjing, and the imperial Ming Palace was looted by local residents.[58] On June 6, Dodo's troops approached Nanjing, and the commander of the city's garrison, Zhao the Earl of Xincheng, promptly surrendered the city to them.[59][60] The Manchus soon ordered all male residents of the city to shave their heads in the Manchu queue way.[61] They requisitioned a large section of the city for the bannermen's cantonment, and occupied the former imperial Ming Palace, but otherwise the city was spared the mass murders and destruction that befell Yangzhou.[62]

Despite capturing many counties in his initial attack due to surprise and having the initiative, Koxinga announced the final battle in Nanjing in 1659 ahead of time giving plenty of time for the Qing to prepare because he wanted a decisive, single grand showdown like his father succsfully did against the Dutch at the Battle of Liaoluo Bay, throwing away the surprise and initiative which led to its failure. Koxinga's attack on Qing held Nanjing which would interrupt the supply route of the Grand Canal leading to possible starvation in Beijing caused such fear that the Manchus (Tartares) considered returning to Manchuria (Tartary) and abandoning China according to a 1671 account by a French missionary.[63] The commoners and officials in Beijing and Nanjing were waiting to support whichever side won. An official from Qing Beijing sent letters to family and another official in Nanjing, telling them all communication and news from Nanjing to Beijing had been cut off, that the Qing were considering abandoning Beijing and moving their capital far away to a remote location for safety since Koxinga's iron troops were rumored to be invincible. The letter said it reflected the grim situation being felt in Qing Beijing. The official told his children in Nanjing to prepare to defect to Koxinga which he himself was preparing to do. Koxinga's forces intercepted these letters and after reading them Koxinga may have started to regret his deliberate delays allowing the Qing to prepare for a final massive battle instead of swiftly attacking Nanjing.[64] Koxinga's Ming loyalists fought against a majority Han Chinese Bannermen Qing army when attacking Nanjing. The siege lasted almost three weeks, beginning on August 24. Koxinga's forces were unable to maintain a complete encirclement, which enabled the city to obtain supplies and even reinforcements—though cavalry attacks by the city's forces were successful even before reinforcements arrived. Koxinga's forces were defeated and "slipped back" (Wakeman's phrase) to the ships which had brought them.[65]

Qing dynasty and Taiping Rebellion

Under the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the Nanjing area was known as Jiangning and served as the seat of government for the Viceroy of Liangjiang.[66] It was the site of a Qing Army garrison.[67] It had been visited by the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors a number of times on their tours of the southern provinces. Nanjing was threatened to be invaded by British troops during the close of the First Opium War, which was ended by the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. As the capital of the brief-lived rebel Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in the mid-19th century, Nanjing was known as Tianjing (天京; '"Heavenly Capital" or "Capital of Heaven"'). The rebellion destroyed most of the former Ming imperial buildings in the city, including the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing.

Both the Qing viceroy and the Taiping king resided in buildings that would later be known as the Presidential Palace. When Qing forces led by Zeng Guofan retook the city in 1864, a massive slaughter occurred in the city with over 100,000 estimated to have committed suicide or fought to the death.[68] Since the Taiping Rebellion began, Qing forces allowed no rebels speaking its dialect to surrender.[69] This systematic mass murder of civilians occurred in Nanjing.[70]

The New York Methodist Mission Society's Superintendent, Virgil Hart arrived in Nanking in 1881. After some time, he eventually thwarted its officials by buying a piece of property near the South Gate and Confucius Temple; to build the city's first Methodist Church, western hospital (Blackstone Methodist Hospital) and Boys' School. The hospital would later be unified with the Drum Tower Hospital and the Boys' School would be expanded by later Missionaries to become the University of Nanking and Medical School. The old Mission property would become the No. 13 Middle School, the city's oldest/continuous school grounds in the city.[71]

Capital of the republic and Nanking Massacre

The Xinhai Revolution led to the founding of the Republic of China in January 1912 with Sun Yat-sen as the first provisional president and Nanjing was selected as its new capital. However, the Qing Empire controlled large regions to the north, so revolutionaries asked Yuan Shikai to replace Sun as president in exchange for the abdication of Puyi, the last emperor. Yuan demanded the capital be Beijing (closer to his power base).

In 1927, the Kuomintang (KMT; Nationalist Party) under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek again established Nanjing as the capital of the Republic of China, and this became internationally recognized once KMT forces took Beijing in 1928. The following decade is known as the Nanking decade. During this decade, Nanjing was of symbolic and strategic importance. The Ming dynasty had made Nanjing a capital, the republic had been established there in 1912, and Sun Yat-sen's provisional government had been there. Sun's body was brought and placed in a grand mausoleum to cement Chiang's legitimacy. Chiang was born in the neighboring province of Zhejiang and the general area had strong popular support for him.

In 1927, the Nationalist government proposed a comprehensive planning proposal, the Capital Plan (首都計劃), to reconstruct the war-torn city of Nanjing into a modern capital. It was a decade of extraordinary growth with an enormous amount of construction. A lot of government buildings, residential houses, and modern public infrastructures were built. During this boom, Nanjing reputedly became one of the most modern cities in China.

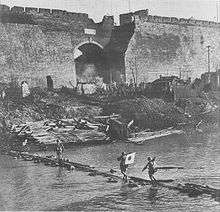

In 1937, the Empire of Japan started a full-scale invasion of China after invading Manchuria in 1931, beginning the Second Sino-Japanese War (often considered a theater of World War II).[72] Their troops occupied Nanjing in December and carried out the systematic and brutal Nanking massacre (the "Rape of Nanking").[73] Even children, the elderly, and nuns are reported to have suffered at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Army.[74] The total death toll, including estimates made by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal after the atomic bombings, was between 300,000 and 350,000.[75] The city itself was also severely damaged during the massacre.[73] The Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall was built in 1985 to commemorate this event.

A few days before the fall of the city, the National Government of China was relocated to the southwestern city Chungking (Chongqing) and resumed Chinese resistance. In 1940, a Japanese-collaborationist government known as the "Nanjing Regime" or "Reorganized National Government of China" led by Wang Jingwei was established in Nanjing as a rival to Chiang Kai-shek's government in Chongqing.[76] In 1946, after the Surrender of Japan, the KMT relocated its central government back to Nanjing.

Chinese Civil War and People's Republic

On 21 April 1949, Communist forces crossed the Yangtze River. On April 23, the Communist People's Liberation Army (PLA) captured Nanjing.[77] The KMT government retreated to Canton (Guangzhou) until October 15, Chongqing until November 25, and then Chengdu before retreating to the island of Taiwan on December 10 where Taipei was proclaimed the temporary capital of the Republic of China. By late 1949, the PLA was pursuing remnants of KMT forces southwards in southern China, and only Tibet and Hainan Island were left. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in October 1949, Nanjing was initially a province-level municipality, but it was soon merged into Jiangsu and again became the provincial capital by replacing Zhenjiang which was transferred in 1928, and retains that status to this day.

Geography

Nanjing, with a total land area of 6,598 km2 (2,548 sq mi), is situated in the heartland of the drainage area of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, and in the Yangtze River Delta, one of the largest economic zones of China. The Yangtze River flows past the west side and then the north side of Nanjing City, while the Ningzheng Ridge surrounds the north, east and south sides of the city. The city is 650 km (400 mi) southeast of Luoyang, 900 km (560 mi) south-southeast of Beijing, 270 km (170 mi) west-northwest of Shanghai, and 1,200 km (750 mi) east-northeast of Chongqing. The Yangtze River flows downstream from Jiujiang, Jiangxi, through Anhui and Jiangsu to the East China Sea. The northern part of the lower Yangtze drainage basin is the Huai River basin and the southern part is the Zhe River basin; they are connected by the Grand Canal east of Nanjing. The area around Nanjing is called Xiajiang (下江, Downstream River) region, with Jianghuai dominant in the northern part and Jiangzhe dominant in the southern part.[lower-alpha 5] The region is also well known as Dongnan (东南, South East, the Southeast) and Jiangnan (江南, and River South, South of Yangtze).[lower-alpha 6]

Nanjing borders Yangzhou to the northeast (one town downstream when following the north bank of the Yangtze); Zhenjiang to the east (one town downstream when following the south bank of the Yangtze); and Changzhou to the southeast. On its western boundary is Anhui, where Nanjing borders five prefecture-level cities: Chuzhou to the northwest, Wuhu, Chaohu and Ma'anshan to the west and Xuancheng to the southwest.[78]

Nanjing is at the intersection of the Yangtze River, an east–west water transport artery, and the Nanjing–Beijing railway, a north–south land transport artery, hence the name “door of the east and west, throat of the south and north”. Furthermore, the west part of the Ningzhen range is in Nanjing; the Loong-like Zhong Mountain curls round the east side of the city, while the tiger-like Stone Mountain crouches in the west of the city, hence the name “the Zhong Mountain, a dragon curling, and the Stone Mountain, a tiger crouching”.

Climate and environment

| Nanjing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nanjing has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) and is influenced by the East Asian monsoon. The four seasons are distinct, with damp conditions seen throughout the year, very hot and muggy summers, cold, damp winters, and in between, spring and autumn are of reasonable length. Along with Chongqing and Wuhan, Nanjing is traditionally referred to as one of the "Three Furnaces" along the Yangtze River for the perennially high temperatures in the summertime.[80] However, the time from mid-June to the end of July is the plum blossom blooming season in which the meiyu (rainy season of East Asia; literally "plum rain") occurs, during which the city experiences a period of mild rain as well as dampness. Typhoons are uncommon but possible in the late stages of summer and early part of autumn. The annual mean temperature is around 15.91 °C (60.6 °F), with the monthly 24-hour average temperature ranging from 2.7 °C (36.9 °F) in January to 28.1 °C (82.6 °F) in July. Extremes since 1951 have ranged from −14.0 °C (7 °F) on 6 January 1955 to 40.7 °C (105 °F) on 22 August 1959.[81][82][83] On average precipitation falls 115 days out of the year, and the average annual rainfall is 1,090 mm (43 in). With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 37 percent in March to 52 percent in August, the city receives 1,926 hours of bright sunshine annually.

Nanjing is endowed with rich natural resources, which include more than 40 kinds of minerals. Among them, iron and sulfur reserves make up 40 percent of those of Jiangsu province. Its reserves of strontium rank first in East Asia and the South East Asia region. Nanjing also possesses abundant water resources, both from the Yangtze River and groundwater. In addition, it has several natural hot springs such as Tangshan Hot Spring in Jiangning and Tangquan Hot Spring in Pukou.

Sun Yat-sen once summarized and lauded the feature of Nanjing in his book The International Development of China (建國方略):

Nanking was the old capital of China before Peking, and is situated in a fine locality which comprises high mountains, deep water and a vast level plain—a rare site to be found in any part of the world. It also lies at the center of a very rich country on both sides of the lower Yangtze. (南京為中國古都,在北京之前,而其位置乃在一美善之地區。其地有高山,有深水,有平原,此三種天工,鐘毓一處,在世界中之大都市誠難覓如此佳境也。而又恰居長江下游兩岸最豐富區域之中心...)[84]

To be more exact, surrounded by the Yangtze River and mountains, the urban area of the city enjoys its scenic natural environment. Xuanwu Lake and Mochou Lake are located in the center of the city and are easily accessible to the public, while Purple Mountain is covered with deciduous and coniferous forests preserving various historical and cultural sites. Meanwhile, a Yangtze River deep-water channel is under construction to enable Nanjing to handle the navigation of 50,000 DWT vessels from the East China Sea.[85]

| Climate data for Nanjing (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

27.7 (81.9) |

30.3 (86.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

38.1 (100.6) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.7 (105.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.0 (6.8) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

16.9 (62.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−13.1 (8.4) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45.2 (1.78) |

52.1 (2.05) |

80.4 (3.17) |

79.9 (3.15) |

90.7 (3.57) |

162.0 (6.38) |

216.3 (8.52) |

143.5 (5.65) |

75.3 (2.96) |

59.5 (2.34) |

56.3 (2.22) |

29.5 (1.16) |

1,090.7 (42.95) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 8.7 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 6.2 | 113.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 71 | 76 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 75 | 76 | 73 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 124.7 | 120.3 | 144.7 | 169.2 | 194.2 | 162.8 | 196.7 | 201.6 | 164.0 | 164.2 | 147.4 | 137.1 | 1,926.9 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration (precipitation days, sunshine data 1971–2000)[79][86] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Environmental issues

Air pollution in 2013

A dense wave of smog began in the central and east parts of China on 2 December 2013 across a distance of around 1,200 km (750 mi),[87] including Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Anhui, Shanghai and Zhejiang. A lack of cold air flow, combined with slow-moving air masses carrying industrial emissions, collected airborne pollutants to form a thick layer of smog over the region.[88] The heavy smog heavily polluted central and southern Jiangsu Province, especially in and around Nanjing,[89] with its AQI pollution Index at "severely polluted" for five straight days and "heavily polluted" for nine.[90] On 3 December 2013, levels of PM2.5 particulate matter average over 943 micrograms per cubic meter,[91] falling to over 338 micrograms per cubic meter on 4 December 2013.[92] Between 3:00 pm, 3 December and 2:00 pm, 4 December local time, several expressways from Nanjing to other Jiangsu cities were closed, stranding dozens of passenger buses in Zhongyangmen bus station.[89] From 5 to 6 December, Nanjing issued a red alert for air pollution and closed down all kindergarten through middle schools. Children's Hospital outpatient services increased by 33 percent; general incidence of bronchitis, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections significantly increased.[93] The smog dissipated 12 December.[94] Officials blamed the dense pollution on lack of wind, automobile exhaust emissions under low air pressure, and coal-powered district heating system in north China.[95] Prevailing winds blew low-hanging air masses of factory emissions (mostly SO2) towards China's east coast.[96]

Government

At present, the full name of the government of Nanjing is "People's Government of Nanjing City" and the city is under the one-party rule of the CPC, with the CPC Nanjing Committee Secretary as the de facto governor of the city and the mayor as the executive head of the government working under the secretary.

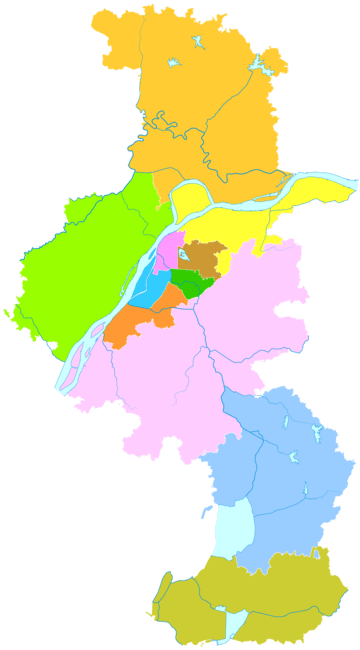

Administrative divisions

The sub-provincial city of Nanjing is divided into 11 districts.[97]

| Map | Subdivision | Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2010) | Area (km2) | Density (/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1

2

3

4

Pukou

Qixia

Yuhuatai

Jiangning

Luhe

Lishui

Gaochun

1. Xuanwu

2. Qinhuai

3. Jianye

4. Gulou

| ||||||

| City Proper | ||||||

| Xuanwu District | 玄武区 | Xuánwǔ Qū | 651,957 | 75.46 | 8,639.77 | |

| Qinhuai District | 秦淮区 | Qínhuái Qū | 1,007,992 | 49.11 | 20,525.19 | |

| Jianye District | 建邺区 | Jiànyè Qū | 426,999 | 82.93 | 5,148.91 | |

| Gulou District | 鼓楼区 | Gǔlóu Qū | 1,271,191 | 53.00 | 23,998.47 | |

| Qixia District | 栖霞区 | Qīxiá Qū | 664,503 | 381.01 | 1,744.06 | |

| Yuhuatai District | 雨花台区 | Yǔhuātái Qū | 391,285 | 132.39 | 2,955.55 | |

| Suburban | ||||||

| Pukou District | 浦口区 | Pǔkǒu Qū | 710,298 | 910.49 | 780.13 | |

| Jiangning District | 江宁区 | Jiāngníng Qū | 1,145,628 | 1,577.75 | 726.12 | |

| Luhe District | 六合区 | Lùhé Qū[98][99] | 915,845 | 1,470.99 | 622.60 | |

| Lishui District | 溧水区 | Lìshuǐ Qū | 421,323 | 1063.67 | 396.10 | |

| Gaochun District | 高淳区 | Gāochún Qū | 417,129 | 790.23 | 527.86 | |

| Total | 8,004,680 | 6587.02 | 1,215.22 | |||

| Defunct districts: Baixia District and Xiaguan District | ||||||

Demographics

|

|

At the time of the 2010 census, the total population of the City of Nanjing was 8.005 million. The OECD estimated the encompassing metropolitan area at the time as 11.7 million.[4] Official statistics in 2011 estimated the city's population to be 8.11 million. The birth rate was 8.86 percent and the death rate was 6.88 percent. The urban area had a population of 6.47 million people. The sex ratio of the city population was 107.31 males to 100 females.[101][102]

As in most of eastern China, the official ethnic makeup of Nanjing is predominantly Han nationality (98.56 percent), with 50 other official ethnic groups. In 1999, 77,394 residents belonged to officially defined minorities, among which the vast majority (64,832) were Hui, contributing 83.76 percent to the minority population. The second and third largest minority groups were Manchu (2,311) and Zhuang (533). Most of the minority nationalities resided in Jianye District, comprising 9.13 percent of the district's population.[103]

Economy

Earlier development

There was a massive cultivating in the area of Nanjing from the Three Kingdoms period to Southern dynasties. The sparse population led to land as royal rewards were granted for rules’ people. At first, the landless peasants benefited from it, then the senior officials and aristocratic families. Since large numbers of immigrants flooded into the area, reclamation was quite common in its remote parts, which promoted its agricultural development.

The craft industries, by contrast, had a faster growth. Especially the textiles section, there were about 200,000 craftsmen by the late Qing.[104] Several dynasties established their imperial textiles bureaus in Nanjing. The Nanjing Brocade (南京云锦) is their exquisite product as the cloth for the royal garments such as dragon robes. Meanwhile, the satins from Nanjing were called "tribute satins" ("贡缎"), because they were usually paid as tribute to the monarchy. Besides, minting, papermaking, shipbuilding grew initially since the Three Kingdoms period. As Nanjing was the capital of the Ming dynasty, the industries further expanded, where both state-owned and numerous private businesses served the imperial court. Several place names in Nanjing remains witnessed them, such as Wangjinshi (网巾市, the market sells wangjin), Guyilang (估衣廊, the corridor for garments bargain), Youfangqiao (油坊桥, the bridge near an oil mill).

Moreover, the trade in Nanjing was also flourishing. The Ming dynasty drawing Prosperous Nanjing (南都繁会图卷; Nándū Fánhuì Tújuǎn) depicts a vivid market scene bustling with people and full of various sorts of shops. However, the economic developments were almost wiped out by the Taiping Rebellion's catastrophe.

Modern times

Into the first half of the twentieth century after the establishment of ROC, Nanjing gradually shifted from being a production hub towards being a heavy consumption city, mainly because of the rapid expansion of its wealthy population after Nanjing once again regained the political spotlight of China. A number of huge department stores such as Zhongyang Shangchang sprouted up, attracting merchants from all over China to sell their products in Nanjing. In 1933, the revenue generated by the food and entertainment industry in the city exceeded the sum of the output of the manufacturing and agriculture industry. One third of the city population worked in the service industry, .

In the 1950s after PRC was established by CPC, the government invested heavily in the city to build a series of state-owned heavy industries, as part of the national plan of rapid industrialization, converting it into a heavy industry production center of east China.[105] Overenthusiastic in building a “world-class” industrial city, the government also made many disastrous mistakes during development, such as spending hundreds of millions of yuan to mine for non-existent coal, resulting in negative economic growth in the late 1960s. From the 1960s to 1980s there were five pillar industries, namely, electronics, automobiles, petrochemical, iron and steel, and power, each with big state-owned firms. After the Reform and Opening recovering market economy, the state-owned enterprises found themselves incapable of competing with efficient multinational firms and local private firms, hence were either mired in heavy debt or forced into bankruptcy or privatization and this resulted in large numbers of laid-off workers who were technically not unemployed but effectively jobless.

Today

The current economy of the city is basically newly developed based on the past. Service industries are dominating, accounting for about 60 percent of the GDP of the city, and financial industry, culture industry and tourism industry are top 3 of them. Industries of information technology, energy saving and environmental protection, new energy, smart power grid and intelligent equipment manufacturing have become pillar industries.[106] Big civilian-run enterprise include Suning Commerce, Yurun, Sanpower, Fuzhong, Hiteker, 5stars, Jinpu, Tiandi, CTTQ Pharmaceutical, Nanjing Iron and Steel Company and Simcere Pharmaceutical. Big state-owned firms include Panda Electronics, Yangzi Petrochemical, Jinling Petrochemical, Nanjing Chemical, Jincheng Motors, Jinling Pharmaceutical, Chenguang and NARI. The city has also attracted foreign investment, multinational firms such as Siemens, Ericsson, Volkswagen, Iveco, A.O. Smith, and Sharp have established their lines, and a number of multinationals such as Ford, IBM, Lucent, Samsung and SAP established research center there. Many China-based leading firms such as Huawei, ZTE and Lenovo have key R&D institutes in the city. Nanjing is an industrial technology research and development hub, hosting many R&D centers and institutions, especially in areas of electronics technology, information technology, computer software, biotechnology and pharmaceutical technology and new material technology.

In recent years, Nanjing has been developing its economy, commerce, industry, as well as city construction. In 2013 the city's GDP was RMB 801 billion (3rd in Jiangsu), and GDP per capita (current price) was RMB 98,174(US$16041), an 11 percent increase from 2012. The average urban resident's disposable income was RMB 36,200, while the average rural resident's net income was RMB 14,513. The registered urban unemployment rate was 3.02 percent, lower than the national average (4.3 percent). Nanjing's Gross Domestic Product ranked 12th in 2013 in China, and its overall competence ranked 6th in mainland and 8th including Taiwan and Hong Kong in 2009.[107]

- Industrial zones

There are a number of industrial zones in Nanjing.

Transport

Nanjing is the transport hub in eastern China and the downstream Yangtze River area. Different means of transport constitute a three-dimensional transport system that includes land, water and air. As in most other Chinese cities, public transport is the dominant mode of travel for the majority of citizens. As from October 2014, Nanjing had four bridges and two tunnels over the Yangtze River, linking districts north of the river with the city center on the south bank.[108]

Rail

Nanjing is an important railway hub in eastern China.[109] It serves as rail junction for the Beijing-Shanghai (Jinghu) (which is itself composed of the old Jinpu and Huning Railways), Nanjing–Tongling Railway (Ningtong), Nanjing–Qidong (Ningqi), and the Nanjing-Xi'an (Ningxi) which encompasses the Hefei–Nanjing Railway. Nanjing is connected to the national high-speed railway network by Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway and Shanghai–Wuhan–Chengdu Passenger Dedicated Line, with several more high-speed rail lines under construction.

Among all 17 railway stations in Nanjing, passenger rail service is mainly provided by Nanjing Railway Station and Nanjing South Railway Station, while other stations like Nanjing West Railway Station, Zhonghuamen Railway Station and Xianlin Railway Station serve minor roles. Nanjing Railway Station was first built in 1968.[110] On November 12, 1999, the station was burnt in a serious fire.[111] Reconstruction of the station was finished on September 1, 2005. Nanjing South Railway Station, which is one of the 5 hub stations on Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway, has officially been claimed as the largest railway station in Asia and the second largest in the world in terms of GFA (Gross Floor Area).[112] Construction of Nanjing South Station began on 10 January 2008.[113] The station was opened for public service in 2011.[114]

Road

As an important regional hub in the Yangtze River Delta, Nanjing is well-connected by over 60 state and provincial highways to all parts of China.

Motorways such as Hu–Ning, Ning–He, Ning–Hang enable commuters to travel to Shanghai, Hefei, Hangzhou, and other important cities quickly and conveniently. Inside the city of Nanjing, there are 230 km (140 mi) of highways, with a highway coverage density of 3.38 kilometers per hundred square kilometers (5.44 mi/100 sq mi). The total road coverage density of the city is 112.56 kilometers per hundred square kilometers (181.15 mi/100 sq mi).[115] The two artery roads in Nanjing are Zhongshan Road and Hanzhong. The two roads cross in the city center, Xinjiekou.

Expressways {G+XXxx (National Express, 国家高速), S+XX (省级高速)}:

- G25 Changchun–Shenzhen Expressway(长深高速或宁杭高速)

- G36 Nanjing–Luoyang Expressway(宁洛高速)

- G40 Shanghai–Xi'an Expressway(沪陕高速)

- G42 Shanghai–Chengdu Expressway(沪蓉高速或沪宁高速)

- G4211 Nanjing–Wuhu Expressway, a spur of G42 that extends west to Wuhu, Anhui(宁芜高速)

- S55 Nanjing–Gaochun(Xuancheng) Expressway(宁宣高速或南京机场高速)

- S38 Yanjiang Expressway(沿江高速或常合高速)

- G2501 Nanjing Ring Expressway(新南京绕城高速或南京绕越高速)

- S001 Nanjing Ring Highway(旧南京绕城高速或南京绕城公路)

National Highway {G1xx (which starts from Beijing), G2xx (north-south), G3xx (west-east)}:

- China National Highway 104—motorists can either drive northwest to Beijing or south to Fuzhou, Fujian.

- China National Highway 205—motorists can either drive north to Shanhaiguan, Hebei or south to Shenzhen, Guangdong.

- China National Highway 312—motorists can either drive east to Shanghai or west to Khorgas, Xinjiang on the Kazakh border

- China National Highway 328—Nanjing is the western terminus of G328, which motorists can follow to Hai'an County in eastern Jiangsu

Public transport

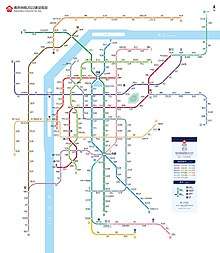

The city also boasts an efficient public transport network, which mainly consists of bus, taxi and metro systems. The bus network, which is currently run by three companies since 2011, provides more than 370 routes covering all parts of the city and suburban areas.[116] At present, the Nanjing Metro system has a grand total of 377 km (234 mi) of route and 173 stations across 10 lines. They are Line 1, Line 2, Line 3, Line 4, Line 10, Line S1, Line S3, Line S7, Line S8 and Line S9. The city is planning to complete a 17-line Metro and light-rail system by 2030.[117] The expansion of the Metro network will greatly facilitate intracity transport and reduce the currently heavy traffic congestion.

Air

Nanjing's airport, Lukou International Airport, serves both national and international flights. In 2013, Nanjing airport handled 15,011,792 passengers and 255,788.6 tonnes of freight.[118] The airport currently has 85 routes to national and international destinations, which include Japan,[119] Korea, Thailand,[120][121] Malaysia, Singapore, United States[122] and Germany. The airport is connected by a 29-kilometer (18 mi) highway directly to the city center, and is also linked to various intercity highways, making it accessible to the passengers from the surrounding cities. A railway Ninggao Intercity Line has been built to link the airport with Nanjing South Railway Station.[123] Lukou Airport was opened on 28 June 1997, replacing Nanjing Dajiaochang Airport as the main airport serving Nanjing. Dajiaochang Airport is still used as a military air base.[124] Nanjing has another airport – Nanjing Ma'an International Airport which temporarily serves as a dual-use military and civil airport.

Water

The Port of Nanjing is the largest inland port in China, with annual cargo tonnage reached 191,970,000 t in 2012.[125] The port area is 98 km (61 mi) in length and has 64 berths including 16 berths for ships with a tonnage of more than 10,000.[126] Nanjing is also the biggest container port along the Yangtze River; in March 2004, the one million container-capacity base, Longtan Containers Port Area opened, further consolidating Nanjing as the leading port in the region. As of 2010, it operated six public ports and three industrial ports.[127] The Yangtze River's 12.5-meter-deep waterway enables 50,000-ton-class ocean ships directly arrive at the Nanjing Port, and the ocean ships with the capacities of 100,000 tons or above can also reach the port after load reduction in the Yangtze River's high-tide period.[128] CSC Jinling has a large shipyard.[129]

Yangtze River crossings

In the 1960s, the first Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge was completed, and served as the only bridge crossing over the Lower Yangtze in eastern China at that time. The bridge was a source of pride and an important symbol of modern China, having been built and designed by the Chinese themselves following failed surveys by other nations and the reliance on and then rejection of Soviet expertise. Begun in 1960 and opened to traffic in 1968, the bridge is a two-tiered road and rail design spanning 4,600 meters on the upper deck, with approximately 1,580 meters spanning the river itself. Since then four more bridges and two tunnels have been built. Going in the downstream direction, the Yangtze crossings in Nanjing are: Dashengguan Bridge, Line 10 Metro Tunnel, Third Bridge, Nanjing Yangtze River Tunnel(南京长江隧道), First Bridge, Second Bridge and Fourth Bridge,Nanjing Yangtze Tunnel (南京扬子江隧道). In the near future, Such Yangtze Crossings will be added as follow :Jianning West Rd. Tunnel, Xianxin Rd. Tunnel, Heyan Rd. Tunnel, Fifth Nanjing Yangtze Bridge.

Culture and art

Being one of the four ancient capitals of China, Nanjing has always been a cultural center attracting intellectuals from all over the country. In the Tang and Song dynasties, Nanjing was a place where poets gathered and composed poems reminiscent of its luxurious past; during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the city was the official imperial examination center (Jiangnan Examination Hall) for the Jiangnan region, again acting as a hub where different thoughts and opinions converged and thrived.

Today, with a long cultural tradition and strong support from local educational institutions, Nanjing is commonly viewed as a "city of culture" and one of the more pleasant cities to live in China.

Art

Some of the leading art groups of China are based in Nanjing; they include the Qianxian Dance Company, Nanjing Dance Company, Jiangsu Peking Opera Institute and Nanjing Xiaohonghua Art Company among others.

Jiangsu Province Kun Opera is one of the best theaters for Kunqu, China's oldest stage art.[130] It is considered a conservative and traditional troupe. Nanjing also has professional opera troupes for the Yang, Yue (shaoxing), Xi and Jing (Chinese opera varieties) as well as Suzhou pingtan, spoken theater and puppet theater.

Jiangsu Art Gallery is the largest gallery in Jiangsu Province, presenting some of the best traditional and contemporary art pieces of China like the historical Master Ho-Kan;[131] many other smaller-scale galleries, such as Red Chamber Art Garden and Jinling Stone Gallery, also have their own special exhibitions.

Festivals

Many traditional festivals and customs were observed in the old times, which included climbing the City Wall on January 16, bathing in Qing Xi on March 3, hill hiking on September 9 and others (the dates are in Chinese lunar calendar). Almost none of them, however, are still celebrated by modern Nanjingese.

Instead, Nanjing, as a tourist destination, hosts a series of government-organized events throughout the year. The annual International Plum Blossom Festival held in Plum Blossom Hill, the largest plum collection in China, attracts thousands of tourists both domestically and internationally. Other events include Nanjing Baima Peach Blossom and Kite Festival, Jiangxin Zhou Fruit Festival and Linggu Temple Sweet Osmanthus Festival.

Libraries

Nanjing Library, founded in 1907, houses more than 10 million volumes of printed materials and is the third largest library in China, after the National Library in Beijing and Shanghai Library. Other libraries, such as city-owned Jinling Library and various district libraries, also provide considerable amount of information to citizens. Nanjing University Library is the second largest university libraries in China after Peking University Library, and the fifth largest nationwide, especially in the number of precious collections.

Museums

Nanjing has some of the oldest and finest museums in China. Nanjing Museum, formerly known as National Central Museum during ROC period, is the first modern museum and remains as one of the leading museums in China having 400,000 items in its permanent collection.[132] The museum is notable for enormous collections of Ming and Qing imperial porcelain, which is among the largest in the world.[133] Other museums include the City Museum of Nanjing in the Chaotian Palace, the Oriental Metropolitan Museum,[lower-alpha 7] the China Modern History Museum in the Presidential Palace, the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, the Taiping Kingdom History Museum, Jiangning Imperial Silk Manufacturing Museum,[lower-alpha 8] Nanjing Yunjin Museum, Nanjing City Wall Cultural Museum, Nanjing Customs Museum in Ganxi House,[lower-alpha 9] Nanjing Astronomical History Museum, Nanjing Paleontological Museum, Nanjing Geological Museum, Nanjing Riverstones Museum, and other museums and memorials such Zheng He Memorial[lower-alpha 10] Jinling Four Modern Calligraphers Memorial.[lower-alpha 11]

Theater

Most of Nanjing's major theaters are multi-purpose, used as convention halls, cinemas, musical halls and theaters on different occasions. The major theaters include the People's Convention Hall and the Nanjing Arts and Culture Center. The Capital Theater well known in the past is now a museum in theater/film.

Night life

Traditionally Nanjing's nightlife was mostly centered around Nanjing Fuzimiao (Confucius Temple) area along the Qinhuai River, where night markets, restaurants and pubs thrived.[135] Boating at night in the river was a main attraction of the city. Thus, one can see the statues of the famous teachers and educators of the past not too far from those of the courtesans who educated the young men in the other arts.

In the past 20 years, several commercial streets have been developed, hence the nightlife has become more diverse: there are shopping malls opening late in the Xinjiekou CBD, as well as in and around major residential areas throughout the city. The well-established "Nanjing 1912" district hosts a wide variety of recreational facilities ranging from traditional restaurants and western pubs to dance clubs, in both its downtown location and beside Baijia Lake in Jiangning District. In recent years, many night-life options have opened up in Catherine Park as well as in shopping malls such as IST in Xinjiekou and Kingmo near Baijai Lake metro station. Other, more student-oriented places are to be found near to Nanjing University and Nanjing Normal University.

Food and symbolism

The local cuisine in Nanjing is called Jinling cuisine (金陵菜) or Jingsu cuisine (京苏菜); it is part of Jiangsu province's cuisine. Jinling cuisine is famous for its meticulous process, emphasizing no added preservatives and its seasonality. Its duck and goose dishes are well known among Chinese for centuries. It also employs many different style of cooking methods, such as slow cooking, Chinese oven cooking, etc. Its dishes tend to be light and fresh, suitable for all. The restaurant specializing in Jinling cuisine is Ma Xiang Xing (马祥兴菜馆).

Many of the city's local favorite dishes are based on ducks, including Nanjing salted duck, duck blood and vermicelli soup, and duck oil pancake.[136]

The radish is also a typical food representing people of Nanjing, which has been spread through word of mouth as an interesting fact for many years in China. According to Nanjing.GOV.cn, "There is a long history of growing radish in Nanjing especially the southern suburb. In the spring, the radish tastes very juicy and sweet. It is well-known that people in Nanjing like eating radish. And the people are even addressed as 'Nanjing big radish', which means they are unsophisticated, passionate and conservative. From health perspective, eating radish can help to offset the stodgy food that people take during the Spring Festival".[137]

Sports and stadiums

Nanjing's planned 20,000 seat Youth Olympic Sports Park Gymnasium will be one of the venues for the 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup.[138]

As a major Chinese city, Nanjing is home to many professional sports teams. Jiangsu Suning FC, the football club currently staying in Chinese Super League, is a long-term tenant of Nanjing Olympic Sports Center.[139] Jiangsu Nangang Basketball Club is a competitive team which has long been one of the major clubs fighting for the title in China top level league, CBA. Jiangsu Volleyball men and women teams are also traditionally considered as at top level in China volleyball league.

There are two major sports centers in Nanjing, Wutaishan Sports Center and Nanjing Olympic Sports Center. Both of these two are comprehensive sports centers, including stadium, gymnasium, natatorium, tennis court, etc. Wutaishan Sports Center was established in 1952 and it was one of the oldest and most advanced stadiums in early time of People's Republic of China.

Nanjing hosted the 10th National Games of PRC in 2005 and hosted the 2nd summer Youth Olympic Games in 2014.[140][141]

In 2005, to host The 10th National Game of People's Republic of China, there was a new stadium, Nanjing Olympic Sports Center, constructed in Nanjing. Compared to Wutaishan Sports Center, which the major stadium's capacity is 18,500,[142] Nanjing Olympic Sports Center has a more advanced stadium which is big enough to seat 60,000 spectators. Its gymnasium has capacity of 13,000, and natatorium of capacity 3,000.

On 10 February 2010, the 122nd IOC session at Vancouver announced Nanjing as the host city for the 2nd Summer Youth Olympic Games. The slogan of the 2014 Youth Olympic Games was "Share the Games, Share our Dreams". The Nanjing 2014 Youth Olympic Games featured all 28 sports on the Olympic program and were held from 16 to 28 August. The Nanjing Youth Olympic Games Organizing Committee (NYOGOC) worked together with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to attract the best young athletes from around the world to compete at the highest level. Off the competition fields, an integrated culture and education program focused on discussions about education, Olympic values, social challenges, and cultural diversity. The YOG aims to spread the Olympic spirit and encourage sports participation.

Architecture

The city is renowned for its wide variety of architectures which mainly contain buildings from multiple dynasties, the Republic of China, and the present.

Imperial period

Inside the walled city

- City Wall of Nanjing (南京城墙)

- Gate of China (Zhonghuamen) (中华门)

- Fuzimiao (Confucius Temple) and Qinhuai River (南京夫子庙 秦淮河)

- Jiangnan Examination Hall (江南贡院)

- Zhanyuan Garden (瞻园)

- Old Gate East (Laomendong) (老门东)

- Taoye Ferry (桃叶渡)

- Ming Palace Site (明故宫)

- Xu Garden (煦园)

- Jiming Temple (鸡鸣寺)

- Beiji Ge (北极阁)

- Drum Tower of Nanjing (南京鼓楼)

- Chaotian Palace (朝天宫)

- Stone City (石头城)

- Yuejiang Tower (阅江楼)

- Jinghai Temple (静海寺)

City Wall of Nanjing and Yijiangmen Gate

City Wall of Nanjing and Yijiangmen Gate East Gate of China

East Gate of China Qinhuai River

Qinhuai River Jiming Temple

Jiming Temple- Jinghai Temple and Yuejiang Tower

Outside the walled city

- Purple Mountain Scenic Area (紫金山)

- Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum and its surrounding complex (明孝陵)

- Linggu Temple (灵谷寺)

- Xuanwu Lake (玄武湖)

- Qixia Temple (栖霞寺)

- The Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing (restored) (大报恩寺琉璃塔)

- Mochou Lake and Park (莫愁湖)

- Yangshan Quarry (阳山碑材)

- Southern Tang Mausoleums (南唐二陵)

Xuanwu Lake

Xuanwu Lake The Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing

The Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing Classical buildings in the Mochou Lake

Classical buildings in the Mochou Lake Spirit Way of Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum

Spirit Way of Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum- Tower of Linggu Temple

Qixia Temple

Qixia Temple

Republic of China period

Because it was designated as the national capital, many structures were built around that time. Here is a short list:

Inside the walled city

- Former Presidential Palace of Republic of China (中华民国总统府旧址)

- Former National Assembly Building of Republic of China (国民大会堂旧址)

- Former Central Government of ROC Building Group along N. Zhongshan Road (中山北路国民政府建筑群)

- Former Central Committee of KMT Buildings (中国国民党中央党部旧址)

- Former Foreign Embassies in Gulou Area (鼓楼使馆区旧址)

- Nanking Officials Residence Cluster along Yihe Road (颐和路公馆区)

- Former National Central Museum (国立中央博物院旧址)

- Former National Art Gallery Building (国立美术陈列馆旧址)

- Former Central Radio of KMT Building (中央广播电台旧址)

- Dahua Theater (大华电影院)

- Former Academia Sinica Buildings (国立中央研究院旧址)

- Former National Central University Buildings at Sipailou (国立中央大学旧址)

- Former University of Nanking Buildings (金陵大学旧址)

- Former Ginling College Buildings (金陵女子文理学院旧址)

- Former Republic of China Military Academy Buildings (中央陆军军官学校旧址)

- Former Bank of China Nanking Branch Building (中国银行南京分行旧址)

- Former Bank of Communications Nanking Branch Building (交通银行南京分行旧址)

- Former Central Bank of ROC Nanking Branch Building (中央银行南京分行旧址)

- Former Macklin Hospital Buildings (Gulou Hospital) (马林医院旧址)

- Former Central Hospital Buildings (国立中央医院旧址)

- St. Paul's Church (圣保罗堂)

- Central Hotel (中央饭店)

- Former Capital Hotel (Huajiang Hotel) (首都饭店/华江饭店)

- Yangtse Hotel (扬子饭店)

- Lizhishe Buildings (励志社)

.jpg) Former Presidential Palace

Former Presidential Palace- Former National Assembly Building

Yihe Road

Yihe Road Former Ministry of Foreign Affairs Buildings

Former Ministry of Foreign Affairs Buildings- Former Capital Hotel

- Former Academia Sinica Buildings

Outside the walled city

- Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum and its surrounding area (中山陵)

- National Revolutionary Army Memorial Cemetery (国民革命军阵亡将士公墓)

- Aviation Martyrs of WWII Memorial Cemetery (航空烈士公墓)

- National Purple Mountain Observatory (国立紫金山天文台)

- Former Central Stadium (中央体育场旧址)

- Nanjing Botanical Garden, Memorial Sun Yat-Sen (中山植物园)

Hall of Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum

Hall of Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum Gate of Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum

Gate of Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum.jpg) National Revolutionary Army Memorial Cemetery

National Revolutionary Army Memorial Cemetery Gate of Presidential Residence at Purple Mountain

Gate of Presidential Residence at Purple Mountain National Purple Mountain Observatory

National Purple Mountain Observatory- Central Stadium

People's Republic of China period

- Yuhuatai Memorial Park of Revolutionary Martyrs (雨花台)

- Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge (南京长江大桥)

- Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders (南京大屠杀遇难同胞纪念馆)

- Jinling Hotel (金陵饭店)

- Zifeng Tower (紫峰大厦)

Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge

Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge.jpg) Yuhuatai Memorial Park of Revolutionary Martyrs

Yuhuatai Memorial Park of Revolutionary Martyrs Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders

Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders Jinling Hotel

Jinling Hotel Zifeng Tower ranks among the tallest buildings in the world, opened for commercial operations in 2010.[143]

Zifeng Tower ranks among the tallest buildings in the world, opened for commercial operations in 2010.[143].png) Nanjing Youth Olympic Towers

Nanjing Youth Olympic Towers

Education

The educational center of southern China for more than 1,700 years, Nanjing has a large range of prestigious higher education institutions and research institutes and a large student population. Nanjing is ranked the 88th QS Best Student City in 2019. Nanjing University is considered to be one of the top national universities nationwide. According to the QS Higher Education top-ranking university, Nanjing University is ranked the seventh university in China, and 122nd overall in the world as of 2019. Southeast University is also among the most famous universities in China and is considered to be one of the best universities for Architecture and Engineering in China. Many universities in Nanjing have satellite campuses or have moved their main campus to Xianlin University City in the eastern suburb. Some of the other biggest national universities in Nanjing are: The educational center of southern China for more than 1,700 years, the city has a large range of prestigious higher education institutions and research institutes and a large student population.

- Nanjing University

- Southeast University

- Hohai University

- Nanjing Normal University

- Nanjing Xiaozhuang University

- Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Nanjing University of Science and Technology

- Nanjing Tech University

- Nanjing Institute of Technology

- Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology

- Nanjing Audit University

- Nanjing University of Finance and Economics

- Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications

- Nanjing Agricultural University

- Nanjing Forestry University

- China Pharmaceutical University

- Nanjing Medical University

- Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine

- Nanjing Sport Institute

- Nanjing Arts Institute

- Jiangsu Second Normal University

Private universities and colleges, such as Communication University of China, Nanjing and Hopkins-Nanjing Center are also located in the city.

Some notable high schools in Nanjing are: Nanjing Foreign Language School, High School Affiliated to Nanjing Normal University, Jinling High School, Nanjing No.1 High School, Nanjing Zhonghua High School, Caulfield Grammar School (Nanjing Campus).

.jpg) Nanjing University, Gulou campus

Nanjing University, Gulou campus Nanjing University, Xianlin campus

Nanjing University, Xianlin campus Southeast University, Sipailou campus

Southeast University, Sipailou campus Nanjing Normal University, Suiyuan campus

Nanjing Normal University, Suiyuan campus

Sister cities

|

|

Notable people

- Anhua Gao, Chinese-British author

- Lei Wu, Footballer

- Xueqin Cao, Writer; Author of Dream of the Red Chamber

- Gang Tian, Mathematician; Professor at Princeton University

- Hsiao Sa, Taiwanese author

- Ni Ni, Chinese actress

- Mei Ting, Chinese actress

- Hai Qing, Chinese actress

- Pu Shu, Chinese singer-songwriter

- Xu Anqi, Chinese fencer

See also

- Jiangnan

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- Historical capitals of China

- City Wall of Nanjing

- Walled city of Nanjing

- Ming Palace

- Nanking massacre

- The Rape of Nanking (book)

- Treaty of Nanjing

- Nanjing Salted Duck

Notes

- Prior to the 1990s, Nanjing was the de jure capital of the Republic of China, though not in the Constitution of the Republic of China, with Taipei as the seat of government. This was changed with the ROC official maps from 2002 omitting such mentions of it.[1]

- Nankinese, sometimes may be translated as Nanjinese, Nanjingese, Nankingese, Nanjinger, Nankiner, etc.. In Nanjing dialect there is no difference between Nanjing and Nanjin or between Nanking and Nankin. This means the two pronunciations Jing and Jin in Mandarin Chinese pronounce the same in Nanjing dialect, and king and kin are also the same.

- In East China, in terms of urban population and urban area, the largest city is Shanghai, and the second largest is Nanjing.

- Since becoming a southern capital, the city has been called Nanking (Nanjing, 南京) unofficially, and was officially named Nanjing (Nanking) after Peking (Beijing 北京, renamed from Peping or Beiping, 北平) became a capital city during the early Ming dynasty; the name appears in Ming dynasty echo poem (蕭子顯 《奉和昭明太子鐘山講解詩》:"崇嶽基舊宇,盤嶺跨南京"), for example. It's also unofficially called Nandu (南都), and Nandu Fanhui Tu (《南都繁會圖》; 'Nandu Prosperity Picture') is an example.

- Huai (Huai of Jianghuai 江淮) is a big river north of Jiang (the river Yangtze), and the Zhe (Zhe of Jiangzhe 江浙)) is a big river south of Jiang.

- The areas covered by such geographical names as Jiangnan, Dongnan and Xiajiang are not precisely defined. In ancient times the area was known as Yangchow (揚州). Sometimes the term Jianghai (江海) is used because the region is where the Jiang (Yangtze, river) empties into the Hai (sea).

- Liuchao Gudu Bowuguan (六朝古都博物館)

- Jiangning Zhizao Bowuguan (江甯織造博物館)

- Nanjing Minsu Bowuguan (南京民俗博物館), located in Ganxi House (甘熙宅第) which is said to be the largest Chinese private house, with the nickname Ninety Nine and a Half Rooms.

- A small museum and tomb honoring the 15th century seafaring admiral Zheng He although his body was buried at sea off the Malabar Coast near Calicut in western India.[134]

- Jinling Shufa Silao Jinianguan (金陵書法四老紀念館,胡小石、林散之、蕭嫻、高二適)

References

Citations

- "Since the implementation of the Act Governing Principles for Editing Geographical Educational Texts (地理敎科書編審原則) in 1997, the guiding principle for all maps in geographical textbooks was that Taipei was to be marked as the capital with a label stating: "Location of the Central Government"". Archived from the original on 2019-11-01. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Doing Business in China – Survey" 2016年末南京市人口状况报告年末南京市人口状况综述 (in Chinese). Nanjing Bureau of Statistics. 2017-08-04. Archived from the original on 2017-10-06. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-06-15.

- OECD Urban Policy Reviews: China 2015, OECD READ edition. OECD iLibrary. OECD Urban Policy Reviews. OECD. 18 April 2015. p. 37. doi:10.1787/9789264230040-en. ISBN 9789264230033. ISSN 2306-9341. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.Linked from the OECD here Archived 2017-12-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "A Grass Roots Fight to Save a 'Super Tree'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Romanization of the Chinese Language". Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- 中国 人口数:江苏:南京市:常住 (in Chinese). CEIC. 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- 南京历史沿革 (in Chinese). Government of Nanjing. Archived from the original on 2013-06-09.

- 薛宏莉 (2008-05-07). "Archived copy" 15个副省级城市中 哈尔滨市房价涨幅排列第五名 [Prices rose in 15 sub-provincial cities, Harbin ranked fifth]. 哈尔滨地产 (in Chinese). Sohu. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-06-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 中央机构编制委员会印发《关于副省级市若干问题的意见》的通知. 中编发[1995]5号. 豆丁网 (in Chinese). 1995-02-19. Archived from the original on 2014-05-29. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- "Home – Women GP – Nanjing". Nanjing2009.fide.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- 100 National Key Universities are universities of Project 211 whose name comes from the abbreviation of 100 national key universities in the 21st century. There are 8 universities listed in Project 211 in Nanjing, 9 in Shanghai, and 23 in Beijing. According to Nature Index released in January 2018, Nanjing University is listed as one of the world top 10 universities.

- "It will come as no surprise that the top performing Chinese cities in the Nature Index are Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing. All three are significant players economically and politically, Beijing and Shanghai particularly. ... As the capital of the wealthy eastern coastal province of Jiangsu, Nanjing is located in a region rich in economic and technological activity. ..." – from "Three giants tighten their grip", Nature 528, S176–S178 (17 December 2015)

- 走马南京都市圈. 中国经济快讯周刊 (in Chinese). 2003. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03 – via people.com.cn.

- 南京介绍 (in Chinese). Xinhua News. 2012-10-09. Archived from the original on 2013-11-19.

- 江苏省行政区划介绍 (in Chinese). Jiangsu People's Government. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04.

- Rita Yi Man Li, "A Study on the Impact of Culture, Economic, History and Legal Systems Which Affect the Provisions of Fittings by Residential Developers in Boston, Hong Kong and Nanjing", Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal. 1:3–4. 2009. Access via Questia, an online subscription service.

- Crespigny 2004, 3

- 南京市. 重編囯語辭典修訂本 (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, ROC. Archived from the original on 2012-12-22. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

民國十六年,國民政府宣言定為首都,今以臺北市為我國中央政府所在地。

- Nanjing is also called Jincheng (金城, Golden City), derived from Jinling City. In addition, Jincheng was a city in Nanjing area. In the 1st year of Hsiankang in the Jin dynasty (AD 335), Langya (瑯琊), a prefectural governor Huan Wen stationed in Jincheng, submitted a proposal to establish the prefecture of South Langya in the land of Jiangsheng (江乘) county, and then the city Jincheng became the capital city of the newly established South Langya Prefecture (南瑯琊郡). The Jincheng later renamed Jinling township, in today's Qinhuai District. (《至大金陵新志》:"金城在城东二十五里,吴筑,今上元县金陵乡地名金城戍即其地。" 《至正金陵新志》:"上元縣金陵鄉,舊名金城戍。晉太元八年,謝安勞師于金城,即此。或稱琅邪城。咸康初,桓溫為琅邪內史,鎮金城。")

- 网易. 北阴阳营遗址上发现过酒器(组图)_网易新闻. news.163.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- 陶吴发现南京最大周代土墩墓(图). huaxia.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-22. Retrieved 2016-01-15.

- (金陵在春秋時本吳地,未有城邑。惟石頭城東有冶城。傳雲,夫差冶鑄於此。即今朝天宮地。) 金陵古今圖考 (Illustrated Study of Past and Present Nanjing)

- 南京的古城邑及其考古發現:金陵邑. 南京考古 (in Chinese). 30 August 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Here in Yecheng, Yuecheng and Jinling Yi, both Cheng and Yi mean city.

- 南京六朝石刻现状调查:在田野与工地间寻找国宝 (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 7 June 2006. Archived from the original on 20 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Shufen Liu, "Jiankang and the Commercial Empire of the Southern Dynasties", in Pearce, Spiro, Ebrey eds. Culture and Power, 2001:35.

- 六朝名都崛起江东. Archived copy 南京市志(第1册). Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2014-05-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 《金陵记》:"梁都之时,城中二十八万户,西至石头,东至倪塘,南至石子冈,北过蒋山,东西南北各四十里。"(in Chinese)

- Liang Baiquan (1998). Nanjing-de Liu Chao Shike (Nanjing's Six Dynasties' Sculptures). pp. 53–54. ISBN 7-80614-376-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Albert E. Dien, Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-300-07404-2. Partial text Archived 2015-09-30 at the Wayback Machine on Google Books. P. 190. A reconstruction of the original form of the ensemble is shown in Fig. 5.19.

- 梁安成康王萧秀墓石刻. Jllib.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- Sun, Cecile Chu-chin (2011). The Poetics of Repetition in English and Chinese Lyric Poetry. University of Chicago Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-226-78020-7.

- 南唐再兴金陵城. Archived copy 南京市志(第1册). Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2014-05-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Johannes L. Kurz (2011). China's Southern Tang Dynasty, 937–976. Routledge.

- Franke, Herbert (1994). "The Chin dynasty". In Twitchett, Denis; John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Tao, Jing-Shen (2009). "The Move to the South and the Reign of Kao-tsung". In Paul Jakov Smith; Denis C. Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 5, The Sung Dynasty and Its Precursors, 907–1279. Cambridge University Press. p. 647. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.

- In the 3rd year of Jianyan (1129), Jiankang became Temporary Capital (行都) of Song, being set as Eastern Capital. Although people like Yue Fei stood for the imperial court being in the city, eventually in the 8th year of Shaoxing (1139) it withdrew from Jiankang to Lin'an (present Hangzhou), and since then the city became Preserving Capital (留都) of Song dynasty.

- 隋唐州县南唐国都. Archived copy 南京市志(第1册). Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2014-05-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Yule 2002, p. 131.

- Ebrey (1999), 191.

- Fei, Si-yen (2009). Negotiating Urban Space: Urbanization and Late Ming Nanjing. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Asia Center. p. 80.

- Turnbull, Stephen R.; Steve Noon (2009). Chinese Walled Cities 221 BC-AD 1644. Osprey Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84603-381-0.

- Ansight Guides (1997). Insight Guides: China 5/E. Apa Publications. p. 268. ISBN 0-395-66287-7.

- "Largest Cities Through History". Geography.about.com. 2013-11-14. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 139–140. ISBN 9780321084439.

- Chan, Hok-lam (1998). "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-hsi, and Hsüan-te reigns, 1399–1435". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–283. ISBN 9780521243322..

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 140–141. ISBN 9780321084439..

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. p. 168. ISBN 9780321084439.

- Jonathan D. Spence. God's Chinese Son, New York 1996