Republic of China (1912–1949)

The Republic of China (ROC) was a sovereign state based in mainland China between 1912 and 1949, prior to its government's relocation to the island of Taiwan. It was established on 1 January 1912 after the Xinhai Revolution, which overthrew the Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty of China. The Republic's first president, Sun Yat-sen, served only briefly before handing over the position to Yuan Shikai, the leader of the Beiyang Army. Sun's party, the Kuomintang (KMT), then led by Song Jiaoren, won the parliamentary election held in December 1912. However, Song was assassinated on Yuan's orders shortly after; and the Beiyang Army, led by Yuan, maintained full control of the Beiyang government. Between late 1915 and early 1916, Yuan Shikai proclaimed himself Emperor of China before abdicating not long after due to popular unrest. After Yuan's death in 1916, the authority of the Beiyang government was further weakened by a brief restoration of the Qing dynasty. Cliques in the Beiyang Army claimed individual autonomy and clashed with each other during the ensuing Warlord Era.

Republic of China 中華民國 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1949 | |||||||||||||

Top: Emblem

(1913–1928) Bottom: Emblem (1928–1949) | |||||||||||||

Anthem:

Flag anthem: 《中華民國國旗歌》 "National Flag Anthem of the Republic of China" (1937–1949) | |||||||||||||

.svg.png) Location and maximum extent of territory claimed by the Republic of China (1945) | |||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||

| Largest city | Shanghai | ||||||||||||

| Official languages | Standard Chinese | ||||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | Tibetan Chagatai/Uighur Manchu Mongolian and other languages | ||||||||||||

| Official script |

| ||||||||||||

| Religion | see Religion in China | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Chinese[1] | ||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||

• 1912 | Sun Yat-sen (first, provisional) | ||||||||||||

• 1949–1950 | Li Zongren (last in Chinese mainland, acting) | ||||||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||||||

• 1912 | Tang Shaoyi (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1949 | He Yingqin (last in Chinese mainland) | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||

| National Assembly | |||||||||||||

| Legislative Yuan | |||||||||||||

| Historical era | 20th century | ||||||||||||

| 10 October 1911[lower-alpha 2]–12 February 1912[lower-alpha 3] | |||||||||||||

• Republic of China proclaimed | 1 January 1912 | ||||||||||||

• Beiyang government in Peking | 1912–1928 | ||||||||||||

• Northern Expedition | 1926–1928 | ||||||||||||

• Nationalist government in Nanking | 1927–1949 | ||||||||||||

| 1927–1936, 1946–1950[lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||

• Second Sino-Japanese War | 7 July 1937[lower-alpha 5]–2 September 1945[lower-alpha 6] | ||||||||||||

• People's Republic of China proclaimed | 1 October 1949 | ||||||||||||

• Government moved to Taipei | 7 December 1949 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1912 | 11,077,380 km2 (4,277,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1946 | 9,676,204 km2 (3,736,003 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1912 | 432,375,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1920 | 472,000,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1930 | 489,000,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1946 | 535,418,000 | ||||||||||||

• 1949 | 541,670,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 to +8:30 (Kunlun to Changpai Standard Times) | ||||||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | CN | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

Populations from http://www.populstat.info/Asia/chinac.htm | |||||||||||||

In 1921, the KMT established a rival government in Canton, supported by the fledgling Communist Party of China (CPC). The economy of northern China, overtaxed to support warlord adventurism, collapsed between 1927 and 1928. General Chiang Kai-shek, who became the KMT leader after Sun's death, started the Northern Expedition in 1926 to overthrow the Beiyang government, which was accomplished in 1928. In April 1927, Chiang established a nationalist government in Nanking, and massacred Communists in Shanghai. The latter event forced the CPC into armed rebellion, marking the beginning of the Chinese Civil War.

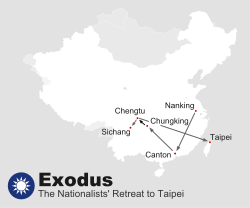

China experienced some industrialization during the 1930s but suffered conflicts between the Nationalist government in Nanking, the CPC, remaining warlords, and the Empire of Japan. Nation-building efforts yielded to fight the Second Sino-Japanese War, when the Imperial Japanese Army launched an offensive against China in 1937 which turned into a full-scale invasion. In 1946, after the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II in 1945, the Chinese Civil War between the KMT and CPC resumed, leading to the 1946 Constitution of the Republic of China replacing the 1928 Organic Law as the Republic's fundamental law. In 1949, nearing the end of the civil war, the CPC established the People's Republic of China, overthrowing the nationalist government on the Chinese mainland, with the nationalists moving their capital from Nanking to Taipei and controlling only Taiwan and other smaller islands from 1949 to the present day, and Hainan until 1950.

Names

| Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Republic of China" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chunghwa Minkuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Middle or Central State[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་ཧྭསྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghvaz Minzgoz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Дундад иргэн улс | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠢᠷᠭᠡᠨ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭخۇا مىنگو | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai irgen' gurun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The official name of the state on the mainland was the "Republic of China", but it has been known under various names throughout its existence. Shortly after the ROC's establishment in 1912, the government used the short form "China" (Zhōngguó (中國)) to refer to itself, "China" being derived from zhōng ("central" or "middle") and guó ("state, nation-state"),[lower-alpha 7] a term that developed under the Zhou dynasty in reference to its royal demesne,[lower-alpha 8] and the name was then applied to the area around Luoyi (present-day Luoyang) during the Eastern Zhou and then to China's Central Plain before being used as an occasional synonym for the state during the Qing era.[4]

"Republican China" and "Republican Era" refer to the "Beiyang government" (from 1912 to 1928), and "Nationalist government" (from 1928 to 1949).[6]

History

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | |||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BCE | |||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BCE | |||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE | |||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BCE | |||||||

| Western Zhou | |||||||

| Eastern Zhou | |||||||

| Spring and Autumn | |||||||

| Warring States | |||||||

| IMPERIAL | |||||||

| Qin 221–207 BCE | |||||||

| Han 202 BCE – 220 CE | |||||||

| Western Han | |||||||

| Xin | |||||||

| Eastern Han | |||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | |||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | |||||||

| Jin 266–420 | |||||||

| Western Jin | |||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | ||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | |||||||

| Sui 581–618 | |||||||

| Tang 618–907 | |||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | |||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | ||||||

| Song 960–1279 | |||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | ||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | |||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | |||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | |||||||

| MODERN | |||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | |||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | |||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | |||||||

Related articles

| |||||||

| History of the Republic of China (ROC) |

|---|

|

|

|

1945–present Taiwan |

|

| History of |

|

|

|

Overview

A republic was formally established on 1 January 1912 following the Xinhai Revolution, which itself began with the Wuchang Uprising on 10 October 1911, successfully overthrowing the Qing dynasty and ending over two thousand years of imperial rule in China.[7] From its founding until 1949, the republic was based on mainland China. Central authority waxed and waned in response to warlordism (1915–28), a Japanese invasion (1937–45), and a full-scale civil war (1927–49), with central authority strongest during the Nanjing Decade (1927–37), when most of China came under the control of the authoritarian, one-party military dictatorship of the Kuomintang (KMT).[8]

In 1945, at the end of World War II, the Empire of Japan surrendered control of Taiwan and its island groups to the Allies; and Taiwan was placed under the Republic of China's administrative control. The communist takeover of mainland China in 1949, after the Chinese Civil War, left the ruling Kuomintang with control over only Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and other minor islands. With the loss of the mainland, the ROC government retreated to Taiwan and the KMT declared Taipei the provisional capital.[9] Meanwhile, the Communist Party of China took over all of mainland China[10][11] and founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing.

Founding

In 1912, after over two thousand years of imperial rule, a republic was established to replace the monarchy.[7] The Qing dynasty that preceded the republic had experienced instability throughout the 19th century and suffered from both internal rebellion and foreign imperialism.[12] The ongoing instability eventually led to the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, whose attacks on foreigners resulted in the invasion by the Eight Nation Alliance. China signed the Boxer Protocol and paid a large indemnity to the foreign powers: 450 million taels of fine silver (around $333 million or £67 million at the then current exchange rates).[13] A program of institutional reform proved too little and too late. Only the lack of an alternative regime prolonged the monarchy's existence until 1912.[14][15]

The Chinese Republic grew out of the Wuchang Uprising against the Qing government, on 10 October 1911, which is now celebrated annually as the ROC's national day, also known as "Double Ten Day". On 29 December 1911, Sun Yat-sen was elected president by the Nanjing assembly, which consisted of representatives from seventeen provinces. On 1 January 1912, he was officially inaugurated and pledged "to overthrow the despotic government led by the Manchu, consolidate the Republic of China and plan for the welfare of the people".[16] Sun lacked the necessary military strength to defeat the Qing government by force. As a compromise, the new republic negotiated with Yuan Shikai the commander of the Beiyang Army , promising Yuan the presidency of the republic if he were to remove the Qing emperor by force. Yuan agreed to the deal, and the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Puyi, was forced to abdicate in 1912. Song Jiaoren led the Kuomintang Party to electoral victories by fashioning his party's program to appeal to the gentry, landowners, and merchants. Song was assassinated on March 20, 1913 at the behest of Yuan Shikai.[17]

Yuan was elected president of the ROC in 1913.[12][18] He ruled by military power and ignored the republican institutions established by his predecessor, threatening to execute Senate members who disagreed with his decisions. He soon dissolved the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) party, banned "secret organizations" (which implicitly included the KMT), and ignored the provisional constitution. An attempt at a democratic election in 1912 ended with the assassination of the elected candidate by a man recruited by Yuan. Ultimately, Yuan declared himself Emperor of China in 1915.[19] The new ruler of China tried to increase centralization by abolishing the provincial system; however, this move angered the gentry along with the provincial governors, who were usually military men. Many provinces declared independence and became warlord states. Increasingly unpopular and deserted by his supporters, Yuan abdicated in 1916 and died of natural causes shortly thereafter.[20][21] China then declined into a period of warlordism. Sun, having been forced into exile, returned to Guangdong province in the south with the help of warlords in 1917 and 1922, and set up successive rival governments to the Beiyang government in Beijing, re-establishing the KMT in October 1919. Sun's dream was to unify China by launching an expedition against the north. However, he lacked the military support and funding to turn it into a reality.[22]

Meanwhile, the Beiyang government struggled to hold onto power, and an open and wide-ranging debate evolved regarding how China should confront the West. In 1919, a student protest against the government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, considered unfair by Chinese intellectuals, led to the May Fourth movement, whose demonstrations were against the danger of spreading Western influence replacing Chinese culture. It was in this intellectual climate that the influence of Marxism spread and became popular, leading to the founding of the Communist Party of China in 1921.[23]

Nanjing decade

After Sun's death in March 1925, Chiang Kai-shek became the leader of the Kuomintang. In 1926, Chiang led the Northern Expedition with the intention of defeating the Beiyang warlords and unifying the country. Chiang received the help of the Soviet Union and the Chinese Communists. However, he soon dismissed his Soviet advisers, being convinced that they wanted to get rid of the KMT and take control.[24] Chiang decided to purge the Communists, killing thousands of them. At the same time, other violent conflicts were taking place in China: in the South, where the Communists had superior numbers, Nationalist supporters were being massacred. Such events eventually led to the Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and Communists. Chiang Kai-shek pushed the Communists into the interior and established a government, with Nanking as its capital, in 1927.[25] By 1928, Chiang's army overthrew the Beiyang government and unified the entire nation, at least nominally, beginning the so-called Nanjing Decade.

According to Sun Yat-sen's theory, the KMT was to rebuild China in three phases: a phase of military rule during which the KMT would take over power and reunite China by force; a phase of political tutelage; and finally a constitutional, democratic phase.[26] In 1930, the Nationalists, having taken power militarily and reunifying China, started the second phase, promulgating a provisional constitution and beginning the period of so-called "tutelage".[27] Criticized for instituting authoritarianism, the KMT claimed it was attempting to establish a modern democratic society. Among other things, it created the Academia Sinica, the Central Bank of China, and other agencies. In 1932, China for the first time sent a team to the Olympic Games. Campaigns were mounted and laws passed to promote the rights of women. The ease and speed of communication facilitated focusing on social problems, especially those of remote villages. The Rural Reconstruction Movement was one of many that took advantage of the new freedom to raise social consciousness. The Nationalist government published a draft constitution on 5 May 1936.[28]

During this time a series of wars took place in western China, including the Kumul Rebellion, the Sino-Tibetan War, and the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang. Although the central government was nominally in control of the entire country during this period, large areas of China remained under the semi-autonomous rule of local warlords such as Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan, provincial military leaders, or warlord coalitions. Nationalist rule was strongest in the eastern regions around the capital Nanjing. The Central Plains War in 1930, the Japanese aggression in 1931, and the Red Army's Long March in 1934 led to more power for the central government, but there continued to be foot-dragging and even outright defiance, as in the Fujian Rebellion of 1933–34.

Historians such as Edmund Fung argue that establishing a democracy in China at that time was not possible. The nation was at war and divided between Communists and Nationalists. Corruption and lack of direction within the government prevented any significant reforms from taking place. Chiang realized the lack of real work being done within his administration and told the State Council: "Our organization becomes worse and worse... many staff members just sit at their desks and gaze into space, others read newspapers and still others sleep."[29]

Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

Few Chinese had any illusions about Japanese desires on China. Hungry for raw materials and pressed by a growing population, Japan initiated the seizure of Manchuria in September 1931 and established the ex-Qing emperor Puyi as head of the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932. The loss of Manchuria, and its potential for industrial development and war industries, was a blow to the Kuomintang economy. The League of Nations, established at the end of World War I, was unable to act in the face of Japanese defiance.

The Japanese began to push south of the Great Wall into northern China and the coastal provinces. Chinese fury against Japan was predictable, but anger was also directed against Chiang and the Nanking government, which at the time was more preoccupied with anti-Communist extermination campaigns than with resisting the Japanese invaders. The importance of "internal unity before external danger" was forcefully brought home in December 1936, when Chiang Kai-shek, in an event now known as the Xi'an Incident, was kidnapped by Zhang Xueliang and forced to ally with the Communists against the Japanese in the Second Kuomintang-CCP United Front.

Chinese resistance stiffened after 7 July 1937, when a clash occurred between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Beiping (Later Beijing) near the Marco Polo Bridge. This skirmish led to open, although undeclared, warfare between China and Japan. Shanghai fell after a three-month battle during which Japan suffered extensive casualties in both its army and navy. The capital, Nanking, fell in December 1937, which was followed by mass murders and rapes known as the Nanking Massacre. The national capital was briefly at Wuhan, then removed in an epic retreat to Chongqing, the seat of government until 1945. In 1940, the Japanese set up the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime, with its capital in Nanking, which proclaimed itself the legitimate "Republic of China" in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek's government, although its claims were significantly hampered due to its being a puppet state controlling limited amounts of territory.

The United Front between the Kuomintang and the CCP had salutary effects for the beleaguered CCP, despite Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions and the rich Yangtze River Valley in central China. After 1940, conflicts between the Kuomintang and Communists became more frequent in the areas not under Japanese control. The Communists expanded their influence wherever opportunities presented themselves through mass organizations, administrative reforms and the land- and tax-reform measures favoring the peasants and, the spread of their organizational network, while the Kuomintang attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence. Meanwhile, northern China was infiltrated politically by Japanese politicians in Manchukuo using facilities such as the Wei Huang Gong.

After its entry into the Pacific War during World War II, the United States became increasingly involved in Chinese affairs. As an ally, it embarked in late 1941 on a program of massive military and financial aid to the hard-pressed Nationalist Government. In January 1943, both the United States and the United Kingdom led the way in revising their unequal treaties with China from the past.[30][31] Within a few months a new agreement was signed between the United States and the Republic of China for the stationing of American troops in China as part of the common war effort against Japan. The United States sought unsuccessfully to reconcile the rival Kuomintang and Communists, to make for a more effective anti-Japanese war effort. In December 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1880s, and subsequent laws, enacted by the United States Congress to restrict Chinese immigration into the United States were repealed. The wartime policy of the United States was meant to help China become a strong ally and a stabilizing force in postwar East Asia. During the war, China was one of the Big Four Allies of World War II and later one of the Four Policemen, which was a precursor to China having a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.[32]

In August 1945, with American help, Nationalist troops moved to take the Japanese surrender in North China. The Soviet Union—encouraged to invade Manchuria to hasten the end of the war and allowed a Soviet sphere of influence there as agreed to at the Yalta Conference in February 1945—dismantled and removed more than half the industrial equipment left there by the Japanese. Although the Chinese had not been present at Yalta, they had been consulted and had agreed to have the Soviets enter the war, in the belief that the Soviet Union would deal only with the Kuomintang government. However, the Soviet presence in northeast China enabled the Communists to arm themselves with equipment surrendered by the withdrawing Japanese army.

Post-World War II

In 1945, after the end of the war, the Nationalist Government moved back to Nanjing. The Republic of China emerged from the war nominally a great military power but actually a nation economically prostrate and on the verge of all-out civil war. The problems of rehabilitating the formerly Japanese-occupied areas and of reconstructing the nation from the ravages of a protracted war were staggering. The economy deteriorated, sapped by the military demands of foreign war and internal strife, by spiraling inflation, and by Nationalist profiteering, speculation, and hoarding. Starvation came in the wake of the war, and millions were rendered homeless by floods and unsettled conditions in many parts of the country.

On 25 October 1945, following the Surrender of Japan, the administration of Taiwan was handed over from Japan to the Republic of China.[33] After the end of the war, United States Marines were used to hold Beiping (Beijing) and Tianjin against a possible Soviet incursion, and logistic support was given to Kuomintang forces in north and northeast China. To further this end, on 30 September 1945 the 1st Marine Division, charged with maintaining security in the areas of the Shandong Peninsula and the eastern Hebei province, arrived in China.[34]

In January 1946, through the mediation of the United States, a military truce between the Kuomintang and the Communists was arranged, but battles soon resumed. Public opinion of the administrative incompetence of the Nationalist government was incited by the Communists during the nationwide student protest against the mishandling of the Shen Chong rape case in early 1947 and during another national protest against monetary reforms later that year. Realizing that no American efforts short of large-scale armed intervention could stop the coming war, in early 1947 the United States withdrew the American mission, headed by Gen. George Marshall. The Chinese Civil War became more widespread; battles raged not only for territories but also for the allegiance of sections of the population. The United States aided the Nationalists with massive economic loans and weapons but no combat support.

Belatedly, the Republic of China government sought to enlist popular support through internal reforms. However, the effort was in vain, because of rampant government corruption and the accompanying political and economic chaos. By late 1948 the Kuomintang position was bleak. The demoralized and undisciplined National Revolutionary Army proved to be no match for the Communists' motivated and disciplined People's Liberation Army. The Communists were well established in the north and northeast. Although the Kuomintang had an advantage in numbers of men and weapons, controlled a much larger territory and population than their adversaries, and enjoyed considerable international support, they were exhausted by the long war with Japan and in-fighting among various generals. They were also losing the propaganda war to the Communists, with a population weary of Kuomintang corruption and yearning for peace.

In January 1949, Beiping was taken by the Communists without a fight, and its name changed back to Beijing. Following the capture of Nanjing on 23 April, major cities passed from Kuomintang to Communist control with minimal resistance, through November. In most cases the surrounding countryside and small towns had come under Communist influence long before the cities. Finally, on 1 October 1949, Communists led by Mao Zedong founded the People's Republic of China. Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law in May 1949, whilst a few hundred thousand Nationalist troops and two million refugees, predominantly from the government and business community, fled from mainland China to Taiwan. There remained in China itself only isolated pockets of resistance. On 7 December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei, Taiwan, the temporary capital of the Republic of China.

During the Chinese Civil War both the Nationalists and Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants killed by both sides.[35] Benjamin Valentino has estimated atrocities in the civil war resulted in the death of between 1.8 million and 3.5 million people between 1927 and 1949, including deaths from forced conscription and massacres.[36]

Government

The first Republic of China national government was established on 1 January 1912, in Nanjing, and was founded on the Constitution of the ROC and its Three Principles of the People, which state that "[the ROC] shall be a democratic republic of the people, to be governed by the people and for the people."[37]

Sun Yat-sen was the provisional president. Delegates from the provinces sent to confirm the government's authority formed the first parliament in 1913. The power of this government was limited, with generals controlling both the central and northern provinces of China, and short-lived. The number of acts passed by the government was few and included the formal abdication of the Qing dynasty and some economic initiatives. The parliament's authority soon became nominal: violations of the Constitution by Yuan were met with half-hearted motions of censure. Kuomintang members of parliament who gave up their membership in the KMT were offered 1,000 pounds. Yuan maintained power locally by sending generals to be provincial governors or by obtaining the allegiance of those already in power.

When Yuan died, the parliament of 1913 was reconvened to give legitimacy to a new government. However, the real power passed to military leaders, leading to the warlord period. The impotent government still had its use; when World War I began, several Western powers and Japan wanted China to declare war on Germany, in order to liquidate German holdings in China.

In February 1928, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 2nd Kuomintang National Congress, held in Nanjing, passed the Reorganization of the Nationalist Government Act. This act stipulated that the Nationalist Government was to be directed and regulated under the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, with the Committee of the Nationalist Government being elected by the KMT Central Committee. Under the Nationalist Government were seven ministries – Interior, Foreign Affairs, Finance, Transport, Justice, Agriculture and Mines, and Commerce, in addition to institutions such as the Supreme Court, Control Yuan, and the General Academy.

.jpg)

With the promulgation of the Organic Law of the Nationalist Government in October 1928, the government was reorganized into five different branches, or yuan, namely the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Examination Yuan as well as the Control Yuan. The Chairman of the National Government was to be the head-of-state and commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army. Chiang Kai-shek was appointed as the first Chairman, a position he would retain until 1931. The Organic Law also stipulated that the Kuomintang, through its National Congress and Central Executive Committee, would exercise sovereign power during the period of "political tutelage", that the KMT's Political Council would guide and superintend the Nationalist Government in the execution of important national affairs, and that the Political Council has the power to interpret or amend the Organic Law.[38]

Shortly after the Second Sino-Japanese War, a long-delayed constitutional convention was summoned to meet in Nanking in May 1946. Amidst heated debate, this convention adopted many constitutional amendments demanded by several parties, including the KMT and the Communist Party, into the Constitution. This Constitution was promulgated on 25 December 1946 and came into effect on 25 December 1947. Under it, the Central Government was divided into the presidency and the five yuans, each responsible for a part of the government. None was responsible to the other except for certain obligations such as the president appointing the head of the Executive Yuan. Ultimately, the president and the yuans reported to the National Assembly, which represented the will of the citizens.

Under the new constitution the first elections for the National Assembly occurred in January 1948, and the Assembly was summoned to meet in March 1948. It elected the President of the Republic on 21 March 1948, formally bringing an end to the KMT party rule started in 1928, although the President was a member of the KMT. These elections, though praised by at least one US observer, were poorly received by the Communist Party, which would soon start an open, armed insurrection.

Foreign relations

Before the Nationalist government was ousted from the mainland, the Republic of China had diplomatic relations with 59 countries, such as Australia, Canada, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, France, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Panama, Siam, Soviet Union, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vatican City. Most of these relations continued at least until the 1970s, and the Republic of China remained a member of the United Nations until 1971.

Administrative divisions

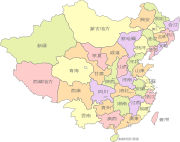

Rand McNally map of the Republic of China in 1914, when Mongolia declared its independence

Rand McNally map of the Republic of China in 1914, when Mongolia declared its independence Map of provinces and equivalents of the Republic of China in law (1945)

Map of provinces and equivalents of the Republic of China in law (1945)

| Provinces and Equivalents of the Republic of China (1945)[39] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period Name (Current Name) | Traditional Chinese | Pinyin | Abbreviation | Capital | Chinese | Modern equivalent (if applicable) |

| Provinces | ||||||

| Antung (Andong) | 安東 | Āndōng | 安 ān | Tunghwa (Tonghua) | 通化 | Now part of Jilin and Liaoning |

| Anhwei (Anhui) | 安徽 | Ānhuī | 皖 wǎn | Hofei (Hefei) | 合肥 | |

| Chahar (Chahar) | 察哈爾 | Cháhār | 察 chá | Changyuan (Zhangjiakou) | 張垣(張家口) | Now part of Inner Mongolia and Hebei |

| Chekiang (Zhejiang) | 浙江 | Zhèjiāng | 浙 zhè | Hangchow (Hangzhou) | 杭州 | |

| Fukien (Fujian) | 福建 | Fújiàn | 閩 mǐn | Foochow (Fuzhou) | 福州 | |

| Hopeh (Hebei) | 河北 | Héběi | 冀 jì | Tsingyuan (Baoding) | 清苑(保定) | |

| Heilungkiang (Heilongjiang) | 黑龍江 | Hēilóngjiāng | 黑 hēi | Peian (Bei'an) | 北安 | |

| Hokiang (Hejiang) | 合江 | Héjiāng | 合 hé | Chiamussu (Jiamusi) | 佳木斯 | Now part of Heilongjiang |

| Honan (Henan) | 河南 | Hénán | 豫 yù | Kaifeng (Kaifeng) | 開封 | |

| Hupeh (Hubei) | 湖北 | Húběi | 鄂 è | Wuchang (Wuchang) | 武昌 | |

| Hunan (Hunan) | 湖南 | Húnán | 湘 xiāng | Changsha (Changsha) | 長沙 | |

| Hsingan (Xing'an) | 興安 | Xīng'ān | 興 xīng | Hailar (Hulunbuir) | 海拉爾(呼倫貝爾) | Now part of Heilongjiang and Jilin |

| Jehol (Rehe) | 熱河 | Rèhé | 熱 rè | Chengteh (Chengde) | 承德 | Now part of Hebei, Liaoning, and Inner Mongolia |

| Kansu (Gansu) | 甘肅 | Gānsù | 隴 lǒng | Lanchow (Lanzhou) | 蘭州 | |

| Kiangsu (Jiangsu) | 江蘇 | Jiāngsū | 蘇 sū | Chingkiang (Zhenjiang) | 鎮江 | |

| Kiangsi (Jiangxi) | 江西 | Jiāngxī | 贛 gàn | Nanchang (Nanchang) | 南昌 | |

| Kirin (Jilin) | 吉林 | Jílín | 吉 jí | Kirin (Jilin) | 吉林 | |

| Kwangtung (Guangdong) | 廣東 | Guǎngdōng | 粵 yuè | Canton (Guangzhou) | 廣州 | |

| Kwangsi (Guangxi) | 廣西 | Guǎngxī | 桂 guì | Kweilin (Guilin) | 桂林 | |

| Kweichow (Guizhou) | 貴州 | Guìzhōu | 黔 qián | Kweiyang (Guiyang) | 貴陽 | |

| Liaopeh (Liaobei) | 遼北 | Liáoběi | 洮 táo | Liaoyuan (Liaoyuan) | 遼源 | Now mostly part of Inner Mongolia |

| Liaoning (Liaoning) | 遼寧 | Liáoníng | 遼 liáo | Shenyang (Shenyang) | 瀋陽 | |

| Ningsia (Ningxia) | 寧夏 | Níngxià | 寧 níng | Yinchuan (Yinchuan) | 銀川 | |

| Nunkiang (Nenjiang) | 嫩江 | Nènjiāng | 嫩 nèn | Tsitsihar (Qiqihar) | 齊齊哈爾 | The province was abolished in 1950 and incorporated with Heilongjiang province. |

| Shansi (Shanxi) | 山西 | Shānxī | 晉 jìn | Taiyuan (Taiyuan) | 太原 | |

| Shantung (Shandong) | 山東 | Shāndōng | 魯 lǔ | Tsinan (Jinan) | 濟南 | |

| Shensi (Shaanxi) | 陝西 | Shǎnxī | 陝 shǎn | Sian (Xi'an) | 西安 | |

| Sikang (Xikang) | 西康 | Xīkāng | 康 kāng | Kangting (Kangding) | 康定 | Now part of Tibet and Sichuan |

| Sinkiang (Xinjiang) | 新疆 | Xīnjiāng | 新 xīn | Tihwa (Ürümqi) | 迪化(烏魯木齊) | |

| Suiyuan (Suiyuan) | 綏遠 | Suīyuǎn | 綏 suī | Kweisui (Hohhot) | 歸綏(呼和浩特) | Now part of Inner Mongolia |

| Sungkiang (Songjiang) | 松江 | Sōngjiāng | 松 sōng | Mutankiang (Mudanjiang) | 牡丹江 | Now part of Heilongjiang |

| Szechwan (Sichuan) | 四川 | Sìchuān | 蜀 shǔ | Chengtu (Chengdu) | 成都 | |

| Taiwan (Taiwan) | 臺灣 | Táiwān | 臺 tái | Taipei | 臺北 | |

| Tsinghai (Qinghai) | 青海 | Qīnghǎi | 青 qīng | Sining (Xining) | 西寧 | |

| Yunnan (Yunnan) | 雲南 | Yúnnán | 滇 diān | Kunming (Kunming) | 昆明 | |

| Special Administrative Region | ||||||

| Hainan (Hainan) | 海南 | Hǎinán | 瓊 qióng | Haikow (Haikou) | 海口 | |

| Regions | ||||||

| Mongolia Area (Outer Mongolia) | 蒙古 | Ménggǔ | 蒙 méng | Kulun (now Ulaanbaatar) | 庫倫 | Now part of the State of Mongolia. As the successor of the Qing dynasty, the Nationalist government claimed Outer Mongolia, and for a short time under the Beiyang government occupied it. The Nationalist government recognised Mongolia's independence in the 1945 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship due to pressure from the Soviet Union but that recognition was rescinded in 1953 during the Cold War.[40] |

| Tibet Area (Tibet) | 西藏 | Xīzàng | 藏 zàng | Lhasa | 拉薩 | |

| Special Municipalities | ||||||

| Nanking (Nanjing) | 南京 | Nánjīng | 京 jīng | (Chinhuai District) | 秦淮區 | |

| Shanghai (Shanghai) | 上海 | Shànghǎi | 滬 hù | (Huangpu District) | 黄浦區 | |

| Peiping or Peking (Beijing) | 北平 | Běipíng | 平 píng | (Xicheng District) | 西城區 | |

| Tientsin (Tianjin) | 天津 | Tiānjīn | 津 jīn | (Heping District) | 和平區 | |

| Chungking (Chongqing) | 重慶 | Chóngqìng | 渝 yú | (Yuzhong District) | 渝中區 | |

| Hankow (Hankou, Wuhan) | 漢口 | Hànkǒu | 漢 hàn | (Jiang'an District) | 江岸區 | |

| Canton (Guangzhou) | 廣州 | Guǎngzhōu | 穗 suì | (Yuexiu District) | 越秀區 | |

| Sian (Xi'an) | 西安 | Xī'ān | 安 ān | (Weiyang District) | 未央區 | |

| Tsingtao (Qingdao) | 青島 | Qīngdǎo | 膠 jiāo | (Shinan District) | 市南區 | |

| Dairen (Dalian) | 大連 | Dàlián | 連 lián | (Xigang District) | 西崗區 | |

| Mukden (Shenyang) | 瀋陽 | Shěnyáng | 瀋 shěn | (Shenhe District) | 瀋河區 | |

| Harbin (Harbin) | 哈爾濱 | Hā'ěrbīn | 哈 hā | (Nangang District) | 南崗區 | |

Military

The military power of the Republic of China was inherited from the New Army, mainly the Beiyang Army, which later split into many factions and attacked each other.[41] The National Revolutionary Army was established by Sun Yat-sen in 1925 in Guangdong with the goal of reunifying China under the Kuomintang. Originally organized with Soviet aid as a means for the KMT to unify China against warlordism, the National Revolutionary Army fought many major engagements: in the Northern Expedition against Beiyang Army warlords, in the Second Sino-Japanese War against the Imperial Japanese Army, and in the Chinese Civil War against the People's Liberation Army.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the armed forces of the Communist Party of China were nominally incorporated into the National Revolutionary Army, while remaining under separate command, but broke away to form the People's Liberation Army shortly after the end of the war. With the promulgation of the Constitution of the Republic of China in 1947 and the formal end of the KMT party-state, the National Revolutionary Army was renamed the Republic of China Armed Forces, with the bulk of its forces forming the Republic of China Army, which retreated to Taiwan in 1949 after their defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Units which surrendered and remained in mainland China were either disbanded or incorporated into the People's Liberation Army.[42]

Economy

In the early years of the Republic of China, the economy remained unstable as the country was marked by constant warfare between different regional warlord factions. The Beiyang government in Beijing experienced constant changes in leadership, and this political instability led to stagnation in economic development until Chinese reunification in 1928 under the Kuomintang.[43] After this reunification, China entered a period of relative stability—despite ongoing isolated military conflicts and in the face of Japanese aggression in Shandong and Manchuria, in 1931—a period known as the "Nanjing Decade".

Chinese industries grew considerably from 1928 to 1931. While the economy was hit by the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931 and the Great Depression from 1931 to 1935, industrial output recovered to their earlier peak by 1936. This is reflected by the trends in Chinese GDP. In 1932, China's GDP peaked at 28.8 billion, before falling to 21.3 billion by 1934 and recovering to 23.7 billion by 1935.[44] By 1930, foreign investment in China totaled 3.5 billion, with Japan leading (1.4 billion) followed by the United Kingdom (1 billion). By 1948, however, the capital investment had halted and dropped to only 3 billion, with the US and Britain being the leading investors.[45]

However, the rural economy was hit hard by the Great Depression of the 1930s, in which an overproduction of agricultural goods lead to falling prices for China as well as an increase in foreign imports (as agricultural goods produced in western countries were "dumped" in China). In 1931, Chinese imports of rice amounted to 21 million bushels compared with 12 million in 1928. Other imports saw even more increases. In 1932, 15 million bushels of grain were imported compared with 900,000 in 1928. This increased competition lead to a massive decline in Chinese agricultural prices and thus the income of rural farmers. In 1932, agricultural prices were at 41 percent of 1921 levels.[46] By 1934, rural incomes had fallen to 57 percent of 1931 levels in some areas.[46]

In 1937, Japan invaded China and the resulting warfare laid waste to China. Most of the prosperous east coast was occupied by the Japanese, who committed atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre. In one anti-guerilla sweep in 1942, the Japanese killed up to 200,000 civilians in a month. The war was estimated to have killed between 20 and 25 million Chinese, and destroyed all that Chiang had built up in the preceding decade.[47] Development of industries was severely hampered after the war by devastating civil conflict as well as the inflow of cheap American goods. By 1946, Chinese industries operated at 20% capacity and had 25% of the output of pre-war China.[48]

One effect of the war with Japan was a massive increase in government control of industries. In 1936, government-owned industries were only 15% of GDP. However, the ROC government took control of many industries in order to fight the war. In 1938, the ROC established a commission for industries and mines to supervise and control firms, as well as instilling price controls. By 1942, 70% of Chinese industry was owned by the government.[49]

Following the war with Japan, Chiang acquired Taiwan from Japan and renewed his struggle with the communists. However, the corruption of the KMT, as well as hyperinflation as a result of trying to fight the civil war, resulted in mass unrest throughout the Republic[50] and sympathy for the communists. In addition, the communists' promise to redistribute land gained them support among the large rural population. In 1949, the communists captured Beijing and later Nanjing. The People's Republic of China was proclaimed on 1 October 1949. The Republic of China relocated to Taiwan where Japan had laid an educational groundwork.[51]

See also

- Economic history of China (1912–49)

- Five Races Under One Union

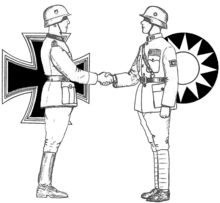

- Sino-German cooperation 1926–1941

- Sino-Soviet relations

- Three Principles of the People

Notes

- as wartime provisional capital during the Second Sino-Japanese War

- Wuchang Uprising started.

- The last monarch of the Qing dynasty, Xuantong Emperor abdicated, Qing dynasty formally ended.

- Chinese Communist Revolution.

- Marco Polo Bridge Incident started.

- Surrender of Japan at the end of World War II.

- Although this is the present meaning of guó, in Old Chinese (when its pronunciation was something like /*qʷˤək/)[3] it meant the walled city of the Chinese and the areas they could control from them.[4]

- Its use is attested from the 6th-century Classic of History, which states "Huangtian bestowed the lands and the peoples of the central state to the ancestors" (皇天既付中國民越厥疆土于先王).[5]

References

Citations

- Dreyer, June Teufel (17 July 2003). The Evolution of a Taiwanese National Identity. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Bilik, Naran (2015), "Reconstructing China beyond Homogeneity", Patriotism in East Asia, Political Theories in East Asian Context, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 105

- Baxter-Sagart.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese History: A Manual, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph No. 52, Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, p. 132, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4

- 《尚書》, 梓材. (in Chinese)

- Wright (2018).

- China, Fiver thousand years of History and Civilization. City University Of Hong Kong Press. 2007. p. 116. ISBN 9789629371401. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Roy, Denny (2004). Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 55, 56. ISBN 0-8014-8805-2.

- "Taiwan Timeline – Retreat to Taiwan". BBC News. 2000. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- China: U.S. policy since 1945. Congressional Quarterly. 1980. ISBN 0-87187-188-2.

the city of Taipei became the temporary capital of the Republic of China

- "Introduction to Sovereignty: A Case Study of Taiwan". Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "The Chinese Revolution of 1911". US Department of State. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Spence, Jonathan D. [1991] (1991), The Search for Modern China, WW Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-30780-8.

- Fenby 2009, pp. 89–94

- Fairbank; Goldman. China. p. 235. ISBN 0-690-07612-6.

- "孙中山任临时大总统誓词手迹". people.com.

- Jonathan Fenby, "The silencing of Song." History Today (March 2013( 63#3 pp 5-7.

- Fenby 2009, pp. 123–125

- Fenby 2009, p. 131

- Fenby 2009, pp. 136–138

- Meyer, Kathryn; James H Wittebols; Terry Parssinen (2002). Webs of Smoke. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 54–56. ISBN 0-7425-2003-X.

- Pak, Edwin; Wah Leung (2005). Essentials of Modern Chinese History. Research & Education Assoc. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-87891-458-6.

- Guillermaz, Jacques (1972). A History of the Chinese Communist Party 1921–1949. Taylor & Francis. pp. 22–23.

- Fenby 2009

- "民國十六年,國民政府宣言定為首都,今以臺北市為我國中央政府所在地。". Ministry of Education, ROC. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- Edmund S. K. Fung. In Search of Chinese Democracy: Civil Opposition in Nationalist China, 1929–1949 (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0521771242), p. 30.

- Chen, Lifu; Ramon Hawley Myers (1994). Hsu-hsin Chang, Ramon Hawley Myers (ed.). The storm clouds clear over China: the memoir of Chʻen Li-fu, 1900–1993. Hoover Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-8179-9272-3.

After the 1930 mutiny ended, Chiang accepted the suggestion of Wang Ching-wei, Yen Hsi-shan, and Feng Yü-hsiang that a provisional constitution for the political tutelage period be drafted.

- Jing Zhiren (荆知仁). 中华民国立宪史 (in Chinese). 联经出版公司.

- (Fung 2000, p. 5) "Nationalist disunity, political instability, civil strife, the communist challenge, the autocracy of Chiang Kai-shek, the ascendancy of the military, the escalating Japanese threat, and the "crisis of democracy" in Italy, Germany, Poland, and Spain, all contributed to a freezing of democracy by the Nationalist leadership."

- Sino-U.S. Treaty for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China

- Sino-British Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China

- Urquhart, Brian. Looking for the Sheriff. New York Review of Books, 16 July 1998.

- Brendan M. Howe (2016). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 9781317077404.

- Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945–1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- Rummel, Rudolph (1994), Death by Government.

- Valentino, Benjamin A. Final solutions: mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century Cornell University Press. 8 December 2005. p88

- "The Republic of China Yearbook 2008 / CHAPTER 4 Government". Government Information Office, Republic of China (Taiwan). 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Wilbur, Clarence Martin. The Nationalist Revolution in China, 1923–1928. Cambridge University Press, 1983, p. 190.

- National Institute for Compilation and Translation of the Republic of China (Taiwan): Geography Textbook for Junior High School Volume 1 (1993 version): Lesson 10: pp. 47–49.

- 1945年「外モンゴル独立公民投票」をめぐる中モ外交交渉 (in Japanese).

- Schillinger, Nicolas (2016). The Body and Military Masculinity in Late Qing and Early Republican China: The Art of Governing Soldiers. Lexington Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-1498531689.

- Westad, Odd (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8047-4484-3.

last major GMD stronghold.

- Sun Jian, pages 613–614

- Sun Jian, pg 1059–1071

- Sun Jian, pg 1353

- Sun Jian, page 1089

- Sun Jian, page 615-616

- Sun Jian, page 1319

- Sun Jian, pg 1237–1240

- Sun Jian, page 617-618

- Gary Marvin Davison. A short history of Taiwan: the case for independence. Praeger Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 0-275-98131-2.

Basic literacy came to most of the school-aged populace by the end of the Japanese tenure on Taiwan. School attendance for Taiwanese children rose steadily throughout the Japanese era, from 3.8 percent in 1904 to 13.1 percent in 1917; 25.1 percent in 1920; 41.5 percent in 1935; 57.6 percent in 1940; and 71.3 percent in 1943.

Sources

For works on specific people and events, please see the relevant articles.

- Fenby, Jonathan (2009). The Penguin History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power, 1850-2008. London: Penguin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrison, Henrietta (2001). China. London: Arnold; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0340741333.. In the series "Inventing the Nation."

- Jowett, Philip. (2013) China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894–1949 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013).

- Leung, Edwin Pak-wah. Historical Dictionary of Revolutionary China, 1839-1976 (1992) online free to borrow

- Leung, Edwin Pak-wah. Political Leaders of Modern China: A Biographical Dictionary (2002)

- Li, Xiaobing. (2007) A History of the Modern Chinese Army excerpt

- Li, Xiaobing. (2012) China at War: An Encyclopedia excerpt

- Mitter, Rana (2004). A Bitter Revolution: China's Struggle with the Modern World. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192803417.

- George F. Botjer (1979). A short history of Nationalist China, 1919-1949. Putnam. p. 180.

- Sheridan, James E. (1975). China in Disintegration : The Republican Era in Chinese History, 1912-1949. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0029286107.

- Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674033382.

- van de Ven, Hans (2017). China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China, 1937-1952. London: Profile Books Limited. ISBN 9781781251942.

- Vogel, Ezra F. China and Japan: Facing History (2019) excerpt

- Westad, Odd Arne. Restless Empire: China and the World since 1750 (2012) Online free to borrow

Historiography and bibliography

- Wright, Tim (2018). Republican China, 1911–1949. Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199920082-0028.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

.svg.png)