Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen[note 1] (/ˈsʌn ˈjætˈsɛn/; born Sun Wen; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)[1][2] was a Chinese philosopher, physician, and politician, who served as the provisional first president of the Republic of China and the first leader of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party of China). He is referred as the "Father of the Nation" in the Republic of China for his instrumental role in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty during the Xinhai Revolution. Sun is unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for being widely revered in both mainland China and Taiwan.[3]

Sun Yat-sen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sun Yat-Sen in the 1910s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Provisional President of the Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 January 1912 – 10 March 1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Li Yuanhong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Puyi (Emperor of China) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Yuan Shikai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier of the Kuomintang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 October 1919 – 12 March 1925 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Zhang Renjie (as chairman) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Sun Wen (孫文) 12 November 1866 Cuiheng, Guangdong, Qing Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 12 March 1925 (aged 58) Beijing, Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, Nanjing, Jiangsu, People's Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Kuomintang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | Chinese Revolutionary Party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Lu Muzhen (m. 1885; div. 1915) Kaoru Otsuki (m. 1903–1906) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic partner | Chen Cuifen (concubine) (1892–1925) Haru Asada (concubine)(1897–1902) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Sun Fo Sun Yan Sun Wan Fumiko Miyagawa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Lady Yang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Sun Dacheng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (MD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Philosopher, physician, politician | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature (Chinese) |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1917–1925 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Grand Marshal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sun Yat-sen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孫逸仙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孙逸仙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sun Zhongshan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孫中山 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孙中山 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zaizhi (courtesy name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 載之 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sun Wen (birth name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孫文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孙文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sun is considered to be one of the greatest leaders of modern China, but his political life was one of constant struggle and frequent exile. After the success of the revolution in which Han Chinese regained power after 268 years of living under the Manchu Qing dynasty, he quickly resigned as President of the newly founded Republic of China and relinquished it to Yuan Shikai. He soon went to exile in Japan for safety but returned to found a revolutionary government in the South as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. In 1923, he invited representatives of the Communist International to Canton to re-organize his party and formed a brittle alliance with the Chinese Communist Party. He did not live to see his party unify the country under his successor, Chiang Kai-shek in the Northern Expedition. He died in Beijing of gallbladder cancer on 12 March 1925.[4]

Sun's chief legacy is his political philosophy known as the Three Principles of the People: Mínzú (民族主義, Mínzú Zhǔyì) or nationalism (independence from foreign imperialist domination), Mínquán (民權主義, Mínquán Zhǔyì) or "rights of the people" (sometimes translated as "democracy"), and Mínshēng (民生主義, Mínshēng Zhǔyì) or people's livelihood (sometimes translated as "welfare", or literally "a scientific study of helping people to survive in the society," as he explained the difference between welfare and Karl Marx's socialism in his book).[5][6][7]

Names

Sun was born as Sun Wen (Cantonese: Syūn Màhn; 孫文), and his genealogical name was Sun Deming (Syūn Dāk-mìhng; 孫德明).[1][8] As a child, his pet name was Tai Tseung (Dai-jeuhng; 帝象).[1] Sun's courtesy name was Zaizhi (Jai-jī; 載之), and his baptized name was Rixin (Yaht-sān; 日新).[9] While at school in Hong Kong he got the art name Yat-sen (Chinese: 逸仙; pinyin: Yìxiān).[10] Sūn Zhōngshān (孫中山), the most popular of his Chinese names, is derived from his Japanese name Nakayama Shō (中山樵), the pseudonym given to him by Tōten Miyazaki while in hiding in Japan.[1]

Early years

Birthplace and early life

Sun Wen was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng and Madame Yang.[2] His birthplace was the village of Cuiheng, Xiangshan County (now Zhongshan City), Guangdong.[2] He had a cultural background of Hakka[11][12] and Cantonese. His father owned very little land and worked as a tailor in Macau, and as a journeyman and a porter.[13] After finishing primary education, he moved to Honolulu in the Kingdom of Hawaii, where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brother Sun Mei.[14][15][16][17]

Education years

At the age of 10, Sun began seeking schooling,[1] and he met childhood friend Lu Haodong.[1] By age 13 in 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, Sun went to live with his elder brother, Sun Mei (孫眉) in Honolulu.[1] Sun Mei financed Sun Yat-sen's education and would later be a major contributor for the overthrow of the Manchus.[14][15][16][17]

During his stay in Honolulu, Sun Yat-sen went to ʻIolani School where he studied English, British history, mathematics, science, and Christianity.[1] While he was originally unable to speak English, Sun Yat-sen quickly picked up the language and received a prize for academic achievement from King David Kalākaua before graduating in 1882.[18] He then attended Oahu College (now known as Punahou School) for one semester.[1][19] In 1883 he was sent home to China as his brother was becoming worried that Sun Yat-sen was beginning to embrace Christianity.[1]

When he returned to China in 1883 at age 17, Sun met up with his childhood friend Lu Haodong again at Beijidian (北極殿), a temple in Cuiheng Village.[1] They saw many villagers worshipping the Beiji (literally North Pole) Emperor-God in the temple, and were dissatisfied with their ancient healing methods.[1] They broke the statue, incurring the wrath of fellow villagers, and escaped to Hong Kong.[1][20][21] While in Hong Kong in 1883 he studied at the Diocesan Boys' School, and from 1884 to 1886 he was at The Government Central School.[22]

In 1886 Sun studied medicine at the Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the Christian missionary John G. Kerr.[1] Ultimately, he earned the license of Christian practice as a medical doctor from the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of The University of Hong Kong) in 1892.[1][10] Notably, of his class of 12 students, Sun was one of the only two who graduated.[23][24][25]

Religious views and Christian baptism

In the early 1880s, Sun Mei sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of British Anglicans and directed by an Anglican prelate named Alfred Willis. The language of instruction was English. Although Bishop Willis emphasized that no one was forced to accept Christianity, the students were required to attend chapel on Sunday. At Iolani School, young Sun Wen first came in contact with Christianity. In his work, Schriffin speculated that Christianity was to have a great influence on Sun's whole future political life.[26]

Sun was later baptized in Hong Kong (on 4 May 1884) by Rev. C. R. Hager[27][28][29] an American missionary of the Congregational Church of the United States (ABCFM) to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.[30][31] Sun attended To Tsai Church (道濟會堂), founded by the London Missionary Society in 1888,[32] while he studied Western Medicine in Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese. Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the Christian church. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.[31]

Transformation into a revolutionary

Four Bandits

During the Qing-dynasty rebellion around 1888, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers who were nicknamed the Four Bandits at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese.[33] Sun, who had grown increasingly frustrated by the conservative Qing government and its refusal to adopt knowledge from the more technologically advanced Western nations, quit his medical practice in order to devote his time to transforming China.

Furen and Revive China Society

In 1891, Sun met revolutionary friends in Hong Kong including Yeung Ku-wan who was the leader and founder of the Furen Literary Society.[34] The group was spreading the idea of overthrowing the Qing. In 1894, Sun wrote an 8,000 character petition to Qing Viceroy Li Hongzhang presenting his ideas for modernizing China.[35][36][37] He traveled to Tianjin to personally present the petition to Li but was not granted an audience.[38] After this experience, Sun turned irrevocably toward revolution. He left China for Hawaii and founded the Revive China Society, which was committed to revolutionizing China's prosperity. Members were drawn mainly from Chinese expatriates, especially the lower social classes. The same month in 1894 the Furen Literary Society was merged with the Hong Kong chapter of the Revive China Society.[34] Thereafter, Sun became the secretary of the newly merged Revive China society, which Yeung Ku-wan headed as president.[39] They disguised their activities in Hong Kong under the running of a business under the name "Kuen Hang Club"[40]:90 (乾亨行).[41]

First Sino-Japanese War

In 1895, China suffered a serious defeat during the First Sino-Japanese War. There were two types of responses. One group of intellectuals contended that the Manchu Qing government could restore its legitimacy by successfully modernizing.[42] Stressing that overthrowing the Manchu would result in chaos and would lead to China being carved up by imperialists, intellectuals like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao supported responding with initiatives like the Hundred Days' Reform.[42] In another faction, Sun Yat-sen and others like Zou Rong wanted a revolution to replace the dynastic system with a modern nation-state in the form of a republic.[42] The Hundred Days' reform turned out to be a failure by 1898.[43]

From uprising to exile

First Guangzhou uprising

In the second year of the establishment of the Revive China society on 26 October 1895, the group planned and launched the First Guangzhou uprising against the Qing in Guangzhou.[36] Yeung Ku-wan directed the uprising starting from Hong Kong.[39] However, plans were leaked out and more than 70 members, including Lu Haodong, were captured by the Qing government. The uprising was a failure. Sun received financial support mostly from his brother who sold most of his 12,000 acres of ranch and cattle in Hawaii.[14] Additionally, members of his family and relatives of Sun would take refuge at the home of his brother Sun Mei at Kamaole in Kula, Maui.[14][15][16][17][44]

Exile in Japan

Sun Yat-sen spent time living in Japan while in exile. He was supported by the Japanese politician Tōten Miyazaki. Most Japanese who actively worked with Sun were motivated by a pan-Asian fear of encroaching Western imperialism.[45] While in Japan, Sun also met and befriended Mariano Ponce, then a diplomat of the First Philippine Republic.[46] During the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War, Sun helped Ponce procure weapons salvaged from the Imperial Japanese Army and ship the weapons to the Philippines. By helping the Philippine Republic, Sun hoped that the Filipinos would win their independence so that he could use the archipelago as a staging point of another revolution. However, as the war ended in July 1902, America emerged victorious from a bitter 3-year war against the Republic. Therefore, the Filipino dream of independence vanished with Sun's hopes of collaborating with the Philippines in his revolution in China.[47]

Huizhou uprising in China

On 22 October 1900, Sun launched the Huizhou uprising to attack Huizhou and provincial authorities in Guangdong.[48] This came five years after the failed Guangzhou uprising. This time, Sun appealed to the triads for help.[49] This uprising was also a failure. Miyazaki, who participated in the revolt with Sun, wrote an account of this revolutionary effort under the title "33-year dream" (三十三年之夢) in 1902.[50][51]

Further exile

Sun was in exile not only in Japan but also in Europe, the United States, and Canada. He raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, in 1896 Sun Yat-sen was detained at the Chinese Legation in London, where the Chinese Imperial secret service planned to smuggle him back to China to execute him for his revolutionary actions.[52] He was released after 12 days through the efforts of James Cantlie, The Globe, The Times, and the Foreign Office; leaving Sun a hero in Britain.[note 2] James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and would later write an early biography of Sun.[54]

Heaven and Earth Society, overseas travel

A "Heaven and Earth Society" sect known as Tiandihui had been around for a long time.[55] The group has also been referred to as the "three cooperating organizations" as well as the triads.[55] Sun Yat-sen mainly used this group to leverage his overseas travels to gain further financial and resource support for his revolution.[55] According to the New York Times "Sun Yat-sen left his village in Guangdong, southern China, in 1879 to join a brother in Hawaii. He eventually returned to China and from there moved to the British colony of Hong Kong in 1883. It was there that he received his Western education, his Christian faith and the money for revolution."[56] This is where Sun Yat-sen realized that China needed to change its ways. He knew that the only way that China would change and modernize would be to overthrow the Qing Dynasty.

According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed a certificate to enter the United States at a time when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 would have otherwise blocked him.[57] However, on Sun's first attempt to enter the US, he was still arrested.[57] He was later bailed out after 17 days.[57] In March 1904, while residing in Kula, Maui, Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth, issued by the Territory of Hawaii, stating that "he was born in the Hawaiian Islands on the 24th day of November, A.D. 1870."[58][59] He renounced it after it served its purpose to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.[59] Official files of the United States show that Sun had United States nationality, moved to China with his family at age 4, and returned to Hawaii 10 years later.[60]

Revolution

Tongmenghui

In 1904, Sun Yat-sen came about with the goal "to expel the Tatar barbarians (i.e. Manchu), to revive Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people" (驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權).[61] One of Sun's major legacies was the creation of his political philosophy of the Three Principles of the People. These Principles included the principle of nationalism (minzu, 民族), of democracy (minquan, 民權), and of welfare (minsheng, 民生).[61]

On 20 August 1905, Sun joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Tokyo, Japan to form the unified group Tongmenghui (United League), which sponsored uprisings in China.[61][62] By 1906 the number of Tongmenghui members reached 963 people.[61]

Malaya support

Sun's notability and popularity extends beyond the Greater China region, particularly to Nanyang (Southeast Asia), where a large concentration of overseas Chinese resided in Malaya (Malaysia and Singapore). While in Singapore, he met local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock (張永福), Tan Chor Nam (陳楚楠) and Lim Nee Soon (林義順), which mark the commencement of direct support from the Nanyang Chinese. The Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui was established on 6 April 1906,[64] though some records claim the founding date to be end of 1905.[64] The villa used by Sun was known as Wan Qing Yuan.[64][65] At this point Singapore was the headquarters of the Tongmenghui.[64]

Thus, after founding the Tong Meng Hui, Dr Sun advocated the establishment of The Chong Shing Yit Pao as the alliance's mouthpiece to promote revolutionary ideas. Later, he initiated the establishment of reading clubs across Singapore and Malaysia, in order to disseminate revolutionary ideas among the lower class through public readings of newspaper stories. The United Chinese Library, founded on 8 August 1910, was one such reading club, first set up at leased property on the second floor of the Wan He Salt Traders in North Boat Quay.[66]

The first actual United Chinese Library building was built between 1908 and 1911 below Fort Canning – 51 Armenian Street, commenced operations in 1912. The library was set up as a part of the 50 reading rooms by the Chinese Republicans to serve as an information station and liaison point for the revolutionaries. In 1987, the library was moved to its present site at Cantonment Road. But the Armenian Street building is still intact with the plaque at its entrance with Sun Yat Sen's words. With an initial membership of over 400, the library has about 180 members today. Although the United Chinese Library, with 102 years of history, was not the only reading club in Singapore during the time, today it is the only one of its kind remaining.

Siamese support

In 1903, Sun made a secret trip to Bangkok in which he sought funds for his cause in Southeast Asia. His loyal followers published newspapers, providing invaluable support to the dissemination of his revolutionary principles and ideals among Chinese descent in Thailand. In Bangkok, Sun visited Yaowarat Road, in Bangkok's Chinatown. It was on this street that Sun gave a speech claiming that overseas Chinese were "the Mother of the Revolution". He also met local Chinese merchants Seow Houtseng,[67] whose sent financial support to him.

Sun's speech on Yaowarat street was commemorated by the street later being named "Sun Yat Sen Street" or "Soi Sun Yat Sen" (Thai: ซอยซุนยัตเซ็น) in his honour.[68]

Zhennanguan uprising

On 1 December 1907, Sun led the Zhennanguan uprising against the Qing at Friendship Pass, which is the border between Guangxi and Vietnam.[69] The uprising failed after seven days of fighting.[69][70] In 1907 there were a total of four uprisings that failed including Huanggang uprising, Huizhou seven women lake uprising and Qinzhou uprising.[64] In 1908 two more uprisings failed one after another including Qin-lian uprising and Hekou uprising.[64]

Anti-Sun movements

Because of these failures, Sun's leadership was challenged by elements from within the Tongmenghui who wished to remove him as leader. In Tokyo 1907–1908 members from the recently merged Restoration society raised doubts about Sun's credentials.[64] Tao Chengzhang (陶成章) and Zhang Binglin publicly denounced Sun with an open leaflet called "A declaration of Sun Yat-sen's criminal acts by the revolutionaries in Southeast Asia".[64] This was printed and distributed in reformist newspapers like Nanyang Zonghui Bao.[64][71] Their goal was to target Sun as a leader leading a revolt for profiteering gains.[64]

The revolutionaries were polarized and split between pro-Sun and anti-Sun camps.[64] Sun publicly fought off comments about how he had something to gain financially from the revolution.[64] However, by 19 July 1910, the Tongmenghui headquarters had to relocate from Singapore to Penang to reduce the anti-Sun activities.[64] It is also in Penang that Sun and his supporters would launch the first Chinese "daily" newspaper, the Kwong Wah Yit Poh in December 1910.[69]

1911 revolution

To sponsor more uprisings, Sun made a personal plea for financial aid at the Penang conference held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya.[72] The leaders launched a major drive for donations across the Malay Peninsula.[72] They raised HK$187,000.[72]

On 27 April 1911, revolutionary Huang Xing led a second Guangzhou uprising known as the Yellow Flower Mound revolt against the Qing. The revolt failed and ended in disaster; the bodies of only 72 revolutionaries were found.[73] The revolutionaries are remembered as martyrs.[73]

On 10 October 1911, a military uprising at Wuchang took place led again by Huang Xing. At the time, Sun had no direct involvement as he was still in exile. Huang was in charge of the revolution that ended over 2000 years of imperial rule in China. When Sun learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, he returned to China from the United States accompanied by his closest foreign advisor, the American, "General" Homer Lea. He met Lea in London, where he and Lea unsuccessfully tried to arrange British financing for the new Chinese republic. Sun and Lea then sailed for China, arriving there on 21 December 1911.[74]

The uprising expanded to the Xinhai Revolution also known as the "Chinese Revolution" to overthrow the last Emperor Puyi. After this event, 10 October became known as the commemoration of Double Ten Day.[75]

Republic of China with multiple governments

Provisional government

On 29 December 1911 a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanking (Nanjing) elected Sun Yat-sen as the "provisional president" (臨時大總統).[76] 1 January 1912 was set as the first day of the First Year of the Republic.[77] Li Yuanhong was made provisional vice-president and Huang Xing became the minister of the army. The new Provisional Government of the Republic of China was created along with the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China. Sun is credited for the funding of the revolutions and for keeping the spirit of revolution alive, even after a series of failed uprisings. His successful merger of minor revolutionary groups to a single larger party provided a better base for all those who shared the same ideals. A number of things were introduced such as the republic calendar system and new fashion like Zhongshan suits.

Beiyang government

Yuan Shikai, who controlled the Beiyang Army, the military of northern China, was promised the position of President of the Republic of China if he could get the Qing court to abdicate.[78] On 12 February 1912 Emperor Puyi did abdicate the throne.[77] Sun stepped down as President, and Yuan became the new provisional president in Beijing on 10 March 1912.[78] The provisional government did not have any military forces of its own. Its control over elements of the New Army that had mutinied was limited and there were still significant forces which still had not declared against the Qing.

Sun Yat-sen sent telegrams to the leaders of all provinces requesting them to elect and to establish the National Assembly of the Republic of China in 1912.[79] In May 1912 the legislative assembly moved from Nanjing to Beijing with its 120 members divided between members of Tongmenghui and a Republican party that supported Yuan Shikai.[80] Many revolutionary members were already alarmed by Yuan's ambitions and the northern based Beiyang government.

Nationalist party and Second Revolution

Tongmenghui member Song Jiaoren quickly tried to control the parliament. He mobilized the old Tongmenghui at the core with the merger of a number of new small parties to form a new political party called the Kuomintang (Chinese nationalist party, commonly abbreviated as "KMT") on 25 August 1912 at Huguang Guild Hall Beijing.[80] The 1912–1913 National assembly election was considered a huge success for the KMT winning 269 of the 596 seats in the lower house and 123 of the 274 senate seats.[78][80] In retaliation the national party leader Song Jiaoren was assassinated, almost certainly by a secret order of Yuan, on 20 March 1913.[78] The Second Revolution took place where Sun and KMT military forces tried to overthrow Yuan's forces of about 80,000 men in an armed conflict in July 1913.[81] The revolt against Yuan was unsuccessful. In August 1913, Sun Yat-sen fled to Japan, where he later enlisted financial aid via politician and industrialist Fusanosuke Kuhara.[82]

Political chaos

In 1915 Yuan Shikai proclaimed the Empire of China (1915–1916) with himself as Emperor of China. Sun took part in the Anti-Monarchy war of the Constitutional Protection Movement, while also supporting bandit leaders like Bai Lang during the Bai Lang Rebellion. This marked the beginning of the Warlord Era. In 1915 Sun wrote to the Second International, a socialist-based organization in Paris, asking it to send a team of specialists to help China set up the world's first socialist republic.[83] At the time there were many theories and proposals of what China could be. In the political mess, both Sun Yat-sen and Xu Shichang were announced as President of the Republic of China.[84]

Path to Northern Expedition

Guangzhou militarist government

China had become divided among regional military leaders. Sun saw the danger of this and returned to China in 1917 to advocate Chinese reunification. In 1921 he started a self-proclaimed military government in Guangzhou and was elected Grand Marshal.[85] Between 1912 and 1927 three governments had been set up in South China: the Provisional government in Nanjing (1912), the Military government in Guangzhou (1921–1925), and the National government in Guangzhou and later Wuhan (1925–1927).[86] The government in the South was established to rival the Beiyang government in the north.[85] Yuan Shikai had banned the KMT. The short lived Chinese Revolutionary Party was a temporary replacement for the KMT. On 10 October 1919 Sun resurrected the KMT with the new name Chung-kuo Kuomintang, or the "Nationalist Party of China".[80]

KMT–CPC cooperation

By this time Sun had become convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of political tutelage that would culminate in the transition to democracy. In order to hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active cooperation with the Communist Party of China (CPC). Sun and the Soviet Union's Adolph Joffe signed the Sun-Joffe Manifesto in January 1923.[3] Sun received help from the Comintern for his acceptance of communist members into his KMT. Revolutionary and socialist leader Vladimir Lenin praised Sun and the KMT for their ideology and principles. Lenin praised Sun and his attempts at social reformation, and also congratulated him for fighting foreign Imperialism.[87][88][89] Sun also returned the praise, calling him a "great man", and sent his congratulations on the revolution in Russia.[90]

With the Soviets' help, Sun was able to develop the military power needed for the Northern Expedition against the military at the north. He established the Whampoa Military Academy near Guangzhou with Chiang Kai-shek as the commandant of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA).[91] Other Whampoa leaders include Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin as political instructors. This full collaboration was called the First United Front.

Finance concerns

In 1924 Sun appointed his brother-in-law T. V. Soong to set up the first Chinese Central bank called the Canton Central Bank.[92] To establish national capitalism and a banking system was a major objective for the KMT.[93] However Sun was not without some opposition as there was the Canton volunteers corps uprising against him.

Final speeches

In February 1923 Sun made a presentation to the Students' Union in Hong Kong University and declared that it was the corruption of China and the peace, order and good government of Hong Kong that turned him into a revolutionary.[94][95] This same year, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed his Three Principles of the People as the foundation of the country and the Five-Yuan Constitution as the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into the National Anthem of the Republic of China.

On 10 November 1924, Sun traveled north to Tianjin and delivered a speech to suggest a gathering for a "national conference" for the Chinese people. It called for the end of warlord rules and the abolition of all unequal treaties with the Western powers.[96] Two days later, he traveled to Beijing to discuss the future of the country, despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the warlords. Among the people he met was the Muslim General Ma Fuxiang, who informed Sun that they would welcome his leadership.[97] On 28 November 1924 Sun traveled to Japan and gave a speech on Pan-Asianism at Kobe, Japan.[98]

Illness and death

For many years, it was popularly believed that Sun died of liver cancer. On 26 January 1925, Sun underwent an exploratory laparotomy at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) to investigate a long-term illness. This was performed by the head of the Department of Surgery, Adrian S. Taylor, who stated that the procedure "revealed extensive involvement of the liver by carcinoma" and that Sun only had about ten days to live. Sun was hospitalized and his condition was treated with radium.[99] Sun survived the initial ten-day period and on 18 February, against the advice of doctors, he was transferred to the KMT headquarters and treated with traditional Chinese medicine. This too was unsuccessful and he died on 12 March at the age of 58.[100] Contemporary reports in The New York Times,[100] Time,[101] and the Chinese newspaper Qun Qiang Bao all reported the cause of death as liver cancer, based on Taylor's observation.[102]

Following this the body then was preserved in mineral oil[103] and taken to the Temple of Azure Clouds, a Buddhist shrine in the Western Hills a few miles outside of Beijing.[104] He also left a short political will (總理遺囑) penned by Wang Jingwei, which had a widespread influence in the subsequent development of the Republic of China and Taiwan.[105]

In 1926, construction began on a majestic mausoleum at the foot of Purple Mountain in Nanjing, and this was completed in the spring of 1929. On 1 June 1929, Sun's remains were moved from Beijing and interred in the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum.

By pure chance, in May 2016, an American pathologist named Rolf F. Barth was visiting the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Guangzhou when he noticed a faded copy of the original autopsy report on display. The autopsy was performed immediately after Sun's death by James Cash, a pathologist at PUMCH. Based on a tissue sample, Cash concluded that the cause of death was an adenocarcinoma in the gallbladder that had metastasized to the liver. In modern China, liver cancer is far more common than gallbladder cancer and although the incidence rates of either in 1925 are not known, if one assumes that they were similar at that time, then the original diagnosis by Taylor was a logical conclusion. From the time of Sun's death until the appearance of Barth's report[99] in the Chinese Journal of Cancer in September 2016 (now known as Cancer Communications[106] since 1 March 2018), the true cause of death of Sun Yat-sen was not reported in any English-language publication. Even in Chinese-language sources, it only appeared in one non-medical online report in 2013.[99][107]

Legacy

Power struggle

After Sun's death, a power struggle between his young protégé Chiang Kai-shek and his old revolutionary comrade Wang Jingwei split the KMT. At stake in this struggle was the right to lay claim to Sun's ambiguous legacy. In 1927 Chiang Kai-shek married Soong Mei-ling, a sister of Sun's widow Soong Ching-ling, and subsequently he could claim to be a brother-in-law of Sun. When the Communists and the Kuomintang split in 1927, marking the start of the Chinese Civil War, each group claimed to be his true heirs, a conflict that continued through World War II. Sun's widow, Soong Ching-ling, sided with the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and served from 1949 to 1981 as Vice-President (or Vice-Chairwoman) of the People's Republic of China and as Honorary President shortly before her death in 1981.

Cult of personality

A personality cult in the Republic of China was centered on Sun and his successor, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Chinese Muslim Generals and Imams participated in this cult of personality and one party state, with Muslim General Ma Bufang making people bow to Sun's portrait and listen to the national anthem during a Tibetan and Mongol religious ceremony for the Qinghai Lake God.[108] Quotes from the Quran and Hadith were used among Hui Muslims to justify Chiang Kai-shek's rule over China.[109]

The Kuomintang's constitution designated Sun as party president. After his death, the Kuomintang opted to keep that language in its constitution to honor his memory forever. The party has since been headed by a director-general (1927–1975) and a chairman (since 1975), which discharge the functions of the president.

Father of the Nation

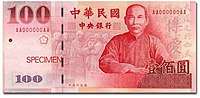

Sun Yat-sen remains unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for having a high reputation both in mainland China and in Taiwan. In Taiwan, he is seen as the Father of the Republic of China, and is known by the posthumous name Father of the Nation, Mr. Sun Zhongshan (Chinese: 國父 孫中山先生, where the one-character space is a traditional homage symbol).[8] His likeness is still almost always found in ceremonial locations such as in front of legislatures and classrooms of public schools, from elementary to senior high school, and he continues to appear in new coinage and currency.

"Forerunner of the revolution"

On the mainland, Sun is seen as a Chinese nationalist, proto-socialist, first president of a Republican China and is highly regarded as the Forerunner of the Revolution (革命先行者).[3] He is even mentioned by name in the preamble to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China. In recent years, the leadership of the Communist Party of China has increasingly invoked Sun, partly as a way of bolstering Chinese nationalism in light of Chinese economic reform and partly to increase connections with supporters of the Kuomintang on Taiwan which the PRC sees as allies against Taiwan independence. Sun's tomb was one of the first stops made by the leaders of both the Kuomintang and the People First Party on their pan-blue visit to mainland China in 2005.[110] A massive portrait of Sun continues to appear in Tiananmen Square for May Day and National Day.

Economic development

Sun Yat-sen spent years in Hawaii as a student in the late 1870s and early 1880s, and was highly impressed with the economic development he saw there. He used the independent Kingdom of Hawaii as a model to develop his vision of a technologically modern and politically independent and actively anti-imperialist China.[111] Sun Yat-sen was an important pioneer of international development, proposing in the 1920s international institutions of the sort that appeared after World War II. He focused on China, with its vast potential and weak base of mostly local entrepreneurs.[112] His key proposal was socialism. He proposed:

- The State will take over all the large enterprises; we shall encourage and protect enterprises which may reasonably be entrusted to the people; the nation will possess equality with other nations; every Chinese will be equal to every other Chinese both politically and in his opportunities of economic advancement. [113]

Family

Sun Yat-sen was born to Sun Dacheng (孫達成) and his wife, lady Yang (楊氏) on 12 November 1866.[114] At the time his father was age 53, while his mother was 38 years old. He had an older brother, Sun Dezhang (孫德彰), and an older sister, Sun Jinxing (孫金星), who died at the early age of 4. Another older brother, Sun Deyou (孫德祐), died at the age of 6. He also had an older sister, Sun Miaoqian (孫妙茜), and a younger sister, Sun Qiuqi (孫秋綺).[24]

At age 20, Sun had an arranged marriage with fellow villager Lu Muzhen. She bore a son, Sun Fo, and two daughters, Sun Jinyuan (孫金媛) and Sun Jinwan (孫金婉).[24] Sun Fo was the grandfather of Leland Sun, who spent 37 years working in Hollywood as an actor and stuntman.[115] Sun Yat-sen was also the godfather of Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, American author and poet who wrote under the name Cordwainer Smith.[116]

Sun's first concubine, the Hong Kong-born Chen Cuifen, lived in Taiping, Perak, Malaysia for 17 years. The couple adopted a local girl as their daughter. Cuifen subsequently relocated to China, where she died.[117]

On 25 October 1915 in Japan, Sun married Soong Ching-ling, one of the Soong sisters,[24][118] Soong Ching-Ling's father was the American-educated Methodist minister Charles Soong, who made a fortune in banking and in printing of Bibles. Although Charles Soong had been a personal friend of Sun's, he was enraged when Sun announced his intention to marry Ching-ling because while Sun was a Christian he kept two wives, Lu Muzhen and Kaoru Otsuki; Soong viewed Sun's actions as running directly against their shared religion.

Soong Ching-Ling's sister, Soong Mei-ling, later married Chiang Kai-shek.

Cultural references

Memorials and structures in Asia

In most major Chinese cities one of the main streets is named Zhongshan Lu (中山路) to celebrate his memory. There are also numerous parks, schools, and geographical features named after him. Xiangshan, Sun's hometown in Guangdong, was renamed Zhongshan in his honor, and there is a hall dedicated to his memory at the Temple of Azure Clouds in Beijing. There are also a series of Sun Yat-sen stamps.

Other references to Sun include the Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou and National Sun Yat-sen University in Kaohsiung. Other structures include Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall subway station, Sun Yat-sen house in Nanjing, Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum in Hong Kong, Chung-Shan Building, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Guangzhou, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Taipei and Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall in Singapore. Zhongshan Memorial Middle School has also been a name used by many schools. Zhongshan Park is also a common name used for a number of places named after him. The first highway in Taiwan is called the Sun Yat-sen expressway. Two ships are also named after him, the Chinese gunboat Chung Shan and Chinese cruiser Yat Sen. The old Chinatown in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata), India has a prominent street by the name of Sun Yat-sen street. There are also two streets named after Sun Yat-sen, located in the cities of Astrakhan and Ufa, Russia.

In George Town, Penang, Malaysia, the Penang Philomatic Union had its premises at 120 Armenian Street in 1910, during the time when Sun spent more than four months in Penang, convened the historic "Penang Conference" to launch the fundraising campaign for the Huanghuagang Uprising and founded the Kwong Wah Yit Poh; this house, which has been preserved as the Sun Yat-sen Museum (formerly called the Sun Yat Sen Penang Base), was visited by President designate Hu Jintao in 2002. The Penang Philomatic Union subsequently moved to a bungalow at 65 Macalister Road which has been preserved as the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Centre Penang.

As dedication, the 1966 Chinese Cultural Renaissance was launched on Sun's birthday on 12 November.[119]

The Nanyang Wan Qing Yuan in Singapore have since been preserved and renamed as the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.[65] A Sun Yat-sen heritage trail was also launched on 20 November 2010 in Penang.[120]

Sun's US citizen Hawaii birth certificate that show he was not born in the ROC, but instead born in the US was on public display at the American Institute in Taiwan on US Independence day 4 July 2011.[121]

A street in Medan, Indonesia is named "Jalan Sun Yat-Sen" in honour of him.[122]

A street named "Tôn Dật Tiên" (Sino-Vietnamese name for Sun Yat-Sen) is located in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Gallery

Mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen, Nanjing.

Mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen, Nanjing. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, Guangzhou.

Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, Guangzhou. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, Taipei

Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, Taipei- Sun Yat-sen Memorial Centre, George Town, Penang, Malaysia

- A marker on the Sun Yat-sen Historical Trail on Hong Kong Island

Dr Sun Yat-sen on the NT$100 banknote of Taiwan

Dr Sun Yat-sen on the NT$100 banknote of Taiwan

Memorials and structures outside of Asia

St. John's University in New York City has a facility built in 1973, the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall, built to resemble a traditional Chinese building in honor of Sun.[123] Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden is located in Vancouver, the largest classical Chinese gardens outside of Asia. There is the Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park in Chinatown, Honolulu.[124] On the island of Maui, there is the little Sun Yat-sen Park at Kamaole. It is located near to where his older brother had a ranch on the slopes of Haleakala in the Kula region.[15][16][17][44]

In Chinatown, Los Angeles, there is a seated statue of him in Central Plaza.[125] In Sacramento, California there is a bronze statue of Sun in front of the Chinese Benevolent Association of Sacramento. Another statue of Sun Yat-sen by Joe Rosenthal can be found at Riverdale Park in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. There is also the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University. In Chinatown, San Francisco, there is a 12-foot statue of him on Saint Mary's Square.[126]

In late 2011, the Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of China, unveiled, in a Lion Dance Blessing ceremony, a memorial statue of Sun outside the Chinese Museum in Melbourne's Chinatown, on the spot where their traditional Chinese New Year Lion Dance always ends.[127]

In 1993 Lily Sun, one of Sun Yat-sen's granddaughters, donated books, photographs, artwork and other memorabilia to the Kapi'olani Community College library as part of the "Sun Yat-sen Asian collection".[128] During October and November every year the entire collection is shown.[128] In 1997 the "Dr Sun Yat-sen Hawaii foundation" was formed online as a virtual library.[128] In 2006 the NASA Mars Exploration Rover Spirit labeled one of the hills explored "Zhongshan".[129]

The plaque shown earlier in this article is by Dora Gordine, and is situated on the site of Sun's lodgings in London in 1896, 8 Grays Inn Place. There is also a blue plaque commemorating Sun at The Kennels, Cottered, Hertfordshire, the country home of the Cantlies where Sun came to recuperate after his rescue from the legation in 1896.

A street named Sun Yat-Sen Avenue is located in Markham, Ontario. This is the first such street name outside of Asia.

In popular culture

Opera

Dr. Sun Yat-sen[130] (中山逸仙; ZhōngShān yì xiān) is a 2011 Chinese-language western-style opera in three acts by the New York-based American composer Huang Ruo who was born in China and is a graduate of Oberlin College's Conservatory as well as the Juilliard School. The libretto was written by Candace Mui-ngam Chong, a recent collaborator with playwright David Henry Hwang.[131] It was performed in Hong Kong in October 2011 and was given its North American premiere on 26 July 2014 at The Santa Fe Opera.

TV series and films

The life of Sun is portrayed in various films, mainly The Soong Sisters and Road to Dawn. A fictionalized assassination attempt on his life was featured in Bodyguards and Assassins. He is also portrayed during his struggle to overthrow the Qing dynasty in Once Upon a Time in China II. The TV series Towards the Republic features Ma Shaohua as Sun Yat-sen. In the 100th anniversary tribute of the film 1911, Winston Chao played Sun.[132] In Space: Above and Beyond, one of the starships of the China Navy is named the Sun Yat-sen.[133]

Controversy

New Three Principles of the People

At one time CPC general secretary and PRC president Jiang Zemin claimed that Sun Yat-sen advocated a movement known as the "New Three Principles of the People" (新三民主義) which consisted of "working with the soviets, working with the communists and helping the farmers" (聯俄, 聯共, 扶助工農).[136][137] In 2001 Lily Sun said that the CPC was distorting Sun's legacy. She then voiced her displeasure in 2002 in a private letter to Jiang about the distortion of history.[136] In 2008 Jiang Zemin was willing to offer US$10 million to sponsor a Xinhai Revolution anniversary celebration event. According to Ming Pao she could not take the money because she would no longer have the freedom to communicate about the revolution.[136] This concept is still currently available on Baike Baidu.

KMT emblem removal case

In 1981, Lily Sun took a trip to Sun Yat-sen mausoleum in Nanjing, People's Republic of China. The emblem of the KMT had been removed from the top of his sacrificial hall at the time of her visit, but was later restored. On another visit in May 2011, she was surprised to find the four characters "General Rules of Meetings" (會議通則), a document that Sun wrote in reference to Robert's Rules of Order had been removed from a stone carving.[136]

Father of Independent Taiwan issue

In November 2004, the ROC Ministry of Education proposed that Sun Yat-sen was not the father of Taiwan. Instead, Sun was a foreigner from mainland China.[138] Taiwanese Education minister Tu Cheng-sheng and Examination Yuan member Lin Yu-ti, both of whom supported the proposal, had their portraits pelted with eggs in protest.[139] At a Sun Yat-sen statue in Kaohsiung, a 70-year-old ROC retired soldier committed suicide as a way to protest the ministry proposal on the anniversary of Sun's birthday 12 November.[138][139]

Works

- The Outline of National Reconstruction/Chien Kuo Ta Kang (1918)

- The Fundamentals of National Reconstruction/Jianguo fanglue (1924)

- The Principle of Nationalism (1953)

See also

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Chinese Anarchism

- History of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Sun Yat-sen Museum Penang

- United States Constitution and worldwide influence

- Zhongshan suit

Notes

- This is a Chinese name; the family name is Sun.

- Contrary to popular legends, Sun entered the Legation voluntarily, but was prevented from leaving. The Legation planned to execute him, before returning his body to Beijing for ritual beheading. Cantlie, his former teacher, was refused a writ of habeas corpus because of the Legation's diplomatic immunity, but he began a campaign through The Times. The Foreign Office persuaded the Legation to release Sun through diplomatic channels.[53]

References

- Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. 特別策劃 section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition 民國之父.

- "Chronology of Dr. Sun Yat-sen". National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Tung, William L. [1968] (1968). The political institutions of modern China. Springer publishing. ISBN 9789024705528. p 92. P106.

- Barth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (2 September 2016). "What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 81. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9. PMC 5009495. PMID 27586157.

- "Three Principles of the People". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Schoppa, Keith R. [2000] (2000). The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia university press. ISBN 0231500378, ISBN 9780231500371. p 73, 165, 186.

- Sun Yat-sen (3 August 1924). "三民主義:民生主義 第一講 [Three Principles of the People : People's living]". 國父全集 [Father of the nation's scripts]. 中山學術資料庫系統 (in Chinese). p. 0129–0145. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

我們國民黨提倡民生主義,已經有了二十多年,不講社會主義,祇講民生主義。社會主義和民生主義的範圍是甚麼關係呢?近來美國有一位馬克思的信徒威廉氏,深究馬克思的主義,見得自己同門互相紛爭,一定是馬克思學說還有不充分的地方,所以他便發表意見,說馬克思以物質為歷史的重心是不對的,社會問題才是歷史的重心;而社會問題中又以生存為重心,那才是合理。民生問題就是生存問題......

- Wang, Ermin (王爾敏) (April 2011). 思想創造時代:孫中山與中華民國. Showwe Information Co., Ltd. p. 274. ISBN 978-986-221-707-8.

- Wang, Shounan (王壽南) (2007). Sun Zhong-san. Commercial Press Taiwan. p. 23. ISBN 978-957-05-2156-6.

- 游梓翔 (2006). 領袖的聲音: 兩岸領導人政治語藝批評, 1906–2006. Wu-Nan Book Inc. p. 82. ISBN 978-957-11-4268-5.

- 门杰丹 (4 December 2003). 浓浓乡情系中原—访孙中山先生孙女孙穗芳博士 [Central Plains Nostalgia-Interview with Dr. Sun Suifang, granddaughter of Sun Yat-sen]. China News (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Translate this Chinese article to English

- Bohr, P. Richard (2009). "Did the Hakka Save China? Ethnicity, Identity, and Minority Status in China's Modern Transformation". Headwaters. 26 (3): 16.

- Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. 1998. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8047-4011-1.

- Kubota, Gary (20 August 2017). "Students from China study Sun Yat-sen on Maui". Star-Advertiser. Honolulu. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- KHON web staff (3 June 2013). "Chinese government officials attend Sun Mei statue unveiling on Maui". KHON2. Honolulu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park". Hawaii Guide. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Sun Yet Sen Park". County of Maui. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (class of 1882)". ʻIolani School website. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- Brannon, John (16 August 2007). "Chinatown park, statue honor Sun Yat-sen". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

Sun graduated from Iolani School in 1882, then attended Oahu College—now known as Punahou School—for one semester.

- 基督教與近代中國革命起源:以孫中山為例. Big5.chinanews.com:89. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- 歷史與空間:基督教與近代中國革命的起源──以孫中山為例 – 香港文匯報. Paper.wenweipo.com. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- 中山史蹟徑一日遊. Lcsd.gov.hk. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- HK university. [2002] (2002). Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years. ISBN 962-209-613-1, ISBN 978-962-209-613-4.

- Singtao daily. 28 February 2011. 特別策劃 section A10. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition.

- South China morning post. Birth of Sun heralds dawn of revolutionary era for China. 11 November 1999.

- , Sun Yat-sen and Christianity.

- "...At present there are some seven members in the interior belonging to our mission, and two here, one I baptized last Sabbath,a young man who is attending the Government Central School. We had a very pleasant communion service yesterday..." – Hager to Clark, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.17, p.3

- "...We had a pleasant communion yesterday and received one Chinaman into the church..." – Hager to Pond, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.18, p.3 postscript

- Rev. C. R. Hager, 'The First Citizen of the Chinese Republic', The Medical Missionary v.22 1913, p.184

- Bergère: 26

- Soong, (1997) p. 151-178

- 中西區區議會 [Central & Western District Council] (November 2006), 孫中山先生史蹟徑 [Dr Sun Yat-sen Historical Trail] (PDF), Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum (in Chinese and English), Hong Kong, China: Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum, p. 30, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012, retrieved 15 September 2012

- Bard, Solomon. Voices from the past: Hong Kong, 1842–1918. [2002] (2002). HK university press. ISBN 962-209-574-7, ISBN 978-962-209-574-8. p. 183.

- Curthoys, Ann. Lake, Marilyn. [2005] (2005). Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective. ANU publishing. ISBN 1-920942-44-0, ISBN 978-1-920942-44-1. pg 101.

- Wei, Julie Lee. Myers Ramon Hawley. Gillin, Donald G. [1994] (1994). Prescriptions for saving China: selected writings of Sun Yat-sen. Hoover press. ISBN 0-8179-9281-2, ISBN 978-0-8179-9281-1.

- 王恆偉 (2006). #5 清 [Chapter 5. Qing dynasty]. 中國歷史講堂. 中華書局. p. 146. ISBN 962-8885-28-6.

- Bergère: 39–40

- Bergère: 40–41

- (Chinese) Yang, Bayun; Yang, Xing'an (November 2010). Yeung Ku-wan – A Biography Written by a Family Member. Bookoola. p. 17. ISBN 978-988-18-0416-7

- Faure, David (1997). Society. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622093935., founder Tse Tsan-tai's account

- 孫中山第一次辭讓總統並非給袁世凱 – 文匯資訊. Info.wenweipo.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Bevir, Mark. [2010] (2010). Encyclopedia of Political Theory. Sage publishing. ISBN 1-4129-5865-2, ISBN 978-1-4129-5865-3. pg 168.

- Lin, Xiaoqing Diana. [2006] (2006). Peking University: Chinese Scholarship And Intellectuals, 1898–1937. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6322-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-6322-2. pg 27.

- Paul Wood (November–December 2011). "The Other Maui Sun". Wailuku, Hawaii: Maui Nō Ka ʻOi Magazine. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "JapanFocus". Old.japanfocus.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Thornber, Karen Laura. [2009] (2009). Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature. Harvard university press. pg 404.

- Ocampo, Ambeth (2010). Looking Back 2. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing. pp. 8–11.

- Gao, James Zheng. [2009] (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Scarecrow press. ISBN 0-8108-4930-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-4930-3. Chronology section.

- Bergère: 86

- 劉崇稜 (2004). 日本近代文學精讀. p. 71. ISBN 978-957-11-3675-2.

- Frédéric, Louis. [2005] (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01753-6, ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. pg 651.

- "Sun Yat-sen | Chinese leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Wong, J.Y. (1986). The Origins of a Heroic Image: SunYat Sen in London, 1896–1987. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

as summarized in

Clark, David J.; Gerald McCoy (2000). The Most Fundamental Legal Right: Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780198265849. - Cantlie, James (1913). Sun Yat Sen and the Awakening of China. London: Jarrold & Sons.

- João de Pina-Cabral. [2002] (2002). Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao. Berg publishing. ISBN 0-8264-5749-5, ISBN 978-0-8264-5749-3. pg 209.

- England, Vaudine (17 September 2007). "Hong Kong rediscovers Sun Yat-sen". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- 孫中山思想 3學者演說精采. World journal. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Sun Yat-sen: Certification of Live Birth in Hawaii". San Francisco, CA, USA: Scribd. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Smyser, A.A. (2000). Sun Yat-sen's strong links to Hawaii. Honolulu Star Bulletin. "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898."

- Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service. San Francisco District Office. "Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925" (PDF). Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004 ]. Washington, DC, USA: National Archives and Records Administration. pp. 92–152. Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925 at the National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012. Note that one immigration official recorded that Sun Yat-sen was born in Kula, a district of Maui, Hawaii.

- 計秋楓, 朱慶葆. [2001] (2001). 中國近代史, Volume 1. Chinese university press. ISBN 962-201-987-0, ISBN 978-962-201-987-4. pg 468.

- "Internal Threats – The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) – Imperial China – History – China – Asia". Countriesquest.com. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Streets of George Town, Penang. Areca Books. 2007. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-983-9886-00-9.

- Yan, Qinghuang. [2008] (2008). The Chinese in Southeast Asia and beyond: socioeconomic and political dimensions. World Scientific publishing. ISBN 981-279-047-0, ISBN 978-981-279-047-7. pg 182–187.

- "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall". Wanqingyuan.org.sg. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "United Chinese Library". Roots. National Heritage Board.

- Eiji Murashima. "The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand" (PDF). Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (Waseda University). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Eric Lim. "Soi Sun Yat Sen the legacy of a revolutionary". Tour Bangkok Legacies. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Khoo, Salma Nasution. [2008] (2008). Sun Yat Sen in Penang. Areca publishing. ISBN 983-42834-8-2, ISBN 978-983-42834-8-3.

- Tang Jiaxuan. [2011] (2011). Heavy Storm and Gentle Breeze: A Memoir of China's Diplomacy. HarperCollins publishing. ISBN 0-06-206725-7, ISBN 978-0-06-206725-8.

- Nanyang Zonghui bao. The Union Times paper. 11 November 1909 p2.

- Bergère: 188

- 王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. ISBN 962-8885-28-6. p 195-198.

- Bergère: 210

- Carol, Steven. [2009] (2009). Encyclopedia of Days: Start the Day with History. iUniverse publishing. ISBN 0-595-48236-8, ISBN 978-0-595-48236-8.

- Lane, Roger deWardt. [2008] (2008). Encyclopedia Small Silver Coins. ISBN 0-615-24479-3, ISBN 978-0-615-24479-2.

- Welland, Sasah Su-ling. [2007] (2007). A Thousand miles of dreams: The journeys of two Chinese sisters. Rowman littlefield publishing. ISBN 0-7425-5314-0, ISBN 978-0-7425-5314-9. pg 87.

- Fu, Zhengyuan. (1993). Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics(Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44228-1, ISBN 978-0-521-44228-2). pp. 153–154.

- Bergère: 226

- Ch'ien Tuan-sheng. The Government and Politics of China 1912–1949. Harvard University Press, 1950; rpr. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0551-8, ISBN 978-0-8047-0551-6. pp. 83–91.

- Ernest Young, "Politics in the Aftermath of Revolution," in John King Fairbank, ed., The Cambridge History of China: Republican China 1912–1949, Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1983; ISBN 0-521-23541-3, ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9), p. 228.

- Altman, Albert A., and Harold Z. Schiffrin. “Sun Yat-Sen and the Japanese: 1914–16.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 1972, pp. 385–400. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/311539

- South China morning post. Sun Yat-sen's durable and malleable legacy. 26 April 2011.

- South China morning post. 1913–1922. 9 November 2003.

- Bergère & Lloyd: 273

- Kirby, William C. [2000] (2000). State and economy in republican China: a handbook for scholars, volume 1. Harvard publishing. ISBN 0-674-00368-3, ISBN 978-0-674-00368-2. pg 59.

- Robert Payne (2008). Mao Tse-tung: Ruler of Red China. READ BOOKS. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4437-2521-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 1980. p. 237. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1982). Great Soviet encyclopedia, Volume 25. Macmillan. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Bernice A Verbyla (2010). Aunt Mae's China. Xulon Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-60957-456-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Gao. James Zheng. [2009] (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Scarecrow press. ISBN 0-8108-4930-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-4930-3. pg 251.

- Spence, Jonathan D. [1990] (1990). The search for modern China. WW Norton & company publishing. ISBN 0-393-30780-8, ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1. Pg 345.

- Ji, Zhaojin. [2003] (2003). A history of modern Shanghai banking: the rise and decline of China's finance capitalism. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 0-7656-1003-5, ISBN 978-0-7656-1003-4. pg 165.

- Ho, Virgil K.Y. [2005] (2005). Understanding Canton: Rethinking Popular Culture in the Republican Period. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928271-4

- Carroll, John Mark. Edge of Empires:Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01701-3

- Ma Yuxin [2010] (2010). Women journalists and feminism in China, 1898–1937. Cambria Press. ISBN 1-60497-660-8, ISBN 978-1-60497-660-1. p. 156.

- 马福祥,临夏回族自治州马福祥,马福祥介绍---走遍中国. www.elycn.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Calder, Kent; Ye, Min [2010] (2010). The Making of Northeast Asia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-6922-2, ISBN 978-0-8047-6922-8.

- Barth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (1 January 2016). "What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 81. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9. ISSN 1944-446X. PMC 5009495. PMID 27586157.

- "Dr. Sun Yat-sen Dies in Peking". The New York Times. 12 March 1925. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Lost Leader". Time. 23 March 1925. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

A year ago his death was prematurely announced; but it was not until last January that he was taken to the Rockefeller Hospital at Peking and declared to be in the advanced stages of cancer of the liver.

- Sharman, L. (1968) [1934]. Sun Yat-sen: His life and times. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 305–306, 310.

- Bullock, M.B. (2011). The oil prince's legacy: Rockefeller philanthropy in China. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8047-7688-2.

- Leinwand, Gerald (9 September 2002). 1927: High Tide of the 1920s. Basic Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-56858-245-0. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- 國父遺囑 [Founding Father's Will]. Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Cancer Communications". Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "Clinical record copies from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital decrypt the real cause of death of Sun Yat-sen". Nanfang Daily (in Chinese). 11 November 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 134; 375. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Rosecrance, Richard N. Stein, Arthur A. [2006] (2006). No more states?: globalization, national self-determination, and terrorism.Rowman & Littlefield publishing. ISBN 0-7425-3944-X, 9780742539440. pg 269.

- Lorenz Gonschor, "Revisiting the Hawaiian Influence on the Political Thought of Sun Yat-sen." Journal of Pacific History 52.1 (2017): 52–67.

- Eric Helleiner, "Sun Yat-sen as a Pioneer of International Development." History of Political Economy 50.S1 (2018): 76–93.

- Stephen Shen, and Robert Payne, Sun Yat-Sen: A Portrait (1946) p 182

- 孫中山學術研究資訊網 – 國父的家世與求學 [Dr. Sun Yat-sen's family background and schooling]. [sun.yatsen.gov.tw/ sun.yatsen.gov.tw (in Chinese). 16 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Sun Yat-sen's descendant wants to see unified China". News.xinhuanet.com. 11 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Tripping Cyborgs and Organ Farms: The Fictions of Cordwainer Smith | NeuroTribes". NeuroTribes. 21 September 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Antong Cafe, The Oldest Coffee Mill in Malaysia". Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Isaac F. Marcosson, Turbulent Years (1938), p.249

- Guy, Nancy. [2005] (2005). Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02973-9. pg 67.

- "Sun Yet Sen Penang Base – News 17". Sunyatsenpenang.com. 19 November 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Sun Yat-sen's US birth certificate to be shown". Taipei Times. 2 October 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Google Maps". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Queens Campus". www.youvisit.com. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen". The City and County of Honolulu. 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Sun Yat-sen". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "St. Mary's Square in San Francisco Chinatown – The largest chinatown outside of Asia". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne". www.cysm.org. Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Char Asian-Pacific Study Room". Library.kcc.hawaii.edu. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: Press Release Images: Spirit". Marsrover.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Opera Dr Sun Yat-sen to stage in Hong Kong". News.xinhuanet.com. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Gerard Raymond, "Between East and West: An Interview with David Henry Hwang" on slantmagazine.com, 28 October 2011

- "Commemoration of 1911 Revolution mounting in China". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Space: Above and Beyond s01e22 Episode Script SS". www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- 《斜路黃花》向革命者致意 (in Chinese). Takungpao.com. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- 元智大學管理學院 (in Chinese). Cm.yzu.edu.tw. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Kenneth Tan (3 October 2011). "Granddaughter of Sun Yat-Sen accuses China of distorting his legacy". Shanghaiist. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- 国父孙女轰中共扭曲三民主义愚民_多维新闻网 (in Chinese). China.dwnews.com. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- 人民网—孙中山遭辱骂 "台独"想搞"台湾国父". People's Daily. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Chiu Hei-yuan (5 October 2011). "History should be based on facts". Taipei Times. p. 8.

Further reading

- Bergère, Marie-Claire (2000). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4011-9. online free to borrow

- Pearl S. Buck, The Man Who Changed China: The Story of Sun Yat-sen (1953)

- D'Elia, Paschal M. Sun Yat-sen. His Life and Its Meaning, a Critical Biography (1936)

- Du, Yue. "Sun Yat-sen as Guofu: Competition over Nationalist Party Orthodoxy in the Second Sino-Japanese War." Modern China 45.2 (2019): 201–235.

- Kayloe, Tjio. The Unfinished Revolution: Sun Yat-Sen and the Struggle for Modern China (2017). excerpt

- Khoo, Salma Nasution. Sun Yat Sen in Penang (Areca Books, 2008).

- Lee, Lai To, and Hock Guan Lee, eds. (2011). Sun Yat-Sen, Nanyang and the 1911 Revolution. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814345460.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Linebarger, Paul M.A. Sun Yat Sen And The Chinese Republic (1925) online free

- Linebarger, Paul M.A. Political Doctrines Of Sun Yat-sen (1937) online free

- Martin, Bernard. Sun Yat-sen's vision for China (1966)

- Restarick, Henry B., Sun Yat-sen, Liberator of China. (Yale UP, 1931)

- Schiffrin, Harold Z. Sun Yat-sen: Reluctant Revolutionary (1980)

- Schiffrin, Harold Z. Sun Yat-sen and the origins of the Chinese revolution (1968).

- Shen, Stephen and Robert Payne. Sun Yat-Sen: A Portrait (1946) online free

- Soong, Irma Tam. "Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i." The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 31 (1997) online

- Wilbur, Clarence Martin. Sun Yat-sen, frustrated patriot (Columbia University Press, 1976), a major scholarly biography

- Yu, George T. "The 1911 Revolution: Past, Present, and Future," Asian Survey, 31#10 (1991), pp. 895–904, online historiography

External links

- "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang memorial hall". Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Doctor Sun Yat Sen memorial hall". Archived from the original on 29 August 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2005.

- ROC Government Biography (in English and Chinese)

- Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Contemporary views of Sun among overseas Chinese

- Yokohama Overseas Chinese School established by Dr. Sun Yat-sen

- National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall Official Website (in English and Chinese)

- Homer Lea Research Center

- Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Foundation of Hawaii A virtual library on Dr. Sun in Hawaii including sources for six visits

- Who is Homer Lea? Sun's best friend. He trained Chinese soldiers and prepared the frame work for the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

- Works by Sun Yat-sen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sun Yat-sen at Internet Archive

- Funeral procession for Sun Yat-sen in Chinatown, Los Angeles at the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Xuantong Emperor (Puyi) as Emperor of the Qing dynasty |

Head of state of China as Provisional President of the Republic of China 1912 |

Succeeded by Yuan Shih-kai as Provisional President of the Republic of China |

| Preceded by Office created |

Generalissimo of the Military Government of Nationalist China 1917–1918 |

Succeeded by Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

| Preceded by Himself as Generalissimo of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

Member of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China 1918 |

Succeeded by Cen Chunxuan as Chairman of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

| Preceded by Cen Chunxuan as Chairman of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

Member of the Governing Committee of the Military Government of Nationalist China 1920–1921 |

Succeeded by Himself as Extraordinary President of Nationalist China |

| Preceded by Generalissimo of the Military Government of Nationalist China |

Extraordinary President of Nationalist China 1921–1922 |

Succeeded by Himself as Generalissimo of the Nationalist China |

| Preceded by Office created |

Generalissimo of the National Government of Nationalist China 1923–1925 |

Succeeded by Hu Hanmin Acting |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Song Jiaoren as President of the Kuomintang |

Premier of the Kuomintang 1913–1914 |

Succeeded by Himself as Premier of the Chinese Revolutionary Party |

| Preceded by Himself as Premier of the Chinese Revolutionary Party |

Premier of the Kuomintang of China 1919–1925 |

Succeeded by Zhang Renjie as Chairman |