Wrocław

Wrocław (UK: /ˈvrɒtswɑːf/ VROTS-wahf, US: /ˈvrɔːts-wɑːf, -lɑːf, -lɑːv/ VRAWTS-wahf, -lahf, -lahv,[2][3][4] Polish: [ˈvrɔt͡swaf] (![]()

![]()

Wrocław | |

|---|---|

.jpg)   | |

| Motto(s): Wrocław: miasto spotkań (Polish "Wrocław – The Meeting Place")

| |

Wrocław  Wrocław  Wrocław | |

| Coordinates: 51°6′N 17°2′E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| Established | 10th century |

| City rights | 1214 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jacek Sutryk (KO) |

| Area | |

| • City | 292.92 km2 (113.10 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 155 m (509 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 105 m (344 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2019) | |

| • City | 642,869 |

| • Metro | 1,164,600 |

| • Demonym | Vratislavian |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 50-041 to 54-612 |

| Area code(s) | +48 71 |

| Car plates | DW, DX |

| Website | www |

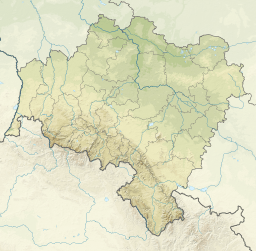

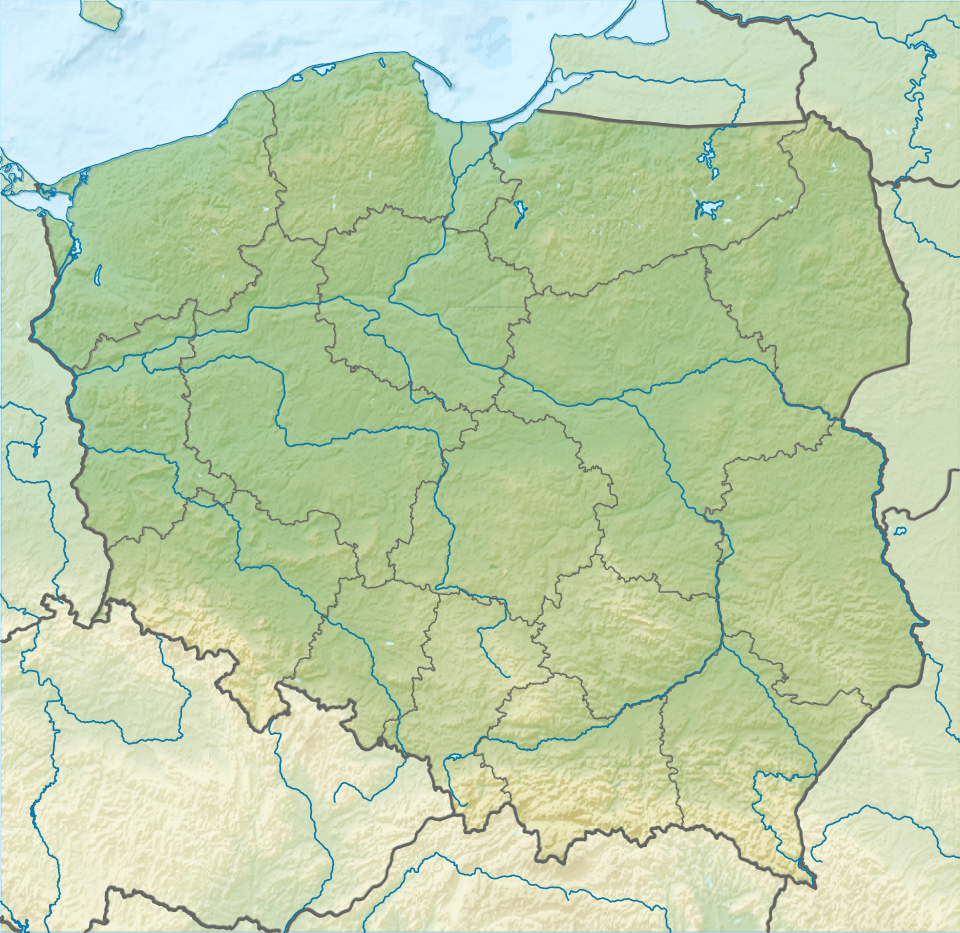

Wrocław is the historical capital of Silesia and Lower Silesia. Today, it is the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. The history of the city dates back over a thousand years;[5] at various times, it has been part of the Kingdom of Poland, the Kingdom of Bohemia, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Prussia and Germany. Wrocław became part of Poland again in 1945 as part of the so-called Recovered Territories as a result of the border changes after the Second World War. This included the flight and expulsion of the pre-war population of the city.

Wrocław is a university city with a student population of over 130,000, making it arguably one of the most youth-oriented cities in the country.[6] Since the beginning of the 20th century, the University of Wrocław, previously Breslau University, has produced 9 Nobel Prize laureates and is renowned for its high quality of teaching.[7][8]

Wrocław is classified as a Gamma- global city by GaWC.[9] It was placed among the top 100 cities in the world for the Mercer Quality of Living Survey and in the top 100 of the smartest cities in the world in the IESE Cities in Motion Index 2017 and 2019 report.[10][11] Wrocław also possesses numerous historical landmarks, including the Main Market Square, Cathedral Island and the Centennial Hall, which is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 1989, 1995 and 2019 Wrocław hosted the European Youth Meetings of the Taizé Community and hosted the Eucharistic Congress in 1997 and the 2012 European Football Championship. In 2016, the city was a European Capital of Culture and the World Book Capital.[12] Also in that year, Wrocław hosted the Theatre Olympics, World Bridge Games and the European Film Awards. In 2017, the city was host to the IFLA Annual Conference and the World Games. In 2019, it was named a UNESCO City of Literature.

Etymology

Traditionally, the city is believed to be named after Duke Vratislav I of Bohemia from the Czech Přemyslid dynasty, who ruled the region between 915 and 921.[13] The city's name first appeared in the 10th century probably as Vratislava. The oldest surviving document containing the recorded name of the city is the chronicle of Thietmar of Merseburg form the early 11th century, which records the city's name as "Wrotizlava", and cites it as a seat of a new bishopric at the Congress of Gniezno. The city's first municipal seal was inscribed with Sigillum civitatis Wratislavie.

The original Old Czech language version of the name was used in Latin documents, as Vratislavia or Wratislavia. In the Polish language, the city's name Wrocław derives from the name Wrocisław, which is the Polish equivalent of the Czech name Vratislav. The earliest variations of this name in the Old Polish language use the letter /l/ instead of /ł/. By the 15th century, the Early New High German variations of the name, Breslau, first began to be used. Despite the noticeable differences in spelling, the numerous German forms were still based on the original Slavic name of the city, with the -Vr- sound being replaced over time by -Br-,[14] and the suffix -slav- replaced with -slau-. These variations included Vratizlau, Wratislau, Wrezlau or Breßlau among others.[15] In other languages, the city's name is: modern Czech: Vratislav, Hungarian: Boroszló, Hebrew: ורוצלב (Vrotsláv), Yiddish: ברעסלוי (Bresloi), Silesian German: Brassel, and Latin: Vratislavia, Wratislavia or Budorgis.[16][17]

People born or resident in the city are known as "Vratislavians" (Polish: wrocławianie). During the German era, the demonym was "Breslauers".

History

In ancient times, there was a place called Budorigum at or near the site of Wrocław. It was already mapped on Claudius Ptolemy's map of AD 142–147. Settlements in the area existed from the 6th century onward during the migration period. The Ślężans, a West Slavic tribe, settled on the Oder river and erected a gord on Ostrów Tumski.

Wrocław originated at the intersection of two trade routes, the Via Regia and the Amber Road. The city was first recognized in the 10th century as Vratislavia on account of the Bohemian duke Vratislav I's stronghold there, hence the name.[13] When in 985, Duke Mieszko I of Poland conquered Silesia, Vratislavia's polonised form over time became Wrocław. The town was mentioned explicitly in the year 1000 AD in connection with its promotion to an episcopal see during the Congress of Gniezno.

Middle Ages

During Wrocław's early history, control over it changed hands between Bohemia (until 992, then 1038–1054) and the Kingdom of Poland (992–1038 and 1054–1202). Following the fragmentation of the Kingdom of Poland, the Piast dynasty ruled the duchy of Silesia. One of the most important events during this period was the foundation of the Diocese of Wrocław by the Polish Duke and from 1025, King Bolesław the Brave in 1000. Along with the Bishoprics of Kraków and Kołobrzeg, Wrocław was placed under the Archbishopric of Gniezno in Greater Poland, founded by Pope Sylvester II through the intercession of Polish Duke Bolesław I the Brave and Emperor Otto III in 1000, during the Gniezno Congress. In the years 1034–1038 the city was affected by Pagan reaction in Poland.[18]

The city became a commercial centre and expanded to Wyspa Piasek (Sand Island), and then onto the left bank of the River Oder. Around 1000, the town had about 1,000 inhabitants.[19] In 1109 during the Polish-German war, Prince Bolesław III Wrymouth defeated the King of Germany Henry V at the Battle of Hundsfeld, stopping the German advance into Poland. The medieval chronicle, Gesta principum Polonorum (1112–1116) by Gallus Anonymus, named Wrocław, along with Kraków and Sandomierz, as one of three capitals of the Polish Kingdom. Also, the Tabula Rogeriana a book written by the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi in 1154, describes Wrocław as one of the Polish cities, alongside Kraków, Gniezno, Sieradz, Łęczyca and Santok.[20]

By 1139, a settlement belonging to Governor Piotr Włostowic (also known as Piotr Włast Dunin) was built, and another on the left bank of the River Oder, near the present site of the University. While the city was largely Polish, it also had communities of Czech Bohemians, Germans, Walloons and Jews.[21][18]

In the 13th century, Wrocław was the political centre of the divided Polish kingdom.[22] In April 1241, during the First Mongol invasion of Poland the city was abandoned by its inhabitants and burnt down for strategic reasons. During the battles with the Mongols Wrocław Castle was successfully defended by Henry II the Pious.[23]

After the Mongol invasion the town was partly populated by German settlers who, in the ensuing centuries gradually became its dominant population.[24] The city, however, retained its multi-ethnic character, a reflection of its importance as a trading post on the junction of the Via Regia and the Amber Road.[25]

With the influx of settlers the town expanded and in 1242 came under German town law. The city council used both Latin and German, and the early forms of the name "Breslau", the German name of the city, appeared for the first time in its written records.[24] The enlarged town covered around 60 hectares (150 acres), and the new main market square, surrounded by timber-frame houses, became the trade centre of the town. The original foundation, Ostrów Tumski, became its religious centre. The city gained Magdeburg rights in 1261. While the Polish Piast dynasty remained in control of the region, the ability of the city council to govern itself independently increased.[26] In 1274 prince Henryk IV Probus gave the city its staple right. In the 13th century, two Polish monarchs were buried in Wrocław churches founded by them, Henry II the Pious in the St. Vincent church[27] and Henryk IV Probus in the Holy Cross church.[28]

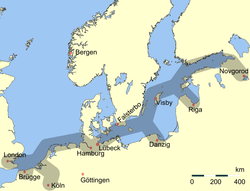

Wrocław, which for 350 years had been mostly under Polish hegemony, fell in 1335, after the death of Henry VI the Good, to the Kingdom of Bohemia, then a part of the Holy Roman Empire. Between 1342 and 1344, two fires destroyed large parts of the city. In 1387 the city joined the Hanseatic League. On 5 June 1443, the city was rocked by an earthquake, estimated at ca. 6 on the Richter scale, which destroyed or seriously damaged many of its buildings.

Between 1469 and 1490 it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary and king Matthias Corvinus was said to have had a mistress who bore him a son. In 1474, after almost a century, the city left the Hanseatic League. Also in 1474, the city was besieged by combined Polish-Czech forces, however in November 1474 Kings Casimir IV of Poland, his son Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Matthias Corvinus of Hungary met in the nearby village of Muchobór Wielki (present-day district of Wrocław) and a in December 1474 a ceasefire was signed, according to which the city remained under Hungarian rule.[29] The following year was marked by the publication in Wrocław of the Statuta Synodalia Episcoporum Wratislaviensium (1475) by Kasper Elyan, the first ever Incunable in Polish, containing the proceedings and prayers of the Wrocław bishops.

Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In the 16th century, Breslauer Schöps beer style was created in Wrocław.

The Protestant Reformation reached the city in 1518 and it converted to the new rite. However, from 1526 Silesia was ruled by the Catholic House of Habsburg. In 1618, it supported the Bohemian Revolt out of fear of losing the right to religious freedom. During the ensuing Thirty Years' War, the city was occupied by Saxon and Swedish troops, and lost 18,000 of 40,000 citizens to the plague.

The emperor brought in the Counter-Reformation by encouraging Catholic orders to settle in the city, starting in 1610 with the Franciscans, followed by the Jesuits, then Capuchins, and finally Ursuline nuns in 1687.[13] These orders erected buildings which shaped the city's appearance until 1945. At the end of the Thirty Years' War, however, it was one of only a few Silesian cities to stay Protestant.

The Polish Municipal school opened in 1666 and lasted until 1766. Precise record-keeping of births and deaths by the city fathers led to the use of their data for analysis of mortality, first by John Graunt and then based on data provided to him by Breslau professor Caspar Neumann, by Edmond Halley.[30] Halley's tables and analysis, published in 1693, are considered to be the first true actuarial tables, and thus the foundation of modern actuarial science. During the Counter-Reformation, the intellectual life of the city flourished, as the Protestant bourgeoisie lost some of its dominance to the Catholic orders as patrons of the arts.

Enlightenment period

The city became the centre of German Baroque literature and was home to the First and Second Silesian school of poets.[31] In the 1740s the Kingdom of Prussia annexed the city and most of Silesia during the War of the Austrian Succession. Habsburg empress Maria Theresa ceded most of the territory in the Treaty of Breslau in 1742 to Prussia. Austria attempted to recover Silesia with Breslau during the Seven Years' War and at the Battle of Breslau, but unsuccessfully. In 1766, Giacomo Casanova stayed in Breslau.

Napoleonic Wars

During the Napoleonic Wars, it was occupied by the Confederation of the Rhine army. The fortifications of the city were levelled and monasteries and cloisters were seized.[13] The Protestant Viadrina European University of Frankfurt (Oder) was relocated to Breslau in 1811, and united with the local Jesuit University to create the new Silesian Frederick-William University (Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelm-Universität, now the University of Wrocław). The city became a centre of the German Liberation movement against Napoleon, and a gathering place for volunteers from all over Germany. The city was the centre of Prussian mobilisation for the campaign which ended at the Battle of Leipzig.[32]

Prussia and Germany

The Confederation of the Rhine had increased prosperity in Silesia and in the city. The removal of fortifications opened room for the city to grow beyond its former limits. Breslau became an important railway hub and industrial centre, notably for linen and cotton manufacture and the metal industry. The reconstructed university served as a major centre of science. Johannes Brahms wrote his Academic Festival Overture to thank the university for an honorary doctorate awarded in 1881.

In 1821, (Arch)Diocese of Breslau withdrew from dependence on the Polish archbishopric of Gniezno and Breslau became an exempt see. On 10 October 1854, the Jewish Theological Seminary opened. The institution was the first modern rabbinical seminary in Central Europe. In 1863 the brothers Karl and Louis Stangen founded the travel agency Stangen, the second travel agency in the world.[33]

The Unification of Germany in 1871 turned Breslau into the sixth-largest city in the German Empire. Its population more than tripled to over half a million between 1860 and 1910. The 1900 census listed 422,709 residents.

In 1890, construction began of Breslau Fortress as the city's defences. Important landmarks were inaugurated in 1910, the Kaiser bridge (today Grunwald Bridge) and the Technical University, which now houses the Wrocław University of Technology. The 1900 census listed 98% of the population as German-speakers, with 5,363 Polish-speakers (1.3%), and 3,103 (0.7%) as bilingual in German and Polish.[34] The population was 58% Protestant, 37% Catholic (including at least 2% Polish)[35] and 5% Jewish (totaling 20,536 in the 1905 census).[34] The Jewish community of Breslau was among the most important in Germany, producing several distinguished artists and scientists.[36]

From 1912, the head of the University's Department of Psychiatry and director of the Clinic of Psychiatry (Königlich Psychiatrischen und Nervenklinik) was Alois Alzheimer and, that same year, professor William Stern introduced the concept of IQ.

.jpg)

In 1913, the newly built Centennial Hall housed an exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of the historical German Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and the first award of the Iron Cross.

Following the First World War, Breslau became the capital of the newly created Prussian Province of Lower Silesia of the Weimar Republic in 1919. After the war the Polish community began holding masses in Polish at the Church of Saint Anne, and, as of 1921, at St. Martin's and a Polish School was founded by Helena Adamczewska.[37] In 1920 a Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square.

In August 1920, during the Polish Silesian Uprising in Upper Silesia, the Polish Consulate and School were destroyed, while the Polish Library was burned down by a mob. The number of Poles as a percentage of the total population fell to just 0.5% after the re-emergence of Poland as a state in 1918, when many moved to Poland.[35] Antisemitic riots occurred in 1923.[38]

The city boundaries were expanded between 1925 and 1930 to include an area of 175 km2 (68 sq mi) with a population of 600,000. In 1929, the Werkbund opened WuWa (German: Wohnungs- und Werkraumausstellung) in Breslau-Scheitnig, an international showcase of modern architecture by architects of the Silesian branch of the Werkbund. In June 1930, Breslau hosted the Deutsche Kampfspiele, a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I. The number of Jews remaining in Breslau fell from 23,240 in 1925 to 10,659 in 1933.[39] Up to the beginning of World War II, Breslau was the largest city in Germany east of Berlin.[40]

Known as a stronghold of left wing liberalism during the German Empire, Breslau eventually became one of the strongest support bases of the Nazis, who in the 1932 elections received 44% of the city's vote, their third-highest total in all Germany.[41][42]

KZ Dürrgoy, one of the first concentration camps in the Third Reich, was set up in Breslau in 1933.

After Hitler's appointment as German Chancellor in 1933, political enemies of the Nazis were persecuted, and their institutions closed or destroyed. The Gestapo began actions against Polish and Jewish students (see: Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau), Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. Arrests were made for speaking Polish in public, and in 1938 the Nazi-controlled police destroyed the Polish cultural centre.[43][44] In September 1941 the city's 10,000 Jews were displaced from their homes and soon deported to camps. Few survived the Holocaust.[45] Also many other people seen as "undesirable" by the Third Reich were sent to concentration camps.[43] A network of concentration camps and forced labour camps was established around Breslau, to serve industrial concerns, including FAMO, Junkers and Krupp. Tens of thousands were imprisoned there.[46]

The last big event organised by the National Socialist League of the Reich for Physical Exercise, called Deutsches Turn-und-Sportfest (Gym and Sports Festivities), took place in Breslau from 26 to 31 July 1938. The Sportsfest was held to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the German Wars of Liberation against Napoleon's invasion.[47]

Second World War

For most of World War II, the fighting did not affect Breslau. During the war, the Germans opened the graves of medieval Polish monarchs and local dukes to carry out anthropological research for propaganda purposes, wanting to demonstrate their "racial purity".[27] The remains were transported to other places by the Germans, and have not been found to this day.[27] In 1941 the remnants of the pre-war Polish minority in the city, as well as Polish slave labourers, organised a resistance group called Olimp. The organisation gathered intelligence, carrying out sabotage and organising aid for Polish slave workers. As the war continued, refugees from bombed-out German cities, and later refugees from farther east, swelled the population to nearly one million,[48] including 51,000 forced labourers in 1944, and 9,876 Allied PoWs. At the end of 1944 an additional 30,000–60,000 Poles were moved into the city after Germans crushed the Warsaw Uprising.[49]

During the war the Germans operated four subcamps of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in the city.[50] Approximately 3,400-3,800 men of different nationalities were imprisoned in three subcamps, among them Poles, Russians, Italians, Frenchmen, Ukrainians, Czechs, Belgians, Yugoslavs, Chinese, and about 1,500 Jewish women were imprisoned in the fourth camp.[50] Many prisoners died, and the remaining were evacuated to the main camp of Groß-Rosen in January 1945.[50]

In February 1945 the Soviet Red Army approached the city. Gauleiter Karl Hanke declared the city a Festung (fortress) to be held at all costs. Hanke finally lifted a ban on the evacuation of women and children when it was almost too late. During his poorly organised evacuation in January 1945, 18,000 people froze to death in icy snowstorms and −20 °C (−4 °F) weather. By the end of the Battle of Breslau (February–May 1945), half the city had been destroyed. An estimated 40,000 civilians lay dead in the ruins of homes and factories. After a siege of nearly three months, Festung Breslau capitulated on 6 May 1945, two days before the end of the war.[51] In August the Soviets placed the city under the control of German anti-fascists.[52]

Following on from the Yalta Conference held in February 1945 when the new Geopolitics of Central Europe were decided, the terms of the Potsdam Conference decreed that with almost all of Lower Silesia, the city would become part of Poland in exchange for Poland's loss of the city of Lwów along with the massive territory of Kresy to the East. The Polish name of "Wrocław" was declared official. There had been discussion among the Western Allies to place the southern Polish-German boundary on the Glatzer Neisse, which meant post-war Germany would have been allowed to retain approximately half of Silesia, including Breslau. However, the Soviets insisted the border be drawn at the Lusatian Neisse farther west.

After the war

In August 1945, the city had a German population of 189,500, and a Polish population of 17,000. After World War II the region once again became part of Poland under territorial changes demanded by the Soviet Union in the Potsdam Agreement.[52] The town's inhabitants, who had not fled or who had safely returned to their home town after the war officially had ended, were expelled between 1945 and 1949 in accordance to the Potsdam Agreement and were settled in the Soviet occupation zone and Allied Occupation Zones in the remainder of Germany. The city's last pre-war German school was closed in 1963.

The Polish population was dramatically increased by the resettlement of Poles during postwar population transfers during the forced deportations from Polish lands annexed by the Soviet Union in the east region, some of whom came from Lviv (Lwów), Volhynia and Vilnius Region. A small German minority (about 1,000 people, or 2% of the population) remains in the city, so that today the relation of Polish to German population is the reverse of the relation 100 years ago.[53] Traces of the German past such as inscriptions and signs were removed.[54]

Wrocław is now a unique European city of mixed heritage, with architecture influenced by Bohemian, Austrian and Prussian traditions, such as Silesian Gothic and its Baroque style of court builders of Habsburg Austria (Fischer von Erlach). Wrocław has a number of notable buildings by German modernist architects including the famous Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia or Jahrhunderthalle; 1911–1913) designed by Max Berg. In 1948, Wrocław organised the Recovered Territories Exhibition and the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace. Picasso's lithograph, La Colombe (The Dove), a traditional, realistic picture of a pigeon, without an olive branch, was created on a napkin at the Monopol Hotel in Wrocław during the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace.

In 1963, Wrocław was declared a closed city because of a smallpox epidemic.

In 1982, during martial law in Poland, the anti-communist underground organizations, Fighting Solidarity and Orange Alternative were founded in Wrocław. Wrocław's dwarves made of bronze famously grew out of and commemorate Orange Alternative.

In 1983 and 1997, Pope John Paul II visited the city.

PTV Echo, the first non-state television station in Poland and in the post-communist countries, began to broadcast in Wrocław on 6 February 1990.

In May 1997, Wrocław hosted the 46th International Eucharistic Congress.

In July 1997, the city was heavily affected by a flood of the River Oder, the worst flooding in post-war Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic. About one-third of the area of the city was flooded.[55] An earlier equally devastating flood of the river took place in 1903.[56] A small part of the city was also flooded during the flood in 2010. From 2012 to 2015, the Wrocław water node was renovated and redeveloped to prevent further flooding. It cost more than 900 million PLN (c. 220 million euro).

Three matches in Group A of the UEFA Euro 2012 championship were played in the then newly constructed Municipal Stadium in Wrocław.

In 2016, Wrocław was European Capital of Culture.

In 2017, Wrocław hosted the 2017 World Games.

Wrocław won the European Best Destination title in 2018.[57]

Environment

The city stretches for 26.3 kilometers on the east–west line and 19.4 kilometers on the north–south line.

Air pollution

Wrocław is one of the most polluted European and Polish cities. In a report by French Respire organization from 2014, Wrocław was named the eighth most polluted European city, with 166 days of bad air quality yearly.[58] Air pollution mainly occurs in winter.

According to the Wrocław University research from 2017, high concentration of particular matters (PM2.5 and PM 10) in the air causes 942 premature deaths of Wrocław inhabitants per year.[59] Air pollution also causes 3297 cases of bronchitis among Wrocław's children per year.[59]

84% of Wrocław inhabitants think that air pollution is a serious social problem, according to the poll from May 2017. 73% of people think, that air quality is bad.[60]

In 2012, there were 71 days, when the PM10 standards, set by Cleaner Air For Europe Directive, were exceeded. In 2014, there were 104 such days.[61]

In February 2018, Wrocław was the most polluted city on Earth, according to the Airvisual website, which measures the air quality index.[62][63]

In 2014, inhabitants founded an organization, called the Lower Silesian Smog Alert (Dolnośląski Alarm Smogowy, DAS), to tackle the air pollution problem. Its goals are to educate the public and to reduct emission of harmful substances.[64]

Climate

According to Köppen's original definition, Wrocław has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb). However it is common in the literature published in English to use the 0 °C isotherm for the coldest month (as opposed to the original −3 °C) as the boundary between the C and D types. Based on that definition, Wrocław has a humid continental climate (Dfb). It is one of the warmest cities in Poland. Lying in the Silesian Lowlands between Trzebnickie Hills and the Sudetes, the mean annual temperature is 9.04 °C (48 °F). The coldest month is January (average temperature −0.7 °C), with snow being common in winter, and the warmest is July (average temperature 18.9 °C). The highest temperature in Wrocław was recorded on 19 August 1892[65] and 8 August 2015 (+38.9 °C).[66] The previous records were +38 °C on 27 June 1935 and +37.9 °C on 31 July 1994. The lowest temperature was recorded on 11 February 1956 (−32 °C).

| Climate data for Wrocław (Copernicus Airport), elevation: 120 m, 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.3 (61.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

38.9 (102.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −29.4 (−20.9) |

−32 (−26) |

−22.1 (−7.8) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−4 (25) |

−6 (21) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−32 (−26) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29 (1.1) |

24 (0.9) |

36 (1.4) |

32 (1.3) |

59 (2.3) |

62 (2.4) |

95 (3.7) |

59 (2.3) |

46 (1.8) |

36 (1.4) |

32 (1.3) |

29 (1.1) |

534 (21.0) |

| Average precipitation days | 16 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 157 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 80 | 76 | 69 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 71 | 77 | 82 | 86 | 85 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57 | 82 | 126 | 197 | 247 | 245 | 257 | 250 | 167 | 119 | 66 | 51 | 1,864 |

| Source: [67][68][69][70][71] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Wrocław (Copernicus Airport), elevation: 120 m, 1961–1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

8.3 (47.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −5.3 (22.5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.0 (−22.0) |

−27.0 (−16.6) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 28 (1.1) |

26 (1.0) |

26 (1.0) |

39 (1.5) |

64 (2.5) |

80 (3.1) |

84 (3.3) |

78 (3.1) |

48 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

43 (1.7) |

34 (1.3) |

590 (23.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.3 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 99.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 49.0 | 65.0 | 107.0 | 142.0 | 198.0 | 194.0 | 205.0 | 197.0 | 139.0 | 108.0 | 52.0 | 39.0 | 1,495 |

| Source: NOAA[72] | |||||||||||||

Fauna

In Wrocław, the presence of over 200 species of birds has been registered, of which over 100 have nesting places there. As in other large Polish cities, the most numerous are pigeons. Other common species are the sparrow, tree sparrow, siskin, rook, crow, jackdaw, magpie, swift, martin, swallow, kestrel, mute swan, mallard, coot, merganser, black-headed gull, great tit, blue tit, long-tailed tit, greenfinch, hawfinch, collared dove, common wood pigeon, fieldfare, redwing, common starling, grey heron, white stork, common chaffinch, blackbird, jay, nuthatch, bullfinch, cuckoo, waxwing, lesser spotted woodpecker, great spotted woodpecker, white-backed woodpecker, white wagtail, blackcap, black redstart, old world flycatcher, emberizidae, goldfinch, western marsh harrier, little bittern, common moorhen, reed bunting, remiz, great reed warbler, little crake, little ringed plover and white-tailed eagle.

In addition, the city is notoriously plagued by bold rats (especially in the Market Square with its many eateries). Otherwise, due to the proximity of wooded areas there are hedgehogs, foxes, wild boar, bats, martens, squirrels, deer, hares, beavers, polecats, otters, badgers, weasels, stoats and raccoon dogs. There are also occasional sightings of escaped muskrat, american mink and raccoon.

Flora

There are 44 parks and public green spaces totalling 800 hectares in the city. Most notable are Szczytnicki Park, Park Południowy and Wladyslaw Anders Park. In addition, Wrocław University runs an historical Botanical garden (founded in 1811), with a salient Alpine garden, a lake and a valley.[73]

Water

The city lies on the Oder River and its four tributaries, which supply it within the city limits: Bystrzyca, Oława, Ślęza and Widawa. In addition, the Dobra River and many streams flow through the city.

Wrocław draws drinking water from the water–bearing areas supplied with groundwater, and (via the Nysa-Oława Canal) from the Oława and Nysa Kłodzka rivers.

The city has a sewage treatment plant on the Janówek estate.

Government and politics

Wrocław is the capital city of Lower Silesian Voivodeship, a province (voivodeship) created in 1999. It was previously the seat of Wrocław Voivodeship. The city is a separate urban gmina and city-county (powiat). It is also the seat of Wrocław County, which adjoins but does not include the city.

Districts

Wrocław was previously subdivided into five boroughs (dzielnica):

- Fabryczna ("Factory Quarter")

- Krzyki, (German: Krietern, meaning "Wranglers")

- Psie Pole (German: Hundsfeld, "Dogs' Field", named so after the alleged Battle of Psie Pole or poor quality of the fields)

- Stare Miasto (old town)

- Śródmieście (midtown)

However, the city is now divided into 48 osiedles (districts): Bieńkowice, Biskupin-Sępolno-Dąbie-Bartoszowice, Borek, Brochów, Gaj, Gajowice, Gądów-Popowice Płd., Grabiszyn-Grabiszynek, Huby, Jagodno, Jerzmanowo-Jarnołtów-Strachowice-Osiniec, Karłowice-Różanka, Klecina, Kleczków, Kowale, Krzyki-Partynice, Księże, Kuźniki, Leśnica, Lipa Piotrowska, Maślice, Muchobór Mały, Muchobór Wielki, Nadodrze, Nowy Dwór, Ołbin, Ołtaszyn, Oporów, Osobowice-Rędzin, Pawłowice, Pilczyce-Kozanów-Popowice Płn., Plac Grunwaldzki, Polanowice-Poświętne-Ligota, Powstańców Śląskich, Pracze Odrzańskie, Przedmieście Oławskie, Przedmieście Świdnickie, Psie Pole-Zawidawie, Sołtysowice, Stare Miasto, Strachocin-Swojczyce-Wojnów, Szczepin, Świniary, Tarnogaj, Widawa, Wojszyce, Zacisze-Zalesie-Szczytniki, and Żerniki.

Municipal government

Wrocław is currently governed by the city's mayor and a municipal legislature known as the city council. The city council is made up of 39 councilors and is directly elected by the city's inhabitants. The remit of the council and president extends to all areas of municipal policy and development planning, up to and including development of local infrastructure, transport and planning permission. However, it is not able to draw taxation directly from its citizens, and instead receives its budget from the Polish national government whose seat is in Warsaw.

The city's current mayor is Jacek Sutryk, who has served in this position since 2018. The first mayor of Wrocław after World War II was Bolesław Drobner, who was appointed to this position on March 14, 1945, i.e. before the surrender of Festung Breslau.

Economy

Wrocław is the second wealthiest city in Poland after Warsaw.[74] The city is also home to the largest number of leasing and debt collection companies in the country, including the largest European Leasing Fund as well as numerous banks. Due to the proximity of the borders with Germany and the Czech Republic, Wrocław and the region of Lower Silesia is a large import and export partner with these countries.

Wrocław's industry manufactures buses, railroad cars, home appliances, chemicals, and electronics. The city houses factories and development centers of many foreign and domestic corporations, such as WAGO Kontakttechnik, Siemens, Bosch, Whirlpool Corporation, Nokia Networks, Volvo, HP, IBM, Google, Opera Software, Bombardier Transportation, WABCO and others. Wrocław is also the location of offices for large Polish companies including Getin Holding, AmRest, Polmos, and MCI Management SA. Additionally, Kaufland Poland has its main headquarters in the city.[75]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the city has had a developing high-tech sector. Many high-tech companies are located in the Wrocław Technology Park, such as Baluff, CIT Engineering, Caisson Elektronik, ContiTech, Ericsson, Innovative Software Technologies, IBM, IT-MED, IT Sector, LiveChat Software, Mitsubishi Electric, Maas, PGS Software, Technology Transfer Agency Techtra and Vratis. In Biskupice Podgórne (Community Kobierzyce) there are factories of LG (LG Display, LG Electronics, LG Chem, LG Innotek), Dong Seo Display, Dong Yang Electronics, Toshiba, and many other companies, mainly from the electronics and home appliances sectors, while the Nowa Wieś Wrocławska factory and distribution center of Nestlé Purina and factories a few other enterprises.

The city is the seat of Wrocław Research Centre EIT+, which contains, inter alia, geological research laboratories to the unconventional and Lower Silesian Cluster of Nanotechnology.[76] The logistics centers DHL, FedEx and UPS are based in Wrocław.[77] Furthermore, it is a major center for the pharmaceutical industry (U.S. Pharmacia, Hasco-Lek, Galena, Avec Pharma, 3M, Labor, S-Lab, Herbapol, and Cezal).

Wrocław is home to Poland's largest shopping mall – Bielany Avenue (pl. Aleja Bielany) and Bielany Trade Center, located in Bielany Wrocławskie where stores such as Auchan, Decathlon, Leroy Merlin, Makro, Tesco, IKEA, Jula, OBI, Castorama, Black Red White, Poco, E. Wedel, Cargill, Prologis and Panattoni can be found.[78]

In February 2013, Qatar Airways launched its Wrocław European Customer Service.[79]

Shopping malls

- Wroclavia

- Galeria Handlowa Sky Tower

- Galeria Dominikańska

- Pasaż Grunwaldzki

- Arkady Wrocławskie

- Centrum Handlowe Borek

- Tarasy Grabiszyńskie

- Magnolia Park

- Wrocław Fashion Outlet

- Factoria Park

- Centrum Handlowe Korona

- Renoma, a 1930s department store of architectural interest over and above its shopping value

- Feniks

- Wrocław Market Hall

- Marino

- Park Handlowy Młyn

- Family Point

- Ferio Gaj

- Aleja Bielany in Bielany Wrocławskie (suburb of Wrocław) – the largest shopping mall in Poland

Major corporations

- 3M

- Akwawit–Polmos S.A. – plant "Wratislavia vodka"

- Bombardier Transportation Polska

- The Bank of New York Mellon

- CH Robinson Worldwide

- Crédit Agricole Poland

- Credit Suisse[80]

- Deichmann

- DeLaval Operations Poland

- DHL

- Dolby Labs

- Ernst & Young

- Qatar Airways

- Gigaset Communications

- Hewlett Packard

- IBM[81]

- KGHM Polska Miedź

- LiveChat Software

- LG Electronics

- McKinsey & Company

- Microsoft[82]

- National Bank of Poland

- Nokia Networks

- Olympus Business Services Europe

- Opera Software

- Parker Hannifin

- PZ Cussons Polska S.A.

- PZU

- QAD

- Qiagen

- Robert Bosch GmbH

- SAP Polska

- Santander Consumer Bank

- Siemens

- Südzucker

- Tieto

- UBS

- United Technologies Corporation

- Viessmann

- Volvo Polska sp. z o.o.

- WABCO Polska

- Whirlpool Polska S.A.

Transport

Wrocław is a major road hub. The city is skirted on the south by the A4 highway, which allows for a quick connection with Upper Silesia, Kraków, and further east to Ukraine, and Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin to the west. The A8 highway (Wrocław ring road) around the west and north of the city connects the A4 highway with the S5 express road that leads to Poznań, Bydgoszcz and S8 express road that leads to Oleśnica, Łódź, Warsaw, Białystok and National Road 5 and National Road 8 to the Czech Republic. Under construction is the eastern part of the Wrocław ring road.

The city is served by Copernicus Airport Wrocław (airport code WRO) which handles flights from LOT Polish Airlines, Buzz, Ryanair, Wizz Air, Lufthansa, Eurowings, Air France, KLM, Scandinavian Airlines, Swiss International Air Lines, and Norwegian Air Shuttle.

The main rail station is Wrocław Główny, which is the largest railway station in Poland (21,2 million passengers a year).[83] The station is supported by PKP Intercity, Polregio, Koleje Dolnośląskie and Leo Express.

Wrocław has direct rail connections with:

- Warsaw – 3,5 h,

- Kraków – 3 h,

- Gdańsk – 5 h,

- Poznań – 2 h,

- Szczecin – 6 h,

- Berlin – 4 h,

- Prague – 4,5 h,

- Vienna – 7 h,

- Bratislava – 6 h

- Budapest – 9 h

Adjacent to the railway station, is a central bus station located in the basement of the shopping mall of "Wroclavia", with services offered by PKS, Flixbus, Sindbad, and others.

Public transport in Wrocław includes bus lines and 23 tram lines operated by Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne (MPK, the Municipal Transport Company).[84] Rides are paid for, tickets can be bought above kiosks and vending machines, which are located at bus stops and in the vehicles. The tickets are available for purchase in the electronic form via payment card or mobile (mPay, SkyCash, Mobill). Tickets are one-ride or temporary (0.5h, 1h, 1.5h, 24h, 48h, 72h, 168h).

Over a dozen traditional taxicab firms and Uber, iTaxi, Bolt, Free Now operate in the city. In the city there is an e-systems the firms of Lime, Bird and Hive Free Now motorized scooters rental using a mobile application.

There are 1200 km of cycling paths including about 100 km paths on flood embankments. Wrocław has a bike rental network, Wrocław City Bike. It has 2000 bicycles and 200 self-service stations. In addition to regular bicycles, tandem, cargo, electric, folding, tricycles, children's, and handbikes are available, operating every year from 1 March to 30 November. During winter (December – February) 200 bikes are available in the system.

Electronic car rental systems include "Traficar", "Panek CarSharing" (hybrid cars),[85][86] "GoScooter" and "hop.city" electric scooters using the mobile application.

In 2013, Polinka, a gondola lift over the Oder, started to operate.[87] Wrocław also has a river port on the Oder and several marinas.

Demographics

Population

Religion

Wrocław's population is predominantly Roman Catholic, as the rest of Poland. The diocese was founded in the city as early as 1000, it was one of the first dioceses in the country at that time. Now the city is the seat of a Catholic Archdiocese.

Before World War II, Breslau had a majority of Protestants, a large Roman Catholic and a small Jewish minority. In 1939, of 620,976 inhabitants 368,464 were Protestants (United Protestants—mostly Lutherans and minority Reformed—in the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union), 193,805 Catholics, 2,135 other Christians and 10,659 Jews. Post-war resettlements from Poland's ethnically and religiously more diverse former eastern territories (known in Polish as Kresy) and the eastern parts of post-1945 Poland (see Operation Vistula) account for a comparatively large portion of Greek Catholics and Orthodox Christians of mostly Ukrainian and Lemko descent. Wrocław is also unique for its "Dzielnica Czterech Świątyń" (Borough of Four Temples) — a part of Stare Miasto (Old Town) where a Synagogue, a Lutheran Church, a Roman Catholic church and an Eastern Orthodox church stand near each other. Other Christian denominations present in Wrocław include: Adventist, Baptist, Free Christians, Jehovah's Witnesses, Latter-day Saints, Methodist and Pentecostal. There are also minor associations practicing and promoting Rodnovery neopaganism.[88][89]

In 2007, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Wrocław established the Pastoral Centre for English Speakers, which offers Mass on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, as well as other sacraments, fellowship, retreats, catechesis and pastoral care for all English-speaking Catholics and non-Catholics interested in the Catholic Church. The Pastoral Centre is under the care of Order of Friars Minor, Conventual (Franciscans) of the Kraków Province in the parish of St Charles Borromeo (Św Karol Boromeusz).

Wrocław had the third largest Jewish population of all cities in Germany before World War II.[90] Its White Stork Synagogue was built in 1840.[90] It was only rededicated in 2010.[90] Four years later, in 2014, it celebrated its first ordination of four rabbis and three cantors since the Second World War.[90] The Polish authorities together with the German Foreign Minister attended the official ceremony.[90]

Education

Wrocław is the third largest educational centre of Poland, with 135,000 students in 30 colleges which employ some 7,400 staff.[91] List of ten public colleges and universities:

- Wrocław University (Uniwersytet Wrocławski):[92] over 47,000 students, ranked fourth among public universities in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[93]

- Wrocław University of Technology (Politechnika Wrocławska):[94] over 40,000 students, the best university of technology in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[95]

- Wrocław Medical University (Uniwersytet Medyczny we Wrocławiu)[96]

- University School of Physical Education in Wrocław[97]

- Wrocław University of Economics (Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu)[98] over 18,000 students, ranked fifth best among public economic universities in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[99]

- Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu):[100] over 13,000 students, ranked third best among public agricultural universities in Poland by the "Wprost" weekly ranking in 2007[101]

- Academy of Fine Arts in Wrocław (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych we Wrocławiu),[102]

- Karol Lipiński University of Music (Akademia Muzyczna im. Karola Lipińskiego we Wrocławiu)[103]

- Ludwik Solski Academy for the Dramatic Arts, Wrocław Campus (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Teatralna w Krakowie filia we Wrocławiu)[104]

- The Tadeusz Kościuszko Land Forces Military Academy (Wyższa Szkoła Oficerska Wojsk Lądowych)[105]

Private universities:

- Wyższa Szkoła Handlowa (University of Business in Wrocław )

- University of Social Sciences and Humanities (SWPS Uniwersytet Humanistycznospołeczny)

- University of Law (Wyższa Szkoła Prawa)[106]

Other cultural institutions:

- Alliance Française in Wrocław

- Austrian Institute in Wrocław

- British Council in Wrocław

- Dante Alighieri Society in Wrocław

- Grotowski Institute in Wrocław

Tourism

The Tourist Information Centre (Polish: Centrum Informacji Turystycznej) is located on the Main Market Square (Rynek) in building No. 14. In 2011, Wrocław was visited by about 3 million tourists, and in 2016 about 5 million.[107]

Free wireless Internet (Wi-Fi) is available at a number of places around town.

Market Square during Christmas

Market Square during Christmas Centennial Hall, UNESCO World Heritage Site

Centennial Hall, UNESCO World Heritage Site

.jpg)

Africarium, a part of the Wrocław Zoo

Africarium, a part of the Wrocław Zoo

The Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia, German: Jahrhunderthalle), designed by Max Berg in 1911–1913, is a World Heritage Site listed by UNESCO in 2006.

Kobierzyce is the nearby village where Rudolf Steiner presented the first organic agriculture course in 1924.[108] It was, at the time, called Koberwitz.[108]

A frequent destination for tourists visiting Wrocław is the Sudety Mountains, especially the nearby Mount Ślęża.

Culture

.jpeg)

Old Town

Ostrów Tumski is the oldest part of the city of Wrocław. It was formerly an island (ostrów in Old Polish) known as the Cathedral Island between the branches of the Oder River, featuring the Wrocław Cathedral, built originally in the mid 10th century.

The 13th century Main Market Square (Rynek) features the Old Town Hall. In the north-west corner of the Market Square is St. Elisabeth's Church (Bazylika Św. Elżbiety) with its 91.46 m tower, which has an observation deck (75 m). North of the church are the Shambles with Monument of Remembrance of Animals for Slaughter. Salt Square (now a flower market) is located at the south-western corner of the Market Square. Close to the square, between Szewska and Łaciarska streets, is the 13th century St. Mary Magdalene Church (Kościół Św. Marii Magdaleny).

St. Vincent and St. James' Cathedral and the Holy Cross and St. Bartholomew's Collegiate Church are burial sites of Polish monarchs, Henry II the Pious and Henry IV Probus, respectively.

The Pan Tadeusz Museum, open since May 2016, is located in the House under the Golden Sun at 6, Market Square. The manuscript of the national epos, Pan Tadeusz, is housed there as part of the Ossolineum National Institute, with multimedia and interactive educational opportunities.

Landmarks and places of interest

Wrocław is a major attraction for both local and international tourists. Major landmarks include the Multimedia Fountain, Szczytnicki Park with its Japanese Garden, miniature park and dinosaur park, Botanical Garden in Wrocław, founded in 1811, Poland's largest railway model Kolejkowo, Hydropolis Centre for Ecological Education, University of Wrocław with Mathematical Tower, Church of the Name of Jesus, Wrocław water tower, the Royal Palace, ropes course on the Opatowicka Island, White Stork Synagogue, Old Jewish Cemetery, Cemetery for Italian Soldiers.

Wrocław Zoo, home of the Africarium – the only space devoted solely to exhibiting the fauna of Africa with an oceanarium. It is the oldest zoological garden in Poland established in 1865. It is also the third-largest zoo in the world in terms of the number of animal species on display.

Small passenger vessels on the Oder offer river tours, as do historic trams or the converted open-topped historic buses Jelcz 043.

The Little People

Another interesting way to explore the city is seeking out Wrocław's dwarves, small bronze figurines found across the city, on pavements, walls and even on lampposts. They emerged in 2005 since when, there are upwards of 350 assuming different guises. There is a map to help find them.

Entertainment

The city is well known for its large number of nightclubs and pubs. Many are in or near the Market Square, and in the Niepolda passage, the railway wharf on the Bogusławskiego street. The basement of the old City Hall houses one of the oldest restaurants in Europe—Piwnica Świdnicka (operating since around 1275[109]), while the basement of the new City Hall contains the brewpub Spiż. There are many other craft breweries in Wrocław: three brewpubs – Browar Stu Mostów, Browar Staromiejski Złoty Pies, Browar Rodzinny Prost; two microbrewery – Profesja and Warsztat Piwowarski; and seven contract breweries – Doctor Brew, Genius Loci, Solipiwko, Pol A Czech, Baba Jaga, wBrew, Wielka Wyspa. Every year on the second weekend of June the Festival of Good Beer takes place. It is the biggest beer festival in Poland.

Every year in November and December the Christmas market is held at the Market Square.[110]

Museums

.jpg)

The National Museum at Powstańców Warszawy Square, one of Poland's main branches of the National Museum system, holds one of the largest collections of contemporary art in the country.[111]

Ossolineum is a National Institute and Library incorporating the Lubomirski Museum (pl), partially salvaged from the formerly Polish city of Lwów (now Lviv in Ukraine), containing items of international and national significance. It has a history of major World War II theft of collections after the invasion and takeover of Lwów by the Third Reich and the Soviet Union.

Major museums also include the City Museum of Wrocław (pl), Museum of Bourgeois Art in the Old Town Hall, Museum of Architecture, Archaeological Museum (pl), Museum of Natural History at University of Wrocław, Museum of Contemporary Art in Wrocław, Archdiocese Museum (pl), the Arsenal, Museum of Pharmacy (pl), Post and Telecommunications Museum (pl), Geological Museum (pl), the Mineralogical Museum (pl), Ethnographic Museum (pl).

Wrocław in literature

The history of Wrocław is described in minute detail in the monograph Microcosm: Portrait of a Central European City by Norman Davies and Roger Moorhouse.[112] A number of books have been written about Wrocław following World War II.

Wrocław philologist and writer Marek Krajewski wrote a series of crime novels about detective Eberhard Mock, a fictional character from the city of Breslau.[113] Accordingly, Michał Kaczmarek published Wrocław according to Eberhard Mock – Guide based on the books by Marek Krajewski. In 2011 appeared the 1104-page Lexicon of the architecture of Wrocław and in 2013 a 960-page Lexicon about the greenery of Wrocław. In March 2015 Wrocław filed an application to become a UNESCO's City of Literature.[114]

Films, music and theatre

Wrocław is home to the Audiovisual Technology Center (formerly Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych), the Film Stuntman School, ATM Grupa, Grupa 13, and Tako Media.

Andrzej Wajda, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Sylwester Chęciński, among others, made their film debuts in Wrocław. Numerous movies include: Ashes and Diamonds, The Saragossa Manuscript, Sami swoi, Lalka, A Lonely Woman, Character, Aimée & Jaguar, Avalon, A Woman in Berlin, Suicide Room, The Winner, 80 Million, Run Boy Run, Bridge of Spies, Breaking the Limits.

Numerous Polish TV series were also shot in Wrocław, including Świat według Kiepskich, Pierwsza miłość, Belfer, Four Tank-Men and a Dog, Stawka większa niż życie.

There are several theatres and theatre groups, including Polish Theatre (Teatr Polski) with three stages, and Contemporary Theatre (Wrocławski Teatr Współczesny). The International Theatre Festival Dialog-Wrocław is held every 2 years.

Wrocław's opera traditions are dating back to the first half of the seventeenth century and sustained by the Wrocław Opera, built between 1839 and 1841. Wrocław Philharmonic, established in 1954 by Wojciech Dzieduszycki is also important for music lovers. The National Forum of Music was opened in 2015 and is a famous landmark, designed by the Polish architectural firm, Kurylowicz & Associates.

Sports

The Wrocław area has many popular professional sports teams. The most popular sport today is football, thanks to Śląsk Wrocław – Polish Champion in 1977 and 2012.

In second place is basketball, thanks to Śląsk Wrocław – the award-winning men's basketball team (17 times Polish Champion).

Matches of Group A UEFA Euro 2012's were held at Wrocław at the Municipal Stadium. Matches of EuroBasket 1963 and EuroBasket 2009, as well as 2009 Women's European Volleyball Championship, 2014 FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championship and 2016 European Men's Handball Championship were also held in Wrocław. Wrocław was the host of the 2013 World Weightlifting Championships and will the host World Championship 2016 of Duplicate bridge and World Games 2017, a competition in 37 non-Olympic sport disciplines.

The Olympic Stadium in Wrocław hosts the Speedway Grand Prix of Poland. It is also the home arena of the popular motorcycle speedway club WTS Sparta Wrocław, four-time Polish Champion.

A marathon takes place in Wrocław every year in September.[115] Wrocław also hosts the Wrocław Open, a professional tennis tournament that is part of the ATP Challenger Tour.

Men's sports

- Śląsk Wrocław: men's football team, Polish Championship in Football 1977, 2012; Polish Cup winner 1976, 1987; Polish SuperCup winner 1987, 2012; Polish League Cup winner 2009. Now in Ekstraklasa (Polish Premier League).

- Śląsk Wrocław (previous names: BASCO Śląsk Wrocław, ASCO Śląsk Wrocław, Bergson Śląsk Wrocław, Era Śląsk Wrocław, Deichmann Śląsk Wrocław, Idea Śląsk Wrocław, Zepter Idea Śląsk Wrocław, Zepter Śląsk Wrocław, Śląsk ESKA Wrocław, PCS Śląsk Wrocław, WKS Śląsk Wrocław)—men's basketball team, 17 times Polish Champion, six times runner-up, 14 times third place; 12 times Polish Cup winner.

- Śląsk Wrocław: men's handball team, 15-time Polish Champion.

- WTS Sparta Wrocław: motorcycle speedway team, four-time Polish Champion.

- Gwardia Wrocław: volleyball team, three-time Polish Champion.

- KS Rugby Wrocław: rugby union team.

- Panthers Wrocław: American football team.

Women's sports

- KŚ AZS Wrocław: women's football team.

- AZS AWF Wrocław: women's handball team.

- AZS AE Wrocław: women's table tennis team.

- Ślęza Wrocław: women's basketball team.

Swimming

- Aquapark Wrocław (all year)

- Wrocław SPA Center (all year)

- Orbita (all year)

- swimming pool AWF Wrocław (all year)

- swimming pool WKS Śląsk Wrocław (all year)

- Sports center and swimming "Redeco" (all year)

- Morskie Oko (only in summer)

- Glinianki WakePark Wrocław (Pedalo, Skimboarding, Wakeboarding, Waterskiing)(only in summer)

- Królewiecki pond (only in summer)

- swimming pool Kłokoczyce (only in summer)

- watering place Oporów (only in summer)

- watering place Pawłowice (only in summer)

Notable people

- Alois Alzheimer, psychiatrist and neuropathologist

- Adolf Anderssen, chess master

- Đorđe Andrejević-Kun, painter

- Natalia Avelon, actress

- Max Berg, architect

- Max Bielschowsky, neuropathologist

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, theologian, anti-Nazi dissident

- Edmund Bojanowski, blessed of the Catholic Church

- Max Born, theoretical physicist and mathematician, Nobel laureate

- Leszek Czarnecki, businessman

- Hermann von Eichhorn, Prussian field marshal

- Hermann Fernau, lawyer

- Władysław Frasyniuk, politician

- Hans Freeman, biochemist

- Henryk Gulbinowicz, archbishop

- Jerzy Grotowski, theater director

- Fritz Haber, chemist and Nobel laureate

- Felix Hausdorff, mathematician

- Mirosław Hermaszewski, astronaut

- Hubert Hurkacz, tennis player

- Lech Janerka, musician

- Carl Gotthard Langhans, architect

- Clara Immerwahr, chemist

- Alfred Kerr, German-Jewish critic

- Hedwig Kohn, notable female physicist

- August Kopisch, poet

- Urszula Kozioł, poet

- Heinrich Gerhard Kuhn, physicist

- Marek Krajewski, writer and linguist

- Wojciech Kurtyka, mountaineer

- Aleksandra Kurzak, operatic soprano

- Hugo Lubliner, dramatist

- Mateusz Morawiecki, politician, Prime minister of Poland

- Alexander Moszkowski, satirist, writer and philosopher

- Moritz Moszkowski, composer, pianist, and teacher

- Ruth Neudeck, German SS death camps supervisor and war criminal

- Margaret Pospiech, writer, filmmaker

- Sepp Piontek, football manager

- Michael Oser Rabin, mathematician and computer scientist

- Manfred von Richthofen, fighter pilot

- Tadeusz Różewicz, poet and dramatist

- Wanda Rutkiewicz, mountaineer

- Auguste Schmidt, educationist and feminist

- Marlene Schmidt, Miss Germany 1961, Miss Universe 1961

- Eva Siewert, journalist and lesbian activist

- Angelus Silesius (Johann Scheffler), convertite from Protestantism to Roman Catholicism, mystic and religious poet

- Max Simon, Waffen-SS officer

- Agnes Sorma, actress

- Daniel Speer, author, composer

- Eva Stachniak, writer

- Edith Stein, philosopher and Roman Catholic martyr

- Charles Proteus Steinmetz, electrical engineer

- Fritz Stern, historian

- Julius Stern, composer

- William Stern, psychologist

- August Tholuck, theologian

- Olga Tokarczuk, writer, Nobel laureate in Literature

- Henryk Tomaszewski, mime

- Dagmara Wozniak (born 1988), Polish-American U.S. Olympic sabre fencer

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Wrocław is twinned with:[116][117][118][119][120]

Neighbouring municipalities

Czernica, Długołęka, Kąty Wrocławskie, Kobierzyce, Miękinia, Oborniki Śląskie, Siechnice, Wisznia Mała.

See also

References

Notes

- "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 1 June 2019. Data for territorial unit 0264000.

- "Wroclaw". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "Wrocław" (US) and "Wrocław". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "Wrocław". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "Wrocław-info – oficjalny serwis informacji turystycznej Wrocławia". Wroclaw-info.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Administrator. "Wrocław – Dark Tourism – the guide to dark & weird places around the world". Dark-tourism.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Breslauer Nobelpreisträger". Wroclaw.pl. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Russian Universities Lead 2016 Rankings for EECA Region". Topuniversities.com. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Lboro.ac.uk https://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2018t.html=GaWC. Retrieved 19 May 2017. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "2019 Quality of Living survey". Uk.mercer.com. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- IESE Cities in Motion Index 2019

- Minihane, Joe. "20 beautiful European cities with hardly any tourists". CNN. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Historical Overview of Wrocław – Wrocław in Your Pocket". Inyourpocket.com. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Stanisław Rospond, „Dawny Wrocław i jego okolica w świetle nazewnictwa”, Sobótka, 1970.

- Paul Hefftner: Städtische evangelische Realschule I, Ursprung und Bedeutung der Ortsnamen im Stadtkreise Breslau, 1909, S. 9 ff.

- Grässe, J. G. T. (1861). Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benennungen der bekanntesten Städte etc., Meere, Seen, Berge und Flüsse in allen Theilen der Erde nebst einem deutsch-lateinischen Register derselben. Dresden: G. Schönfeld's Buchhandlung (C. A. Werner). p. 40.

- Wratislavia sive Budorgis celebris Elysiorum metropolis. Sbc.org.pl. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Norman Davies "Mikrokosmos" pages 110–115

- Weczerka, p. 39

- Tadeusz Lewicki, Polska i kraje sąsiednie w świetle „Księgi Rogera” geografa arabskiego z XII w. Al Indrisi’ego, cz.I, Polska Akademia Nauk. Komitet Orientalistyczny, PWN, Kraków 1945.

- Weczerka, p. 41

- Benedykt Zientara (1997). Henryk Brodaty i jego czasy (in Polish). Warsaw: Trio. pp. 317–320. ISBN 978-83-85660-46-0.

- Norman Davies "Mikrokosmos" page 114

- Thum, p. 316

- Norman Davies "Mikrokosmos" page 110

- Piotr Górecki (2007). A Local Society in Transition: The Henryków Book and Related Documents. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. pp. 27, 62. ISBN 978-0-88844-155-3.

- Roman Tomczak. "Gdzie jest szkielet bez głowy?". Gość Legnicki (in Polish). Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Magdalena Lewandowska. "Kolegiata Świętego Krzyża". Niedziela.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Maciej Łagiewski. "Spotkanie królów". Gazeta Wrocławska (in Polish). Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Edmond Halley, An Estimate of the Degrees of the Mortality of Mankind, drawn from curious Tables of the Births and Funerals at the City of Breslaw; with an Attempt to ascertain the Price of Annuities upon Lives, Philosophical Transactions, 196 (London, 1693), p.596-610. Edited by Matthias Böhne". www.pierre-marteau.com.

- "How Wrocław found itself by saving its German-Polish literary heritage – Books – DW – 26.04.2016". DW.COM. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "1813 and the lead up to the Battle of Leipzig – napoleon.org". Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Sharma, K. K. (16 March 1999). Tourism and Culture. Sarup & Sons. p. 57. ISBN 9788176250566.

- Cf. Meyers Großes Konversationslexikon: 20 vols., 6th ed., Leipzig and Vienna: Bibliographisches Institut, 1903–1908, vol. 3: Bismarck-Archipel bis Chemnitz (1903), article: Breslau (Stadt), pp. 394–399, here p. 396. No ISBN

- Harasimowicz, p. 466f

- see Till van Rahden: Jews and Other Germans: Civil Society, Religious Diversity, and Urban Politics in Breslau, 1860–1925, ISBN 978-0-299-22694-7

- Microcosm, page 361

- Davies, Moorhouse, p. 396; van Rahden, Juden, p. 323–6

- "Territorial organisation of Breslau (German)". Verwaltungsgeschichte.de. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- "Thum, G.: Uprooted: How Breslau Became Wroclaw during the Century of Expulsions. (eBook and Paperback)". Press.princeton.edu. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- van Rahden, Till (2008). Jews and other Germans: civil society, religious diversity, and urban politics in Breslau, 1860–1925. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 234.

- Norman Davies, Mikrokosmos, page 369

- Davies, Moorhouse, p. 395

- Kulak, p. 252

- "Breslau, Poland". Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "see article "Concentration Camps in and around Breslau 1940–1945"". Roger Moorhouse. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "Breslau bonczek sportfest". Sportfest1938.prv.pl. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- wroclaw.pl (27 July 2010). "History of Wrocław". Wroclaw.pl. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Norman Davies, Mikrokosmos, page 232

- "Subcamps of KL Gross- Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Festung Breslau (Breslau Fortress) siege by the Soviet Army – photo gallery". Wratislavia.net. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Mazower, M(2008) Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe, Penguin Press P544

- "NTKS Wrocław". Ntkswroclaw.vdg.pl. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Zybura, Von Marek. "Breslau wird Wrocław - Über die Wandlung(en) eines Stadtnamens : literaturkritik.de". literaturkritik.de.

- "1997 great flood of Oder River – photo gallery". Miasta.gazeta.pl. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "1903 great flood of the Oder river – photo gallery". Breslau-wroclaw.de. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "Wrocław z tytułem European Best Destination 2018! – www.wroclaw.pl". Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Największy smog w Europie: Kraków na podium, debiut Wrocławia, Warszawa w dziesiątce <http://www.tvn24.pl>". TVN24.pl. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Wpływ zanieczyszczeń powietrza na zdrowie mieszkańców Dolnego Śląska". Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "73% wrocławian źle ocenia jakość powietrza w mieście". Radio Wrocław. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Ekspert: Po Wrocławiu powinno się już chodzić z maseczką na twarzy. Taki jest smog". Wroclaw.wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Niechlubne zwycięstwo Wrocławia. Jest na czele najbardziej zanieczyszczonych miast na świecie [ZDJĘCIA]". Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Dolnośląski Alarm Smogowy: Wrocław był w piątek najbardziej zanieczyszczonym miastem na świecie!". Radio Wrocław. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Ogłosili Dolnośląski Alarm Smogowy. Będą walczyć o czystsze powietrze we Wrocławiu". Tuwroclaw.com. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Rekordy ciepła w Polsce. Zobacz, gdzie i kiedy było najcieplej". tvnmeteo.tvn24.pl. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "We Wrocławiu padł rekord ciepła: 38,9 stopni Celsjusza". Gazetawroclawska.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "КЛИМАТ ВРОЦЛАВА". pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- "Averages". Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "32 stopnie we Wrocławiu. Padł rekord z 1968 Roku". Tvnmeteo.tvn24.pl. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Rekordy temperatury w Polsce – Pogoda i Klimat". Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Aktualne dane pomiarowe – Pogoda i Klimat, Prognozy Numeryczne". Archived from the original on 3 October 2017.

- "Wroclaw (12424) – WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 31 December 2018. Archived 27 December 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- Robin Lane Fox (4 October 2013). "An Alpine garden in Poland with a heavenly Devil's Lapfoot". Financial Times, Opinion Homes and Gardens. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- "Gazeta Wrocławska – Wiadomości Wrocław, Informacje Wrocław". Gazetawroclawska.pl. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Stopka redakcyjna". Kaufland (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- nwalejac (1 October 2013). "The Wrocław Research Centre EIT+". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "DHL Express zbudował nową bazę logistyczną pod Wrocławiem". www.tuwroclaw.com (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Powstaje największe centrum handlowe w Polsce". Onet Biznes. 28 June 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- pan (20 March 2013). "Qatar Airways expands in Poland with new European Customer Contact Centre". TTG MENA. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Credit Suisse opens Centre of Excellence in Wrocław". 5 March 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- "IBM Opens Service Delivery Center in Wrocław". 13 September 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- "Microsoft opens software development centre in Wrocław". 30 September 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- "Najwięcej pasażerów w 2018 roku skorzystało z dworca Wrocław Główny". www.rynek-kolejowy.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Home page" (in Polish). Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "Gdzie jesteśmy - PANEK CarSharing | Auto na Minuty". panekcs.pl. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Nowy wypożyczalnia aut hybrydowych we Wrocławiu". www.wroclaw.pl.

- "Polinka - Wrocław University of Science and Technology". pwr.edu.pl. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Sprawozdanie z III Ogólnopolskiego Zjazdu Rodzimowierców – Rodzima Wiara – oficjalna strona". Rodzimawiara.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Polska, Grupa Wirtualna. "Tak świętują Dziady. Tajemniczy obrzęd polskich pogan". sfora.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Polish city marks first rabbinic ordination since World War II, The Times of Israel, 3 September 2014

- Fitch Rating Report on Wrocław dated July 2008, p.3

- "Strona główna – Uniwersytet Wrocławski". Uni.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Ranking Szkół Wyższych tygodnika WPROST". Szkoly.wprost.pl. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- "Politechnika Wrocławska". Pwr.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Ranking Szkół Wyższych tygodnika WPROST". Szkoly.wprost.pl. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- "Uniwersytet Medyczny im. Piastów Śląskich we Wrocławiu". Umed.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego we Wrocławiu". Awf.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu – Najlepsze studia ekonomiczne". Ae.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Ranking Szkół Wyższych tygodnika WPROST". Szkoly.wprost.pl. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- "Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu". Up.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Ranking Szkół Wyższych tygodnika WPROST". Szkoly.wprost.pl. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- "Akademia Sztuk Pięknych we Wrocławiu". Asp.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Akademia Muzyczna --". Amuz.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Teatralna im. Ludwika Solskiego w Krakowie Filia we Wrocławiu". Pwst.wroc.pl. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Uczelnia". Wso.wroc.pl. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Studia Prawo". Wyższa Szkoła Prawa (in Polish). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Wrocław hailed European Best Destination 2018!". VisitWroclaw.eu. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Paull, John (2011). "Attending the First Organic Agriculture Course: Rudolf Steiner's Agriculture Course at Koberwitz, 1924". European Journal of Social Sciences. 21 (1): 64–70.

- Redakcja (25 April 2020). "Remont Piwnicy Świdnickiej we Wrocławiu dobiega końca. Kiedy otwarcie?". Wrocław Nasze Miasto (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "10 things to do in Wroclaw". The Independent. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Iwona Gołaj, Grzegorz Wojturski (2006). "The National Museum in Wrocław. History". Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu. Przewodnik (in Polish and English). Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- "Microcosm: a Portrait of a Central European City. | Norman Davies official website". www.normandavies.com. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Following the footsteps of Eberhard Mock". VisitWroclaw.eu. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Pixelirium.pl. "Wrocław becomes UNESCO City of Literature!". Wrocławski Dom Literatury (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "wroclawmaraton.pl". wroclawmaraton.pl. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Miasta partnerskie". visitwroclaw.eu (in Polish). Wrocław. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "Lei Ordinária 1629 2006 de Araucária PR". leismunicipais.com.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Batumi miastem partnerskim Wrocławia". www.wroclaw.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Wysocki, Tomasz. "Oxford miastem partnerskim Wrocławia". www.wroclaw.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Miasta partnerskie - Biuletyn Informacji Publicznej Urzędu Miejskiego Wrocławia". bip.um.wroc.pl. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

Bibliography

English language

- Davies, Norman; Roger Moorhouse (2002). Microcosm: Portrait of a Central European City. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-06243-5.

- Till van Rahden, Jews and Other Germans: Civil Society, Religious Diversity, and Urban Politics in Breslau, 1860–1925 (2008. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press

- Gregor Thum, Uprooted. How Breslau Became Wrocław During the Century of Expulsions (2011. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Strauchold, Grzegorz; Eysymontt, Rafał (2016). Wrocław/Breslau. Historical-Topographical Atlas of Silesian Towns. Volume 5. Translated by Connor, William. Marburg: Herder Institute for Historical Research on East Central Europe. ISBN 978-3-87969-411-2.

Polish language

- Harasimowicz, Jan; Suleja, Włodzimierz (2006). Encyklopedia Wrocławia. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. ISBN 978-83-7384-561-9.

- Kulak, Teresa (2006). Wrocław. Przewodnik historyczny (A to Polska właśnie). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. ISBN 978-83-7384-472-8.

- Gregor Thum, Obce miasto: Wrocław 1945 i potem, Wrocław: Via Nova, 2006

German language

- Scheuermann, Gerhard (1994). Das Breslau-Lexikon (2 vols.). Dülmen: Laumann n. BidVerlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-89960-132-9.

- van Rahden, Till (2000). Judenbiskupln nund andere Breslauer: Die Beziehungen zwischen Juden, Protestanten und Katholiken in einer deutschen Großstadt von 1860 bis 1925. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-35732-3.

- Thum, Gregor (2002). Die fremde Stadt: Breslau 1945. Berlin: Siedler. ISBN 978-3-88680-795-6.

- Weczerka, Hugo (2003). Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-520-31602-8.

External links

- Municipal website (in Polish, English, and French)

- Tourist Information Centre website (in Polish and English)

- MPK Wrocław (transport company website) (in Polish)

- Christmas market (in Polish and English)

- Wrocław in tripadvisor

.jpg)