Matera

Matera (Italian pronunciation: [maˈtɛːra], locally [maˈteːra] (![]()

Matera | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Matera | |

Panorama of Matera | |

Coat of arms | |

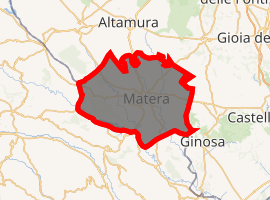

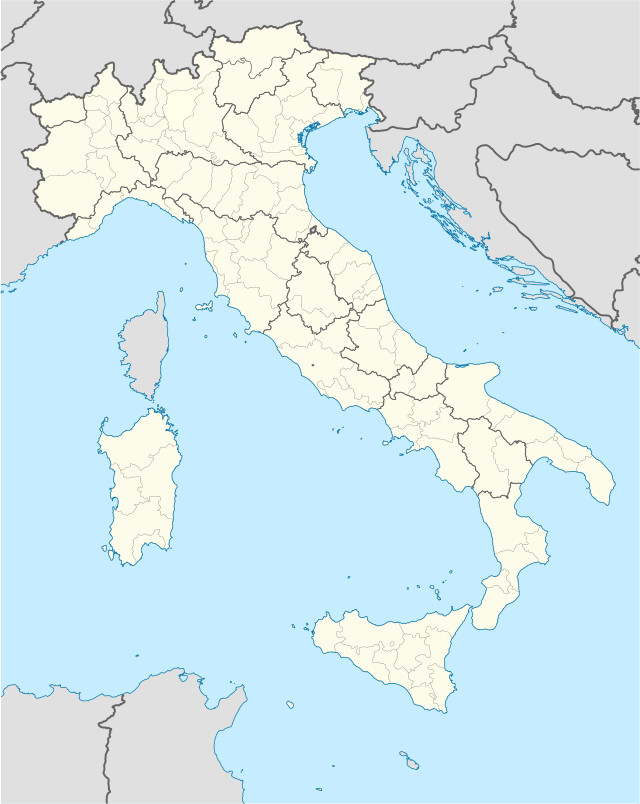

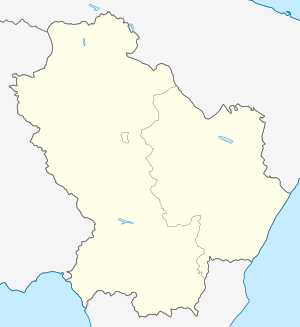

.svg.png) Matera within the Province of Matera | |

Location of Matera

| |

Matera Location of Matera in Basilicata  Matera Matera (Basilicata) | |

| Coordinates: 40°40′N 16°36′E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Basilicata |

| Province | Matera (MT) |

| Frazioni | La Martella, Venusio, Picciano A, Picciano B |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Raffaello De Ruggieri |

| Area | |

| • Total | 387.4 km2 (149.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 401 m (1,316 ft) |

| Population (January 1, 2018)[2] | |

| • Total | 60,403 |

| • Density | 160/km2 (400/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Materani |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 75100 |

| Dialing code | 0835 |

| Patron saint | Madonna della Bruna |

| Saint day | July 2 |

| Website | Official website |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Sassi of Matera | |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv, v |

| Reference | 670 |

| Inscription | 1993 (17th session) |

| Area | 1,016 ha |

| Buffer zone | 4,365 ha |

As the capital of the province of Matera, its original settlement lies in two canyons carved by the Gravina River. This area, the Sassi di Matera, is a complex of cave dwellings carved into the ancient river canyon, often cited as "one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world."[3] Over the course of its history, Matera has been occupied by Greeks, Romans, Longobards, Byzantines, Saracens, Swabians, Angevins, Aragonese, and Bourbons.[3]

By the late 1800s, Matera's cave dwellings became noted for intractable poverty, poor sanitation, meager working conditions, and rampant disease. Evacuated in 1952, the population was relocated to modern housing, and the Sassi (Italian for "stones") lay abandoned until the 1980s. Renewed vision and investment led to the cave dwellings becoming a noted historic tourism destination, with hotels, small museums and restaurants – and a vibrant arts community.

Known as la città sotterranea ("the underground city"), the Sassi and the park of the Rupestrian Churches were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. In 2019, Matera was declared a European Capital of Culture.

History

Though scholars continue to debate the date the dwellings were first occupied in Matera, and the continuity of their subsequent occupation, the area of what is now Matera is believed to have been settled since the Palaeolithic (10th millennium BC). This makes it potentially one of the oldest continually inhabited settlements in the world.[4] Alternatively it has been suggested by architectural historian Anne Parmly Toxey that the area has been "occupied continuously for at least three millennia and occupied sporadically for 150–700 millennia prior to this".[5]

The town of Matera was founded by the Roman Lucius Caecilius Metellus in 251 BC who called it Matheola.[6] In AD 664 Matera was conquered by the Lombards and became part of the Duchy of Benevento. Architectural historian Anne Parmly Toxey writes that "The date of Matera's founding is debated; however, the revered work of the city’s early chroniclers provides numerous, generally accepted accounts of Goth, Longobard, Byzantine, and Saracen sieges of the city beginning in the eighth century and accelerating through the ninth century CE."[7] In the 7th and 8th centuries the nearby grottos were colonised by both Benedictine and Basilian monastic institutions. The 9th and 10th centuries were characterised by the struggle between the Byzantines and the German emperors, including Louis II, who partially destroyed the city. After the settlement of the Normans in Apulia, Matera was ruled by William Iron-Arm from 1043.

After a short communal phase and a series of pestilences and earthquakes, the city became an Aragonese possession in the 15th century, and was given in fief to the barons of the Tramontano family. In 1514, however, the population rebelled against the oppression and killed Count Giovanni Carlo Tramontano. In the 17th century Matera was handed over to the Orsini and then became part of the Terra d'Otranto, in Apulia. Later it was capital of the province of Basilicata, a position it retained until 1806, when Joseph Bonaparte assigned it to Potenza.

In 1927 it became capital of the new province of Matera.

Government

Main sights

The Sassi (ancient town)

Matera has gained international fame for its ancient town, the "Sassi di Matera". The Sassi originated in a prehistoric troglodyte settlement, and these dwellings are thought to be among the first ever human settlements in what is now Italy. The Sassi are habitations dug into the calcareous rock itself, which is characteristic of Basilicata and Apulia. Many of them are really little more than small caverns, and in some parts of the Sassi a street lies on top of another group of dwellings. The ancient town grew up on one slope of the rocky ravine created by a river that is now a small stream, and this ravine is known locally as "la Gravina". In the 1950s, as part of a policy to clear the extreme poverty of the Sassi, the government of Italy used force to relocate most of the population of the Sassi to new public housing in the developing modern city.

Until the late 1980s the Sassi was still considered an area of poverty, since its dwellings were, and in most cases still are, uninhabitable and dangerous. The present local administration, however, has become more tourism-orientated, and it has promoted the regeneration of the Sassi as a picturesque touristic attraction with the aid of the Italian government, UNESCO, and Hollywood. Today there are many thriving businesses, pubs and hotels there, and the city is amongst the fastest growing in southern Italy.

Interior of a cave house

Interior of a cave house

.jpg)

Exterior of a cave church

Exterior of a cave church Interior of a cave church

Interior of a cave church

Monasteries and churches

Matera preserves a large and diverse collection of buildings related to the Christian faith, including a large number of rupestrian churches carved from the calcarenite rock of the region.[8] These churches, which are also found in the neighbouring region of Apulia, were listed in the 1998 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund.

Matera Cathedral (1268–1270) has been dedicated to Santa Maria della Bruna since 1389. Built in an Apulian Romanesque architectural style, the church has a 52 m tall bell tower, and next to the main gate is a statue of the Maria della Bruna, backed by those of Saints Peter and Paul. The main feature of the façade is the rose window, divided by sixteen small columns. The interior is on the Latin cross plan, with a nave and two aisles. The decoration is mainly from the 18th century Baroque restoration, but recently a Byzantine-style 14th-century fresco portraying the Last Judgement has been discovered.

Two other important churches in Matera, both dedicated to the Apostle Peter, are San Pietro Caveoso (in the Sasso Caveoso) and San Pietro Barisano (in the Sasso Barisano). San Pietro Barisano was recently restored in a project by the World Monuments Fund, funded by American Express. The main altar and the interior frescoes were cleaned, and missing pieces of moldings, reliefs, and other adornments were reconstructed from photographic archives or surrounding fragments.[9]

There are many other churches and monasteries dating back throughout the history of the Christian church. Some are simple caves with a single altar and maybe a fresco, often located on the opposite side of the ravine. Some are complex cave networks with large underground chambers, thought to have been used for meditation by the rupestrian and cenobitic monks.

Cisterns and water collection

Matera was built above a deep ravine called Gravina of Matera that divides the territory into two areas. Matera was built such that it is hidden, but made it difficult to provide a water supply to its inhabitants. Early dwellers invested tremendous energy in building cisterns and systems of water channels.

The largest cistern has been found under Piazza Vittorio Veneto. With its solid pillars carved from the rock and a vault height of more than fifteen metres, it is a veritable water cathedral, which is navigable by boat. Like other cisterns in the town, it collected rainwater that was filtered and flowed in a controlled way to the Sassi.

There were also a large number of little superficial canals (rasole) that fed pools and hanging gardens. Moreover, many bell-shaped cisterns in dug houses were filled up by seepage. Later, when the population increased, many of these cisterns were turned into houses and other kinds of water-harvesting systems were realised.

Some of these more recent facilities have the shape of houses submerged in the earth.[10]

Other sights

The Tramontano Castle, begun in the early 16th century by Gian Carlo Tramontano, Count of Matera, is probably the only other structure that is above ground of any great significance outside the sassi. However, the construction remained unfinished after his assassination in the popular riot of 29 December 1514. It has three large towers, while twelve were probably included in the original design. During some restoration work in the main square of the town, workers came across what were believed to be the main footings of another castle tower. However, on further excavation large Roman cisterns were unearthed. Whole house structures were discovered where one can see how the people of that era lived.

The Palazzo dell'Annunziata is a historical building on the main square, seat of Provincial Library.

Culture

On 17 October 2014, Matera was declared European Capital of Culture for 2019, together with Bulgaria's second-largest city, Plovdiv.

Cuisine

The crapiata is an old recipe hailing from Matera dating to the Roman period. It is a common ritual grown into "Sassi di Matera" and celebrated on 1 August; it is still celebrated. The crapiata is a simple dish of water, chickpeas, beans, wheat, lentils, potatoes and salt.

Matera's bread is a local bread made with durum wheat, dating to the Kingdom of Naples, and typically featuring three incisions, symbolizing the Holy Trinity.

Matera's inhabitants, as the tradition says, during the Carnival were used to eat the meat of the sheep that could not longer be used to produce milk or wool. The owner of the sheep, already dead, put it on a table and took away its coat. Later the meat was cut and so ready to be cooked. Because the sheep weighed about 8–10 kg., when they cooked it they invited all the neighbours and they enjoyed dance, music and wine. The meal was called pignata (in dialect:"La pignèt") after its terracotta pot shaped like an amphora. In the pot with the sheep meat there were other food like shelled and cut potatoes("U patèn sczzlèt i tagghièt"), cut or even whole onion ("La cjpaud"), tomatoes in pieces ("‘U pmmdaur"), celery ("L’occij") and salt ("‘U sèl"). The container was closed with a wheat dough before being placed on low fire powered with the charcoal. The cooking lasted about 3–4 hours and then the meat could be eaten with cheese.

Cinema

Because of the ancient primeval-looking scenery in and around the Sassi, it has been used by filmmakers as the setting for ancient Jerusalem. The following famous biblical period motion pictures were filmed in Matera:

- Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964)

- Bruce Beresford's King David (1985)

- Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ (2004)

- Abel Ferrara's Mary (2005)

- Catherine Hardwicke's The Nativity Story (2006)

- Cyrus Nowrasteh's The Young Messiah (2016)

- Timur Bekmambetov's Ben-Hur (2016)

- Garth Davis's Mary Magdalene (2018)

Other movies filmed in the city include:

- Mario Volpe's Le due sorelle (1950)

- Alberto Lattuada's La lupa (1953)

- Roberto Rossellini's Garibaldi (1961)

- Luigi Zampa's Roaring Years (1962)

- Brunello Rondi's Il demonio (1963)

- Nanni Loy's Made in Italy (1965)

- Francesco Rosi's More Than a Miracle (1967)

- Lucio Fulci's Don't Torture a Duckling (1972)

- Roberto Rossellini's Anno uno (1974)

- Paolo and Vittorio Taviani's Allonsanfàn (1974)

- Fernando Arrabal's The Tree of Guernica (1975)

- Carlo Di Palma's Qui comincia l'avventura (1975)

- Francesco Rosi's Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979)

- Francesco Rosi's Three Brothers (1981)

- Paolo and Vittorio Taviani's The Sun Also Shines at Night (1990)

- Giuseppe Tornatore's The Star Maker (1995)

- John Moore's The Omen (2006)

- Liu Jiang's Let's Get Married (2015)

- Matteo Rovere's Italian Race (2016)

- Patty Jenkins's Wonder Woman (2017)

- Cary Joji Fukunaga's No Time to Die (2020)

Music

Matera appears in the music videos for the songs "Sun Goes Down" (2014) by Robin Schulz[11] and "Spit Out the Bone" (2016) by Metallica.[12]

Religious traditions

The origins of the festival are not well known, because its story has changed while being handed down from generation to generation. One of these legends says that a women asked a farmer to go up on his wagon to accompany her to Matera. When she arrived to the periphery of the city, she got off the wagon and asked farmer to bring an her message to bishop. In this message she said she was Christ's mother. The bishop, the clergy and the folk rusched to receive the Virgin, but they found a statue. So the statue of Madonna entered in the city on a triumphal wagon. Another legend talks about a destruction of the wagon: Saracens besiege Matera and the citizens to protect the painting of Madonna, hit it on a little wagon. then they destroyed the wagon to not let the Saracens take the painting.[13]

Different hypotheses are attributed to the name of Madonna della Bruna : the first one says that the noun derives from the Lombard high-medieval term brùnja (armor/protection of knights). So the name mean Madonna of defense. Another hypothese supports that the name comes from herbon, a city of Guinea, where the Virgin went to visit her cousin Elisabetta. The last hypotese says that the name comes from the colour of the Virgin's face. The profane insertions as the navalis wagon and its violent destruction, with the intimacy and the religious solemnity, make this festival an interesting event that sinks its roots in the ancient representations that happened in a lot of mediterranean's countries. For example, in Greek culture celebrating also wedding parties through tiumphal wagon (ships on wheels richly designed) was recurring.[14] The Madonna's sculpture is located into a case in the trasept of the cathedral, dedicated to her. Here there is also a fresco that portrays her. It dates back to the 13th century and it belongs to the Byzantine school.[15]

Notable people

- Luigi De Canio (1957), football manager

- Egidio Romualdo Duni (1708–1775), composer

- Emanuele Gaudiano (1986), show jumping rider

- Cosimo Fusco (1962), actor

- John of Matera (1070–1139), Benedictine monk and saint

- Enzo Masiello (1969), Paralympic athlete

- Antonio Persio (1542–1612), philosopher

- Tommaso Stigliani (1573–1651), poet and writer

- Giovanni Carlo Tramontano (1451–1514), nobleman

Transportation

Matera is the terminal station of the Bari-Matera, a narrow gauge railroad managed by Ferrovie Appulo Lucane. The nearest airport is Bari Airport. Matera is connected to the A14 Bologna-Taranto motorway through the SS99 national road. It is also served by the SS407, SS665 and SS106 national road.

Bus connection to Italy's main cities is provided by private firms.

Sports

- Football Club Matera

- Olimpia Matera, a basketball team

Gallery

Via Ridola

Via Ridola Via Bruno Buozzi

Via Bruno Buozzi Chiesa di San Francesco d'Assisi

Chiesa di San Francesco d'Assisi- Church of San Agostino

- Church of San Giovanni Battista

San Pietro Caveoso

San Pietro Caveoso

See also

- Church of San Leonardo (Matera)

- Matera Centrale railway station

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- "Total Resident Population on 1st January 2018 by sex and marital status. Municipality: Matera". National Institute of Statistics (Italy). Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- D. T. Max (April 20, 2015). "Cave With a View". The New Yorker.

- Leonardo A. Chisena, Matera dalla civita al piano: stratificazione, classi sociali e costume politico, Congedo, 1984, p.7

- Anne Parmly Toxey (2016). "Recasting Materan Identity: The Warring And Melding Of Political Ideologies Carved In Stone". In Micara, Ludovico; Petruccioli, Attilio; Vadini, Ettore (eds.). The Mediterranean Medina: International Seminar. Gangemi Editore spa. ISBN 9788849290134. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Domenico, Roy Palmer (2002). The Regions of Italy: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 37. ISBN 9780313307331.

- Toxey, Anne Parmly (2013). Materan Contradictions: Architecture, Preservation and Politics. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 36. ISBN 9781409482666. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Colin Amery and Brian Curran, Vanishing Histories, Harry N. Abrams, New York, NY: 2001, p. 44.

- World Monuments Fund – Rupestrian Churches of Puglia and the City of Matera

- Museo Laboratorio della Civiltà Contadina ONLUS (2014) [1st. Pub. 2007]. Water-harvesting systems of Matera, from Neolithic to the first half of XX century. Matera. ISBN 1500611565.

- Lilja Haefele (October 6, 2014). "Robin Schulz "Sun Goes Down" (Lilja, dir.)". videostatic.com. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- "Matera nel nuovo video dei Metallica". retecinemabasilicata.it. November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- Rota, Lorenzo (2001). Matera : the History of a Town. Matera: Giannatelli. p. 342. ISBN 9788897906001.

- "The Feast of the Madonna della Bruna". Festa della Bruna. 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- Morelli, Michele (2006). La festa della Bruna. Matera: Adecom. ISBN 9788897906001.

Other sources

- Giura Longo, Raffaele (1970). Sassi e secoli. Matera: BMG.

External links

- Travel Video promotion APT Basilicata (in English)

- UNESCO site

- Museo Laboratorio della Civiltà Contadina

- BBC News: Italian cave city goes hi-tech