Potsdam Conference

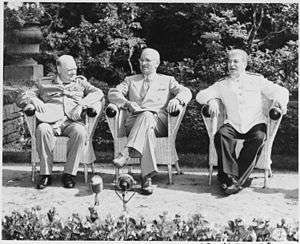

The Potsdam Conference (German: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held in Potsdam, Germany, from 17 July to 2 August 1945. (In some older documents, it is also referred to as the Berlin Conference of the Three Heads of Government of the USSR, the USA, and the UK.[2][3]) The participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States, represented respectively by Premier Joseph Stalin, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill[4] and Clement Attlee,[5] and President Harry S. Truman.

| Potsdam Conference | |

|---|---|

The "Big Three" at the Potsdam Conference, Winston Churchill, Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin. | |

| Host country | |

| Date | 17 July – 2 August 1945 |

| Venue(s) | Cecilienhof |

| Cities | Potsdam, Germany |

| Participants | |

| Follows | Yalta Conference |

They gathered to decide how to administer Germany, which had agreed to unconditional surrender nine weeks earlier on the 8th of May (Victory in Europe Day).[6] The goals of the conference also included the establishment of postwar order, peace treaty issues, and countering the effects of the war.

Additionally, the Foreign Secretaries of the three Governments, James F. Byrnes, V. M. Molotov, and Anthony Eden, the Chief of Staff, with other advisers also participated in the Conference. From July 17 to July 25 there were held nine meetings. After that, the Conference was interrupted for two days, as the results of the British general election were being announced. On July 28, Prime Minister Clement Attlee defeated Winston Churchill in the British general election and replaced him as Britain’s representative through the Potsdam Conference, accompanied by the new Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Ernest Bevin. Four days of further discussion followed. During the Conference there were steady meetings of the heads of the three Governments along with the Foreign Secretaries, and also of the Foreign Secretaries alone. Committees that were appointed by the latter ones for precursory consideration of questions before the Conference also met daily. Important decisions and agreements were reached and views were exchanged on a plethora of other questions. However, consideration of these matters was continued by the Council of Foreign Ministers established by the Conference subsequently. The Potsdam Conference ended having strengthened the relationship between the three Governments in view of their collaboration, with renewed confidence that together with the other United Nations they would insure the creation of a just and enduring peace.[7][8]

Relationships among the leaders

A number of changes had taken place in the five months since the Yalta Conference that greatly affected the relationships among the leaders. The Soviet Union had occupied Central and Eastern Europe, and the Red Army effectively controlled the Baltic states, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania, and refugees were fleeing from those countries. Stalin had set up a puppet communist government in Poland, insisted that his control of Eastern Europe was a defensive measure against possible future attacks and claimed that it was a legitimate sphere of Soviet influence.[9]

Also, Britain had a new prime minister. Conservative Party leader Winston Churchill had served as prime minister in a coalition government; his Soviet policy, since the early 1940s, had differed considerably from Roosevelt's; Churchill believed Stalin to be a "devil"-like tyrant who led a vile system.[10] A general election had been held in the UK on 5 July 1945, but the results were delayed to allow the votes of armed forces personnel to be counted in their home constituencies. The outcome became known during the conference, when Labour leader Clement Attlee became the new prime minister.

Then, Roosevelt had died on 12 April 1945, and Vice-President Harry Truman assumed the presidency; his succession saw VE Day (Victory in Europe) within a month and VJ Day (Victory in Japan) on the horizon. During the war and in the name of Allied unity, Roosevelt had brushed off warnings of a potential domination by Stalin in part of Europe, explaining, "I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of a man.... I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask for nothing from him in return, 'noblesse oblige', he won't try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace".[11]

Truman had closely followed the Allied progress of the war. George Lenczowski noted that "despite the contrast between his relatively modest background and the international glamour of his aristocratic predecessor, [Truman] had the courage and resolution to reverse the policy that appeared to him naive and dangerous", which was "in contrast to the immediate, often ad hoc moves and solutions dictated by the demands of the war".[12] With the end of the war, the priority of Allied unity was replaced with the challenge of the relationship between the two emerging superpowers.[12] Both leading powers continued to sustain a cordial relationship to the public, but suspicions and distrust lingered between them.[13]

Truman was much more suspicious of the communists than Roosevelt had been, and he became increasingly suspicious of Soviet intentions under Stalin.[12] He and his advisers saw Soviet actions in Eastern Europe as aggressive expansionism that was incompatible with the agreements that Stalin had committed to at Yalta the previous February. In addition, Truman became aware of possible complications elsewhere when Stalin objected to Churchill's proposal for an early Allied withdrawal from Iran, ahead of the schedule agreed at the Tehran Conference. The Potsdam Conference was the only time that Truman met Stalin in person.[14][15]

At the Yalta Conference, France had been granted an occupation zone within Germany. France had been a participant in the Berlin Declaration and was to be an equal member of the Allied Control Council. Nevertheless, at the insistence of the Americans, Charles de Gaulle was not invited to Potsdam, just as he had been denied representation at Yalta. The diplomatic slight was a cause of deep and lasting resentment for him.[16] Reasons for the omissions included the longstanding personal mutual antagonism between Roosevelt and De Gaulle, ongoing disputes over the French and American occupation zones and anticipated conflicts of interest over French Indochina,[17] but it also reflected the judgement of both the British and Americans that French aims in respect of many items on the conference's agenda were likely to contradict the Anglo-American agreed objectives.[18]

Agreements

Potsdam Agreements

At the end of the conference, the three heads of government agreed on the following actions. All other issues were to be answered by the final peace conference, which was to be called as soon as possible.

Germany

- The Allies issued a statement of aims of their occupation of Germany: demilitarization, denazification, democratization, decentralization, dismantling and decartelization. More specifically, as for the demilitarization and disarmament of Germany the Allies decided to abolish the SS, SA, SD, and Gestapo, all the air, land, and naval forces as well as all the organizations, staffs, and institutions which were in charge of keeping alive the military tradition in Germany. Concerning the democratization of Germany, the "Big Three" thought that it was of great importance for the Nazi Party and its affiliated organizations to be destroyed. Thus, the Allies would prevent all Nazi activity and prepare for the reconstruction of the German political life as a democratic state.[19]

- It was also decided that all the Nazi laws would be abolished. These laws established discrimination on grounds of race, creed and political opinion and as a result could not be accepted in a democratic country.[20]

- Germany and Austria were both to be divided into four occupation zones, as had been agreed in principle at Yalta, and similarly each capital (Berlin and Vienna) was to be divided into four zones.

- Nazi war criminals were to be put on trial. Specifically, at the Potsdam Conference, the three governments tried to reach an agreement on the trial methods of the Nazi war criminals, whose crimes during the World War 2 under the Moscow Declaration of October 1943 had no geographical restriction. At the same time, the leaders were aware of the discussions, which were continuing for weeks in London between the representatives of the United States, United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union. Their purpose was to lead these war criminals to trial as soon as possible and eventually to justice. The first list of defendants would be published before September 1. The leaders’ main wish was that the London negotiations would have a positive result validated by an agreement (it was signed at London on August 8 1945).[21]

- All German annexations in Europe were to be reversed, including Sudetenland, Alsace-Lorraine, Austria, and the westernmost parts of Poland.

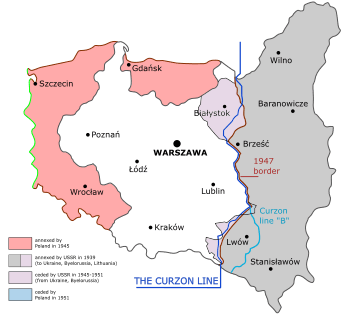

- Germany's eastern border was to be shifted westwards to the Oder–Neisse line, effectively reducing Germany in size by approximately 25% from its 1937 borders. The territories east of the new border were East Prussia, Silesia, West Prussia and two thirds of Pomerania. Those areas were mainly agricultural, with the exception of Upper Silesia, which was the second-largest centre of German heavy industry.

- "Orderly and humane" expulsions of the German populations remaining beyond the new eastern borders of Germany were to be carried out from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, but not Yugoslavia.[22]

- Nazi party members, who had positions of responsibility in public and were against of the Allied purposes, were removed from the public and semipublic office. They were replaced by people who based on their political and moral beliefs were supporting the democratic system.[23]

- The judicial system was reorganized based on democratic ideas of equality and justice under law.[24]

- The educational system of Germany was controlled by the Allies, in order for it to replace the fascistic ideas with democratic ones.[25]

- Allies encouraged the existence of democratic parties with rights of assembly and of public discussions in Germany.[26]

- The freedom of speech, press, religion and religious institutions, as well as the formation of free trade unions were all permitted by the Allies.[27]

- War reparations to the Soviet Union from its zone of occupation (eastern zone) in Germany were agreed. In addition to these reparations, the Soviet Union should also receive an amount of reparations from the western zones of occupation, but had to give up all claims referring to the German industries located in the western zones of occupation in Germany. Specifically, 15% of usable industrial capital equipment, consisted of metallurgical, chemical and machine manufacturing industries should be removed from the western zones, in exchange of food, coal, potash, zinc, timber, clay and petroleum products from the eastern zones.The Soviet Union had the responsibility to transfer the products from the eastern zone within five years. Moreover, 10% of the industrial capacity of the western zones unnecessary for the German peace economy should be transferred to the Soviet Union within two years, as reparation’s account without the obligation of any further exchanges of kind in return. The Soviet Union promised to settle the reparation claims of Poland from its own share of reparations.[28] Stalin proposed, which was accepted, for Poland was to be excluded from division of German compensation and to be later granted 15% of compensation given to the Soviet Union.[8][29] At the end of the discuss, the Soviet Union did not make any claims about the gold captured by the troops in Germany.[30]

- Primarily, the Conference concluded that it was necessary to set boundaries regarding the use and disposition of the defeated German navy and merchant ships. The American, British and Soviet Union's governments reached the decision that they would assign to experts to cooperate, in order to organise well-defined plans, which would lead to the agreed principles. This would be also publicly announced at the same time by the three Governments at a short-term period.[31]

- War reparations to the United States, United Kingdom and other countries should be received from their own zones of occupation (western zones) and the amount of reparations removed from the western zones should be determined within six months. They had to give up all their claims referring to the German industries located in the eastern zone of occupation, as well as to German foreign assets in Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary, Romania and Eastern Austria. The removal of the industrial equipment on their own zones should begin soon and be completed within two years from the determination of reparations. At the end, the Control Council should make the determination of the equipment following the policies by the Allied Commission with the participation of France.[8][32]

- German standards of living were to be ensured to prevent them from exceeding the European average. The types and amounts of industry to dismantle to achieve that was to be determined later (see Allied plans for German industry after World War II).

- German industrial war potential was to be destroyed by the destruction or control of all industry with military potential. To that end, all civilian shipyards and aircraft factories were to be dismantled or otherwise destroyed. All production capacity associated with war potential, such as metals, chemical or machinery, were to be reduced to a minimum level, which would later be determined by the Allied Control Commission. Manufacturing capacity thus made "surplus" was to be dismantled as reparations or otherwise destroyed. All research and international trade was to be controlled. The economy was to be decentralised (decartelisation). The economy was also to be reorganised, with the primary emphasis on agriculture and peaceful domestic industries. In early 1946, agreement was reached on the details of the latter: Germany was to be converted into an agricultural and light industrial economy. German exports were to be coal, beer, toys, textiles, etc., which would take the place of the heavy industrial products, which had formed most of Germany's prewar exports.[33]

France, having been excluded from the conference, resisted implementing the Potsdam agreements within its occupation zone. In particular, the French refused to resettle any expelled Germans from the east. Moreover, the French did not accept any obligation to abide by the agreements in the proceedings of the Allied Control Council; in particular, they resisted all proposals to establish common policies and institutions across Germany as a whole and anything that they feared could lead to the emergence of an eventual unified German government.[34]

Poland

- A Provisional Government of National Unity, recognized by all three powers, should be created, known as the Lublin Poles. The Big Three's recognition of the Soviet-controlled government effectivity meant the end of recognition of the existing Polish government-in-exile, known as the London Poles.

- The British and United States Governments took measures in order for the Polish Provisional Government to be the owner of the property located in the territories of Poland. Polish Provisional Government had all the legal rights in this property and no other government could conquer it .[35]

- Poles who were serving in the British Army should be free to return to Poland, with no security upon their return to the communist country guaranteed.

- The Allies decided that all Poles who would return to Poland would also be accorded personal and property rights.[36]

- The Polish Provisional Government agreed to hold, as soon as possible, free elections based on suffage and secret ballot. All the democratic and anti-Nazi parties could take part in these elections and the reprsentatives of the Allied press would inform the world about the results .[37]

- The provisional western border should be the Oder–Neisse line, defined by the Oder and Neisse Rivers. Silesia, Pomerania, the southern part of East Prussia and the former Free City of Danzig should be under Polish administration. However, the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement, which would take place 45 years later, at the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany in 1990.[8]

- The Soviet Union declared that it would settle the reparation claims of Poland from its own share of the overall reparation payments.[8][38]

Austria

Soviet Government proposed the extension of the authority of the Austrian Provisional Government and the Allies agreed to examine the proposal after the entry of the British and American forces in Vienna.[39]

Prussia

The Soviet Government proposed to the Conference that the suspense of territorial questions should be resolved permanently, after the peace was settled down at those regions. More specifically, the proposal referred to the section of the western frontier of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics which was located near to the Baltic Sea. This area should pass on the eastern shore of the Bay of Danzig to the east, north of Braunsberg and Goldap, to the meeting point of the frontiers of Lithuania, the Polish Republic and East Prussia.

Finally, after the Conference considered thoroughly the recommendation of the Soviet Union, it was agreed that the entire city of Koenigsburg and the area next to it should be transferred, as described previously, to the Soviet Union.

The President Harry S. Truman and Prime Minister Winston Churchill had guaranteed that they would support the proposal of the Conference, when the peace was eventually ensured.[40]

Italy

The Soviet Union made another proposal to the conference concerning the mandated territories as it was decided in the Crimea Conference and in the Charter of the United Nations Organization.

After various opinions had been heard and discussed on this question, the Foreign Prime Ministers agreed that it was essential to decide at once the preparation of a peace treaty for Italy, combined with the arrangement of any former Italian territories. In September the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs would examine the question about the italian territory.[41]

Orderly Transfers of German Population

At the Conference, the leaders agreed on the removal of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. The three governments were convinced that not only the transfer of German populations, but also the elements, which were remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary should begin as soon as possible. They emphasized that the transfers should be completed in an orderly and humane manner. Firstly, at the Potsdam Conference the leaders decided that the Allied Control Council in Germany should deal with the matter giving priority to the equal distribution of Germans among the zones of occupation. They were giving advice to their representatives on the Control Council to report to their governments the number of people who had already entered Germany from the Eastern countries.[8] These representatives should also form an estimation about future transfers emphasizing to the capacity of Germany. The governments of eastern countries were being informed of the methods of further transfers and they were requested to suspend the expulsions of people. The Big Three were concerned of the reports from the Control Council and, thus, they should make an analytical examination on this matter.[42]

Revised Allied Control Commission Procedure in Rumania, Bulgaria and Hungary

The Big Three noticed that the Soviet representatives on the Allied Control Commissions in Rumania, Bulgaria and Hungary communicated to their United Kingdom and United States colleagues proposals for refining the work of the Control Commission, as the aggressions in Europe had ended. Then, the three leaders agreed on the revision of the procedures of the Allied Control Commissions in these countries, taking into consideration the interests and responsibilities of their Governments (UK, USA, and USSR), which together presented the terms of armistice to the respective countries, and accepting as a basis the agreed proposals.[8][43]

Council of Foreign Ministers

At the Conference was agreed the establishment of a Council of Foreign Ministers, that would represent the five principal powers, in order to continue the essential preliminary work for the peace settlements and to assume other matters, which could occasionally be committed to the Council, by agreement of the governments participating in the Council. The establishment of the Council in question does not go against the agreement of the Crimea conference that there should be periodic meetings among the foreign secretaries of the three Governments. According to the text of the agreement for the establishment of the Council the following were decided:[8]

- There should be established a Council composed of the Foreign Ministers of the United Kingdom, the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics, China, France and the United States.[8][44]

- (I) The Council should meet in London and form the Joint of the Secretariat. Each of the Foreign Ministers would be accompanied by a high-ranking deputy, properly authorized to continue the work of the Council in the absence of their Foreign Minister, and by a small staff of technical advisers. (II) The first meeting of the Council should be held in London not later than September 1, 1945. Meetings could also be held by common agreement in other capitals.[8][45]

- (I) The Council should be authorized to write, with a view to their submission to the United Nations, treaties of peace with Italy, Rumania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Finland, and to propose settlements of territorial issues pending on the termination of the war in Europe. The Council should also prepare a peace settlement for Germany to be accepted by the government of Germany when a government adequate for the purpose is established. (II) In order to accomplish the previous tasks, the Council would be composed of the members representing those states which were signatory to the terms of surrender imposed upon the enemy state concerned.[46]

- (I) On any occasion the Council would be considering a question of direct interest to a State not represented, such State should be requested to send representatives to participate in the discussion of that question. (II) The Council was able to adapt its procedure to the particular problem under consideration. In some cases it could hold its own initial discussions prior to the participation of other interested states. Following the decision of the Conference, the Big Three have each addressed an invitation to the Governments of China and France, in order to adopt the text and to join in establishing the Council.[8][47]

Conclusion of peace treaties and memberships to the United Nations

All in all, the Conference has concurred to apply common policy for determining, at the earliest opportunity, the terms of the peace. The statement was as follows:

In general, it was desirable by the three Governments that the problem of the abnormal position of Italy, Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary and Romania should be resolved by the end of the negotiations. They believe that the other Allies will share their point of view.

As Italy was one of the most important issues that required instant governing by the new Council of Foreign Ministers, the three Governments had drown their attention to prepare a peace treaty for this country. Italy was the first of the Axis powers, which broke the bonds with Germany and participated to the operations of the Allies against Japan.

Italy has achieved to gain her freedom and left behind the fascist regime, making a significant progress. As a result, she paved the way for the re-establishment of a democratic government. If Italy actually ended up with a recognized and democratic government, it would be much easier for the USA, Great Britain and Soviet Union to satisfy their desire and support the involvement of Italy to the United Nations.

The Council of Foreign Ministers had also the duty to examine and prepare the peace treaties for Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary and Romania.

And besides the termination of peace treaties with recognized and democratic governments in these four states would allow to the three Governments to accept the requests from them to be members of the United Nations. Moreover, after the termination of peace negotiations, the Big Three agreed to examine in the near future the restoration of the diplomatic relations among Finland, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary.

The three Governments were sure that the new situation, which was now formed in Europe after the end of the World War II, representatives of the Allied press would enjoy the freedom of expression upon developments in Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Finland.

The Article 4 of the Charter of the United Nations mentioned:

1. "Membership in the United Nations is open to all other peace-loving States who accept the obligations contained in the present Charter and, in the judgment of the organization, are able and willing to carry out these obligations;"

2. "The admission of any such state to membership in the United Nations will be effected by a decision of the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council."

The leaders declared that they were willing to support any request for membership from the states, which have remained neutral while the war was taking place, and fulfilled the requirements too.

Nevertheless, the three Governments felt the need to make clear that they were totally reluctant to support any application for membership from the Spanish Government. This is explained by the fact that Spanish Government was established with the support of the Axis powers. Consequently, due to its origins, nations and close relation to the Axis powers, the Conference was unwilling to justify the existence of such membership.[48]

Potsdam Declaration

Leahy's role

One of those at the conference is William D. Leahy. The Fleet Admiral in the US Navy had stood as advisor to Roosevelt during the Yalta Conference and to Truman during the Potsdam Conference. Leahy had a lengthy military background since he had served as the most senior American military officer on active duty during the Second World War. He later stated in his book, I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time, that the Potsdam Conference was one of the most frustrating out of all the conferences because of hostile relations between the Soviet Union and Britain and the United States. Throughout his work, he refers to the conference as its code name, Terminal. Later in his book, he discusses a tour of Berlin that he took with Truman and describes the experience as "I never saw such destruction. I don't know whether they learned anything from it or not".

In addition to the Potsdam Agreement, on 26 July, Churchill; Truman; and Chiang Kai-shek, Chairman of the Nationalist Government of China (the Soviet Union was not at war with Japan) issued the Potsdam Declaration, which outlined the terms of surrender for Japan during World War II in Asia.

Aftermath

Truman had mentioned an unspecified "powerful new weapon" to Stalin during the conference. Towards the end of the conference, on July 26, the Potsdam Declaration gave Japan an ultimatum to surrender unconditionally or meet "prompt and utter destruction", which did not mention the new bomb[49] but promised that "it was not intended to enslave Japan". The Soviet Union was not involved in that declaration since it was still neutral in the war against Japan. Japanese Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki did not respond,[50] which was interpreted as a declaration that the Empire of Japan had ignored the ultimatum.[51] As a result, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 and Nagasaki on 9 August. The justifications used were that both cities were legitimate military targets and that it was necessary to end the war swiftly and to preserve American lives.

When Truman informed Stalin of the atomic bomb, he said that the United States "had a new weapon of unusual destructive force",[52] but Stalin had full knowledge of the atomic bomb's development because of Soviet spy networks inside the Manhattan Project,[53] and he told Truman at the conference to "make good use of this new addition to the Allied arsenal".[54]

The Soviet Union converted the other countries Eastern Europe into satellite states within the Eastern Bloc, such as the People's Republic of Poland, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, the People's Republic of Hungary,[55] the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic,[56] the People's Republic of Romania[57] and the People's Republic of Albania.[58] Many of these countries had seen failed Socialist revolutions prior to World War II.

Previous major conferences

- Yalta Conference, 4 to 11 February 1945

- Second Quebec Conference, 12 to 16 September 1944

- Tehran Conference, 28 November to 1 December 1943

- Cairo Conference, 22 to 26 November 1943

- Casablanca Conference, 14 to 24 January 1943

Notes

- Description of photograph, Truman Library.

- "Avalon Project – A Decade of American Foreign Policy 1941–1949 – Potsdam Conference". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Russia (USSR) / Poland Treaty (with annexed maps) concerning the Demarcation of the Existing Soviet-Polish State Frontier in the Sector Adjoining the Baltic Sea 5 March 1957 (retrieved from the UN Delimitation Treaties Infobase, accessed on 18 March 2002)

- "Potsdam Conference". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "BBC Fact File: Potsdam Conference". Bbc.co.uk. 2 August 1945. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Attlee participated alongside Churchill while awaiting the outcome of the 1945 general election, and then replaced him as Prime Minister after the Labour Party's defeat of the Conservatives.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1224–1225.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume II - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. US State Department. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Leffler, Melvyn P., "For the South of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union and the Cold War, First Edition, (New York, 2007) pg 31

- Miscamble 2007, p. 51

- Miscamble 2007, p. 52

- George Lenczowski, American Presidents and the Middle East, (1990), pp. 7–13

- Hunt, Michael (2013). The World Transformed. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780199371020.

- Harry S. Truman, Memoirs, Vol. 1: Year of Decisions (1955), p.380, cited in Lenczowski, American Presidents, p.10

- Nash, Gary B. "The Troublesome Polish Question." The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society. New York: Pearson Longman, 2008. Print.

- Reinisch, Jessica (2013). The Perils of Peace. Oxford University Press. p. 53.

- Thomas, Martin (1998). The French Empire at War 1940-45. Manchester University Press. p. 215.

- Feis, Hebert (1960). Between War and Peace; the Potsdam Conference. Princeton University Press. pp. 138.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1227–1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1233.

- Alfred de Zayas Nemesis at Potsdam, Routledge, London 1977. See also conference on "Potsdamer Konferenz 60 Jahre danach" hosted by the Institut für Zeitgeschichte in Berlin on 19. August 2005 PDF Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Seite 37 et seq.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1228.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1231.

- "Potsdam Conference | World War II". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1232.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1232.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1231–1232.

- James Stewart Martin. All Honorable Men (1950) p. 191.

- Ziemke, Earl Frederick (1990). The US Army and the Occupation of Germany 1944–1946. Center of Military History, United States Army. p. 345.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1234.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1234.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1234.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume II - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1233.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1232–1233.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1236.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1236.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. p. 1236.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1225–1226.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1225–1226.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1225–1226.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1225–1226.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1931-1945. Department of State. pp. 1235–1236.

- "How The Potsdam Conference Shaped The Future Of Post-War Europe". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "Mokusatsu: One Word, Two Lessons" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Mokusatsu, Japan's Response to the Potsdam Declaration", Kazuo Kawai, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 19, No. 4 (November 1950), pp. 409–414.

- Putz, Catherine (18 May 2016). "What If the United States Had Told the Soviet Union About the Bomb?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Groves, Leslie (1962). Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 142–145. ISBN 0-306-70738-1. OCLC 537684.

- Nichols, Tom (12 April 2016). "Simply No Other Choice: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Japan". National Interest.org. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- Granville, Johanna, The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- Grenville 2005, pp. 370–71

- The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.

- Cook 2001, p. 17

References

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001), Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-8153-4057-5

- Crampton, R. J. (1997), Eastern Europe in the twentieth century and after, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16422-2

- Leahy, Fleet Adm William D. I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman: Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time (1950) OCLC 314294296.

- Miscamble, Wilson D. (2007), From Roosevelt to Truman: Potsdam, Hiroshima, and the Cold War, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-86244-2

- Roberts, Geoffrey (Fall 2002). "Stalin, the Pact with Nazi Germany, and the Origins of Postwar Soviet Diplomatic Historiography". Journal of Cold War Studies. 4 (4): 93–103.

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008), Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-5542-9

Further reading

- Michael Beschloss. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman, and the destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945 (Simon & Schuster, 2002) ISBN 0684810271

- Ehrman, John (1956). Grand Strategy Volume VI, October 1944-August 1945. London: HMSO (British official history). pp. 299–309.

- Farquharson, J. E. "Anglo-American Policy on German Reparations from Yalta to Potsdam." English Historical Review 1997 112(448): 904–926. in JSTOR

- Feis, Herbert. Between War and Peace: The Potsdam Conference (Princeton University Press, 1960) OCLC 259319 Pulitzer Prize; online

- Gimbel, John. "On the Implementation of the Potsdam Agreement: an Essay on U.S. Postwar German Policy." Political Science Quarterly 1972 87(2): 242–269. in JSTOR

- Gormly, James L. From Potsdam to the Cold War: Big Three Diplomacy, 1945–1947. (Scholarly Resources, 1990)

- Mee, Charles L., Jr. Meeting at Potsdam. M. Evans & Company, 1975. ISBN 0871311674

- Naimark, Norman. Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe (Harvard University Press, 2001) ISBN 0674003136

- Neiberg, Michael. Potsdam: the End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe (Basic Books, 2015) ISBN 9780465075256

- Thackrah, J. R. "Aspects of American and British Policy Towards Poland from the Yalta to the Potsdam Conferences, 1945." Polish Review 1976 21(4): 3–34. in JSTOR

- Zayas, Alfred M. de. Nemesis at Potsdam: The Anglo-Americans and the Expulsion of the Germans, Background, Execution, Consequences. Routledge, 1977. ISBN 0710004583

Primary sources

- Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers. The Conference of Berlin (Potsdam Conference, 1945) 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Potsdam Conference. |

- Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference

- Truman and the Potsdam Conference

- Annotated bibliography for the Potsdam Conference from the Alsos Digital Library

- The Potsdam Conference, July – August 1945 on navy.mil

- United States Department of State Foreign relations of the United States : diplomatic papers : the Conference of Berlin (the Potsdam Conference) 1945 Volume I Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1945

- United States Department of State Foreign relations of the United States : diplomatic papers : the Conference of Berlin (the Potsdam Conference) 1945 Volume II Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1945

- European Advisory Commission, Austria, Germany Foreign relations of the United States : diplomatic papers, 1945.

- Harry Truman Revisionist Analysis of Potsdam Conference Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Cornerstone of Steel, Time magazine, 21 January 1946

- Cost of Defeat, Time magazine, 8 April 1946

- Pas de Pagaille! Time magazine, 28 July 1947

- Interview with James W. Riddleberger Chief, Division of Central European Affairs, U.S. Dept. of State, 1944–47

- "The Myth of Potsdam," in B. Heuser et al., eds., Myths in History (Providence, Rhode Island and Oxford: Berghahn, 1998)

- "The United States, France, and the Question of German Power, 1945–1960," in Stephen Schuker, ed., Deutschland und Frankreich vom Konflikt zur Aussöhnung: Die Gestaltung der westeuropäischen Sicherheit 1914–1963, Schriften des Historischen Kollegs, Kolloquien 46 (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2000).

- U.S. Economic Policy Towards defeated countries April 1946.

- Lebensraum

- EDSITEment's lesson Sources of Discord, 1945–1946