Rock dove

The rock dove, rock pigeon, or common pigeon (/ˈpɪdʒ.ən/ also /ˈpɪdʒ.ɪn/; Columba livia) is a member of the bird family Columbidae (doves and pigeons).[3]:624 In common usage, this bird is often simply referred to as the "pigeon".

| Rock dove | |

|---|---|

| Adult male in Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Genus: | Columba |

| Species: | C. livia |

| Binomial name | |

| Columba livia | |

| |

| approximate native range introduced non-native populations | |

The domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica, which includes about 1,000 different breeds) descended from this species. Escaped domestic pigeons have increased the populations of feral pigeons around the world.[4]

Wild rock doves are pale grey with two black bars on each wing, whereas domestic and feral pigeons vary in colour and pattern. Few differences are seen between males and females.[5] The species is generally monogamous, with two squabs (young) per brood. Both parents care for the young for a time.[6]

Habitats include various open and semi-open environments. Cliffs and rock ledges are used for roosting and breeding in the wild. Originally found wild in Europe, North Africa, and western Asia, pigeons have become established in cities around the world. The species is abundant, with an estimated population of 17 to 28 million feral and wild birds in Europe alone and up to 120 million worldwide.[1][7]

Taxonomy and naming

The rock dove was first described by Gmelin in 1789.[8] The genus name Columba is the Latin word meaning "pigeon, dove",[9] whose older etymology comes from the Ancient Greek κόλυμβος (kolumbos), "a diver", from κολυμβάω (kolumbao), "dive, plunge headlong, swim".[10] Aristophanes (Birds, 304) and others use the word κολυμβίς (kolumbis), "diver", for the name of the bird, because of its swimming motion in the air. The specific epithet is derived from the Latin livor, "bluish".[11] Its closest relative in the genus Columba is the hill pigeon, followed by the other rock pigeons: the snow, speckled, and white-collared pigeons.[3]

Since 2011, the species has been officially known as the rock pigeon by the International Ornithological Congress.[12] In common usage, this bird is still often simply referred to as the "pigeon". Pigeon chicks are called squabs.[6]

Subspecies

Twelve subspecies are recognised by Gibbs (2000); some of these may be derived from feral stock.[3]:176–179

- The European rock dove (C. l. livia), the nominate subspecies, occurs in western and southern Europe, northern Africa, and Asia to western Kazakhstan, the northern Caucasus, Georgia, Cyprus, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq.

- The Cape Verde rock dove (C. l. atlantis) (Bannerman, 1931) of Madeira, the Azores and Cape Verde is a very variable population with chequered upperparts obscuring the black wingbars, and is almost certainly derived from feral pigeons.

- The Canary Islands rock dove (C. l. canariensis) (Bannerman, 1914) of the Canary Islands is smaller and is usually darker than the nominate subspecies.

- The Senegal rock dove (C. l. gymnocyclus) (Gray, 1856) from Senegal and Guinea to Ghana, Benin and Nigeria is smaller and very much darker than nominate C. l. livia. It is almost blackish on the head, rump, and underparts with a white back and the iridescence of the nape extending onto the head.

- The Saharan rock dove (C. l. targia) (Geyr von Schweppenburg, 1916) breeds in the mountains of the Sahara east to Sudan. It is slightly smaller than the nominate form, with similar plumage, but the back is concolorous with the mantle instead of white.

- The oasis rock dove (C. l. dakhlae) (Richard Meinertzhagen, 1928) is confined to the two oases in central Egypt. It is smaller and much paler than the nominate subspecies.

- The Egyptian rock dove (C. l. schimperi) (Bonaparte, 1854) is found in the Nile Delta south to northern Sudan. It closely resembles C. l. targia, but has a distinctly paler mantle.

- The Arabian rock dove (C. l. palaestinae) (Zedlitz, 1912) occurs from Syria to Sinai and Arabia. It is slightly larger than C. l. schimperi and has darker plumage.

- The Iranian rock dove (C. l. gaddi) (Zarodney & Looudoni, 1906), breeds from Azerbaijan and Iran east to Uzbekistan is larger and paler than C. l. palaestinae with which it intergrades in the west. It also intergrades with the next subspecies to the east.

- Hume's rock dove (C. l. neglecta) (Hume, 1873), is found in the mountains of eastern Central Asia. It is similar to the nominate subspecies in size, but is darker with a stronger and more extensive iridescent sheen on the neck. It intergrades with the next race in the south.

- The Indian rock dove (C. l. intermedia) (Strickland, 1844) occurs in Sri Lanka and in India south of the Himalayan range of C. l. neglecta. It is similar to that subspecies, but darker with a less contrasting back.

- The Mongolian rock dove (C. l. nigricans) (Buturlin, 1908) in Mongolia and northern China is variable and probably derived from feral pigeons.

Description

.jpg)

The adult of the nominate subspecies of the rock dove is 29 to 37 cm (11 to 15 in) long with a 62 to 72 cm (24 to 28 in) wingspan.[13] Weight for wild or feral rock doves ranges from 238–380 g (8.4–13.4 oz), though overfed domestic and semidomestic individuals can exceed normal weights.[3][5] It has a dark bluish-grey head, neck, and chest with glossy yellowish, greenish, and reddish-purple iridescence along its neck and wing feathers. The iris is orange, red, or golden with a paler inner ring, and the bare skin round the eye is bluish-grey. The bill is grey-black with a conspicuous off-white cere, and the feet are purplish-red. Among standard measurements, the wing chord is typically around 22.3 cm (8.8 in), the tail is 9.5 to 11 cm (3.7 to 4.3 in), the bill is around 1.8 cm (0.71 in), and the tarsus is 2.6 to 3.5 cm (1.0 to 1.4 in).[3]

The adult female is almost identical in outward appearance to the male, but the iridescence on her neck is less intense and more restricted to the rear and sides, whereas that on the breast is often very obscure.[3]

The white lower back of the pure rock dove is its best identification characteristic; the two black bars on its pale grey wings are also distinctive. The tail has a black band on the end, and the outer web of the tail feathers are margined with white. It is strong and quick on the wing, dashing out from sea caves, flying low over the water, its lighter grey rump showing well from above.[14]

Young birds show little lustre and are duller. Eye colour of the pigeon is generally orange, but a few pigeons may have white-grey eyes. The eyelids are orange and encapsulated in a grey-white eye ring. The feet are red to pink.[6]

When circling overhead, the white underwing of the bird becomes conspicuous. In its flight, behaviour, and voice, which is more of a dovecot coo than the phrase of the wood pigeon, it is a typical pigeon. Although it is a relatively strong flier, it also glides frequently, holding its wings in a very pronounced V shape as it does. [15] As prey birds, they must keep their vigilance, and when disturbed a pigeon within a flock will take off with a noisy clapping sound that cues for other pigeons to take to flight. The noise of the take-off increases the faster a pigeon beats its wings, thus advertising the magnitude of a perceived threat to its flockmates.[16]

Pigeons feed on the ground in flocks or individually. Pigeons are naturally granivorous, eating seeds that fit down their gullet. They may sometimes consume small invertebrates such as worms or insect larvae as a protein supplement. As they do not possess an enlarged cecum as in European wood pigeons, they cannot digest adult plant tissue; the various seeds they eat containing the appropriate nutrients they require.[17] [18] While most birds take small sips and tilt their heads backwards when drinking, pigeons are able to dip their bills into the water and drink continuously, without having to tilt their heads back. In cities they typically resort to scavenging human garbage, as unprocessed grain may be impossible to find. Pigeon groups typically consist of producers, which locate and obtain food, and scroungers, which feed on food obtained by the producers. Generally, groups of pigeons contain a greater proportion of scroungers than producers.[19]

Pigeons, especially homing or carrier breeds, are well known for their ability to find their way home from long distances. Despite these demonstrated abilities, wild rock doves are sedentary and rarely leave their local areas.[5]

A rock pigeon's lifespan ranges from 3–5 years in the wild to 15 years in captivity, though longer-lived specimens have been reported.[20] The main causes of mortality in the wild are predators and persecution by humans. The species was first introduced to North America in 1606 at Port Royal, Nova Scotia.[14]

Distribution and habitat

The rock dove has a restricted natural resident range in western and southern Europe, North Africa, and extending into South Asia. It is often found in pairs in the breeding season, but is usually gregarious.[3] The species (including ferals) has a large range, with an estimated global extent of occurrence of 10,000,000 km2 (3,900,000 sq mi). It has a large global population, including an estimated 17 to 28 million individuals in Europe.[1] Fossil evidence suggests the rock dove originated in southern Asia, and skeletal remains, unearthed in Israel, confirm its existence there for at least three-hundred thousand years.[4] However, this species has such a long history with humans that it is impossible to identify the species' original range exactly.[5]

Pigeons in the wild reside in rock formations, settling in crevices to nest. They nest communally, often forming large colonies of many hundreds of individuals.[21] Feral pigeons are usually unable to find these accommodations, so they must nest on building ledges, walls or statues. They may damage these structures via their feces; starving birds can only excrete urates, which over time corrodes masonry and metal. In contrast, a well-fed bird passes mostly solid feces, containing only small amounts of uric acid.

Reproduction

The rock dove breeds at any time of the year, but peak times are spring and summer. Nesting sites are along coastal cliff faces, as well as the artificial cliff faces created by apartment buildings with accessible ledges or roof spaces.[22]

The nest is a flimsy platform of straw and sticks, laid on a ledge, under cover, often on the window ledges of buildings.[5] Two white eggs are laid; incubation, shared by both parents, lasts 17 to 19 days.[6] The newly hatched squab (nestling) has pale yellow down and a flesh-coloured bill with a dark band. For the first few days, the baby squabs are tended and fed (through regurgitation) exclusively on "crop milk" (also called "pigeon milk" or "pigeon's milk"). The pigeon milk is produced in the crops of both parents in all species of pigeons and doves. The fledging period is about 30 days.[13]

Predators

With only their flying abilities protecting them from predation, rock pigeons are a favourite almost around the world for a wide range of raptors. In fact, with feral pigeons existing in almost every city in the world, they may form the majority of prey for several raptor species that live in urban areas. Peregrine falcons and Eurasian sparrowhawks are natural predators of pigeons that are quite adept at catching and feeding upon this species. Up to 80% of the diet of peregrine falcons in several cities that have breeding falcons is composed of feral pigeons.[23] Some common predators of feral pigeons in North America are opossums, raccoons, red-tailed hawks, great horned owls, eastern screech owls, and accipiters. The birds that prey on pigeons in North America can range in size from American kestrels to golden eagles[24] and can even include gulls, crows, and ravens. On the ground, the adults, their young, and their eggs are at risk from feral and domestic cats.[6] Doves and pigeons are considered to be game birds, as many species have been hunted and used for food in many of the countries in which they are native.[25]

The body feathers have dense, fluffy bases and are loosely attached to the skin, hence they drop out easily. When a predator catches it, large numbers of feathers come out in the attacker's mouth, and the pigeon may use this temporary distraction to make an escape.[26] It also tends to drop the tail feathers when preyed upon or under traumatic conditions, probably as a distraction mechanism.[27]

Preening

Pigeons primarily use powder down feathers for preening, which gives a soft and silky feel to their plumage. They have no preen gland or at times have very rudimentary preen glands, so oil is not used for preening. Rather, powder down feathers are spread across the body. These have a tendency to disintegrate, and the powder, akin to talcum powder, helps maintain the plumage.[26] Some varieties of domestic pigeons have modified feathers called "fat quills". These feathers contain yellow, oil-like fat that derives from the same cells as powder down. This is used while preening and helps reduce bacterial degradation of feathers by feather bacilli.[28]

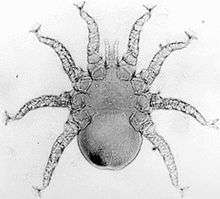

Parasites

| Tinaminyssus melloi, a nasal mite. | Pigeon louse fly (Pseudolynchia canariensis), a blood-sucking ectoparasite. |

Pigeons may harbour a diverse parasite fauna.[29] They often host the intestinal helminths Capillaria columbae and Ascaridia columbae. Their ectoparasites include the ischnoceran lice Columbicola columbae, Campanulotes bidentatus compar, the amblyceran lice Bonomiella columbae, Hohorstiella lata, Colpocephalum turbinatum, the mites Tinaminyssus melloi, Dermanyssus gallinae, Dermoglyphus columbae, Falculifer rostratus, and Diplaegidia columbae. The hippoboscid fly Pseudolynchia canariensis is a typical blood-sucking ectoparasite of pigeons, found only in tropical and subtropical regions.

Human health

Contact with pigeon droppings poses a minor risk of contracting histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and psittacosis,[30] and long-term exposure to both droppings and feathers can induce an allergy known as bird fancier's lung. Pigeons are not a major concern in the spread of West Nile virus; though they can contract it, they do not appear to be able to transmit it.[31] Pigeons are, however, at potential risk for carrying and spreading avian influenza. One study has shown that adult pigeons are not clinically susceptible to the most dangerous strain of avian influenza, H5N1, and that they did not transmit the virus to chickens.[32] Other studies have presented evidence of clinical signs and neurological lesions resulting from infection, but found that the pigeons did not transmit the disease to chickens reared in direct contact with them.[33][34] Pigeons were found to be "resistant or minimally susceptible" to other strains of avian influenza, such as the H7N7.[35]

Domestication

Rock doves have been domesticated for several thousand years, giving rise to the domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica).[6] Numerous breeds of fancy pigeons of all sizes, colours, and types have been bred.[36] Domesticated pigeons are used as homing pigeons as well as food and pets. They were in the past also used as carrier pigeons, and so-called war pigeons have played significant roles during wartime, including delivering urgent medicines, with many pigeons having received bravery awards and medals for their services in saving hundreds of human lives, including, notably, the British pigeon Cher Ami, which received the Croix de Guerre for actions during World War I, and the Irish Paddy and the American G.I. Joe, which both received the Dickin Medal, amongst 32 pigeons to receive this award, for their actions during World War II, more than any other species of animal [6]

Feral pigeon

Many domestic birds have got lost, escaped or been released over the years, and have given rise to feral pigeons. These show a variety of plumages, although many have the blue-barred pattern as does the pure rock dove. Feral pigeons are found in cities and towns all over the world.[37] The scarcity of the pure wild species is partly due to interbreeding with feral birds.[15]

Stages of lifecycle

Columba livia - MHNT

Columba livia - MHNT Egg, measured in centimetres

Egg, measured in centimetres Nest with two eggs

Nest with two eggs Nestlings, one day

Nestlings, one day Nestling, five days

Nestling, five days Nestlings, about 10 days

Nestlings, about 10 days Young bird, 22 days

Young bird, 22 days Feral pigeons in courtship

Feral pigeons in courtship Rock dove 18 days old in its nest and one egg

Rock dove 18 days old in its nest and one egg

Osmoregulation

Challenges

C. livia pigeons drink directly by water source or indirectly from the food they ingest. They drink water through a process called double-suction mechanism.[38] The daily diet of the pigeon places many physiological challenges that it must overcome through osmoregulation. Protein intake, for example, causes an excess of toxins of amine groups when it is broken down for energy.[38] To regulate this excess and secrete these unwanted toxins, C. livia must remove the amine groups as uric acid. Nitrogen excretion through uric acid can be considered an advantage because it does not require a lot of water, but producing it takes more energy because of its complex molecular composition.[38]

Pigeons adjust their drinking rates and food intake in parallel, and when adequate water is unavailable for excretion, food intake is limited to maintain water balance. As this species inhabits arid environments, research attributes this to their strong flying capabilities to reach the available water sources, not because of exceptional potential for water conservation. C. livia kidneys, like mammalian kidneys, are capable of producing urine hyperosmotic to the plasma using the processes of filtration, reabsorption, and secretion.[39] The medullary cones function as countercurrent units that achieve the production of hyperosmotic urine. Hyperosmotic urine can be understood in light of the law of diffusion and osmolarity.[40]

Organ of osmoregulation

Unlike a number of other bird species which have the salt gland as the primary osmoregulatory organ, C. livia does not use its salt gland.[41] It uses the function of the kidneys to maintain homeostatic balance of ions such as sodium and potassium while preserving water quantity in the body.[42] Filtration of the blood, reabsorption of ions and water, and secretion of uric acid are all components of the kidney's process.

Special adaptations

Eggshell gas exchange and water loss

Gas exchange across eggshells results in water loss from the egg. However, the egg must retain enough water to hydrate the embryo. As a result, changing temperatures and humidity can affect the eggshell's architecture.[43]:2 Behavioral adaptations in Columba livia and other birds, such as the incubation of their eggs, can help with the effects of these changing environments.[43]:2 It was found that eggshell architecture undergoes selection decoupled from behavioural effects, and that humidity may be a driving selective pressure. Low humidity requires enough water to keep the embryo from desiccation, and high humidity needs enough water loss to facilitate the initiation of pulmonary respiration.[43]:3 The water loss from the eggshell is directly linked to the growth rate of the species. The ability of the embryo to tolerate extreme water loss is due to the parental behaviour in species colonising in different environments. Studies show that wild habitats of C. livia and other birds have a higher rate tolerance of various humidity levels, but C. livia prefers areas where the humidity closely matches its native breeding conditions.[43]:9 The pore areas of the shells allow water to diffuse in and out of the shell, preventing the possible harming of the embryo due to the high rates of water retention. If an eggshell is thinner, it can cause a decrease in pore length, and an increase in conductance and pore area. A thinner eggshell can also cause a decrease in mechanical restriction of the embryo.[43]:9

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Columba livia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T22690066A86070297. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22690066A86070297.en.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Columba livia". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Gibbs, David; Eustace Barnes; John Cox (2010-06-30). Pigeons and Doves: A Guide to the Pigeons and Doves of the World. United Kingdom: Pica Press. ISBN 978-1-873403-60-0.

- Blechman, Andrew (2007). Pigeons-The fascinating saga of the world's most revered and reviled bird. St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-3641-9.

- "Rock Pigeon". All About Birds. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- Levi, Wendell (1977). The Pigeon. Sumter, S.C.: Levi Publishing Co, Inc. ISBN 0-85390-013-2.

- "Rock Pigeon Life History, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- In J.F. Gmelin's edition of Linné's Systema Naturae appeared in Leipzig, 1788-93.

- James A. Jobling. Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Bloomsbury Publishing p. 114 ISBN 1408125013

- Liddell, Henry George & Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- "English Names Version 2". IOC World Bird List. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Jahan, Shah. "Feral Pigeon". The Birds I Saw. Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- White, Helen. "Rock Pigeons". www.diamonddove.info. Helen White. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- Wright, Mike. "Wildlife Profiles: Pigeon". Arkansas Urban Wildlife. Archived from the original on 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- Davis, J.Michael (1975). "Socially induced flight reactions in pigeons". Animal Behaviour. 23: 597–601. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(75)90136-0.

- https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/rock-pigeon

- https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/wilson/v107n01/p0093-p0121.pdf

- Dugatkin, Lee Alan (2014). Principles of Animal Behavior (3 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton Company. pp. 373–376. ISBN 9780393920451.

- "Columba livia (domest.)". BBC Science & Nature. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/rock-pigeon

- "Columba livia". Australian Museum Online. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- White, Clayton M.; Nancy J. Clum; Tom J. Cade & W. Grainger Hunt. "Peregrine Falcon". Birds of North America Online. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- Roof, Jennifer (2001). "Columba livia common pigeon". Animal Diversity Web University of Michigan. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Butler, Krissy Anne. "Keeping & Breeding Doves & Pigeons". Game Bird Gazette Magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- "Columbiformes (Pigeons, Doves, and Dodos)". Encyclopedia.com. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia COPYRIGHT 2004 The Gale Group Inc. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Naish, Darren. "The detachable tails of pigeons". Scienceblogs.com. 2006-2017 ScienceBlogs LLC. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- Peters, Anne; Klonczinski, Eva; Delhey, Kaspar (March 2010). "Fat quill secretion in pigeons: Could it function as a cosmetic?". Animal Biology. 60: 69–78. doi:10.1163/157075610X12610595764219.

- Rózsa L (1990). "The ectoparasite fauna of feral pigeon populations in Hungary" (PDF). Parasitologia Hungarica. 23: 115–119.

- "Facts about pigeon-related diseases". The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- Chalmers, Dr Gordon A. "West Nile Virus and Pigeons". Panorama lofts. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved 2008-02-18.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Liu Y, Zhou J, Yang H, et al. (2007). "Susceptibility and transmissibility of pigeons to Asian lineage highly pathogenic avian influenza virus subtype H5N1". Avian Pathol. 36 (6): 461–5. doi:10.1080/03079450701639335. PMID 17994324.

- Klopfleisch R, Werner O, Mundt E, Harder T, Teifke JP (2006). "Neurotropism of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/chicken/Indonesia/2003 (H5N1) in experimentally infected pigeons (Columbia livia f. domestica)". Vet. Pathol. 43 (4): 463–70. doi:10.1354/vp.43-4-463. PMID 16846988.

- Werner O, Starick E, Teifke J, et al. (2007). "Minute excretion of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/chicken/Indonesia/2003 (H5N1) from experimentally infected domestic pigeons (Columbia livia) and lack of transmission to sentinel chickens". J. Gen. Virol. 88 (Pt 11): 3089–93. doi:10.1099/vir.0.83105-0. PMID 17947534.

- Panigrahy B, Senne DA, Pedersen JC, Shafer AL, Pearson JE (1996). "Susceptibility of pigeons to avian influenza". Avian Dis. 40 (3): 600–4. doi:10.2307/1592270. JSTOR 1592270. PMID 8883790.

- McClary, Douglas (1999). Pigeons for Everyone. Great Britain: Winckley Press. ISBN 0-907769-28-4.

- "Why study pigeons? To understand why there are so many colors of feral pigeons". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Ritchison, Gary. "Ornithology (Bio 554/754):Urinary System, Salt Glands, and Osmoregulation". Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- Abs, Michael (1983). Physiology and behavior of Pigeon. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-042950-0.

- Dorit, Walker; Barnes; Robert, Warren & Robert (1991). Zoology. Orlando, Florida: Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 0-03-030504-7.

- SCHMIDT-NIELSEN, KNUT. "The Salt-Secreting Gland of Marine Birds" (PDF). American Heart Association. Retrieved Nov 8, 2013.

- Abs, Michael (1983). Physiology and Behaviour of the Pigeon. London: Academic Press Inc. pp. 41–51. ISBN 0-12-042950-0.

- Stein, Laura (May 2009). "Evolution of Eggshell Architecture Accompanying Rapid Range Expansion in a Passerine Bird".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Columba livia. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Columba livia |

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 3.4 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- "Rock Dove media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Rock Pigeon photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Rock dove - Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds.