Sulfur hexafluoride

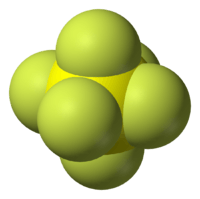

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) is an inorganic, colorless, odorless, non-flammable, non-toxic but extremely potent greenhouse gas, and an excellent electrical insulator.[7] SF

6 has an octahedral geometry, consisting of six fluorine atoms attached to a central sulfur atom. It is a hypervalent molecule. Typical for a nonpolar gas, it is poorly soluble in water but quite soluble in nonpolar organic solvents. It is generally transported as a liquefied compressed gas. It has a density of 6.12 g/L at sea level conditions, considerably higher than the density of air (1.225 g/L).

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sulfur hexafluoride | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Hexafluoro-λ6-sulfane[1] | |||

| Other names

Elagas Esaflon | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.018.050 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 2752 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Sulfur+hexafluoride | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1080 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| SF6 | |||

| Molar mass | 146.06 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | odorless[2] | ||

| Density | 6.17 g/L | ||

| Melting point | −64 °C; −83 °F; 209 K | ||

| Boiling point | −50.8 °C (−59.4 °F; 222.3 K) | ||

| Critical point (T, P) | 45.51±0.1 °C, 3.749±0.01 MPa[3] | ||

| 0.003% (25 °C)[2] | |||

| Solubility | slightly soluble in water, very soluble in ethanol, hexane, benzene | ||

| Vapor pressure | 2.9 MPa (at 21.1 °C) | ||

| −44.0×10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Thermal conductivity |

| ||

| Viscosity | 15.23 μPa·s[5] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Orthorhombic, oP28 | |||

| Oh | |||

| Orthogonal hexagonal | |||

| Octahedral | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) |

0.097 kJ/(mol·K) (constant pressure) | ||

Std molar entropy (S |

292 J·mol−1·K−1[6] | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1209 kJ·mol−1[6] | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| V08DA05 (WHO) | |||

| License data | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS | ||

| S-phrases (outdated) | S38 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 1000 ppm (6000 mg/m3)[2] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1000 ppm (6000 mg/m3)[2] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[2] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related sulfur fluorides |

Disulfur decafluoride | ||

Related compounds |

Selenium hexafluoride Sulfuryl fluoride | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Synthesis and reactions

SF

6 can be prepared from the elements through exposure of S

8 to F

2. This was also the method used by the discoverers Henri Moissan and Paul Lebeau in 1901. Some other sulfur fluorides are cogenerated, but these are removed by heating the mixture to disproportionate any S

2F

10 (which is highly toxic) and then scrubbing the product with NaOH to destroy remaining SF

4.

Alternatively, utilizing bromine, sulfur hexafluoride can be synthesized from SF4 and CoF3 at lower temperatures (e.g. 100 °C), as follows:[8]

- 2 CoF3 + SF4 + [Br2] → SF6 + 2 CoF2 + [Br2]

There is virtually no reaction chemistry for SF

6. A main contribution to the inertness of SF6 is the steric hindrance of the sulfur atom, whereas its heavier group 16 counterparts, such as SeF6 are more reactive than SF6 as a result of less steric hindrance (See hydrolysis example).[9] It does not react with molten sodium below its boiling point,[10] but reacts exothermically with lithium.

Applications

More than 10,000 tons of SF

6 are produced per year, most of which (over 8,000 tons) is used as a gaseous dielectric medium in the electrical industry.[11] Other main uses include an inert gas for the casting of magnesium, and as an inert filling for insulated glazing windows.

Dielectric medium

SF

6 is used in the electrical industry as a gaseous dielectric medium for high-voltage circuit breakers, switchgear, and other electrical equipment, often replacing oil-filled circuit breakers (OCBs) that can contain harmful PCBs. SF

6 gas under pressure is used as an insulator in gas insulated switchgear (GIS) because it has a much higher dielectric strength than air or dry nitrogen. The high dielectric strength is a result of the gas's high electronegativity and density. This property makes it possible to significantly reduce the size of electrical gear. This makes GIS more suitable for certain purposes such as indoor placement, as opposed to air-insulated electrical gear, which takes up considerably more room. Gas-insulated electrical gear is also more resistant to the effects of pollution and climate, as well as being more reliable in long-term operation because of its controlled operating environment. Exposure to an arc chemically breaks down SF

6 though most of the decomposition products tend to quickly re-form SF

6, a process termed "self-healing".[12] Arcing or corona can produce disulfur decafluoride (S

2F

10), a highly toxic gas, with toxicity similar to phosgene. S

2F

10 was considered a potential chemical warfare agent in World War II because it does not produce lacrimation or skin irritation, thus providing little warning of exposure.

SF

6 is also commonly encountered as a high voltage dielectric in the high voltage supplies of particle accelerators, such as Van de Graaff generators and Pelletrons and high voltage transmission electron microscopes.

| Look up fluoroketone in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Alternatives to SF

6 as a dielectric gas include several fluoroketones.[13][14]

Medical use

SF

6 is used to provide a tamponade or plug of a retinal hole in retinal detachment repair operations[15] in the form of a gas bubble. It is inert in the vitreous chamber[16] and initially doubles its volume in 36 hours before being absorbed in the blood in 10–14 days.[17]

SF

6 is used as a contrast agent for ultrasound imaging. Sulfur hexafluoride microbubbles are administered in solution through injection into a peripheral vein. These microbubbles enhance the visibility of blood vessels to ultrasound. This application has been used to examine the vascularity of tumours.[18] It remains visible in the blood for 3 to 8 minutes, and is exhaled by the lungs.[19]

Tracer compound

Sulfur hexafluoride was the tracer gas used in the first roadway air dispersion model calibration; this research program was sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and conducted in Sunnyvale, California on U.S. Highway 101.[20] Gaseous SF

6 is used as a tracer gas in short-term experiments of ventilation efficiency in buildings and indoor enclosures, and for determining infiltration rates. Two major factors recommend its use: its concentration can be measured with satisfactory accuracy at very low concentrations, and the Earth's atmosphere has a negligible concentration of SF

6.

Sulfur hexafluoride was used as a non-toxic test gas in an experiment at St. John's Wood tube station in London, United Kingdom on 25 March 2007.[21] The gas was released throughout the station, and monitored as it drifted around. The purpose of the experiment, which had been announced earlier in March by the Secretary of State for Transport Douglas Alexander, was to investigate how toxic gas might spread throughout London Underground stations and buildings during a terrorist attack.

Sulfur hexafluoride is also routinely used as a tracer gas in laboratory fume hood containment testing. The gas is used in the final stage of ASHRAE 110 fume hood qualification. A plume of gas is generated inside of the fume hood and a battery of tests are performed while a gas analyzer arranged outside of the hood samples for SF6 to verify the containment properties of the fume hood.

It has been used successfully as a tracer in oceanography to study diapycnal mixing and air-sea gas exchange.

Other uses

- The United States Navy's Mark 50 torpedo closed Rankine-cycle propulsion system is powered by sulfur hexafluoride in an exothermic reaction with solid lithium.[22]

- SF

6 plasma is also used in the semiconductor industry as an etchant. SF

6 breaks down in the plasma into sulfur and fluorine, the fluorine plasma performing the etching.[23] - The magnesium industry uses large amounts of SF

6 as inert gas to fill casting forms.[24] - Pressurizes waveguides in high-power microwave systems. The gas insulates the waveguide, preventing internal arcing.

- Has been used in electrostatic loudspeakers because of its high dielectric strength and high molecular weight.[25]

- Was used to fill Nike Air bags in all of their shoes from 1992-2006.[26]

- Feedstock for production of the chemical weapon disulfur decafluoride.

- For entertainment purposes, when breathed, SF

6 causes the voice to become significantly deeper, due to its density being so much higher than air, as seen in this video, here. This is related to the more well-known effect of breathing low-density helium, which causes someone's voice to become much higher. Both of these effects should only be attempted with caution as these gases displace oxygen that the lungs are attempting to extract from the air. Sulfur hexafluoride is also mildly anesthetic.[27] - For science demonstrations / magic as "invisible water" since a light foil boat can be floated in a tank, as will an air filled balloon

Greenhouse gas

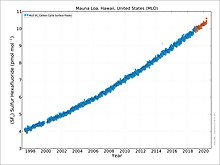

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, SF

6 is the most potent greenhouse gas that it has evaluated, with a global warming potential of 23,900[28] times that of CO

2 when compared over a 100-year period. Sulfur hexafluoride is inert in the troposphere and stratosphere and is extremely long-lived, with an estimated atmospheric lifetime of 800–3,200 years.[29]

Measurements of SF6 show that its global average mixing ratio has increased by about 0.2 parts per trillion per year to over 9 ppt as of February 2018.[30][31] Average global SF6 concentrations increased by about seven percent per year during the 1980s and 1990s, mostly as the result of its use in the magnesium production industry, and by electrical utilities and electronics manufacturers. Given the small amounts of SF6 released compared to carbon dioxide, its overall contribution to global warming is estimated to be less than 0.2 percent.[32] Alternatives are being tested.[33]

In Europe, SF

6 falls under the F-Gas directive which ban or control its use for several applications. Since 1 January 2006, SF

6 is banned as a tracer gas and in all applications except high-voltage switchgear.[34] It was reported in 2013 that a three-year effort by the United States Department of Energy to identify and fix leaks at its laboratories in the United States such as the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, where the gas is used as a high voltage insulator, had been productive, cutting annual leaks by 16,000 kilograms (35,000 pounds). This was done by comparing purchases with inventory, assuming the difference was leaked, then locating and fixing the leaks.[7]

Physiological effects and precautions

Like xenon, sulfur hexafluoride is a nontoxic gas, but by displacing oxygen in the lungs, it also carries the risk of asphyxia if too much is inhaled.[35] Since it is more dense than air, a substantial quantity of gas, when released, will settle in low-lying areas and present a significant risk of asphyxiation if the area is entered. That is particularly relevant to its use as an insulator in electrical equipment since workers may be in trenches or pits below equipment containing SF

6.[36]

As with all gases, the density of SF

6 affects the resonance frequencies of the vocal tract, thus changing drastically the vocal sound qualities, or timbre, of those who inhale it. It does not affect the vibrations of the vocal folds. The density of sulfur hexafluoride is relatively high at room temperature and pressure due to the gas's large molar mass. Unlike helium, which has a molar mass of about 4 g/mol and pitches the voice up, SF

6 has a molar mass of about 146 g/mol, and the speed of sound through the gas is about 134 m/s at room temperature, pitching the voice down. For comparison, the molar mass of air, which is about 80% nitrogen and 20% oxygen, is approximately 30 g/mol which leads to a speed of sound of 343 m/s.[37]

Sulfur hexafluoride has an anesthetic potency slightly lower than nitrous oxide;[38] Sulfur hexafluoride is classified as a mild anesthetic.[39]

See also

- Selenium hexafluoride

- Tellurium hexafluoride

- Uranium hexafluoride

- Hypervalent molecule

- Halocarbon—another group of major greenhouse gases

References

- "Sulfur Hexafluoride - PubChem Public Chemical Database". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0576". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Horstmann, Sven; Fischer, Kai; Gmehling, Jürgen (2002). "Measurement and calculation of critical points for binary and ternary mixtures". AIChE Journal. 48 (10): 2350–2356. doi:10.1002/aic.690481024. ISSN 0001-1541.

- Assael, M. J.; Koini, I. A.; Antoniadis, K. D.; Huber, M. L.; Abdulagatov, I. M.; Perkins, R. A. (2012). "Reference Correlation of the Thermal Conductivity of Sulfur Hexafluoride from the Triple Point to 1000 K and up to 150 MPa". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 41 (2): 023104–023104–9. doi:10.1063/1.4708620. ISSN 0047-2689.

- Assael, M. J.; Kalyva, A. E.; Monogenidou, S. A.; Huber, M. L.; Perkins, R. A.; Friend, D. G.; May, E. F. (2018). "Reference Values and Reference Correlations for the Thermal Conductivity and Viscosity of Fluids". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 47 (2): 021501. doi:10.1063/1.5036625. ISSN 0047-2689. PMC 6463310. PMID 30996494.

- Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- Michael Wines (June 13, 2013). "Department of Energy's Crusade Against Leaks of a Potent Greenhouse Gas Yields Results". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Winter, R. W.; Pugh, J. R.; Cook, P. W. (January 9–14, 2011). SF5Cl, SF4 and SF6: Their Bromine−facilitated Production & a New Preparation Method for SF5Br. 20th Winter Fluorine Conference.

- Duward Shriver; Peter Atkins (2010). Inorganic Chemistry. W. H. Freeman. p. 409. ISBN 978-1429252553.

- Raj, Gurdeep (2010). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry: Volume II (12th ed.). GOEL Publishing House. p. 160. Extract of page 160

- Constantine T. Dervos; Panayota Vassilou (2012). Sulfur Hexafluoride: Global Environmental Effects and Toxic Byproduct Formation. Taylor and Francis.

- Jakob, Fredi; Perjanik, Nicholas. "Sulfur Hexafluoride, A Unique Dielectric" (PDF). Analytical ChemTech International, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2017-10-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kieffel, Yannick; Biquez, Francois (1 June 2015). "SF<inf>6</inf> alternative development for high voltage switchgears". SF6 alternative development for high voltage switchgears. pp. 379–383. doi:10.1109/ICACACT.2014.7223577. ISBN 978-1-4799-7352-1 – via IEEE Xplore.

- Daniel A. Brinton; C. P. Wilkinson (2009). Retinal detachment: principles and practice. Oxford University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0199716210.

- Gholam A. Peyman, M.D., Stephen A. Meffert, M.D., Mandi D. Conway (2007). Vitreoretinal Surgical Techniques. Informa Healthcare. p. 157. ISBN 978-1841846262.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hilton, G. F.; Das, T.; Majji, A. B.; Jalali, S. (1996). "Pneumatic retinopexy: Principles and practice". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 44 (3): 131–143. PMID 9018990.

- Lassau N, Chami L, Benatsou B, Peronneau P, Roche A (December 2007). "Dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (DCE-US) with quantification of tumor perfusion: a new diagnostic tool to evaluate the early effects of antiangiogenic treatment". Eur Radiol. 17 (Suppl. 6): F89–F98. doi:10.1007/s10406-007-0233-6. PMID 18376462.

- "SonoVue, INN-sulphur hexafluoride - Annex I - Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- C Michael Hogan (September 10, 2011). "Air pollution line source". Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "'Poison gas' test on Underground". BBC News. 25 March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Hughes, T.G.; Smith, R.B. & Kiely, D.H. (1983). "Stored Chemical Energy Propulsion System for Underwater Applications". Journal of Energy. 7 (2): 128–133. doi:10.2514/3.62644.

- Y. Tzeng & T.H. Lin (September 1987). "Dry Etching of Silicon Materials in SF

6 Based Plasmas" (PDF). Journal of the Electrochemical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013. - Scott C. Bartos (February 2002). "Update on EPA's manesium industry partnership for climate protection" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Dick Olsher (October 26, 2009). "Advances in loudspeaker technology - A 50 year prospective". The Absolute Sound. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Stanley Holmes (September 24, 2006). "Nike Goes For The Green". Bloomberg Business Week Magazine. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Edmond I Eger MD; et al. (September 10, 1968). "Anesthetic Potencies of Sulfur Hexafluoride, Carbon Tetrafluoride, Chloroform and Ethrane in Dogs: Correlation with the Hydrate and Lipid Theories of Anesthetic Action". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology - The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. 30 (2): 127–134.

- "2.10.2 Direct Global Warming Potentials". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- A. R. Ravishankara, S. Solomon, A. A. Turnipseed, R. F. Warren; Solomon; Turnipseed; Warren (8 January 1993). "Atmospheric Lifetimes of Long-Lived Halogenated Species". Science. 259 (5092): 194–199. Bibcode:1993Sci...259..194R. doi:10.1126/science.259.5092.194. PMID 17790983. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2013.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Chromatograph for Atmospheric Trace Species SF6 Mixing Ratio". US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) data from hourly in situ samples analyzed on a gas chromatograph located at Cape Matatulu (SMO)". August 27, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "SF6 Sulfur Hexafluoride". PowerPlantCCS Blog. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "g3, the SF6-free solution in practice | Think Grid". think-grid.org. 18 February 2019.

- "Climate: MEPs give F-gas bill a 'green boost'". EurActiv.com. 13 October 2005. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Sulfur Hexafluoride". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Guide to the safe use of SF6 in gas". UNIPEDE/EURELECTRIC. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- "Physics in Speech". University of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Adriani, John (1962). The Chemistry and Physics of Anesthesia (2nd ed.). Illinois: Thomas Books. p. 319. ISBN 9780398000110.

- Weaver, Raymond H.; Virtue, Robert W. (1 November 1952). "THE MILD ANESTHETIC PROPERTIES OF SULFUR HEXAFLUORIDE". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. pp. 605–607.

Further reading

- "Sulfur hexafluoride". Air Liquide Gas Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Christophorou, Loucas G.; Isidor Sauers, eds. (1991). Gaseous Dielectrics VI. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-43894-3.

- Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Khalifa, Mohammad (1990). High-Voltage Engineering: Theory and Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-8128-6. OCLC 20595838.

- Maller, V. N.; Naidu, M. S. (1981). Advantages in High Voltage Insulation and Arc Interruption in SF6 and Vacuum. Oxford; New York: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-024726-7. OCLC 7866855.

- SF6 Reduction Partnership for Electric Power Systems

- Matt McGrath (September 13, 2019). "Climate change: Electrical industry's 'dirty secret' boosts warming". BBC News. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

External links

- Fluoride and compounds fact sheet— National Pollutant Inventory

- High GWP Gases and Climate Change from the U.S. EPA website

- International Conference on SF6 and the Environment (related archive)

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards