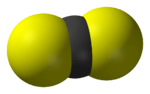

Carbon disulfide

Carbon disulfide is a colorless volatile liquid with the formula CS2. The compound is used frequently as a building block in organic chemistry as well as an industrial and chemical non-polar solvent. It has an "ether-like" odor, but commercial samples are typically contaminated with foul-smelling impurities.[7]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Methanedithione | |

| Other names

Carbon bisulfide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.767 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1131 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CS2 | |

| Molar mass | 76.13 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid Impure: light-yellow |

| Odor | Chloroform (pure) Foul (commercial) |

| Density | 1.539 g/cm3 (−186°C) 1.2927 g/cm3 (0 °C) 1.266 g/cm3 (25 °C)[1] |

| Melting point | −111.61 °C (−168.90 °F; 161.54 K) |

| Boiling point | 46.24 °C (115.23 °F; 319.39 K) |

| 2.58 g/L (0 °C) 2.39 g/L (10 °C) 2.17 g/L (20 °C)[2] 0.14 g/L (50 °C)[1] | |

| Solubility | Soluble in alcohol, ether, benzene, oil, CHCl3, CCl4 |

| Solubility in formic acid | 4.66 g/100 g[1] |

| Solubility in dimethyl sulfoxide | 45 g/100 g (20.3 °C)[1] |

| Vapor pressure | 48.1 kPa (25 °C) 82.4 kPa (40 °C)[3] |

| −42.2·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.627[4] |

| Viscosity | 0.436 cP (0 °C) 0.363 cP (20 °C) |

| Structure | |

| Linear | |

| 0 D (20 °C)[1] | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) |

75.73 J/(mol·K)[1] |

Std molar entropy (S |

151 J/(mol·K)[1] |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

88.7 kJ/mol[1] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) |

64.4 kJ/mol[1] |

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

1687.2 kJ/mol[3] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page |

| GHS pictograms |    |

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements |

H225, H315, H319, H361, H372[4] |

| P210, P281, P305+351+338, P314[4] ICSC 0022 | |

| Inhalation hazard | Irritant; toxic |

| Eye hazard | Irritant |

| Skin hazard | Irritant |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | −43 °C (−45 °F; 230 K)[1] |

| 102 °C (216 °F; 375 K)[1] | |

| Explosive limits | 1.3–50%[5] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

3188 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

LC50 (median concentration) |

>1670 ppm (rat, 1 h) 15500 ppm (rat, 1 h) 3000 ppm (rat, 4 h) 3500 ppm (rat, 4 h) 7911 ppm (rat, 2 h) 3165 ppm (mouse, 2 h)[6] |

LCLo (lowest published) |

4000 ppm (human, 30 min)[6] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 20 ppm C 30 ppm 100 ppm (30-minute maximum peak)[5] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1 ppm (3 mg/m3) ST 10 ppm (30 mg/m3) [skin][5] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

500 ppm[5] |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

Carbon dioxide Carbonyl sulfide Carbon diselenide |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Occurrence, manufacture, properties

Small amounts of carbon disulfide are released by volcanic eruptions and marshes. CS2 once was manufactured by combining carbon (or coke) and sulfur at high temperatures.

- C + 2S → CS2

A lower-temperature reaction, requiring only 600 °C, utilizes natural gas as the carbon source in the presence of silica gel or alumina catalysts:[7]

- 2 CH4 + S8 → 2 CS2 + 4 H2S

The reaction is analogous to the combustion of methane.

Global production/consumption of carbon disulfide is approximately one million tonnes, with China consuming 49%, followed by India at 13%, mostly for the production of rayon fiber.[8] United States production in 2007 was 56,000 tonnes.[9]

Reactions

CS2 is highly flammable. Its combustion affords sulfur dioxide according to this ideal stoichiometry:

- CS2 + 3 O2 → CO2 + 2 SO2

With nucleophiles

Compared to the isoelectronic carbon dioxide, CS2 is a weaker electrophile. While, however, reactions of nucleophiles with CO2 are highly reversible and products are only isolated with very strong nucleophiles, the reactions with CS2 are thermodynamically more favored allowing the formation of products with less reactive nucleophiles.[12] For example, amines afford dithiocarbamates:

- 2 R2NH + CS2 → [R2NH2+][R2NCS2−]

Xanthates form similarly from alkoxides:

- RONa + CS2 → [Na+][ROCS2−]

This reaction is the basis of the manufacture of regenerated cellulose, the main ingredient of viscose, rayon and cellophane. Both xanthates and the related thioxanthates (derived from treatment of CS2 with sodium thiolates) are used as flotation agents in mineral processing.

Sodium sulfide affords trithiocarbonate:

- Na2S + CS2 → [Na+]2[CS32−]

Carbon disulfide does not hydrolyze readily, although the process is catalyzed by an enzyme carbon disulfide hydrolase.

Reduction

Reduction of carbon disulfide with sodium affords sodium 1,3-dithiole-2-thione-4,5-dithiolate together with sodium trithiocarbonate:[13]

- 4 Na + 4 CS2 → Na2C3S5 + Na2CS3

Chlorination

Chlorination of CS2 provides a route to carbon tetrachloride:[7]

This conversion proceeds via the intermediacy of thiophosgene, CSCl2.

Polymerization

CS2 polymerizes upon photolysis or under high pressure to give an insoluble material called car-sul or "Bridgman's black", named after the discoverer of the polymer, Percy Williams Bridgman.[15] Trithiocarbonate (-S-C(S)-S-) linkages comprise, in part, the backbone of the polymer, which is a semiconductor.[16]

Uses

The principal industrial uses of carbon disulfide, consuming 75% of the annual production, are the manufacture of viscose rayon and cellophane film.[17]

It is also a valued intermediate in chemical synthesis of carbon tetrachloride. It is widely used in the synthesis of organosulfur compounds such as metam sodium, xanthates, dithiocarbamates, which are used in extractive metallurgy and rubber chemistry.

Niche uses

It can be used in fumigation of airtight storage warehouses, airtight flat storages, bins, grain elevators, railroad box cars, shipholds, barges and cereal mills.[18] Carbon disulfide is also used as an insecticide for the fumigation of grains, nursery stock, in fresh fruit conservation and as a soil disinfectant against insects and nematodes.[19]

Health effects

Carbon disulfide has been linked to both acute and chronic forms of poisoning, with a diverse range of symptoms.[20] Typical recommended TLV is 30 mg/m3, 10 ppm. Possible symptoms include, but are not limited to, tingling or numbness, loss of appetite, blurred vision, cramps, muscle weakness, pain, neurophysiological impairment, priapism, erectile dysfunction, psychosis, keratitis, and death by respiratory failure.[17][21]

Occupational exposure to carbon disulfide is associated with cardiovascular disease, particularly stroke.[22]

History

In 1796, the German chemist Wilhelm August Lampadius (1772–1842) first prepared carbon disulfide by heating pyrite with moist charcoal. He called it "liquid sulfur" (flüssig Schwefel).[23] The composition of carbon disulfide was finally determined in 1813 by the team of the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848) and the Swiss-British chemist Alexander Marcet (1770–1822).[24] Their analysis was consistent with an empirical formula of CS2.[25]

References

- "Properties of substance: carbon disulfide". chemister.ru.

- Seidell, Atherton; Linke, William F. (1952). Solubilities of Inorganic and Organic Compounds. Van Nostrand.

- Carbon disulfide in Linstrom, Peter J.; Mallard, William G. (eds.); NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg (MD), http://webbook.nist.gov (retrieved 2014-05-27).

- Sigma-Aldrich Co., Carbon disulfide. Retrieved on 2014-05-27.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0104". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Carbon disulfide". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Holleman, Arnold Frederik; Wiberg, Egon (2001), Wiberg, Nils (ed.), Inorganic Chemistry, translated by Eagleson, Mary; Brewer, William, San Diego/Berlin: Academic Press/De Gruyter, ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- "Carbon Disulfide report from IHS Chemical". Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- "Chemical profile: carbon disulfide from ICIS.com". Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- "Carbon Disulfide". Akzo Nobel.

- Park, Tae-Jin; Banerjee, Sarbajit; Hemraj-Benny, Tirandai; Wong, Stanislaus S. (2006). "Purification strategies and purity visualization techniques for single-walled carbon nanotubes". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 16 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1039/b510858f. S2CID 581451.

- Li, Zhen; Mayer, Robert J.; Ofial, Armin R.; Mayr, Herbert (2020-04-27). "From Carbodiimides to Carbon Dioxide: Quantification of the Electrophilic Reactivities of Heteroallenes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 142 (18): 8383–8402. doi:10.1021/jacs.0c01960. PMID 32338511.

- "4,5-Dibenzoyl-1,3-dithiole-1-thione". Org. Synth. 73: 270. 1996. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.073.0270.

- Werner, Helmut (1982). "Novel Coordination Compounds formed from CS2 and Heteroallenes". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 43: 165–185. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(00)82095-0.

- Bridgman, P.W. (1941). "Explorations toward the limit of utilizable pressures". Journal of Applied Physics. 12: 461–469.

- Ochiai, Bungo; Endo, Takeshi (2005). "Carbon dioxide and carbon disulfide as resources for functional polymers". Progress in Polymer Science. 30 (2): 183–215. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2005.01.005.

- Lay, Manchiu D. S.; Sauerhoff, Mitchell W.; Saunders, Donald R.; "Carbon Disulfide", in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2000 doi: 10.1002/14356007.a05_185

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Worthing, Charles R.; Hance, Raymond J. (1991). The Pesticide Manual, A World Compendium (9th ed.). British Crop Protection Council. ISBN 9780948404429.

- "ATSDR - Public Health Statement: Carbon Disulfide". www.atsdr.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2018). The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History. London: John Murray. pp. 213–215. ISBN 978-1-4736-5903-2. OCLC 1057250632.

- "Occupational health and safety – chemical exposure". www.sbu.se. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- Lampadius (1796). "Etwas über flüssigen Schwefel, und Schwefel-Leberluft" [Something about liquid sulfur and liver-of-sulfur gas (i.e., hydrogen sulfide)]. Chemische Annalen für die Freunde der Naturlehre, Arzneygelährtheit, Haushaltungskunst und Manufacturen (Chemical Annals for the Friends of Science, Medicine, Economics, and Manufactures) (in German) (2): 136–137.

- Berzelius, J.; Marcet, Alexander (1813). "Experiments on the alcohol of sulphur, or sulphuret of carbon". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 103: 171–199.

- (Berzelius and Marcet, 1813), p. 187.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carbon disulfide. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Carbon Bisulphide. |

- Australian National Pollutant Inventory: Carbon disulfide

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Carbon Disulfide

- Inno Motion Engineering

- Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry Public Health Statement for Carbon Disulfide, 1996.

- Resources on Carbon Disulfide by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health