Shipibo language

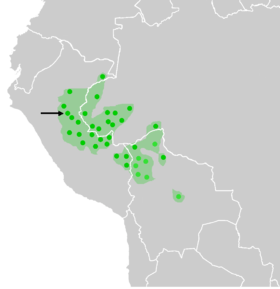

Shipibo (also Shipibo-Conibo, Shipibo-Konibo) is a Panoan language spoken in Peru and Brazil by approximately 26,000 speakers. Shipibo is an official language of Peru.

| Shipibo-Conibo | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Peru |

| Region | Ucayali Region |

| Ethnicity | Shipibo-Conibo people |

Native speakers | 26,000 (2003)[1] |

Panoan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:shp – Shipibo-Conibokaq – Tapiche Capanahua |

| Glottolog | ship1253[2] |

| |

Dialects

a.jpg)

A Shipibo jar

Shipibo has three attested dialects:

- Shipibo and Konibo (Conibo), which have merged

- Kapanawa of the Tapiche River, which is obsolescent

Extinct Xipináwa (Shipinawa) is thought to have been a dialect as well, but there is no linguistic data (Fleck 2013).

Phonology

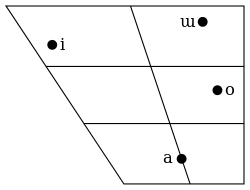

Vowels

| Front | Central | Near-back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ɯ̟ ɯ̟̃ u | ||

| Near-close | i̞ ĩ̞ i | ||

| Mid | e ẽ | o̽ o̽̃ o | |

| Near-open vowel | ɐ ɐ̃ a |

- /i̞/ is near-close front unrounded.[3]

- /ɯ̟/ is close near-back unrounded.[3]

- Before coronal consonants (especially /n, t, s/) it can be realized as close central unrounded [ɨ].[4]

- /o̽/ is mid near-back unrounded.[3]

- /i̞, ɯ̟, o̽/ tend to be more central in closed syllables.[4]

- /ɐ/ is near-open central unrounded.[3]

- In connected speech, two adjacent vowels may be realized as a rising diphthong.[4]

Nasal

- The oral vowels /ɯ̟, i̞, o̽, e, ɐ/ are phonetically nasalized [ɯ̟̃, ĩ̞, o̽̃, ẽ, ɐ̃] after a nasal consonant, but the phonological behaviour of these allophones is different from the nasal vowel phonemes /ɯ̟̃, ĩ̞, o̽̃, ẽ, ɐ̃/.[3]

- Oral vowels in syllables preceding syllables with nasal vowels are realized as nasal, but not when a consonant other than /w, j/ intervenes.[4]

Unstressed

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k c/qu | ʔ h | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts ts | tʃ ch | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s s | ʂ s̈h | ʃ sh | h j | ||

| voiced | β b | ||||||

| Approximant | w hu | ɻ r | j y | ||||

- /m, p, β/ are bilabial, whereas /w/ is labialized velar.

- /β/ is most typically a fricative [β], but other realizations (such as an approximant [β̞], a stop [b] and an affricate [bβ]) also appear. The stop realization is most likely to appear in word-initial stressed syllables, whereas the approximant realization appears most often as onsets to non-initial unstressed syllables.[3]

- /n, ts, s/ are alveolar [n, ts, s], whereas /t/ is dental [t̪].[5]

- The /ʂ–ʃ/ distinction can be described as an apical–laminal one.[3]

- /tʃ, ʃ/ are palato-alveolar, whereas /j/ is palatal.[5]

- Before nasal vowels, /w, j/ are nasalized [w̃, j̃] and may be even realized close to nasal stops [ŋʷ, ɲ].[4]

- /w/ is realized as [w] before /a, ã/, as [ɥ] before /i, ĩ/ and as [ɰ] before /ɯ, ɯ̃/. It does not occur before /o, õ/.[4]

- /ɻ/ is a very variable sound:

- Intervocalically, it is realized either as an approximant [ɻ], or sometimes as a (weak) fricative [ʐ].[3]

- Sometimes (especially in the beginning of a stressed syllable) it can be realized as a postalveolar affricate [d̠͡z̠], or a stop-appproximant sequence [d̠ɹ̠].[4]

- It can also be realized as a postalveolar flap [ɾ̠].[3]

References

- Shipibo-Conibo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Tapiche Capanahua at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Shipibo-Konibo–Kapanawa". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Valenzuela, Márquez Pinedo & Maddieson (2001), p. 282.

- Valenzuela, Márquez Pinedo & Maddieson (2001), p. 283.

- Valenzuela, Márquez Pinedo & Maddieson (2001), p. 281.

Bibliography

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Elias-Ulloa, Jose (2000). El Acento en Shipibo (Stress in Shipibo). Thesis. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima - Peru.

- Elias-Ulloa, Jose (2005). Theoretical Aspects of Panoan Metrical Phonology: Disyllabic Footing and Contextual Syllable Weight. Ph. D. Dissertation. Rutgers University. ROA 804 .

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70414-3.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

- Loriot, James and Barbara E. Hollenbach. 1970. "Shipibo paragraph structure." Foundations of Language 6: 43-66. (This was the seminal Discourse Analysis paper taught at SIL in 1956-7.)

- Loriot, James, Erwin Lauriault, and Dwight Day, compilers. 1993. Diccionario shipibo - castellano. Serie Lingüística Peruana, 31. Lima: Ministerio de Educación and Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. 554 p. (Spanish zip-file available online http://www.sil.org/americas/peru/show_work.asp?id=928474530143&Lang=eng) This has a complete grammar published in English by SIL only available through SIL.

- Valenzuela, Pilar M.; Márquez Pinedo, Luis; Maddieson, Ian (2001), "Shipibo", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 31 (2): 281–285, doi:10.1017/S0025100301002109

External links

| Shipibo test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shipibo-Conibo. |

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.