Received Pronunciation

Received Pronunciation (RP) is the accent traditionally regarded as the standard for British English. For over a century there has been argument over such issues as the definition of RP, whether it is geographically neutral, how many speakers there are, whether sub-varieties exist, how appropriate a choice it is as a standard and how the accent has changed over time.[1] RP is an accent, so the study of RP is concerned only with matters of pronunciation: other areas relevant to the study of language standards such as vocabulary, grammar and style are not considered.

History

The introduction of the term Received Pronunciation is usually credited to the British phonetician Daniel Jones. In the first edition of the English Pronouncing Dictionary (1917), he named the accent "Public School Pronunciation" ("public" being what Americans would term "private"), but for the second edition in 1926, he wrote, "In what follows I call it Received Pronunciation, for want of a better term."[2] However, the term had actually been used much earlier by P. S. Du Ponceau in 1818.[3] A similar term, received standard, was coined by Henry C. K. Wyld in 1927.[4] The early phonetician Alexander John Ellis used both terms interchangeably but with a much broader definition than Daniel Jones, having said "there is no such thing as a uniform educated pron. of English, and rp. and rs. is a variable quantity differing from individual to individual, although all its varieties are 'received', understood and mainly unnoticed".[5]

According to Fowler's Modern English Usage (1965), the correct term is "'the Received Pronunciation'. The word 'received' conveys its original meaning of 'accepted' or 'approved', as in 'received wisdom'."[6]

RP is often believed to be based on the accents of southern England, but it actually has most in common with the Early Modern English dialects of the East Midlands.[7] This was the most populated and most prosperous area of England during the 14th and 15th centuries. By the end of the 15th century, "Standard English" was established in the City of London.[8][9]

Alternative names

Some linguists have used the term "RP" while expressing reservations about its suitability.[10][11][12] The Cambridge-published English Pronouncing Dictionary (aimed at those learning English as a foreign language) uses the phrase "BBC Pronunciation" on the basis that the name "Received Pronunciation" is "archaic" and that BBC News presenters no longer suggest high social class and privilege to their listeners.[13] Other writers have also used the name "BBC Pronunciation".[14][15]

The phonetician Jack Windsor Lewis frequently criticises the name "Received Pronunciation" in his blog: he has called it "invidious",[16] a "ridiculously archaic, parochial and question-begging term"[17] and noted that American scholars find the term "quite curious".[18] He used the term "General British" (to parallel "General American") in his 1970s publication of A Concise Pronouncing Dictionary of American and British English[19] and in subsequent publications.[20] The name "General British" is adopted in the latest revision of Gimson's Pronunciation of English.[21] Beverley Collins and Inger Mees use the term "Non-Regional Pronunciation" for what is often otherwise called RP, and reserve the term "Received Pronunciation" for the "upper-class speech of the twentieth century".[22] Received Pronunciation has sometimes been called "Oxford English", as it used to be the accent of most members of the University of Oxford.[23] The Handbook of the International Phonetic Association uses the name "Standard Southern British". Page 4 reads:

Standard Southern British (where 'Standard' should not be taken as implying a value judgment of 'correctness') is the modern equivalent of what has been called 'Received Pronunciation' ('RP'). It is an accent of the south east of England which operates as a prestige norm there and (to varying degrees) in other parts of the British Isles and beyond.[24]

In her book Kipling's English History (1974) Marghanita Laski refers to this accent as "gentry". "What the Producer and I tried to do was to have each poem spoken in the dialect that was, so far as we could tell, ringing in Kipling's ears when he wrote it. Sometimes the dialect is most appropriately, Gentry. More often, it isn't."[25]

Sub-varieties

Faced with the difficulty of defining a single standard of RP, some researchers have tried to distinguish between different sub-varieties:

- Gimson (1980) proposed Conservative, General, and Advanced; "Conservative RP" referred to a traditional accent associated with older speakers with certain social backgrounds; General RP was considered neutral regarding age, occupation or lifestyle of the speaker; and Advanced RP referred to speech of a younger generation of speakers.[26] Later editions (e.g., Gimson 2008) use the terms General, Refined and Regional RP. In the latest revision of Gimson's book, the terms preferred are General British (GB), Conspicuous GB and Regional GB.[21]

- Wells (1982) refers to "mainstream RP" and "U-RP"; he suggests that Gimson's categories of Conservative and Advanced RP referred to the U-RP of the old and young respectively. However, Wells stated, "It is difficult to separate stereotype from reality" with U-RP.[27] Writing on his blog in February 2013, Wells wrote, "If only a very small percentage of English people speak RP, as Trudgill et al claim, then the percentage speaking U-RP is vanishingly small" and "If I were redoing it today, I think I'd drop all mention of 'U-RP'".[28]

- Upton distinguishes between RP (which he equates with Wells's "mainstream RP"), Traditional RP (after Ramsaran 1990), and an even older version which he identifies with Cruttenden's "Refined RP".[29]

- An article on the website of the British Library refers to Conservative, Mainstream and Contemporary RP.[30]

Characteristics and status of RP

Traditionally, Received Pronunciation has been associated with high social class. It was the "everyday speech in the families of Southern English persons whose men-folk [had] been educated at the great public boarding-schools"[31] and which conveyed no information about that speaker's region of origin before attending the school. An 1891 teacher’s handbook stated “It is the business of educated people to speak so that no-one may be able to tell in what county their childhood was passed”.[32] Nevertheless, in the 19th century some British prime ministers still spoke with some regional features, such as William Ewart Gladstone.[33]

Opinions differ over the proportion of British speakers who have RP as their accent. Trudgill estimated in 1974 that 3% of people in Britain were RP speakers,[34] but this rough estimate has been questioned by J. Windsor Lewis.[35] Upton notes higher estimates of 5% (Romaine, 2000) and 10% (Wells, 1982) but refers to all these as "guesstimates" that are not based on robust research.[36] A recent book with the title English after RP discusses "the rise and fall of RP" and describes "phonetic developments between RP and contemporary Standard Southern British (SSB)".[37]

The claim that RP is non-regional is disputed, since it is most commonly found in London and the south east of England. It is defined in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary as "the standard accent of English as spoken in the South of England",[38] and alternative names such as “Standard Southern British” have been used.[39] Despite RP’s historic high social prestige in Britain,[40] being seen as the accent of those with power, money, and influence, it may be perceived negatively by some as being associated with undeserved privilege[41][42] and as a symbol of the south-east's political power in Britain.[42] Based on a 1997 survey, Jane Stuart-Smith wrote, "RP has little status in Glasgow, and is regarded with hostility in some quarters".[43] A 2007 survey found that residents of Scotland and Northern Ireland tend to dislike RP.[44] It is shunned by some with left-wing political views, who may be proud of having an accent more typical of the working class.[45] Since the Second World War, and increasingly since the 1960s, a wider acceptance of regional English varieties has taken hold in education and public life.[46][47]

RP in use

Media

In the early days of British broadcasting, RP was almost universally used by speakers of English origin. In 1926 the BBC established an Advisory Committee on Spoken English with distinguished experts, including Daniel Jones, to advise on correct pronunciation and other aspects of broadcast language. This was not successful, and was dissolved in the Second World War.[48] An interesting departure from the use of RP was the BBC's use of Yorkshire-born Wilfred Pickles as a newsreader during the Second World War (to distinguish BBC broadcasts from German propaganda).[49][50] In recent years RP has played a much smaller role in broadcast speech. In fact, as Catherine Sangster points out, “there is not (and never was) an official BBC pronunciation standard”.[51] RP is most often heard in the speech of announcers and newsreaders on BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4, and some TV channels, but non-RP accents are now more widely accepted.[52]

It has been claimed that digital assistants such as Siri, Amazon Alexa or Google Assistant speak with an RP accent in their English versions.

Dictionaries

Most English dictionaries published in Britain (including the Oxford English Dictionary) now give phonetically transcribed RP pronunciations for all words. Pronunciation dictionaries represent a special class of dictionary giving a wide range of possible pronunciations: British pronunciation dictionaries are all based on RP, though not necessarily using that name. Daniel Jones transcribed RP pronunciations of words and names in the English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press continues to publish this title, as of 1997 edited by Peter Roach. Two other pronunciation dictionaries are in common use: the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary,[53] compiled by John C. Wells (using the name "Received Pronunciation"), and Clive Upton's Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English,[54] (now republished as The Routledge Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English).[55]

Language teaching

Pronunciation forms an essential component of language learning and teaching; a model accent in necessary for learners to aim at, and to act as a basis for description in textbooks and classroom materials. RP has been the traditional choice for teachers and learners of British English.[56] However, the choice of pronunciation model is difficult, and the adoption of RP is in many ways problematical.[57][58]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | r | j | w | ||||||||||

Nasals and liquids (/m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /r/, /l/) may be syllabic in unstressed syllables.[60] The consonant in 'row', 'arrow' in RP is generally a postalveolar approximant,[60] which would normally be expressed with the sign [ɹ] in the International Phonetic Alphabet, but the sign /r/ is nonetheless traditionally used for RP in most of the literature on the topic.

Voiceless plosives (/p/, /t/, /k/, /tʃ/) are aspirated at the beginning of a syllable, unless a completely unstressed vowel follows. (For example, the /p/ is aspirated in "impasse", with primary stress on "-passe", but not "compass", where "-pass" has no stress.) Aspiration does not occur when /s/ precedes in the same syllable, as in "spot" or "stop". When a sonorant /l/, /r/, /w/, or /j/ follows, this aspiration is indicated by partial devoicing of the sonorant.[61] /r/ is a fricative when devoiced.[60]

Syllable final /p/, /t/, /tʃ/, and /k/ may be either preceded by a glottal stop (glottal reinforcement) or, in the case of /t/, fully replaced by a glottal stop, especially before a syllabic nasal (bitten [ˈbɪʔn̩]).[61][62] The glottal stop may be realised as creaky voice; thus, an alternative phonetic transcription of attempt [əˈtʰemʔt] could be [əˈtʰemm̰t].[60]

As in other varieties of English, voiced plosives (/b/, /d/, /ɡ/, /dʒ/) are partly or even fully devoiced at utterance boundaries or adjacent to voiceless consonants. The voicing distinction between voiced and voiceless sounds is reinforced by a number of other differences, with the result that the two of consonants can clearly be distinguished even in the presence of devoicing of voiced sounds:

- Aspiration of voiceless consonants syllable-initially.

- Glottal reinforcement of /p, t, k, tʃ/ syllable-finally.

- Shortening of vowels before voiceless consonants.

As a result, some authors prefer to use the terms "fortis" and "lenis" in place of "voiceless" and "voiced". However, the latter are traditional and in more frequent usage.

The voiced dental fricative (/ð/) is more often a weak dental plosive; the sequence /nð/ is often realised as [n̪n̪] (a long dental nasal).[63][64][65] /l/ has velarised allophone ([ɫ]) in the syllable rhyme.[66] /h/ becomes voiced ([ɦ]) between voiced sounds.[67][68]

Vowels

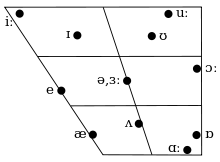

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ɪ | ʊ | |

| Mid | e | ə | ɒ |

| Open | æ | ʌ |

Examples of short vowels: /ɪ/ in kit, mirror and rabbit, /ʊ/ in foot and cook, /e/ in dress and merry, /ʌ/ in strut and curry, /æ/ in trap and marry, /ɒ/ in lot and orange, /ə/ in ago and sofa.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | iː | uː | ɔː ( |

| Mid | eə | ɜː | |

| Open | ɑː |

Examples of long vowels: /iː/ in fleece, /uː/ in goose, /eə/ in bear, /ɜː/ in nurse and furry, /ɔː/ in north, force and thought, /ɑː/ in father and start.

The long mid front vowel [ɛː] is transcribed with the traditional symbol ⟨eə⟩ in this article. The predominant realisation in contemporary RP is monophthongal.[71]

Long and short vowels

RP's long high vowels /iː/ and /uː/ are slightly diphthongised, and are often narrowly transcribed in phonetic literature as diphthongs [ɪi] and [ʊu].[72]

The terms "long" and "short" are relative to each other when applied to the vowel phonemes of RP. Vowels may be phonologically long or short (i.e. belong to the long or the short group of vowel phonemes) but their length is influenced by their context: in particular, they are shortened if a voiceless (fortis) consonant follows in the syllable, so that, for example, the vowel in 'bat' [bæʔt] is shorter than the vowel in 'bad' [bæd]. The process is known as pre-fortis clipping. Thus phonologically short vowels in one context can be phonetically longer than phonologically long vowels in another context.[60] For example, the phonologically long vowel /iː/ in 'reach' /riːtʃ/ (which ends with a voiceless consonant) may be shorter than the phonologically short vowel /ɪ/ in the word 'ridge' /rɪdʒ/ (which ends with a voiced consonant). Wiik,[73] cited in Cruttenden (2014), published durations of English vowels with a mean value of 17.2 csec. for short vowels before voiced consonants but a mean value of 16.5 csec for long vowels preceding voiceless consonants.[74]

In natural speech, the plosives /t/ and /d/ often have no audible release utterance-finally, and voiced consonants are partly or completely devoiced (as in [b̥æd̥]); thus the perceptual distinction between pairs of words such as 'bad' and 'bat', or 'seed' and 'seat' rests mostly on vowel length (though the presence or absence of glottal reinforcement provides an additional cue).[75]

In addition to such length distinctions, unstressed vowels are both shorter and more centralised than stressed ones. In unstressed syllables occurring before vowels and in final position, contrasts between long and short high vowels are neutralised and short [i] and [u] occur (e.g. happy [ˈhæpi], throughout [θɹuˈaʊʔt]).[76] The neutralisation is common throughout many English dialects, though the phonetic realisation of e.g. [i] rather than [ɪ] (a phenomenon called happy-tensing) is not as universal.

Unstressed vowels vary in quality:

- /i/ (as in HAPPY) ranges from close front [i] to close-mid retracted front [e̠];[77]

- /u/ (as in INFLUENCE) ranges from close advanced back [u̟] to close-mid retracted central [ɵ̠];[77] according to the phonetician Jane Setter, the typical pronunciation of this vowel is a weakly rounded, mid-centralized close back unrounded vowel, transcribed in the IPA as [u̜̽] or simply [ʊ̜];[78]

- /ə/ (as in COMMA) ranges from close-mid central [ɘ] to open-mid central [ɜ].[77]

Diphthongs and triphthongs

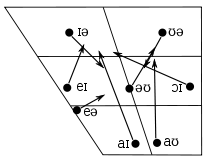

| Diphthong | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Closing | ||

| /eɪ/ ( | /beɪ/ | bay |

| /aɪ/ ( | /baɪ/ | buy |

| /ɔɪ/ ( | /bɔɪ/ | boy |

| /əʊ/ ( | /bəʊ/ | beau |

| /aʊ/ | /baʊ/ | bough |

| Centring | ||

| /ɪə/ | /bɪə/ | beer |

| /ʊə/ | /bʊə/ | boor |

| (formerly /ɔə/) | /bɔə/ | boar |

The centring diphthongs are gradually being eliminated in RP. The vowel /ɔə/ (as in "door", "boar") had largely merged with /ɔː/ by the Second World War, and the vowel /ʊə/ (as in "poor", "tour") has more recently merged with /ɔː/ as well among most speakers,[79] although the sound /ʊə/ is still found in conservative speakers. See poor–pour merger. The remaining centring glide /ɪə/ is increasingly pronounced as a monophthong [ɪː], although without merging with any existing vowels.[61]

The diphthong /əʊ/ is pronounced by some RP speakers in a noticeably different way when it occurs before /l/, if that consonant is syllable-final and not followed by a vowel (the context in which /l/ is pronounced as a "dark l"). The realization of /əʊ/ in this case begins with a more back, rounded and sometimes more open vowel quality; it may be transcribed as [ɔʊ] or [ɒʊ]. It is likely that the backness of the diphthong onset is the result of allophonic variation caused by the raising of the back of the tongue for the /l/. If the speaker has "l-vocalization" the /l/ is realized as a back rounded vowel, which again is likely to cause backing and rounding in a preceding vowel as coarticulation effects. This phenomenon has been discussed in several blogs by John C. Wells.[80][81][82] In the recording included in this article the phrase 'fold his cloak' contains examples of the /əʊ/ diphthong in the two different contexts. The onset of the pre-/l/ diphthong in 'fold' is slightly more back and rounded than that in 'cloak', though the allophonic transcription does not at present indicate this.

RP also possesses the triphthongs /aɪə/ as in tire, /aʊə/ as in tower, /əʊə/ as in lower, /eɪə/ as in layer and /ɔɪə/ as in loyal. There are different possible realisations of these items: in slow, careful speech they may be pronounced as a two-syllable triphthong with three distinct vowel qualities in succession, or as a monosyllabic triphthong. In more casual speech the middle vowel may be considerably reduced, by a process known as smoothing, and in an extreme form of this process the triphthong may even be reduced to a single vowel, though this is rare, and almost never found in the case of /ɔɪə/.[83] In such a case the difference between /aʊə/, /aɪə/, and /ɑː/ in tower, tire, and tar may be neutralised with all three units realised as [ɑː] or [äː]. This type of smoothing is known as the tower–tire, tower–tar and tire–tar mergers.

| As two syllables | Triphthong | Loss of mid-element | Further simplified as | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [aɪ.ə] | [aɪə] | [aːə] | [aː] | tire |

| [ɑʊ.ə] | [ɑʊə] | [ɑːə] | [ɑː] | tower |

| [əʊ.ə] | [əʊə] | [əːə] | [ɜː] | lower |

| [eɪ.ə] | [eɪə] | [ɛːə] | [ɛː] | layer |

| [ɔɪ.ə] | [ɔɪə] | [ɔːə] | [ɔː] | loyal |

BATH vowel

There are differing opinions as to whether /æ/ in the BATH lexical set can be considered RP. The pronunciations with /ɑː/ are invariably accepted as RP.[84] The English Pronouncing Dictionary does not admit /æ/ in BATH words and the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary lists them with a § marker of non-RP status.[85] John Wells wrote in a blog entry on 16 March 2012 that when growing up in the north of England he used /ɑː/ in "bath" and "glass", and considers this the only acceptable phoneme in RP.[86] Others have argued that /æ/ is too categorical in the north of England to be excluded. Clive Upton believes that /æ/ in these words must be considered within RP and has called the opposing view "south-centric".[87] Upton's Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English gives both variants for BATH words. A. F. Gupta's survey of mostly middle-class students found that /æ/ was used by almost everyone who was from clearly north of the isogloss for BATH words. She wrote, "There is no justification for the claims by Wells and Mugglestone that this is a sociolinguistic variable in the north, though it is a sociolinguistic variable on the areas on the border [the isogloss between north and south]".[88] In a study of speech in West Yorkshire, K. M. Petyt wrote that "the amount of /ɑː/ usage is too low to correlate meaningfully with the usual factors", having found only two speakers (both having attended boarding schools in the south) who consistently used /ɑː/.[89]

Jack Windsor Lewis has noted that the Oxford Dictionary's position has changed several times on whether to include short /æ/ within its prescribed pronunciation.[90] The BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names uses only /ɑː/, but its author, Graham Pointon, has stated on his blog that he finds both variants to be acceptable in place names.[91]

Some research has concluded that many people in the North of England have a dislike of the /ɑː/ vowel in BATH words. A. F. Gupta wrote, "Many of the northerners were noticeably hostile to /ɡrɑːs/, describing it as 'comical', 'snobbish', 'pompous' or even 'for morons'."[88] On the subject, K. M. Petyt wrote that several respondents "positively said that they did not prefer the long-vowel form or that they really detested it or even that it was incorrect".[92] Mark Newbrook has assigned this phenomenon the name "conscious rejection", and has cited the BATH vowel as "the main instance of conscious rejection of RP" in his research in West Wirral.[93]

French words

John Wells has argued that, as educated British speakers often attempt to pronounce French names in a French way, there is a case for including /ɒ̃/ (as in bon), and /æ̃/ and /ɜ̃:/ (as in vingt-et-un), as marginal members of the RP vowel system.[94] He also argues against including other French vowels on the grounds that very few British speakers succeed in distinguishing the vowels in bon and banc, or in rue and roue.[94]

Alternative notation

Not all reference sources use the same system of transcription. In particular:

- /æ/ as in trap is also written /a/.[95]

- /e/ as in dress is also written /ɛ/.[95][96]

- /ʌ/ as in cup is also written /ɐ/.[95]

- /ʊ/ as in foot is also written /ɵ/.[95]

- /ɜː/ as in nurse is also written /əː/.[95]

- /aɪ/ as in price is also written /ʌɪ/.[95]

- /aʊ/ as in mouse is also written /ɑʊ/[95]

- /eə/ as in square is also written /ɛə/, and is also sometimes treated as a long monophthong /ɛː/.[95]

- /eɪ/ as in face is also written /ɛɪ/.[95]

- /ɪə/ as in near is also written /ɪː/.[95]

- /əʊ/ before /l/ in a closed syllable as in goal is also written /ɔʊ/.[95]

- /uː/ as in goose is also written /ʉː/.[95]

Most of these variants are used in the transcription devised by Clive Upton for the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993) and now used in many other Oxford University Press dictionaries.

The linguist Geoff Lindsey has argued that the system of transcription for RP has become outdated and has proposed a new system as a replacement.[97][98]

Historical variation

Like all accents, RP has changed with time. For example, sound recordings and films from the first half of the 20th century demonstrate that it was usual for speakers of RP to pronounce the /æ/ sound, as in land, with a vowel close to [ɛ], so that land would sound similar to a present-day pronunciation of lend. RP is sometimes known as the Queen's English, but recordings show that even Queen Elizabeth II has changed her pronunciation over the past 50 years, no longer using an [ɛ]-like vowel in words like land.[99] The change in RP may be observed in the home of "BBC English". The BBC accent of the 1950s is distinctly different from today's: a news report from the 1950s is recognisable as such, and a mock-1950s BBC voice is used for comic effect in programmes wishing to satirise 1950s social attitudes such as the Harry Enfield Show and its "Mr. Cholmondeley-Warner" sketches.[100]

A few illustrative examples of changes in RP during the 20th century and early 21st are given below. A more comprehensive list (using the name 'General British' in place of 'RP') is given in Gimson's Pronunciation of English.[101]

Vowels and diphthongs

- Words such as CLOTH, gone, off, often, salt were pronounced with /ɔː/ instead of /ɒ/, so that often and orphan were homophones (see lot–cloth split). The Queen still uses the older pronunciations,[102] but it is now rare to hear this on the BBC.

- There used to be a distinction between horse and hoarse with an extra diphthong /ɔə/ appearing in words like hoarse, FORCE, and pour.[103] The symbols used by Wright are slightly different: the sound in fall, law, saw is transcribed as /oː/ and that in more, soar, etc. as /oə/. Daniel Jones gives an account of the /ɔə/ diphthong, but notes "many speakers of Received English (sic), myself among them, do not use the diphthong at all, but replace it always by /ɔː/".[104]

- The vowel in words such as tour, moor, sure used to be /ʊə/, but this has merged with /ɔː/ for many contemporary speakers. The effect of these two mergers (horse-hoarse and 'moor - 'more') is to bring about a number of three-way mergers of items which were hitherto distinct, such as poor, paw and pore (/pʊə/, /pɔː/, /pɔə/) all becoming /pɔː/.

- The DRESS vowel and the starting point of the FACE diphthong has become lowered from mid [e̞] to open-mid [ɛ].[105]

- Before the Second World War, the vowel of cup was a back vowel close to cardinal [ʌ] but has since shifted forward to a central position so that [ɐ] is more accurate; phonemic transcription of this vowel as /ʌ/ is still common largely for historical reasons.[106]

- There has been a change in the pronunciation of the unstressed final vowel of 'happy' as a result of a process known as happY-tensing: an older pronunciation of 'happy' would have had the vowel /ɪ/ whereas a more modern pronunciation has a vowel nearer to /iː/.[107] In pronunciation handbooks and dictionaries it is now common to use the symbol /i/ to cover both possibilities.

- In a number of words where contemporary RP has an unstressed syllable with schwa /ə/, older pronunciations had /ɪ/, for instance, the final vowel in the following: kindness, witness, toilet, fortunate.[108]

- The /ɛə/ phoneme (as in fair, care, there) was realized as a centring diphthong [ɛə] in the past, whereas many present-day speakers of RP pronounce it as a long monophthong [ɛː].[108]

- A change in the symbolization of the GOAT diphthong reflects a change in the pronunciation of the starting point: older accounts of this diphthong describe it as starting with a tongue position not far from cardinal [o], moving towards [u].[109] This was often symbolized as /ou/ or /oʊ/. In modern RP the starting point is unrounded and central, and is symbolized /əʊ/.[110]

- In a study of a group of speakers born between 1981 and 1993, it was observed that the vowel /ɒ/ had shifted upward, approaching [ɔ] in quality.[111]

- The vowels /ʊ/ and /uː/ have undergone fronting and reduction in the amount of lip-rounding[112] (phonetically, these can be transcribed [ʊ̜̈] and [ʉ̜ː], respectively).

- As noted above, /æ/ has become more open, near to cardinal [a].[113][114][110]

Consonants

- For speakers of Received Pronunciation in the late 19th century, it was common for the consonant combination ⟨wh⟩ (as in which, whistle, whether) to be realised as a voiceless labio-velar fricative /ʍ/ (also transcribed /hw/), as can still be heard in the 21st century in the speech of many speakers in Ireland, Scotland and parts of the USA. Since the beginning of the 20th century, however, the /ʍ/ phoneme has ceased to be a feature of RP, except in an exaggeratedly precise style of speaking.[115]

- There has been considerable growth in glottalization in RP, most commonly in the form of glottal reinforcement. This has been noted by writers on RP since quite early in the 20th century.[116] Ward notes pronunciations such as [nju:ʔtrəl] for neutral and [reʔkləs] for reckless. Glottalization of /tʃ/ is widespread in present-day RP when at the end of a stressed syllable, as in butcher [bʊʔtʃə].[117]

- The realization of /r/ as a tap or flap [ɾ] has largely disappeared from RP, though it can be heard in films and broadcasts from the first half of the 20th century. The word very was frequently pronounced [veɾɪ]. The same sound, however, is sometimes pronounced as an allophone of /t/ when it occurs intervocalically after a stressed syllable - the "flapped /t/" that is familiar in American English. Phonetically, this sounds more like /d/, and the pronunciation is sometimes known as /t/-voicing.[118]

Word-specific changes

A number of cases can be identified where changes in the pronunciation of individual words, or small groups of words, have taken place.

- The word Mass (referring to the religious ritual) was often pronounced /mɑːs/ in older versions of RP, but the word is now almost always /mæs/.

- A few words spelt with initial <h> used to be pronounced without the /h/ phoneme that is heard in present-day RP. Examples are hotel and historic: the older pronunciation required 'an' rather than 'a' as a preceding indefinite article, thus 'an hotel' /ən əʊtel/, 'an historic day' /ən ɪstɒrɪk deɪ/.

Comparison with other varieties of English

- Like most other varieties of English outside Northern England, RP has undergone the foot–strut split (pairs nut/put differ).[119]

- RP is a non-rhotic accent, so /r/ does not occur unless followed immediately by a vowel (pairs such as caught/court and formally/formerly are homophones, save that formerly may be said with a hint of /r/ to help to differentiate it, particularly where stressed for reasons of emphasising past status e.g. "He was FORMERLY in charge here.").[120]

- Unlike most North American accents of English, RP has not undergone the Mary–marry–merry, nearer–mirror, or hurry–furry mergers: all these words are distinct from each other.[121]

- Unlike many North American accents, RP has not undergone the father–bother or cot–caught mergers.

- RP does not have yod-dropping after /n/, /t/, /d/, /z/ and /θ/, but most speakers of RP variably or consistently yod-drop after /s/ and /l/ — new, tune, dune, resume and enthusiasm are pronounced /njuː/, /tjuːn/, /djuːn/, /rɪˈzjuːm/ and /ɪnˈθjuːziæzm/ rather than /nuː/, /tuːn/, /duːn/, /rɪˈzuːm/ and /ɪnˈθuːziæzm/. This contrasts with many East Anglian and East Midland varieties of English language in England and with many forms of American English, including General American. Hence also pursuit is commonly heard with /j/ and revolutionary less so but more commonly than evolution. For a subset of these, a yod has been lost over time: for example, in all of the words beginning suit, however the yod is sometimes deliberately reinserted in historical or stressed contexts such as "a suit in chancery" or "suitable for an aristocrat".

- The flapped variant of /t/ and /d/ (as in much of the West Country, Ulster, most North American varieties including General American, Australian English, and the Cape Coloured dialect of South Africa) is not used very often.

- RP has undergone wine–whine merger (so the sequence /hw/ is not present except among those who have acquired this distinction as the result of speech training).[122] The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, based in London, still teaches these two sounds for international breadth as distinct phonemes. They are also distinct from one another in most of Scotland and Ireland, in the northeast of England, and in the southeastern United States.[122]

- Unlike some other varieties of English language in England, there is no h-dropping in words like head or horse.[123] As shown in the spoken specimen below, in hurried phrases such as "as hard as he could" h-dropping commonly applies to the word he.

- Unlike most Southern Hemisphere English accents, RP has not undergone the weak-vowel merger, meaning that pairs such as Lenin/Lennon are distinct.[124]

- In traditional RP [ɾ] is an allophone of /r/ (it is used intervocalically, after /θ, ð/ and sometimes even after /b, ɡ/).[125][126]

Spoken specimen

The Journal of the International Phonetic Association regularly publishes "Illustrations of the IPA" which present an outline of the phonetics of a particular language or accent. It is usual to base the description on a recording of the traditional story of the North Wind and the Sun. There is an IPA illustration of British English (Received Pronunciation).

The speaker (female) is described as having been born in 1953, and educated at Oxford University. To accompany the recording there are three transcriptions: orthographic, phonemic and allophonic.

Phonemic

ðə ˈnɔːθ ˈwɪnd ən ðə ˈsʌn wə dɪˈspjuːtɪŋ ˈwɪtʃ wəz ðə ˈstrɒŋɡə, wen ə ˈtrævl̩ə ˌkeɪm əˌlɒŋ ˈræpt ɪn ə ˈwɔːm ˈkləʊk. ðeɪ əˈɡriːd ðət ðə ˈwʌn hu ˈfɜːst səkˈsiːdɪd ɪn ˈmeɪkɪŋ ðə ˈtrævlə ˌteɪk hɪz ˈkləʊk ɒf ʃʊd bi kənˌsɪdəd ˈstrɒŋɡə ðən ði ˈʌðə. ˈðen ðə ˌnɔːθ wɪnd ˈbluː əz ˈhɑːd əz i ˈkʊd, bət ðə ˈmɔː hi ˈbluː ðə ˌmɔː ˈkləʊsli dɪd ðə ˈtrævlə ˈfəʊld hɪz ˌkləʊk əˈraʊnd hɪm, ænd ət ˈlɑːst ðə ˈnɔ:θ wɪnd ˌɡeɪv ˈʌp ði əˈtempt. ˈðen ðə ˈsʌn ˌʃɒn aʊt ˈwɔːmli, ænd əˈmiːdiətli ðə ˈtrævlə ˈtʊk ɒf ɪz ˈkləʊk. n̩ ˌsəʊ ðə ˈnɔːθ ˈwɪn wəz əˈblaɪdʒd tʊ kənˈfes ðət ðə ˈsʌn wəz ðə ˈstrɒŋɡr̩ əv ðə ˈtuː.

Allophonic

ðə ˈnɔːθ ˈw̥ɪnd ən̪n̪ə ˈsʌn wə dɪˈspj̊u̟ːtɪŋ ˈwɪʔtʃ wəz ðə ˈstɹ̥ɒŋɡə, wen ə ˈtɹ̥ævl̩ə ˌkʰeɪm əˌlɒŋ ˈɹæptʰ ɪn ə ˈwɔːm ˈkl̥əʊkˣ. ðeɪ əˈɡɹ̥iːd̥ ð̥əʔ ðə ˈwʌn ɦu ˈfɜːs səkˈsiːdɪd ɪmˈmeɪxɪŋ ðə ˈtɹ̥ævlə ˌtʰeɪk̟x̟ɪs ˈkl̥əʊk ɒf ʃʊbbi kʰənˌsɪdəd̥ ˈstɹɒŋɡə ð̥ən̪n̪i ˈʌðə. ˈðen̪n̪ə ˌnɔːθ w̥ɪnd ˈbluː əz̥ ˈhɑːd̥ əs i ˈkʊd, bət̬ ð̥ə ˈmɔː hi ˈblu̟ː ðə ˌmɔ ˈkl̥əʊsl̥i d̥ɨd ð̥ə ˈtɹ̥æv̥lə ˈfəʊld̥ hɪz̥ ˌkl̥əʊkʰ əˈɹaʊnd hɪm, ænd ət ˈl̥ɑːst ð̥ə ˈnɔ:θ w̥ɪnd ˌɡ̊eɪv̥ ˈʌp ði̥ əˈtʰemʔt. ˈðen̪n̪ə ˈsʌn ˌʃɒn aʊt ˈwɔːmli, ænd əˈmiːdiətl̥i ð̥ə ˈtɹ̥ævlə ˈtʰʊk ɒf ɪz̥ ˈkl̥əʊkˣ. n̩ ˌsəʊ ðə ˈnɔːθ ˈw̥ɪn wəz̥ əˈblaɪdʒ̊ tʰɵ kʰənˈfes ð̥əʔ ð̥ə ˈsʌn wəz̥z̥ə ˈstɹ̥ɒŋɡɹ̩ əv̥ ð̥ə ˈtʰu̟ː.

Orthographic

The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveller came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveller take his cloak off should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could, but the more he blew the more closely did the traveller fold his cloak around him, and at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shone out warmly, and immediately the traveller took off his cloak. And so the North Wind was obliged to confess that the Sun was the stronger of the two.[127]

Notable speakers

The following people have been described as RP speakers:

- David Attenborough, broadcaster and naturalist[128]

- The British Royal Family[129][130]

- David Cameron, former Prime Minister of the UK (2010–2016)[131]

- Deborah Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, aristocrat and writer[132]

- Judi Dench, actress[133]

- Rupert Everett, actor[134]

- Lady Antonia Fraser, author and historian[132]

- Christopher Hitchens, late author and journalist[135]

- Boris Johnson, Prime Minister of the UK (2019–present)[134]

- Vanessa Kirby, actress[133]

- Helen Mirren, actress[136]

- Carey Mulligan, actress[133]

- Jeremy Paxman, broadcaster and TV presenter[132]

- Brian Sewell, art critic[137]

- Ed Stourton, broadcaster and journalist[138]

- Margaret Thatcher, former Prime Minister of the UK (1979–1990)[139]

- Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury (2002–2012)[129]

- Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury (2013–present)[129]

See also

- Accent (dialect)

- Accents (psychology)

- English language in the United Kingdom

- English language spelling reform

- General American

- Mid-Atlantic accent

- Linguistic prescription

- Prestige (sociolinguistics)

- U and non-U English

Notes and references

- Gimson, A.C., ed Cruttenden (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Routledge. pp. 74–81. ISBN 978-1-4441-8309-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Jones (1926), p. ix.

- DuPonceau (1818), p. 259.

- Wyld (1927), p. 23.

- Ellis (1869), p. 3.

- "Regional Voices – Received Pronunciation". British Library.

- Robinson, Jonnie. "Received Pronunciation". British Library. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Crystal (2003), pp. 54–55.

- Crystal (2005), pp. 243–244.

- Cruttenden (2008), pp. 77–80.

- Jenkins (2000), pp. 13–16.

- Wells (1982), p. 117.

- Jones (2011), p. vi.

- Ladefoged (2004).

- Trudgill (1999).

- Jack Windsor Lewis. "Review of the Daniel Jones English Pronouncing Dictionary 15th edition 1997". Yek.me.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Jack Windsor Lewis. "Ovvissly not one of us – Review of the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary". Yek.me.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Jack Windsor Lewis (19 February 1972). "British non-dialectal accents". Yek.me.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Windsor Lewis, Jack (1972). A Concise Pronouncing Dictionary of British and American English. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-431123-6.

- Jack Windsor Lewis. "Review of CPD in ELTJ". Yek.me.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Gimson, A.C., ed A. Cruttenden (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Routledge. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-1-4441-8309-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Collins & Mees (2003), pp. 3–4.

- Robinson, Jonnie (24 April 2019). "Received Pronunciation". The British Library. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. 4.

- Laski, M., comp. (1974) Kipling's English History. London: BBC; pp. 7, 12 &c.

- Schmitt (2007), p. 323.

- Wells (1982).

- exotic spices, John Wells's phonetic blog, 28 February 2013

- Bernd Kortmann (2004). Handbook of Varieties of English: Phonology; Morphology, Syntax - edit edition. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 217–230. ISBN 978-3110175325. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- British Library. "Sounds Familiar". Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Jones (1917), p. viii.

- Burrell, A. (1891). Recitation: a Handbook for Teachers in Public Elementary School. London.

- Gladstone's speech was the subject of a book The Best English. A claim for the superiority of Received Standard English, together with notes on Mr. Gladstone's pronunciation, H.C. Kennedy, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1934.

- Trudgill, Peter (8 December 2000). "Sociolinguistics of Modern RP". University College London. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Windsor Lewis, Jack. "A Notorious Estimate". JWL's Blogs. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Upton, Clive (21 January 2019). "Chapter 14: British English". In Reed, Marnie; Levis, John (eds.). The Handbook of English Pronunciation. John Wiley & Son. p. 251. ISBN 978-1119055266.

- Lindsey, Geoff (2019). English after RP: Standard British Pronunciation Today. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3030043568.

- Pearsall (1999), p. xiv.

- International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the IPA. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521637510.

- Hudson (1981), p. 337.

- Crystal, David (March 2007). "Language and Time". BBC voices. BBC. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- McArthur (2002), p. 43.

- Stuart-Smith, Jane (1999). "Glasgow: accent and voice quality". In Foulkes, Paul; Docherty, Gerard (eds.). Urban Voices. Arnold. p. 204. ISBN 0340706082.

- "Scottish and Irish accents top list of favourites". The Independent. 13 May 2007.

- McArthur (2002), p. 49.

- Fishman (1977), p. 319.

- Gimson, A.C., ed. Cruttenden (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4441-8309-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schwyter, J.R. 'Dictating to the Mob: The History of the BBC Advisory Committee on Spoken English', 2016, Oxford University Press, URL https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198736738.001.0001/acprof-9780198736738

- Discussed in Mugglestone (2003, pp. 277–278) but even then Pickles modified his speech towards RP when reading the news.

- Zoe Thornton, The Pickles Experiment – a Yorkshire man reading the news, Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society 2012, pp. 4–19.

- Sangster, Catherine, 'The BBC, its Pronunciation Unit and 'BBC English' in Roach, P., Setter, J. and Esling, J. (eds) Daniel Jones' English Pronouncing Dictionary, 4th Edition, Cambridge University Press, pp. xxviii-xxix

- Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (2011). Daniel Jones' English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge. p. xii.

- Wells, J C (2008). The Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Upton, Kretzschmar & Konopka (2001).

- Upton, Clive; Kretzschmar, William (2017). The Routledge Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English. Routledge. ISBN 9781138125667.

- "Case Studies – Received Pronunciation". British Library. 13 March 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

As well as being a living accent, RP is also a theoretical linguistic concept. It is the accent on which phonemic transcriptions in dictionaries are based, and it is widely used (in competition with General American) for teaching English as a foreign language.

- Brown, Adam (1991). Pronunciation Models. Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971-69-157-4.

- Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English. Routledge. pp. 325–352. ISBN 978-1-4441-8309-2.

- Roach (2004), pp. 240–241.

- Roach (2004), p. 241.

- Roach (2004), p. 240.

- Gimson (1970).

- Lodge (2009), pp. 148–49.

- Shockey (2003), pp. 43–44.

- Roach (2009), p. 112.

- Halle & Mohanan (1985), p. 65.

- Jones (1967), p. 201.

- Cruttenden (2008), p. 204.

- Collins & Mees (2003:95, 101)

- Collins & Mees (2003:92)

- Gimson (2014), p. 118.

- Roach (2009), p. 24.

- Wiik (1965).

- Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 9781444183092.

- Cruttenden, Alan (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 9781444183092.

- Roach (2004), pp. 241, 243.

- Wells (2008:XXV)

- "A World of Englishes: Is /ə/ "real"?". Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- Roca & Johnson (1999), p. 200.

- Wells, John. "Blog July 2006". Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Wells, John. "Blog July 2009". Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Wells, John. "Blog Nov 2009". Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Roach (2009), pp. 18–19.

- Wells (1982), pp. 203 ff.

- Jack Windsor Lewis (1990). "Review of Longman Pronunciation Dictionary". The Times.

- Wells, John (16 March 2012). "English places". John Wells's phonetic blog.

- Upton (2004), pp. 222–223.

- Gupta (2005), p. 25.

- Petyt (1985), pp. 166–167.

- Point 18 in Jack Windsor Lewis. "The General Central Northern Non-Dialectal Pronunciation of England". Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Pointon, Graham (20 April 2010). "Olivia O'Leary". Linguism: Language in a word.

- Petyt (1985), p. 286.

- Newbrook (1999), p. 101.

- Wells (2008), p. xxix.

- "Case Studies – Received Pronunciation Phonology – RP Vowel Sounds". British Library.

- Schmitt (2007), pp. 322–323.

- Lindsey, Geoff (8 March 2012). "The British English vowel system". speech talk.

- Wells, John (12 March 2012). "the Lindsey system". John Wells's phonetic blog.

- Language Log (5 December 2006). "Happy-tensing and coal in sex".

- Enfield, Harry. "Mr Cholmondeley-Warner on Life in the 1990's". Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Gimson, A.C., ed. A. Cruttenden (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Routledge. pp. 83–5. ISBN 978-1-4441-8309-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- The Queen's speech to President Sarkozy, "often" pronounced at 4:44.

- Wright (1905), p. 5, §12

- Jones, Daniel (1967). An outline of English phonetics (9th ed.). Heffer. p. 115, para 458. ISBN 978-0521210980.

- Lindsey, Geoff (3 June 2012). "Funny old vowels". Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Roca & Johnson (1999), pp. 135, 186.

- Trudgill (1999), p. 62.

- Robinson, Jonnie (24 April 2019). "Received Pronunciation". The British Library. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Jones, Daniel (1957). An outline of English phonetics (9th ed.). Heffer. p. 101, para 394. ISBN 978-0521210980.

- Wells, John (27 January 1994). "Whatever happened to Received Pronunciation?". Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Wikström (2013), p. 45. "It seems to be the case that younger RP or near-RP speakers typically use a closer quality, possibly approaching Cardinal 6 considering that the quality appears to be roughly intermediate between that used by older speakers for the LOT vowel and that used for the THOUGHT vowel, while older speakers use a more open quality, between Cardinal Vowels 13 and 6."

- Collins & Mees (2013), p. 207.

- de Jong et al. (2007), pp. 1814–1815.

- Roach (2011).

- Wells, John (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge University Press. pp. 228–9. ISBN 0 521 297192.

- Ward, Ida (1939). The Phonetics of English (3rd ed.). pp. 135–6, para 250.

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger (2019). Practical English Phonetics and Phonology (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-138-59150-9.

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger (2019). Practical English Phonetics and Phonology (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-138-59150-9.

- Wells (1982), pp. 196 ff.

- Wells (1982), p. 76.

- Wells (1982), p. 245.

- Wells (1982), pp. 228 ff.

- Wells (1982), pp. 253 ff.

- Wells (1982), pp. 167 ff.

- Wise (1957).

- Cruttenden (2008), pp. 221.

- Roach (2004).

- Wells, John (8 November 2010). "David Attenborough". John Wells's phonetic blog.

- Wells, John (3 May 2011). "the evidence of the vows". John Wells's phonetic blog.

- Wells, John (11 July 2007). "Any young U-RP speakers?".

- Wells, John (8 April 2010). "EE, yet again". John Wells's phonetic blog.

- Woods, Vicki (5 August 2011). "When I didn't know owt about posh speak". The Daily Telegraph.

- Lawson, Lindsey (14 October 2013). "A popular British accent with very few native speakers". The Voice Cafe. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Wells, John (12 June 2008). "RP back in fashion?".

- "British Accents". dialectblog.com. 25 January 2011.

- Klaus J. Kohler (2017) "Communicative Functions and Linguistic Forms in Speech Interaction", published by CUP (page 268)

- "The perils of talking posh". Evening Standard. 6 November 2001. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Cooper, Glenda (4 October 2014). "A 'posh' RP voice can break down barriers". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Has Beckham started talking posh?". BBC News.

Bibliography

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2003) [First published 1981], The Phonetics of English and Dutch (5th ed.), Leiden: Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004103406

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger (2013) [First published 2003], Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students (3rd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-50650-2

- Cruttenden, Alan, ed. (2008), Gimson's Pronunciation of English (7th ed.), London: Hodder, ISBN 978-0340958773

- Crystal, David (2003), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (2 ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-53033-4

- Crystal, David (2005), The Stories of English, Penguin

- DuPonceau, Peter S. (1818), "English phonology; or, An essay towards an analysis and description of the component sounds of the English language.", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 1, pp. 259–264

- Ellis, Alexander J. (1869), On early English pronunciation, New York, (1968): Greenwood PressCS1 maint: location (link)

- Elmes, Simon (2005), Talking for Britain: A journey through the voices of our nation, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-051562-3

- Fishman, Joshua (1977), ""Standard" versus "Dialect" in Bilingual Education: An Old Problem in a New Context", The Modern Language Journal, 61 (7): 315–325, doi:10.2307/324550, JSTOR 324550

- Gimson, Alfred C. (1970), An Introduction to the pronunciation of English, London: Edward Arnold

- Gimson, Alfred C. (1980), Pronunciation of English (3rd ed.)

- Gimson, Alfred Charles (2014), Cruttenden, Alan (ed.), Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.), Routledge, ISBN 9781444183092

- Gupta, Anthea Fraser (2005), "Baths and becks" (PDF), English Today, 21 (1): 21–27, doi:10.1017/S0266078405001069, ISSN 0266-0784

- Halle, Morris; Mohanan, K. P. (1985), "Segmental Phonology of Modern English", Linguistic Inquiry, The MIT Press, 16 (1): 57–116, JSTOR 4178420

- Hudson, Richard (1981), "Some Issues on Which Linguists Can Agree", Journal of Linguistics, 17 (2): 333–343, doi:10.1017/S0022226700007052

- International Phonetic Association (1999), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521637510

- Jenkins, Jennifer (2000), The Phonology of English as an International Language, Oxford

- Jones, Daniel (1917), English Pronouncing Dictionary (1st ed.), London: Dent

- Jones, Daniel (1926), English Pronouncing Dictionary (2nd ed.)

- Jones, Daniel (1967), An Outline of English Phonetics (9th ed.), Heffer

- Jones, Daniel (2011), Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18 ed.), Cambridge University Press

- de Jong, Gea; McDougall, Kirsty; Hudson, Toby; Nolan, Francis (2007), "The speaker discriminating power of sounds undergoing historical change: A formant-based study", the Proceedings of ICPhS Saarbrücken, pp. 1813–1816

- Ladefoged, Peter (2004), Vowels and Consonants, Thomson

- Lodge, Ken (2009), A Critical Introduction to Phonetics, Continuum

- McArthur, Tom (2002), The Oxford Guide to World English, Oxford University Press

- McDavid, Raven I. (1965), "American Social Dialects", College English, 26 (4): 254–260, doi:10.2307/373636, JSTOR 373636

- Mugglestone, Lynda (2003), 'Talking Proper': The Rise of Accent as Social Symbol (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press

- Newbrook, Mark (1999), "West Wirral: norms, self-reports and usage", in Foulkes, Paul; Docherty, Gerald J. (eds.), Urban Voices, pp. 90–106

- Pearce, Michael (2007), The Routledge Dictionary of English Language Studies, Routledge

- Pearsall, Judy, ed. (1999), The Concise Oxford English Dictionary (10th ed.)

- Petyt, K. M. (1985), Dialect and Accent in Industrial West Yorkshire, John Benjamins Publishing

- Ramsaran, Susan (1990), "RP: fact and fiction", Studies in the Pronunciation of English: A commemorative volume in honour of A. C. Gimson, Routledge, pp. 178–190

- Roach, Peter (2004), "British English: Received Pronunciation" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 34 (2): 239–245, doi:10.1017/S0025100304001768

- Roach, Peter (2009), English Phonetics and Phonology (4th ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-40718-2

- Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521152532

- Roca, Iggy; Johnson, Wyn (1999), A Course in Phonology, Blackwell Publishing

- Rogaliński, Paweł (2011), British Accents: Cockney, RP, Estuary English, Łódź, ISBN 978-83-272-3282-3

- Schmitt, Holger (2007), "The case for the epsilon symbol (ɛ) in RP DRESS", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (3): 321–328, doi:10.1017/S0025100307003131

- Shockey, Linda (2003), Sound Patterns of Spoken English, Blackwell

- Trudgill, Peter (1999), The Dialects of England, Blackwell

- Upton, Clive (2004), "Received Pronunciation", A Handbook of Varieties of English, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 217–230

- Upton, Clive; Kretzschmar, William A.; Konopka, Rafal (2001), Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Wells, John C. (1970), "Local accents in England and Wales", Journal of Linguistics, 6 (2): 231–252, doi:10.1017/S0022226700002632

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English I: An Introduction, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29719-2

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- Wiik, K. (1965), Finnish and English Vowels, B, 94, Annales Universitatis Turkensis

- Wikström, Jussi (2013), "An acoustic study of the RP English LOT and THOUGHT vowels", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 37–47, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000345

- Wise, Claude Merton (1957), Introduction to phonetics, Englewood Cliffs

- Wright, Joseph (1905), English Dialect Grammar

- Wyld, Henry C. K. (1927), A short history of English (3rd ed.), London: Murray

External links

- BBC page on Upper RP as spoken by the English upper-classes

- Sounds Familiar? – Listen to examples of received pronunciation on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website

- 'Hover & Hear' R.P., and compare it with other accents from the UK and around the World.

- Whatever happened to Received Pronunciation? – An article by the phonetician J. C. Wells about received pronunciation

Sources of regular comment on RP

- John Wells's phonetic blog

- Jack Windsor Lewis's PhonetiBlog

- Linguism – Language in a word, blog by Graham Pointon of the BBC Pronunciation Unit

Audio files