Korean phonology

This article is a technical description of the phonetics and phonology of Korean. Unless otherwise noted, statements in this article refer to South Korean standard language based on the Seoul dialect.

Morphophonemes are written inside vertical pipes (| |), phonemes inside slashes (/ /), and allophones inside brackets ([ ]).

Consonants

Korean has 19 consonant phonemes.[1]

For each stop and affricate, there is a three-way contrast between unvoiced segments, which are distinguished as plain, tense, and aspirated.

- The "plain" segments, sometimes referred to as "lax" or "lenis," are considered to be the more "basic" or unmarked members of the Korean obstruent series. The "plain" segments are also distinguished from the tense and aspirated phonemes by changes in vowel quality, including a relatively lower pitch of the following vowel.[2]

- The "tense" segments, also referred to as "fortis," "hard," or "glottalized," have eluded precise description and have been the subject of considerable phonetic investigation. In the Korean alphabet as well as all widely used romanization systems for Korean, they are represented as doubled plain segments: ㅃ pp, ㄸ tt, ㅉ jj, ㄲ kk. As it was suggested from the Middle Korean spelling, the tense consonants came from the initial consonant clusters sC-, pC-, psC-.[3][4]:29, 38, 452

- The "aspirated" segments are characterized by aspiration, a burst of air accompanied by the delayed onset of voicing.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal/Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ㅁ | n ㄴ | ŋ ㅇ | |||

| Stop and affricate |

plain | p ㅂ | t ㄷ | tɕ, ts ㅈ | k ㄱ | |

| tense | p͈ ㅃ | t͈ ㄸ | t͈ɕ, t͈s ㅉ | k͈ ㄲ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ ㅍ | tʰ ㅌ | tɕʰ, tsʰ ㅊ | kʰ ㅋ | ||

| Fricative | plain/aspirated | s ㅅ | h ㅎ | |||

| tense | s͈ ㅆ | |||||

| Liquid | l~ɾ ㄹ | |||||

| Approximant | w | j | ɰ | |||

| IPA | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| /p/ | 불 bul | [pul] | 'fire' or 'light' |

| /p͈/ | 뿔 ppul | [p͈ul] | 'horn' |

| /pʰ/ | 풀 pul | [pʰul] | 'grass' or 'glue' |

| /m/ | 물 mul | [m͊ul] | 'water' or 'liquid' |

| /t/ | 달 dal | [tal] | 'moon' or 'month' |

| /t͈/ | 딸 ttal | [t͈al] | 'daughter' |

| /tʰ/ | 탈 tal | [tʰal] | 'mask' or 'trouble' |

| /n/ | 날 nal | [n͊al] | 'day' or 'blade' |

| /tɕ/ | 자다 jada | [tɕada] | 'to sleep' |

| /t͈ɕ/ | 짜다 jjada | [t͈ɕada] | 'to squeeze' or 'to be salty' |

| /tɕʰ/ | 차다 chada | [tɕʰada] | 'to kick' or 'to be cold' |

| /k/ | 기 gi | [ki] | 'energy' |

| /k͈/ | 끼 kki | [k͈i] | 'talent' or 'meal' |

| /kʰ/ | 키 ki | [kʰi] | 'height' |

| /ŋ/ | 방 bang | [paŋ] | 'room' |

| /s/ | 살 sal | [sal] | 'flesh' |

| /s͈/ | 쌀 ssal | [s͈al] | 'uncooked grains of rice' |

| /ɾ/ | 바람 baram | [paɾam] | 'wind' or 'wish' |

| /l/ | 발 bal | [pal] | 'foot' |

| /h/ | 하다 hada | [hada] | 'to do' |

Notes

- 1.^ ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅉ are pronounced [tɕ, tɕʰ, t͈ɕ] in Seoul, but typically pronounced [ts, tsʰ, t͈s] in Pyongyang. Similarly, /s, s͈/ are palatalized as [ɕ, ɕ͈] before /i, j/ in Seoul. In Pyongyang they remain unchanged.

- 2.^ /m, n/ tend to be denasalized word-initially. /ŋ/ and /l/ cannot occur word-initially in native words.[5]

- 3.^ /p, t, tɕ, k/ are voiced [b, d, dʑ, ɡ] between voiced sounds but voiceless elsewhere. Among younger generations, they may be just as aspirated as /pʰ, tʰ, tɕʰ, kʰ/ in initial position; the primary difference is that vowels following the plain consonants carry low tone.[6][7] /pʰ, tʰ, tɕʰ, kʰ/ are strongly aspirated, more so than English voiceless stops. The affricates /tɕ͈, tɕʰ, tɕ/ may be pronounced as alveolar ([ts͈, tsʰ, ts~dz] by some speakers, especially before back vowels.

- 4.^ The IPA diacritic ⟨◌͈⟩, resembling a subscript double straight quotation mark, shown here with a placeholder circle, is used to denote the tensed consonants /p͈/, /t͈/, /k͈/, /t͈ɕ/, /s͈/.[lower-alpha 1] Its official use in the Extensions to the IPA is for strong articulation, but is used in literature for faucalized voice. The Korean consonants also have elements of stiff voice, but it is not yet known how typical that is of faucalized consonants. They are produced with a partially constricted glottis and additional subglottal pressure in addition to tense vocal tract walls, laryngeal lowering, or other expansion of the larynx.

An alternative analysis[8] proposes that the "tensed" series of sounds are (fundamentally) regular voiceless, unaspirated consonants: the "lax" sounds are voiced consonants that become devoiced initially, and the primary distinguishing feature between word-initial "lax" and "tensed" consonants is that initial lax sounds cause the following vowel to assume a low-to-high pitch contour, a feature reportedly associated with voiced consonants in many Asian languages, whereas tensed (and also aspirated) consonants are associated with a uniformly high pitch. - 5.^ The analysis of /s/ as phonologically plain or aspirated has been a source of controversy in the literature.[9] Its characteristics are nearest to those of plain stops, as it generally undergoes intervocalic voicing word-medially.[2] It shows moderate aspiration word-initially (in the same way "plain" stops /p/, /t/, /k/ do), but no aspiration word-medially.[2]

- 6.^ Between vowels, /h/ may either be voiced to [ɦ] or deleted.

- 7.^ /l/ is an alveolar flap [ɾ] between vowels or between a vowel and an /h/; it is [l] or [ɭ] at the end of a word, before a consonant other than /h/, or next to another /l/. There is free variation at the beginning of a word, where this phoneme tends to become [n] before most vowels and silent before /i, j/, but it is commonly [ɾ] in English loanwords.

- 8.^ When pronounced as an alveolar flap [ɾ], ㄹ is sometimes allophonic with [d], which generally does not occur elsewhere.

Positional allophones

Korean consonants have three principal positional allophones: initial, medial (voiced), and final (checked). The initial form is found at the beginning of phonological words. The medial form is found in voiced environments, intervocalically and after a voiced consonant such as n or l. The final form is found in checked environments such as at the end of a phonological word or before an obstruent consonant such as t or k. Nasal consonants (m, n, ng) do not have noticeable positional allophones beyond initial denasalization, and ng cannot appear in this position.

The table below is out of alphabetical order to make the relationships between the consonants explicit:

| Phoneme | ㄱ g |

ㅋ k |

ㄲ kk |

ㅇ ng |

ㄷ d |

ㅌ t |

ㅅ s |

ㅆ ss |

ㅈ j |

ㅊ ch |

ㄸ tt |

ㅉ jj |

ㄴ n |

ㄹ r |

ㅂ b |

ㅍ p |

ㅃ pp |

ㅁ m |

ㅎ h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial allophone | k~kʰ | kʰ | k͈ | n/a | t~tʰ | tʰ | s | s͈ | tɕ~tɕʰ | tɕʰ | t͈ | t͈ɕ | n~n͊ | ɾ, n~n͊ | p~pʰ | pʰː | p͈ | m~m͊ | h |

| Medial allophone | ɡ | ŋ | d | s~z | dʑ | n | ɾ | b | m | h~ɦ~n/a | |||||||||

| Final allophone | k̚ | t̚ | n/a | l | p̚ | n/a | n/a | ||||||||||||

All obstruents (stops, affricates, fricatives) become stops with no audible release at the end of a word: all coronals collapse to [t̚], all labials to [p̚], and all velars to [k̚].[lower-alpha 2] Final ㄹ r is a lateral [l] or [ɭ].

ㅎ h does not occur in final position,[lower-alpha 3] though it does occur at the end of non-final syllables, where it affects the following consonant. (See below.) Intervocalically, it is realized as voiced [ɦ], and after voiced consonants it is either [ɦ] or silent.

ㅇ ng does not occur in initial position, reflected in the way the hangeul jamo ㅇ has a different pronunciation in the initial position to the final position. These were distinguished when hangeul was created, with the jamo ㆁ with the upper dot and the jamo ㅇ without the upper dot; these were then conflated and merged in the standards for both the North Korean and South Korean standards.

In native Korean words, ㄹ r does not occur word initially, unlike in Chinese loans (Sino-Korean vocabulary). In South Korea, it is silent in initial position before /i/ and /j/, pronounced [n] before other vowels, and pronounced [ɾ] only in compound words after a vowel. The prohibition on word-initial r is called the "initial law" or dueum beopchik (두음법칙). Initial r is officially pronounced [ɾ] in North Korea. In both countries, initial r in words of foreign origin other than Chinese is pronounced [ɾ].

- "labour" (勞動) – North Korea: rodong (로동), South Korea: nodong (노동)

- "history" (歷史) – North Korea: ryŏksa (력사), South Korea: yeoksa (역사)

This rule also extends to ㄴ n in many native and all Sino-Korean words, which is also lost before initial /i/ and /j/ in South Korean; again, North Korean preserves the [n] phoneme there.

- "female" (女子) – North Korea: nyŏja (녀자), South Korea: yeoja (여자)

Vowels

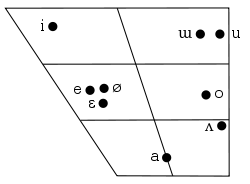

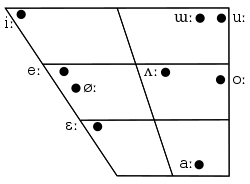

Korean has eight vowel phonemes and a length distinction for each. Long vowels are pronounced somewhat more peripherally than short ones. Two more vowels, the mid front rounded vowel ([ø] ㅚ) and the close front rounded vowel ([y] ㅟ),[11]:6 can still be heard in the speech of some older speakers, but they have been largely replaced by the diphthongs [we] and [ɥi], respectively.[4]:4–6 In a 2003 survey of 350 speakers from Seoul, nearly 90% pronounced the vowel ㅟ as [ɥi].[12]

In 2012, vowel length is reported almost completely neutralized in Korean, except for a very few older speakers of Seoul dialect,[13] for whom the distinctive vowel-length distinction is maintained only in the first syllable of a word.[12]

The distinction between /e/ and /ɛ/ is lost in South Korean dialects but robust in North Korean dialects.[14][15] For the speakers who do not make the difference, [e̞] seems to be the dominant form.[4]:4–6 For most of the speakers who still utilize vowel length contrastively, long /ʌː/ is actually [ɘː].[10] In Seoul Korean, /o/ is produced higher than /ʌ/, while in Pyongan, /o/ is lower than /ʌ/.[15] In Northeastern Korean tonal dialect, the two are comparable in height and the main contrast is in the second formant.[15] Within Seoul Korean, /o/ is raised toward /u/ while /ɯ/ is fronted away from /u/ in younger speakers’ speech.[15]

Middle Korean had an additional vowel phoneme denoted by ᆞ, known as arae-a (literally "lower a"). The vowel merged with [a] in all mainland varieties of Korean but remains distinct in Jeju, where it is pronounced [ɒ].

| IPA | Hangul | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /i/ | ㅣ | 시장 sijang | [ɕi.dʑɐŋ] | 'hunger' |

| /iː/ | 시장 sijang | [ɕiː.dʑɐŋ] | 'market' | |

| /e/ | ㅔ | 베개 begae | [pe̞.ɡɛ̝] | 'pillow' |

| /eː/ | 베다 beda | [peː.dɐ] | 'to cut' | |

| /ɛ/ | ㅐ | 태양 taeyang | [tʰɛ̝.jɐŋ] | 'sun' |

| /ɛː/ | 태도 taedo | [tʰɛː.do] | 'attitude' | |

| /a/ | ㅏ | 말 mal | [mɐl] | 'horse' |

| /aː/ | 말 mal | [mɐːl] | 'word, language' | |

| /o/ | ㅗ | 보리 bori | [po̞.ɾi] | 'barley' |

| /oː/ | 보수 bosu | [poː.su̞] | 'salary' | |

| /u/ | ㅜ | 구리 guri | [ku.ɾi] | 'copper' |

| /uː/ | 수박 subak | [suː.bäk̚] | 'watermelon' | |

| /ʌ/ | ㅓ | 벌 beol | [pʌl] | 'punishment' |

| /ʌː/ | 벌 beol | [pɘːl] | 'bee' | |

| /ɯ/ | ㅡ | 어른 eoreun | [ɘː.ɾɯn] | 'seniors' |

| /ɯː/ | 음식 eumsik | [ɯːm.ɕik̚] | 'food' | |

| /ø/ [we] | ㅚ | 교회 gyohoe | [ˈkʲoːɦø̞] ~ [kʲoː.βʷe̞] | 'church' |

| /øː/ [weː] | 외투 oetu | [ø̞ː.tʰu] ~ [we̞ː.tʰu] | 'overcoat' | |

| /y/ [ɥi] | ㅟ | 쥐 jwi | [t͡ɕy] ~ [t͡ɕʷi] | 'mouse' |

| /yː/ [ɥiː] | 귀신 gwisin | [ˈkyːɕin] ~ [ˈkʷiːɕin] | 'ghost' | |

Diphthongs and glides

Because they may follow consonants in initial position in a word, which no other consonant can do, and also because of Hangul orthography, which transcribes them as vowels, semivowels such as /j/ and /w/ are sometimes considered to be elements of rising diphthongs rather than separate consonant phonemes.

| IPA | Hangul | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /je/ | ㅖ | 예산 yesan | [je̞ː.sɐn] | 'budget' |

| /jɛ/ | ㅒ | 얘기 yaegi | [jɛ̝ː.ɡi] | 'story' |

| /ja/ [jɐ] | ㅑ | 야구 yagu | [jɐː.ɡu] | 'baseball' |

| /jo/ | ㅛ | 교사 gyosa | [kʲoː.sa] | 'teacher' |

| /ju/ | ㅠ | 유리 yuri | [ju.ɾi] | 'glass' |

| /jʌ/ | ㅕ | 여기 yeogi | [jʌ.ɡi] | 'here' |

| /wi ~ y/ [ɥi] | ㅟ | 뒤 dwi | [tʷi] | 'back' |

| /we/ | ㅞ | 궤 gwe | [kʷe̞] | 'chest' or 'box' |

| /wɛ/ | ㅙ | 왜 wae | [wɛ̝] | 'why' |

| /wa/ [wɐ] | ㅘ | 과일 gwail | [kʷɐː.il] | 'fruit' |

| /wʌ/ | ㅝ | 뭐 mwo | [mʷəː] | 'what' |

| /ɰi/ [ɰi ~ i] | ㅢ | 의사 uisa | [ɰi.sɐ] | 'doctor' |

In current pronunciation, /ɰi/ merges into /i/ after a consonant. Some analyses treat /ɯ/ as a central vowel and thus the marginal sequence /ɰi/ as having a central-vowel onset, which would be more accurately transcribed [ȷ̈i] or [ɨ̯i].[11]:12

Modern Korean has no falling diphthongs, with sequences like /a.i/ being considered as two separate vowels in hiatus. Middle Korean had a full set of diphthongs ending in /j/, which monophthongized into the front vowels in Early Modern Korean (/aj/ > /ɛ/, /əj/ [ej] > /e/, /oj/ > /ø/, /uj/ > /y/, /ɯj/ > /ɰi ~ i/).[11]:12 This is the reason why the hangul letters ㅐ, ㅔ, ㅚ and so on are represented as back vowels plus i.

Consonant assimilation

Through vowels

The vowel that most affects consonants is /i/, which, along with its semivowel homologue /j/, palatalizes /s/ and /s͈/ to alveolo-palatal [ɕ] and [ɕ͈] for most speakers (but see differences in the language between North Korea and South Korea). As noted above, initial |l| is silent in this palatalizing environment, at least in South Korea. Similarly, an underlying |t| or |tʰ| at the end of a morpheme becomes a phonemically palatalized affricate /tɕʰ/ when followed by a word or suffix beginning with /i/ or /j/ (it becomes indistinguishable from an underlying |tɕʰ|), but that does not happen within native Korean words such as /ʌti/ [ʌdi] "where?".

/kʰ/ is more affected by vowels, often becoming an affricate when followed by /i/ or /ɯ/: [cçi], [kxɯ]. The most variable consonant is /h/, which becomes a palatal [ç] before /i/ or /j/, a velar [x] before /ɯ/, and a bilabial [ɸʷ] before /o/, /u/ and /w/.[16]

| /i, j/ | /ɯ/ | /o, u, w/ | /a, ʌ, ɛ, e/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㅅ /s/ | [ɕ] | [s] | ||

| ㅆ /s͈/ | [ɕ͈] | [s͈] | ||

| ㄷ /t/ + suffix | [dʑ]- | [d]- | ||

| ㅌ /tʰ/ + suffix | [tɕʰ]- | [tʰ]- | ||

| ㅋ /kʰ/ | [cç] | [kx] | [kʰ] | |

| ㅎ /h/ word-initially | [ç] | [x] | [ɸʷ] | [h] |

| ㅎ /h/ intervocalically | [ʝ] | [ɣ] | [βʷ] | [ɦ] |

In many morphological processes, a vowel /i/ before another vowel may become the semivowel /j/. Likewise, /u/ and /o/, before another vowel, may reduce to /w/. In some dialects and speech registers, the semivowel /w/ assimilates into a following /e/ or /i/ and produces the front rounded vowels [ø] and [y].

Through other consonants

As noted above, tenuis stops and /h/ are voiced after the voiced consonants /m, n, ŋ, l/, and the resulting voiced [ɦ] tends to be elided. Tenuis stops become fortis after obstruents (which, as noted above, are reduced to [k̚, t̚, p̚]); that is, /kt/ is pronounced [k̚t͈]. Fortis and nasal stops are unaffected by either environment, though /n/ assimilates to /l/ after an /l/. After /h/, tenuis stops become aspirated, /s/ becomes fortis, and /n/ is unaffected.[lower-alpha 4] /l/ is highly affected: it becomes [n] after all consonants but /n/ (which assimilates to the /l/ instead) or another /l/. For example, underlying |tɕoŋlo| is pronounced /tɕoŋno/.[17]

These are all progressive assimilation. Korean also has regressive (anticipatory) assimilation: a consonant tends to assimilate in manner but not in place of articulation: Obstruents become nasal stops before nasal stops (which, as just noted, includes underlying |l|), but do not change their position in the mouth. Velar stops (that is, all consonants pronounced [k̚] in final position) become [ŋ]; coronals ([t̚]) become [n], and labials ([p̚]) become [m]. For example, |hankukmal| is pronounced /hankuŋmal/ (phonetically [hanɡuŋmal]).[17]

Before the fricatives /s, s͈/, coronal obstruents assimilate to a fricative, resulting in a geminate. That is, |tʰs| is pronounced /ss͈/ ([s͈ː]). A final /h/ assimilates in both place and manner, so that |hC| is pronounced as a geminate (and, as noted above, aspirated if C is a stop). The two coronal sonorants, /n/ and /l/, in whichever order, assimilate to /l/, so that both |nl| and |ln| are pronounced [lː].[17]

There are lexical exceptions to these generalizations. For example, voiced consonants occasionally cause a following consonant to become fortis rather than voiced; this is especially common with |ls| and |ltɕ| as [ls͈] and [lt͈ɕ], but is also occasionally seen with other sequences, such as |kjʌ.ulpaŋhak| ([kjʌulp͈aŋak̚]), |tɕʰamtoŋan| ([tɕʰamt͈oŋan]) and |wejaŋkanɯlo| ([wejaŋk͈anɯɾo]).[17]

2nd C 1st C |

coda |

ㄱ -g |

ㄲ -kk |

ㄷ -d |

ㄸ -tt |

ㄴ -n |

ㄹ -r |

ㅁ -m |

ㅂ -b |

ㅃ -pp |

ㅅ -s |

ㅆ -ss |

ㅈ -j |

ㅉ -jj |

ㅊ -ch |

ㅋ -k |

ㅌ -t |

ㅍ -p |

ㅎ -h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㅎ h- | n/a | k̚.kʰ | n/a | t̚.tʰ | n/a | n.n | n/a | p̚.pʰ | n/a | s.s͈ | n/a | t̚.tɕʰ | n/a | ||||||

| velar stops1 | k̚ | k̚.k͈ | k̚.t͈ | ŋ.n | ŋ.m | k̚.p͈ | k.s͈ | k̚.t͈ɕ | k̚.tɕʰ | k̚.kʰ | k̚.tʰ | k̚.pʰ | .kʰ | ||||||

| ㅇ ng- | ŋ | ŋ.ɡ | ŋ.k͈ | ŋ.d | ŋ.t͈ | ŋ.b | ŋ.p͈ | ŋ.sː | ŋ.s͈ | ŋ.dʑ | ŋ.t͈ɕ | ŋ.tɕʰ | ŋ.kʰ | ŋ.tʰ | ŋ.pʰ | ŋ.ɦ ~ .ŋ | |||

| coronal stops2 | t̚ | t̚.k͈ | t̚.t͈ | n.n | n.m | t̚.p͈ | s.s͈ | t̚.t͈ɕ | t̚.tɕʰ | t̚.kʰ | t̚.tʰ | t̚.pʰ | .tʰ | ||||||

| ㄴ n- | n | n.ɡ | n.k͈ | n.d | n.t͈ | n.n | l.l | n.b | n.p͈ | n.sː | n.s͈ | n.dʑ | n.t͈ɕ | n.tɕʰ | n.kʰ | n.tʰ | n.pʰ | n.ɦ ~ .n | |

| ㄹ r- | l | l.ɡ | l.k͈ | l.d | l.t͈ | l.l | l.m | l.b | l.p͈ | l.sː | l.s͈ | l.dʑ | l.t͈ɕ | l.tɕʰ | l.kʰ | l.tʰ | l.pʰ | l.ɦ ~ .ɾ | |

| labial stops3 | p̚ | p̚.k͈ | p̚.t͈ | m.n | m.m | p̚.p͈ | p.s͈ | p̚.t͈ɕ | p̚.tɕʰ | p̚.kʰ | p̚.tʰ | p̚.pʰ | .pʰ | ||||||

| ㅁ m- | m | m.ɡ | m.k͈ | m.d | m.t͈ | m.b | m.p͈ | m.sː | m.s͈ | m.dʑ | m.t͈ɕ | m.tɕʰ | m.kʰ | m.tʰ | m.pʰ | m.ɦ ~ .m | |||

- Velar obstruents found in final position: ㄱ g, ㄲ kk, ㅋ k

- Final coronal obstruents: ㄷ d, ㅌ t, ㅅ s, ㅆ ss, ㅈ j, ㅊ ch

- Final labial obstruents: ㅂ b, ㅍ p

The resulting geminate obstruents, such as [k̚k͈], [ss͈], [p̚pʰ], and [t̚tɕʰ] (that is, [k͈ː], [s͈ː], [pʰː], and [tːɕʰ]), tend to reduce ([k͈], [s͈], [pʰ], [tɕʰ]) in rapid conversation. Heterorganic obstruent sequences such as [k̚p͈] and [t̚kʰ] may, less frequently, assimilate to geminates ([p͈ː], [kːʰ]) and also reduce ([p͈], [kʰ]).

These sequences assimilate with following vowels the way single consonants do, so that for example |ts| and |hs| palatalize to [ɕɕ͈] (that is, [ɕ͈ː]) before /i/ and /j/; |hk| and |lkʰ| affricate to [kx] and [lkx] before /ɯ/; |ht|, |s͈h|, and |th| palatalize to [t̚tɕʰ] and [tɕʰ] across morpheme boundaries, and so on.

Hangul orthography does not generally reflect these assimilatory processes, but rather maintains the underlying morphology in most cases.

Phonotactics

Korean syllable structure is maximally CGVC, where G is a glide /j, w, ɰ/. Any consonant except /ŋ/ may occur initially, but only /p, t, k, m, n, ŋ, l/ may occur finally. Sequences of two consonants may occur between vowels, as outlined above. However, morphemes may also end in CC clusters, which are both expressed only when they are followed by a vowel. When the morpheme is not suffixed, one of the consonants is not expressed; if there is a /h/, which cannot appear in final position, it will be that. Otherwise it will be a coronal consonant (with the exception of /lb/, sometimes), and if the sequence is two coronals, the voiceless one (/s, tʰ, tɕ/) will drop, and /n/ or /l/ will remain. /lb/ either reduces to [l] (as in 짧다 [t͡ɕ͈alt͈a] "to be short"[18]) or to [p̚] (as in 밟다 [paːp̚t͈a] "to step"[19]); 여덟 [jʌdʌl] "eight" is always pronounced 여덜 even when followed by a vowel-initial particle.[20] Thus, no sequence reduces to [t̚] in final position.

Sequence ㄳ

gsㄺ

lgㄵ

njㄶ

nhㄽ

lsㄾ

ltㅀ

lhㄼ

lbㅄ

bsㄿ

lpㄻ

lmMedial allophone [k̚s͈] [lɡ] [ndʑ] [n(ɦ)] [ls͈] [ltʰ] [l(ɦ)] [lb] [p̚s͈] [lpʰ] [lm] Final allophone [k̚] [n] [l] [p̚] [m]

When such a sequence is followed by a consonant, the same reduction takes place, but a trace of the lost consonant may remain in its effect on the following consonant. The effects are the same as in a sequence between vowels: an elided obstruent will leave the third consonant fortis, if it is a stop, and an elided |h| will leave it aspirated. Most conceivable combinations do not actually occur;[lower-alpha 5] a few examples are |lh-tɕ| = [ltɕʰ], |nh-t| = [ntʰ], |nh-s| = [ns͈], |ltʰ-t| = [lt͈], |ps-k| = [p̚k͈], |ps-tɕ| = [p̚t͈ɕ]; also |ps-n| = [mn], as /s/ has no effect on a following /n/, and |ks-h| = [kʰ], with the /s/ dropping out.

When the second and third consonants are homorganic obstruents, they merge, becoming fortis or aspirate, and, depending on the word and a preceding |l|, might not elide: |lk-k| is [lk͈].

An elided |l| has no effect: |lk-t| = [k̚t͈], |lk-tɕ| = [k̚t͈ɕ], |lk-s| = [k̚s͈], |lk-n| = [ŋn], |lm-t| = [md], |lp-k| = [p̚k͈], |lp-t| = [p̚t͈], |lp-tɕ| = [p̚t͈ɕ], |lpʰ-t| = [p̚t͈], |lpʰ-tɕ| = [p̚t͈ɕ], |lp-n| = [mn].

Among vowels, the sequences /*jø, *jy, *jɯ, *ji; *wø, *wy, *wo, *wɯ, *wu/ do not occur, and it is not possible to write them using standard hangul.[lower-alpha 6] The semivowel [ɰ] occurs only in the diphthong /ɰi/, and is prone to being deleted after a consonant. There are no offglides in Korean; historical diphthongs /*aj, *ʌj, *uj, *oj, *ɯj/ have become modern monophthongs /ɛ/, /e/, /y ~ ɥi/, /ø ~ we/, /ɰi/.[11]:12

Vowel harmony

| Positive, "light", or "yang" vowels | ㅏ a | ㅑ ya | ㅗ o | ㅘ wa | ㅛ yo | (ㆍ ə) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㅐ ae | ㅒ yae | ㅚ oe | ㅙ wae | (ㆉ yoe) | (ㆎ əi) | |

| Negative, "heavy", or "yin" vowels | ㅓ eo | ㅕ yeo | ㅜ u | ㅝ wo | ㅠ yu | ㅡ eu |

| ㅔ e | ㅖ ye | ㅟ wi | ㅞ we | (ㆌ ywi) | ㅢ ui | |

| Neutral or center vowels | ㅣ i | |||||

| Obsolete and dialectal sounds in parentheses. | ||||||

Traditionally, the Korean language has had strong vowel harmony; that is, in pre-modern Korean, not only did the inflectional and derivational affixes (such as postpositions) change in accordance to the main root vowel, but native words also adhered to vowel harmony. It is not as prevalent in modern usage, although it remains strong in onomatopoeia, adjectives and adverbs, interjections, and conjugation. There are also other traces of vowel harmony in Korean.

There are three classes of vowels in Korean: positive, negative, and neutral. The vowel ㅡ (eu) is considered partially a neutral and negative vowel. The vowel classes loosely follow the negative and positive vowels; they also follow orthography. Exchanging positive vowels with negative vowels usually creates different nuances of meaning, with positive vowels sounding diminutive and negative vowels sounding crude:

- Onomatopoeia:

- 퐁당퐁당 (pongdang-pongdang) and 풍덩풍덩 (pungdeong-pungdeong), light and heavy water splashing

- Emphasised adjectives:

- 노랗다 (norata) means plain yellow, while its negative, 누렇다 (nureota), means very yellow

- 파랗다 (parata) means plain blue, while its negative, 퍼렇다 (peoreota), means deep blue

- Particles at the end of verbs:

- 잡다 (japda) (to catch) → 잡았다 (jabatda) (caught)

- 접다 (jeopda) (to fold) → 접었다 (jeobeotda) (folded)

- Interjections:

- 아이고 (aigo) and 어이구 (eoigu) expressing surprise, discomfort or sympathy

- 아하 (aha) and 어허 (eoheo) expressing sudden realization and mild objection, respectively

Dialectal pitch accents

Several dialects outside Seoul retain the Middle Korean pitch accent system. In the dialect of Northern Gyeongsang, in southeastern South Korea, any syllable may have pitch accent in the form of a high tone, as may the two initial syllables. For example, in trisyllabic words, there are four possible tone patterns:[21]

- 메누리 ménuri [mé.nu.ɾi] 'daughter-in-law'

- 어무이 eomú-i [ʌ.mú.i] 'mother'

- 원어민 woneomín [wʌ.nʌ.mín] 'native speaker'

- 오래비 órébi [ó.ɾé.bi] 'elder brother'

Notes

- Sometimes the tense consonants are marked with an apostrophe, ⟨ʼ⟩, but that is not IPA usage; in the IPA, the apostrophe indicates ejective consonants.

- The only fortis consonants to occur finally are ㄲ kk and ㅆ ss.

- Orthographically, it is found at the end of the name of the letter ㅎ, 히읗 hieut.

- Other consonants do not occur after /h/, which is uncommon in morpheme-final position.

- For example, morpheme-final |lp| occurs only in verb roots such as 밟 balb and is followed by only the consonants d, j, g, n.

- While 워 is romanized as wo, it does not represent [wo], but rather [wʌ].

References

- Sohn, Ho-Min (1994). Korean: Descriptive Grammar. Descriptive Grammars. London: Routledge. p. 432. ISBN 9780415003186.

- Cho, Taehong; Jun, Sun-Ah; Ladefoged, Peter (2002). "Acoustic and aerodynamic correlates of Korean stops and fricatives" (PDF). Journal of Phonetics. 30 (2): 193–228. doi:10.1006/jpho.2001.0153.

- Kim-Renaud, Young-Key, ed. (1997). The Korean Alphabet: Its History and Structure. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 9780824817237.

- Brown, Lucien; Yeon, Jaehoon, eds. (2015). The Handbook of Korean Linguistics. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781118370933.

- Kim, Young Shin (2011). An acoustic, aerodynamic and perceptual investigation of word-initial denasalization in Korean (Doctoral thesis). University College London.

- Kim, Mi-Ryoung; Beddor, Patrice Speeter; Horrocks, Julie (2002). "The contribution of consonantal and vocalic information to the perception of Korean initial stops". Journal of Phonetics. 30 (1): 77–100. doi:10.1006/jpho.2001.0152.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 293. ISBN 9780521661898.

- Kim, Mi-Ryoung; San, Duanmu (2004). "'Tense' and 'Lax' Stops in Korean". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 13 (1): 59–104. doi:10.1023/B:JEAL.0000007344.43938.4e. hdl:2027.42/42997.

- Chang, Charles B. (2013). "The production and perception of coronal fricatives in Seoul Korean: The case for a fourth laryngeal category" (PDF). Korean Linguistics. 15 (1): 7–49. doi:10.1075/kl.15.1.02cha.

- Lee, Hyun Bok (1999). "Korean". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–123. ISBN 9780521637510.

- Ahn, Sang-Cheol; Iverson, Gregory K. (2005). "Structured imbalances in the emergence of the Korean vowel system". In Salmons, Joseph C.; Dubenion-Smith, Shannon (eds.). Historical Linguistics 2005. Madison, WI: John Benjamins. pp. 275–293. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.557.3316. doi:10.1075/cilt.284.21ahn. ISBN 9789027247995.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (2000). The Korean Language. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0791448311.

- Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (2012). Tranter, Nicolas (ed.). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Oxon, UK: Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 9780415462877.

- Kwak, Chung-gu (2003). "The Vowel System of Contemporary Korean and Direction of Change". Journal of Korea Linguistics. 41: 59–91.

- Kang, Yoonjung; Schertz, Jessamyn L.; Han, Sungwoo (2015). "Vowels of Korean dialects". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 137 (4): 2414. doi:10.1121/1.4920798.

- Shin, Jiyoung; Kiaer, Jieun; Cha, Jaeeun (2012). The Sounds of Korean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9781107672680.

- 梅田, 博之 (1985). ハングル入門. Tokyo: NHK Publishing. ISBN 9784140350287.

- "짧다 - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "밟다 - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "여덟 - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- Jun, Jongho; Kim, Jungsun; Lee, Hayoung; Jun, Sun-Ah (2006). "The prosodic structure and pitch accent of Northern Kyungsang Korean" (PDF). Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 15 (4): 289–317. doi:10.1007/s10831-006-9000-2.

Further reading

- Cho, Young-mee (October 2016). "Korean Phonetics and Phonology". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.176. ISBN 9780199384655.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (1999). The Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36943-6.

- Yeon, Jaehoon; Brown, Lucien (2011). Korean: A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-60384-3.