Rhoticity in English

Rhoticity in English is the pronunciation of the historical rhotic consonant /r/ in all contexts by speakers of certain varieties of English. The presence or absence of rhoticity is one of the most prominent distinctions by which varieties of English can be classified. In rhotic varieties, the historical English /r/ sound is preserved in all pronunciation contexts. In non-rhotic varieties, speakers no longer pronounce /r/ in postvocalic environments—that is, when it is immediately after a vowel and not followed by another vowel.[1][2] For example, a rhotic English speaker pronounces the words hard and butter as /ˈhɑːrd/ and /ˈbʌtər/, whereas a non-rhotic speaker "drops" or "deletes" the /r/ sound, pronouncing them as /ˈhɑːd/ and /ˈbʌtə/.[lower-alpha 1] When an r is at the end of a word but the next word begins with a vowel, as in the phrase "tuner amp", most non-rhotic speakers will pronounce the /r/ in that position (the linking R), since it is followed by a vowel in this case. Not all non-rhotic varieties use the linking R; for example, it is absent in non-rhotic varieties of Southern American English.[5]

| History and description of |

| English pronunciation |

|---|

| Historical stages |

| General development |

| Development of vowels |

| Development of consonants |

| Variable features |

| Related topics |

The rhotic varieties of English include the dialects of Scotland, Ireland, and most of the United States and Canada. The non-rhotic varieties include most of the dialects of modern England, Wales, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In some varieties, such as those of some parts of the southern and northeastern United States,[6][2] rhoticity is a sociolinguistic variable: postvocalic r is deleted depending on an array of social factors such as the speaker's age, social class, ethnicity or the degree of formality of the speech event.

Evidence from written documents suggests that loss of postvocalic /r/ began sporadically during the mid-15th century, although these /r/-less spellings were uncommon and were restricted to private documents, especially ones written by women.[2] In the mid-18th century, postvocalic /r/ was still pronounced in most environments, but by the 1740s to 1770s it was often deleted entirely, especially after low vowels. By the early 19th century, the southern British standard was fully transformed into a non-rhotic variety, though some variation persisted as late as the 1870s.[7] This loss of postvocalic /r/ in British English influenced southern and eastern American port cities with close connections to Britain, causing their upper-class pronunciation to become non-rhotic while the rest of the United States remained rhotic.[8] Non-rhotic pronunciation continued to influence American prestige speech until the 1860s, when the American Civil War began to shift America's centers of wealth and political power to rhotic areas with fewer cultural connections to the old colonial and British elites.[9] The advent of radio and television in the 20th century established a national standard of American pronunciation that preserves historical /r/, with rhotic speech in particular becoming prestigious in the United States rapidly after the Second World War.[10]

History

England

The earliest traces of a loss of /r/ in English appear in the early 15th century and occur before coronal consonants, especially /s/, giving modern "ass (buttocks)" (Old English ears, Middle English ers or ars), and "bass (fish)" (OE bærs, ME bars).[2] A second phase of /r/-loss began during the 15th century, and was characterized by sporadic and lexically variable deletion, such as monyng "morning" and cadenall "cardinal".[2] These /r/-less spellings appear throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, but are uncommon and are restricted to private documents, especially ones written by women.[2] No English authorities describe loss of /r/ in the standard language prior to the mid-18th century, and many do not fully accept it until the 1790s.[2]

During the mid-17th century, a number of sources describe /r/ as being weakened but still present.[13] The English playwright Ben Jonson's English Grammar, published posthumously in 1640, records that /r/ was "sounded firme in the beginning of words, and more liquid in the middle, and ends."[7] The next major documentation of the pronunciation of /r/ appears a century later in 1740, when the British author of a primer for French students of English said: "...in many words r before a consonant is greatly softened, almost mute, and slightly lengthens the preceding vowel".[14]

By the 1770s, postvocalic /r/-less pronunciation was becoming common around London even in more formal, educated speech. The English actor and linguist John Walker used the spelling ar to indicate the long vowel of aunt in his 1775 rhyming dictionary.[4] In his influential Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language (1791), Walker reported, with a strong tone of disapproval, that "... the r in lard, bard, [...] is pronounced so much in the throat as to be little more than the middle or Italian a, lengthened into baa, baad...."[7] Americans returning to England after the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783 reported surprise at the significant changes in fashionable pronunciation.[15]

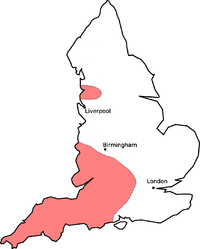

By the early 19th century, the southern British standard was fully transformed into a non-rhotic variety, though it continued to be variable as late as the 1870s.[7] The extent of rhoticity across England in the mid-19th century is summarized as widespread in the book New Zealand English: its Origins and Evolution:

- [T]he only areas of England ... for which we have no evidence of rhoticity in the mid-nineteenth century lie in two separate corridors. The first runs south from the North Riding of Yorkshire through the Vale of York into north and central Lincolnshire, nearly all of Nottinghamshire, and adjacent areas of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, and Staffordshire. The second includes all of Norfolk, western Suffolk and Essex, eastern Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire, Middlesex, and northern Surrey and Kent.[16]

Recordings of prisoners of war from the First World War in the Berliner Lautarchiv show rhoticity from dialects where the feature has since died out (e.g. Wakefield in Yorkshire).[17]

North America

The loss of postvocalic /r/ in the British prestige standard in the late 18th and early 19th centuries influenced American port cities with close connections to Britain, and caused upper-class pronunciation in many eastern and southern port cities such as New York City, Boston, Alexandria, Charleston, and Savannah to become non-rhotic.[8] Like regional dialects in England, the accents of other areas in America remained rhotic in a display of linguistic "lag" that preserved the original pronunciation of /r/.[8]

Non-rhotic pronunciation continued to influence American prestige speech until the 1860s, when the American Civil War shifted America's centers of wealth and political power to areas with fewer cultural connections to the British elite.[9] This trend increased after the Second World War.[10] This largely removed the prestige associated with non-rhotic pronunciation in America, so that when the advent of radio and television in the 20th century established a national standard of American pronunciation, it became a rhotic variety that preserves historical /r/.[9]

Modern pronunciation

In most non-rhotic accents, if a word ending in written "r" is followed immediately by a word beginning with a vowel, the /r/ is pronounced—as in water ice. This phenomenon is referred to as "linking R". Many non-rhotic speakers also insert an epenthetic /r/ between vowels when the first vowel is one that can occur before syllable-final r (drawring for drawing). This so-called "intrusive R" has been stigmatized, but nowadays many speakers of Received Pronunciation (RP) frequently "intrude" an epenthetic /r/ at word boundaries, especially where one or both vowels is schwa; for example the idea of it becomes the idea-r-of it, Australia and New Zealand becomes Australia-r-and New Zealand, the formerly well-known India-r-Office and "Laura Norder" (Law and Order). The typical alternative used by RP speakers (and some rhotic speakers as well) is to insert a glottal stop where an intrusive R would otherwise be placed.[18][19]

For non-rhotic speakers, what was historically a vowel plus /r/ is now usually realized as a long vowel. This is called compensatory lengthening, lengthening that occurs after the elision of a sound. So in RP and many other non-rhotic accents card, fern, born are pronounced [kɑːd], [fɜːn], [bɔːn] or similar (actual pronunciations vary from accent to accent). This length may be retained in phrases, so while car pronounced in isolation is [kɑː], car owner is [ˈkɑːrəʊnə]. But a final schwa usually remains short, so water in isolation is [wɔːtə]. In RP and similar accents the vowels /iː/ and /uː/ (or /ʊ/), when followed by r, become diphthongs ending in schwa, so near is [nɪə] and poor is [pʊə], though these have other realizations as well, including monophthongal ones; once again, the pronunciations vary from accent to accent. The same happens to diphthongs followed by R, though these may be considered to end in /ər/ in rhotic speech, and it is the /ər/ that reduces to schwa as usual in non-rhotic speech: tire said in isolation is [taɪə] and sour is [saʊə].[20] For some speakers, some long vowels alternate with a diphthong ending in schwa, so wear may be [wɛə] but wearing [ˈwɛːɹɪŋ].

The compensatory lengthening view is challenged by Wells, who states that during the seventeenth century stressed vowels followed by /r/ and another consonant or word boundary underwent a lengthening process known as Pre-R Lengthening. This process was not a compensatory lengthening process but an independent development, which explains why modern pronunciations feature both [ɜː] (bird, fur) and [ɜːr] (stirring, stir it) according to their positions: [ɜːr] was the regular outcome of the lengthening, which shortened to [ɜː] after R-Dropping in the eighteenth century; the lengthening involved 'mid and open short vowels', meaning that the lengthening of /ɑː/ in car was not a compensatory process due to R-Dropping.[21]

Even General American speakers commonly drop the /r/ in non-final unstressed syllables when another syllable in the same word also contains /r/; this may be referred to as R-dissimilation. Examples include the dropping of the first /r/ in the words surprise, governor and caterpillar. In more careful speech, however, the /r/ sounds are all retained.[22]

Distribution

Rhotic accents include most varieties of Scottish English, Irish or Hiberno-English, North American English, Barbadian English, Indian English,[24] and Pakistani English.[25]

Non-rhotic accents include most varieties of English English, Welsh English, New Zealand English, Australian English, South African English and Trinidadian and Tobagonian English.

Semi-rhotic accents have also been studied, such as Jamaican English, in which r is pronounced (as in even non-rhotic accents) before vowels, but also in stressed monosyllables or stressed syllables at the ends of words (e.g. in "car" or "dare"); however, it is not pronounced at the end of unstressed syllables (e.g. in "water") or before consonants (e.g. "market").[26]

Variably rhotic accents are also widely documented, in which deletion of r (when not before vowels) is optional; in these dialects the probability of deleting r may vary depending on social, stylistic, and contextual factors. Variably rhotic accents comprise much of Caribbean English, for example, as spoken in Tobago, Guyana, Antigua and Barbuda, and the Bahamas.[27] They also include current-day New York City English,[28] New York Latino English, and some Boston English, as well as some varieties of Scottish English.[29]

Non-rhotic accents in the Americas include those of the rest of the Caribbean and Belize.

England

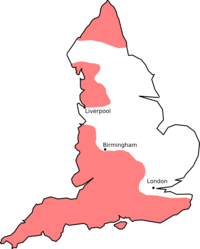

Though most English varieties in England are non-rhotic today, stemming from a trend toward this in southeastern England accelerating in the very late 18th century onwards, rhotic accents are still found in the West Country (south and west of a line from near Shrewsbury to around Portsmouth), the Corby area, some of Lancashire (north and west of the centre of Manchester), some parts of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, and in the areas that border Scotland. The prestige form, however, exerts a steady pressure toward non-rhoticity. Thus the urban speech of Bristol or Southampton is more accurately described as variably rhotic, the degree of rhoticity being reduced as one moves up the class and formality scales.[30]

Scotland

Most Scottish accents are rhotic, but non-rhotic speech has been reported in Edinburgh since the 1970s and Glasgow since the 1980s.[29]

United States

American English is predominantly rhotic today, but at the end of the 1800s non-rhotic accents were common throughout much of the coastal Eastern and Southern U.S., including along the Gulf Coast. In fact, non-rhotic accents were established in all major U.S. cities along the Atlantic coast except for the Delaware Valley area, with its early Scots-Irish influence, centered around Philadelphia and Baltimore. Since the American Civil War and even more intensely during the early to mid-1900s (presumably correlated with the Second World War),[10] rhotic accents began to gain social prestige nationwide, even in the aforementioned traditionally non-rhotic areas. Thus, non-rhotic accents are increasingly perceived by Americans as sounding foreign or less educated due to an association with working-class or immigrant speakers in Eastern and Southern cities, while rhotic accents are increasingly perceived as sounding more "General American".[31]

Today, non-rhoticity in the American South is found primarily among older speakers, and only in some areas such as central and southern Alabama; Savannah, Georgia; and Norfolk, Virginia,[6] as well as in the Yat accent of New Orleans. The local dialects of eastern New England, especially Boston, Massachusetts, extending into the states of Maine and (less so) New Hampshire, show some non-rhoticity, as well as the traditional Rhode Island dialect; however, this feature has been receding in the recent generations. The New York City dialect is traditionally non-rhotic, though William Labov more precisely classifies its current form as variably rhotic,[32] with many of its sub-varieties now fully rhotic, such as in northeastern New Jersey.

African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) is largely non-rhotic, and in some non-rhotic Southern and AAVE accents, there is no linking r, that is, /r/ at the end of a word is deleted even when the following word starts with a vowel, so that "Mister Adams" is pronounced [mɪstə(ʔ)ˈædəmz].[33] In a few such accents, intervocalic /r/ is deleted before an unstressed syllable even within a word when the following syllable begins with a vowel. In such accents, pronunciations like [kæəˈlaːnə] for Carolina, or [bɛːˈʌp] for "bear up" are heard.[34] This pronunciation also occurs in AAVE[35] and also occurred for many older non-rhotic Southern speakers.[36]

Typically, even non-rhotic modern varieties of American English pronounce the /r/ in /ɜr/ (as in "bird," "work," or "perky") and realize it, as in most rhotic varieties, as [ɚ] (![]()

Canada

Canadian English is entirely rhotic except for small isolated areas in southwestern New Brunswick, parts of Newfoundland, and the Lunenburg English variety spoken in Lunenburg and Shelburne Counties, Nova Scotia, which may be non-rhotic or variably rhotic.[37]

Ireland

The prestige form of English spoken in Ireland is rhotic and most regional accents are rhotic although some regional accents, particularly in the area around counties Louth and Cavan are notably non-rhotic and many non-prestige accents have touches of non-rhoticity. In Dublin, the traditional local dialect is largely non-rhotic but the more modern varieties, referred to by Hickey as "mainstream Dublin English" and "fashionable Dublin English", are fully rhotic. Hickey used this as an example of how English in Ireland does not follow prestige trends in England.[38]

Asia

The English spoken in Asia is predominantly rhotic. Many varieties of Indian English are rhotic owing to the underlying phonotactics of the native Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages[24] whilst some tend to be non-rhotic. In the case of the Philippines, this may be explained because the English that is spoken there is heavily influenced by the American dialect. In addition, many East Asians (in Mainland China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan) who have a good command of English generally have rhotic accents because of the influence of American English. This excludes Hong Kong, whose RP English dialect is a result of its almost 150-year-history as a British Crown colony (later British dependent territory). The lack of consonant /r/ in Cantonese also contributes to the phenomenon (although rhoticity started to exist due to the handover in 1997 and influence by US and East Asian entertainment industry). However, many older (and younger) speakers among South and East Asians have a non-rhotic accent.

Other Asian regions with non-rhotic English are Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei.[39] A typical Malaysian's English would be almost totally non-rhotic due to the nonexistence of rhotic endings in both languages of influence, whereas a more educated Malaysian's English may be non-rhotic due to Standard Malaysian English being based on RP (Received Pronunciation). The classical English spoken in Brunei is non-rhotic. But one current change that seems to be taking place is that Brunei English is becoming rhotic, partly influenced by American English and partly influenced by the rhoticity of Standard Malay, also influenced by languages of Indians in Brunei (Tamil and Punjabi) (rhoticity is also used by Chinese Bruneians), although English in neighboring Malaysia, Singapore, and Australia remains non-rhotic; rhoticity in Brunei English is equal to Philippine and Indian dialects of English and Scottish and Irish dialects. Non-rhoticity is mostly found in older generations, its phenomenon is almost similar to the status of American English, wherein non-rhoticity reduced greatly.[40][41]

A typical teenager's Southeast Asian English would be rhotic,[42] mainly because of prominent influence by American English.[42] Spoken English in Myanmar is non-rhotic, but there are a number of English speakers with a rhotic or partially rhotic pronunciation. Sri Lankan English may be rhotic.

Africa

The English spoken in most of Africa is based on RP and is generally non-rhotic. Pronunciation and variation in African English accents are largely affected by native African language influences, level of education and exposure to Western influences. The English accents spoken in the coastal areas of West Africa are primarily non-rhotic as are the underlying varieties of Niger-Congo languages spoken in that part of West Africa. Rhoticity may be present in English spoken in areas where rhotic Afro-Asiatic or Nilo Saharan languages are spoken across northern West Africa and in the Nilotic regions of East Africa. More modern trends show an increasing American influence on African English pronunciation particularly among younger urban affluent populations, where the American rhotic 'r' may be over-stressed in informal communication to create a pseudo-Americanised accent. By and large official spoken English used in post colonial African countries is non-rhotic. Standard Liberian English is also non-rhotic because liquids are lost at the end of words or before consonants.[43] South African English is mostly non-rhotic, especially Cultivated dialect based on RP, except for some Broad varieties spoken in the Cape Province (typically in -er suffixes, as in writer). It appears that postvocalic /r/ is entering the speech of younger people under the influence of American English, and maybe an influence of Scottish dialect brought by Scottish settlers.[44][45]

Australia

Standard Australian English is non-rhotic. A degree of rhoticity has been observed in a particular sublect of Australian Aboriginal English spoken on the coast of South Australia, especially in speakers from the Point Pearce and Raukkan settlements. These speakers realise /r/ as [ɹ] in the preconsonantal postvocalic position – after a vowel but before another a consonant – but only within stems. For example: [boːɹd] "board", [tʃɜɹtʃ] "church", [pɜɹθ] "Perth"; but [flæː] "flour", [dɒktə] "doctor", [jɪəz] "years". It has been speculated that this feature may derive from the fact that many of the first settlers in coastal South Australia – including Cornish tin-miners, Scottish missionaries, and American whalers – spoke rhotic varieties.[46]

New Zealand

Although New Zealand English is predominantly non-rhotic, Southland and parts of Otago in the far south of New Zealand's South Island are rhotic from apparent Scottish influence.[47] Older Southland speakers use /ɹ/ variably after vowels, but today younger speakers use /ɹ/ only with the NURSE vowel and occasionally with the LETTER vowel. Younger Southland speakers pronounce /ɹ/ in third term /ˌθɵːɹd ˈtɵːɹm/ (General NZE pronunciation: /ˌθɵːd ˈtɵːm/) but sometimes in farm cart /fɐːm kɐːt/ (same as in General NZE).[48] However, non-prevocalic /ɹ/ among non-rhotic speakers is sometimes pronounced in a few words, including Ireland /ˈɑɪɹlənd/, merely /ˈmiəɹli/, err /ɵːɹ/, and the name of the letter R /ɐːɹ/ (General NZE pronunciations: /ˈɑɪlənd, ˈmiəli, ɵː, ɐː/).[49] The Māori accent varies from the European-origin New Zealand accent; some Māori speakers are semi-rhotic like most white New Zealand speakers, although it is not clearly identified to any particular region or attributed to any defined language shift. The Māori language itself tends in most cases to use an r with an alveolar tap [ɾ], like Scottish dialect.[50]

Mergers characteristic of non-rhotic accents

Some phonemic mergers are characteristic of non-rhotic accents. These usually include one item that historically contained an R (lost in the non-rhotic accent), and one that never did so. The section below lists mergers in order of approximately decreasing prevalence.

Batted–battered merger

This merger is present in non-rhotic accents which have undergone the weak vowel merger. Such accents include Australian, New Zealand, most South African speech, and some non-rhotic English speech (e.g. Norfolk, Sheffield). The third edition of Longman Pronunciation Dictionary lists /əd/ (and /əz/ mentioned below) as possible (though less common than /ɪd/ and /ɪz/) British pronunciations, which means that the merger is an option even in RP.

A large number of homophonous pairs involve the syllabic -es and agentive -ers suffixes, such as merges-mergers and bleaches-bleachers. Because there are so many, they are excluded from the list of homophonous pairs below.

| /ɪ̈/ | /ər/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| batted | battered | ˈbætəd | |

| betted | bettered | ˈbɛtəd | |

| busted | bustard | ˈbʌstəd | |

| butches | butchers | ˈbʊtʃəz | |

| butted | buttered | ˈbʌtəd | |

| charted | chartered | ˈtʃɑːtəd | |

| chatted | chattered | ˈtʃætəd | |

| founded | foundered | ˈfaʊndəd | |

| humid | humo(u)red | ˈhjuːməd | |

| masted | mastered | ˈmæstəd, ˈmɑːstəd | |

| matted | mattered | ˈmætəd | |

| modding | modern | ˈmɒdən | With G-dropping. |

| patted | pattered | ˈpætəd | |

| patting | pattern | ˈpætən | With G-dropping. |

| satin | Saturn | ˈsætən | |

| scatted | scattered | ˈskætəd | |

| splendid | splendo(u)red | ˈsplɛndəd | |

| tatted | tattered | ˈtætəd | |

| tended | tendered | ˈtɛndəd | |

| territory | terror tree | ˈtɛrətriː | With happy-tensing. |

Bud–bird merger

A merger of /ɜː(r)/ and /ʌ/ occurring for some speakers of Jamaican English making bud and bird homophones as /bʌd/.[51] The conversion of /ɜː/ to [ʌ] or [ə] is also found in places scattered around England and Scotland. Some speakers, mostly rural, in the area from London to Norfolk exhibit this conversion, mainly before voiceless fricatives. This gives pronunciation like first [fʌst] and worse [wʌs]. The word cuss appears to derive from the application of this sound change to the word curse. Similarly, lurve is coined from love.

| /ʌ/ | /ɜːr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| blood | blurred | ˈblʌd | |

| bub | burb | ˈbʌb | |

| buck | Burke | ˈbʌk | |

| Buckley | Berkeley | ˈbʌkli | |

| bud | bird | ˈbʌd | |

| bud | burred | ˈbʌd | |

| budging | burgeon | ˈbʌdʒən | With weak vowel merger and G-dropping. |

| bug | berg | ˈbʌɡ | |

| bug | burg | ˈbʌɡ | |

| bugger | burger | ˈbʌɡə | |

| bugging | bergen; Bergen | ˈbʌɡən | With weak vowel merger and G-dropping. |

| bummer | Burma | ˈbʌmə | |

| bun | Bern | ˈbʌn | |

| bun | burn | ˈbʌn | |

| bunt | burnt | ˈbʌnt | |

| bused; bussed | burst | ˈbʌst | |

| bust | burst | ˈbʌst | |

| but | Bert | ˈbʌt | |

| but | Burt | ˈbʌt | |

| butt | Bert | ˈbʌt | |

| butt | Burt | ˈbʌt | |

| button | Burton | ˈbʌtən | |

| buzz | burrs | ˈbʌz | |

| chuck | chirk | ˈtʃʌk | |

| cluck | clerk | ˈklʌk | |

| colo(u)r | curler | ˈkʌlə | |

| coven | curving | ˈkʌvən | With weak vowel merger and G-dropping. |

| cub | curb | ˈkʌb | |

| cub | kerb | ˈkʌb | |

| cud | curd | ˈkʌd | |

| cud | curred | ˈkʌd | |

| cud | Kurd | ˈkʌd | |

| cuddle | curdle | ˈkʌdəl | |

| cuff you | curfew | ˈkʌfju | |

| cull | curl | ˈkʌl | |

| culler | curler | ˈkʌlə | |

| cunning | kerning | ˈkʌnɪŋ | |

| cuss | curse | ˈkʌs | |

| cut | curt; Curt | ˈkʌt | |

| cutting | curtain | ˈkʌtɪn | With G-dropping. |

| dost | durst | ˈdʌst | |

| doth | dearth | ˈdʌθ | |

| duck | dirk | ˈdʌk | |

| ducked | dirked | ˈdʌkt | |

| ducks | dirks | ˈdʌks | |

| duct | dirked | ˈdʌkt | |

| dust | durst | ˈdʌst | |

| dux | dirks | ˈdʌks | |

| fud | furred | ˈfʌd | |

| fun | fern | ˈfʌn | |

| fussed | first | ˈfʌst | |

| fuzz | furs | ˈfʌz | |

| gull | girl | ˈɡʌl | |

| gully | girly | ˈɡʌli | |

| gutter | girder | ˈɡʌɾə | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| hub | herb | ˈ(h)ʌb | With or without H-dropping. |

| huck | Herc | ˈhʌk | |

| huck | irk | ˈʌk | With H-dropping. |

| huddle | hurdle | ˈhʌdəl | |

| hull | hurl | ˈhʌl | |

| hum | herm | ˈhʌm | |

| Hun | earn | ˈʌn | With H-dropping. |

| Hun | urn | ˈʌn | With H-dropping. |

| hush | Hirsch | ˈhʌʃ | |

| hut | hurt | ˈhʌt | |

| love | lurve | ˈlʌv | |

| luck | lurk | ˈlʌk | |

| lucks | lurks | ˈlʌks | |

| lunt | learnt | ˈlʌnt | |

| luxe | lurks | ˈlʌks | |

| much | merch | ˈmʌtʃ | |

| muck | merc | ˈmʌk | |

| muck | mirk | ˈmʌk | |

| muck | murk | ˈmʌk | |

| muddle | myrtle | ˈmʌɾəl | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| mudder | murder | ˈmʌdə | |

| mull | merl | ˈmʌl | |

| mutter | murder | ˈmʌɾə | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| mutton | Merton | ˈmʌtən | |

| oven | Irving | ˈʌvən | With weak vowel merger and G-dropping. |

| puck | perk | ˈpʌk | |

| pudge | purge | ˈpʌdʒ | |

| pup | perp | ˈpʌp | |

| pus | purse | ˈpʌs | |

| pussy (pus) | Percy | ˈpʌsi | |

| putt | pert | ˈpʌt | |

| scut | skirt | ˈskʌt | |

| shuck | shirk | ˈʃʌk | |

| spun | spurn | ˈspʌn | |

| stud | stirred | ˈstʌd | |

| such | search | ˈsʌtʃ | |

| suck | cirque | ˈsʌk | |

| suckle | circle | ˈsʌkəl | |

| suffer | surfer | ˈsʌfə | |

| sully | surly | ˈsʌli | |

| Sutton | certain | ˈsʌtən | With weak vowel merger. |

| thud | third | ˈθʌd | |

| ton(ne) | tern | ˈtʌn | |

| ton(ne) | turn | ˈtʌn | |

| tough | turf | ˈtʌf | |

| tuck | Turk | ˈtʌk | |

| tucks | Turks | ˈtʌks | |

| Tuttle | turtle | ˈtʌtəl | |

| tux | Turks | ˈtʌks | |

| us | Erse | ˈʌs | |

| wont | weren't | ˈwʌnt |

Comma–letter merger

In the terminology of John C. Wells, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets comma and letter. It is found in all or nearly all non-rhotic accents,[52] and is even present in some accents that are in other respects rhotic, such as those of some speakers in Jamaica and the Bahamas.[52]

In some accents, syllabification may interact with rhoticity, resulting in homophones where non-rhotic accents have centering diphthongs. Possibilities include Korea–career,[53] Shi'a–sheer, and Maia–mire,[54] while skua may be identical with the second syllable of obscure.[55]

| /ə/ | /ər/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ana | honor | ˈɑːnə | With father-bother merger. |

| Anna | honor | ˈɑːnə | In American English, with father-bother merger. In the UK, Anna can be pronounced /ˈænə/. |

| area | airier | ˈɛəriə | |

| Basia | basher | ˈbæʃə | In British English. In North America, Basia can be pronounced /ˈbɑːʃə/. |

| CAPTCHA | capture | ˈkæptʃə | |

| Carla | collar | ˈkɑːlə | With god-guard merger. |

| Carta | Carter | ˈkɑːtə | |

| cheetah | cheater | ˈtʃiːtə | |

| Darla | dollar | ˈdɑlə | With god-guard merger. |

| Dinah | diner | ˈdaɪnə | |

| coca | coker | ˈkoʊkə | |

| coda | coder | ˈkoʊdə | |

| cola | coaler | ˈkoʊlə | |

| coma | comber | ˈkoʊmə | |

| custody | custardy | ˈkʌstədi | |

| data | dater | ˈdeɪtə | |

| Dhaka | darker | ˈdɑːkə | In American English. In the UK, Dhaka is /ˈdækə/. |

| Easton | eastern | ˈiːstən | |

| FEMA | femur | ˈfiːmə | |

| Ghana | Garner | ˈɡɑːnə | |

| Helena | Eleanor | ˈɛlənə | With h-dropping. Outside North America. |

| eta | eater | ˈiːtə | |

| eyen | iron | ˈaɪən | |

| feta | fetter | ˈfɛtə | |

| formally | formerly | ˈfɔːməli | |

| geta | getter | ˈɡɛtə | |

| ion | iron | ˈaɪən | |

| karma | calmer | ˈkɑːmə | |

| kava | carver | ˈkɑːvə | |

| Lena | leaner | ˈliːnə | |

| Lima | lemur | ˈliːmə | |

| Lisa | leaser | ˈliːsə | |

| Luna | lunar | ˈl(j)uːnə | |

| Maia | Meier | ˈmaɪə | |

| Maia | mire | ˈmaɪə | |

| Maya | Meier | ˈmaɪə | |

| Maya | mire | ˈmaɪə | |

| manna | manner | ˈmænə | |

| manna | manor | ˈmænə | |

| Marta | martyr | ˈmɑːtə | |

| Mia | mere | ˈmɪə | |

| miner | myna(h); mina(h) | ˈmaɪnə | |

| minor | myna(h); mina(h) | ˈmaɪnə | |

| Mona | moaner | ˈmoʊnə | |

| Nia | near | ˈnɪə | |

| Palma | palmer; Palmer | ˈpɑːmə | |

| panda | pander | ˈpændə | |

| parka | Parker | ˈpɑːkə | |

| Parma | palmer; Palmer | ˈpɑːmə | |

| Patton | pattern | ˈpætən | |

| PETA | peter; Peter | ˈpiːtə | |

| pharma | farmer | ˈfɑːmə | |

| Pia | peer | ˈpɪə | |

| Pia | pier | ˈpɪə | |

| pita | peter; Peter | ˈpiːtə | "pita" may also be pronounced ˈpɪtə and therefore not merged |

| Rhoda | rotor | ˈroʊɾə | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| Rita | reader | ˈriːɾə | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| Roma | roamer | ˈroʊmə | |

| rota | rotor | ˈroʊtə | |

| Saba | sabre; saber | ˈseɪbə | |

| schema | schemer | ˈskiːmə | |

| Sia | sear | ˈsɪə | |

| Sia | seer | ˈsɪə | |

| seven | Severn | ˈsɛvən | |

| soda | solder | ˈsoʊdə | "solder" may also be pronounced ˈsɒdə(r) and therefore not merged |

| soya | sawyer | ˈsɔɪə | |

| Stata | starter | ˈstɑːtə | Stata is also pronounced /ˈstætə/ and /ˈsteɪtə/. |

| taiga | tiger | ˈtaɪɡə | |

| terra; Terra | terror | ˈtɛrə | |

| Tia | tear (weep) | ˈtɪə | |

| tuba | tuber | ˈt(j)uːbə | |

| tuna | tuner | ˈt(j)uːnə | |

| Vespa | vesper | ˈvɛspə | |

| via | veer | ˈvɪə | |

| Wanda | wander | ˈwɒndə | |

| Weston | western | ˈwɛstən | |

| Wicca | wicker | ˈwɪkə |

Dough–door merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets GOAT and FORCE. It may be found in some southern U.S. non-rhotic speech, some speakers of African-American English, some speakers in Guyana and some Welsh speech.[52]

| /oʊ/ | /oʊr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| beau | boar | ˈboʊ | |

| beau | bore | ˈboʊ | |

| bode | board | ˈboʊd | |

| bode | bored | ˈboʊd | |

| bone | borne | ˈboʊn | |

| bone | Bourne | ˈboʊn | |

| bow | boar | ˈboʊ | |

| bow | bore | ˈboʊ | |

| bowed | board | ˈboʊd | |

| bowed | bored | ˈboʊd | |

| chose | chores | ˈtʃoʊz | |

| coast | coursed | ˈkoʊst | |

| coat | court | ˈkoʊt | |

| code | cored | ˈkoʊd | |

| doe | door | ˈdoʊ | |

| does | doors | ˈdoʊz | |

| dough | door | ˈdoʊ | |

| doze | doors | ˈdoʊz | |

| floe | floor | ˈfloʊ | |

| flow | floor | ˈfloʊ | |

| foe | fore | ˈfoʊ | |

| foe | four | ˈfoʊ | |

| go | gore | ˈɡoʊ | |

| goad | gored | ˈɡoʊd | |

| hoe | whore | ˈhoʊ | |

| hoed | hoard | ˈhoʊd | |

| hoed | horde | ˈhoʊd | |

| hoed | whored | ˈhoʊd | |

| hoes | whores | ˈhoʊz | |

| hose | whores | ˈhoʊz | |

| lo | lore | ˈloʊ | |

| load | lord; Lord | ˈloʊd | |

| lode | lord; Lord | ˈloʊd | |

| low | lore | ˈloʊ | |

| moan | mourn | ˈmoʊn | |

| Moe | Moore | ˈmoʊ | |

| Moe | more | ˈmoʊ | |

| Mona | mourner | ˈmoʊnə | |

| mow | Moore | ˈmoʊ | |

| mow | more | ˈmoʊ | |

| mown | mourn | ˈmoʊn | |

| O | oar | ˈoʊ | |

| O | ore | ˈoʊ | |

| ode | oared | ˈoʊd | |

| oh | oar | ˈoʊ | |

| oh | ore | ˈoʊ | |

| owe | oar | ˈoʊ | |

| owe | ore | ˈoʊ | |

| owed | oared | ˈoʊd | |

| Po | pore | ˈpoʊ | |

| Po | pour | ˈpoʊ | |

| Poe | pore | ˈpoʊ | |

| Poe | pour | ˈpoʊ | |

| poach | porch | ˈpoʊtʃ | |

| poke | pork | ˈpoʊk | |

| pose | pores | ˈpoʊz | |

| pose | pours | ˈpoʊz | |

| road | roared | ˈroʊd | |

| rode | roared | ˈroʊd | |

| roe | roar | ˈroʊ | |

| rose | roars | ˈroʊz | |

| row | roar | ˈroʊ | |

| rowed | roared | ˈroʊd | |

| sew | soar | ˈsoʊ | |

| sew | sore | ˈsoʊ | |

| sewed | soared | ˈsoʊd | |

| sewed | sored | ˈsoʊd | |

| sewed | sword | ˈsoʊd | |

| shone | shorn | ˈʃoʊn | |

| show | shore | ˈʃoʊ | |

| shown | shorn | ˈʃoʊn | |

| snow | snore | ˈsnoʊ | |

| so | soar | ˈsoʊ | |

| so | sore | ˈsoʊ | |

| sow | soar | ˈsoʊ | |

| sow | sore | ˈsoʊ | |

| sowed | soared | ˈsoʊd | |

| sowed | sored | ˈsoʊd | |

| sowed | sword | ˈsoʊd | |

| stow | store | ˈstoʊ | |

| Thoth | tort | ˈtoʊt | With th-stopping. |

| toad | toward | ˈtoʊd | |

| toe | tore | ˈtoʊ | |

| toed | toward | ˈtoʊd | |

| tone | torn | ˈtoʊn | |

| tote | tort | ˈtoʊt | |

| tow | tore | ˈtoʊ | |

| towed | toward | ˈtoʊd | |

| woe | wore | ˈwoʊ | |

| whoa | wore | ˈwoʊ | With wine–whine merger. |

| yo | yore | ˈjoʊ | |

| yo | your | ˈjoʊ |

Face–square–near merger

The merger of the lexical sets FACE, SQUARE and NEAR is possible in Jamaican English and partially also in Northern East Anglian English. From a historical viewpoint, it is a complete absorption of /r/ into the preceding vowel (cf. father-farther merger and pawn-porn merger).

In Jamaica, the merger occurs after deletion of the postvocalic /r/ in a preconsonantal position, so that fade can be homophonous with feared as [feːd], but day [deː] is normally distinct from dear [deːɹ], though vowels in both words can be analyzed as belonging to the same phoneme (followed by /r/ in the latter case, so that the merger of FACE and SQUARE/NEAR does not occur). In Jamaican Patois, the merged vowel is an opening diphthong [iɛ] and that realization can also be heard in Jamaican English, mostly before a sounded /r/ (so that fare and fear can be both [feːɹ] and [fiɛɹ]), but sometimes also in other positions. Alternatively, /eː/ can be laxed to [ɛ] before a sounded /r/, which produces a variable Mary-merry merger: [fɛɹ].[56]

It is possible in northern East Anglian varieties (to [e̞ː]), but only in the case of items descended from ME /aː/, such as daze. Those descended from ME /ai/ (such as days) have a distinctive /æi/ vowel. It appears to be receding, as items descended from ME /aː/ are being transferred to the /æi/ class; in other words, a pane-pain merger is taking place. In the southern dialect area, the pane-pain merger is complete and all three vowels are distinct: FACE is [æi], SQUARE is [ɛː] and NEAR is [ɪə].[57]

A near-merger of FACE and SQUARE is possible in General South African English, but the vowels typically remain distinct as [eɪ] (for FACE) and [eː] (for SQUARE). The difference between the two phonemes is so subtle that they're [ðeː] can be misheard as they [ðeɪ] (see zero copula). In other varieties the difference can be greater, e.g. [ðeː] vs. [ðʌɪ] in Broad SAE and [ðɛə] vs. [ðeɪ] in the Cultivated variety. Even in General SAE, SQUARE can be [ɛə] or [ɛː], strongly distinguished from FACE [eɪ]. NEAR remains distinct in all varieties, typically as [ɪə].[58][59]

In the Cardiff dialect SQUARE can also be similar to cardinal [e] (though long [eː], as in South Africa), but FACE typically has a fully close ending point [ei] and thus the vowels are more distinct than in the General South African accent. An alternative realization of the former is an open-mid monophthong [ɛː]. Formerly, FACE was sometimes realized as a narrow diphthong [eɪ], but this has virtually disappeared by the 1990s. NEAR is phonemically distinct, normally as [iːə].[60]

In Geordie, the merger of FACE and NEAR is recessive and has never been categorical (SQUARE [ɛː] has always been a distinct vowel), as FACE can instead be pronounced as the closing diphthong [eɪ] or, more commonly, the close-mid front monophthong [eː]. The latter is the most common choice for younger speakers who tend to reject the centering diphthongs for FACE, which categorically undoes the merger for those speakers. Even when FACE is realized as an opening-centering diphthong, it may be distinguished from NEAR by the openness of the first element: [ɪə] or [eə] for FACE vs. [iə] for NEAR.[61][62][63]

Some of the words listed below may have different forms in traditional Geordie. For the sake of simplicity, the merged vowel is transcribed with ⟨eː⟩.

| /eɪ/ (from ME /aː/) | /eɪ/ (from other sources) | /eə/ | /ɪə/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | hay | hair | here | ˈeː | With h-dropping, in fully non-rhotic varieties. |

| A | hay | hare | here | ˈeː | With h-dropping, in fully non-rhotic varieties. |

| A | hey | hair | here | ˈeː | With h-dropping, in fully non-rhotic varieties. |

| A | hey | hare | here | ˈeː | With h-dropping, in fully non-rhotic varieties. |

| aid | aired | eared | ˈeːd | ||

| aid | hared | eared | ˈeːd | With h-dropping. | |

| bade | bared | beard | ˈbeːd | ||

| bade | bared | beered | ˈbeːd | ||

| bade | beared | beard | ˈbeːd | ||

| bade | beared | beered | ˈbeːd | ||

| base | Bierce | ˈbeːs | |||

| bass | Bierce | ˈbeːs | |||

| bay | bare | beer | ˈbeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| bay | bear | beer | ˈbeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| bays | bares | beers | ˈbeːz | ||

| bays | bears | beers | ˈbeːz | ||

| day | dare | dear | ˈdeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| days | dares | dears | ˈdeːz | ||

| days | theirs | dears | ˈdeːz | With th-stopping. | |

| days | there's | dears | ˈdeːz | With th-stopping. | |

| face | fierce | ˈfeːs | |||

| fade | fared | feared | ˈfeːd | ||

| fade | faired | feared | ˈfeːd | ||

| fay | fare | fear | ˈfeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| fay | fair | fear | ˈfeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| gay | gear | ˈɡeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | ||

| gaze | gays | gears | ˈɡeːz | ||

| hay | hair | here | ˈheː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| hay | hare | here | ˈheː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| haze | hays | airs | ears | ˈeːz | With h-dropping. |

| haze | hays | airs | here's | ˈeːz | With h-dropping. |

| haze | hays | hairs | ears | ˈeːz | With h-dropping. |

| haze | hays | hairs | here's | ˈheːz | |

| haze | hays | hares | ears | ˈeːz | With h-dropping. |

| haze | hays | hares | here's | ˈheːz | |

| haze | hays | heirs | ears | ˈeːz | With h-dropping. |

| haze | hays | heirs | here's | ˈeːz | With h-dropping. |

| hey | hair | here | ˈheː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| hey | hare | here | ˈheː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| jade | jeered | ˈdʒeːd | |||

| Kay | care | Keir | ˈkeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| Kay | care | kir | ˈkeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| may | mare | mere | ˈmeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| maze | maize | mares | Mears | ˈmeːz | |

| nay | near | ˈneː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | ||

| nays | nears | ˈneːz | |||

| paid | paired | peered | ˈpeːd | ||

| pay | pair | peer | ˈpeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| pay | pear | peer | ˈpeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| pays | pairs | peers | ˈpeːz | ||

| pays | pears | peers | ˈpeːz | ||

| raid | reared | ˈreːd | |||

| ray | rare | rear | ˈreː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| raze | raise | rears | ˈreːz | ||

| raze | rays | rears | ˈreːz | ||

| shade | shared | sheered | ˈʃeːd | ||

| shay | share | sheer | ˈʃeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| shays | shares | sheers | ˈʃeːz | ||

| spade | spared | speared | ˈspeːd | ||

| stade | staid | stared | steered | ˈsteːd | |

| stade | stayed | stared | steered | ˈsteːd | |

| stay | stare | steer | ˈsteː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| stays | stares | steers | ˈsteːz | ||

| they | their | ˈðeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | ||

| they | there | ˈðeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | ||

| they | they're | ˈðeː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | ||

| way | wear | Wear | ˈweː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| way | wear | we're | ˈweː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| way | where | Wear | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| way | where | we're | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| ways | wears | ˈweːz | |||

| ways | where's | ˈweːz | With the wine-whine merger. | ||

| weigh | wear | Wear | ˈweː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| weigh | wear | we're | ˈweː | In fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| weigh | where | Wear | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| weigh | where | we're | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| wade | weighed | where'd | ˈweːd | With the wine-whine merger. | |

| weighs | wears | ˈweːz | |||

| weighs | where's | ˈweːz | With the wine-whine merger. | ||

| whey | wear | Wear | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| whey | wear | we're | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| whey | where | Wear | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| whey | where | we're | ˈweː | With the wine-whine merger, in fully non-rhotic varieties. | |

| vase | veers | ˈveːz |

Father–farther and god–guard mergers

In Wells' terminology, the father–farther merger consists of the merger of the lexical sets PALM and START. It is found in the speech of the great majority of non-rhotic speakers, including those of England, Wales, the United States, the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. It may be absent in some non-rhotic speakers in the Bahamas.[52]

Minimal pairs are rare in accents without the father-bother merger. In non-rhotic British English (especially the varieties without the trap-bath split) and, to a lesser extent, Australian English, /ɑː/ most commonly corresponds to /ɑːr/ in American English, therefore it is most commonly spelled with ⟨ar⟩. In most non-rhotic American English (that includes non-rhotic Rhode Island, New York City,[64] some Southern U.S.,[65] and some African-American accents),[66] the spelling ⟨o⟩ is equally common in non-word-final positions due to the aforementioned father-bother merger. Those accents have the god-guard merger (a merger of LOT and START) in addition to the father–farther merger, yielding a three-way homophony between calmer (when pronounced without /l/), comma and karma, though minimal triplets like this are scarce.

The middle column (which only contains words with a preconsonantal vowel) participates in the merger only in the case of North American accents. In other accents, those words have a distinct vowel /ɒ/.

| /ɑː/ | /ɒ/ (in AmE) | /ɑːr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ah | N/A | are | ˈɑː | |

| ah | N/A | hour | ˈɑː | With smoothing. |

| ah | N/A | our | ˈɑː | With smoothing. |

| ah | N/A | R; ar | ˈɑː | |

| alms | arms | ˈɑːmz | ||

| alms | harms | ˈɑːmz | With H-dropping. | |

| Ana | honor | Arne | ˈɑːnə | |

| aunt | aren't | ˈɑːnt | With the trap-bath split. | |

| balmy | barmy | ˈbɑːmi | ||

| Bata | barter | ˈbɑːtə | ||

| bath | barf | ˈbɑːf | With the trap-bath split and th-fronting. | |

| bath | Bart | ˈbɑːt | With the trap-bath split and th-stopping. | |

| bob; Bob | barb; Barb | ˈbɑːb | ||

| bock | bark | ˈbɑːk | ||

| bocks | barks | ˈbɑːks | ||

| bocks | Berks | ˈbɑːks | ||

| bod | bard | ˈbɑːd | ||

| bod | barred | ˈbɑːd | ||

| boff | barf | ˈbɑːf | ||

| bot | Bart | ˈbɑːt | ||

| box | barks | ˈbɑːks | ||

| box | Berks | ˈbɑːks | ||

| calmer | comma | karma | ˈkɑːmə | Calmer can also be pronounced with /l/: /ˈkɑːlmə/. |

| calve | carve | ˈkɑːv | With the trap-bath split. | |

| cast | karst | ˈkɑːst | With the trap-bath split. | |

| caste | karst | ˈkɑːst | With the trap-bath split. | |

| cost | karst | ˈkɑːst | ||

| Chalmers | charmers | ˈtʃɑːməz | ||

| clock | Clark; Clarke | ˈklɑːk | ||

| clock | clerk | ˈklɑːk | ||

| cob | carb | ˈkɑːb | ||

| cod | card | ˈkɑːd | ||

| collar | Carla | ˈkɑːlə | ||

| collie | Carlie | ˈkɑːli | ||

| cop | carp | ˈkɑːp | ||

| cot | cart | ˈkɑːt | ||

| Dahmer | dharma | ˈdɑːmə | ||

| Dhaka | docker | darker | ˈdɑːkə | In American English. In the UK, Dhaka is /ˈdækə/. |

| dock | dark | ˈdɑːk | ||

| dollar | Darla | ˈdɑːlə | ||

| dolling | darling | ˈdɑːlɪŋ | ||

| don; Don | darn | ˈdɑːn | ||

| dot | dart | ˈdɑːt | ||

| fa | N/A | far | ˈfɑː | |

| fast | farced | ˈfɑːst | With the trap-bath split. | |

| father | farther | ˈfɑːðə | ||

| Ghana | gonna | Garner | ˈɡɑːnə | With the strong form of gonna (which can be /ˈɡɔːnə/ or /ˈɡoʊɪŋ tuː/ instead). |

| gob | garb | ˈɡɑːb | ||

| gobble | garble | ˈɡɑːbəl | ||

| god | garred | ˈɡɑːd | ||

| god | guard | ˈɡɑːd | ||

| Hamm | harm | ˈhɑːm | In American English. In the UK, Hamm is /ˈhæm/. | |

| hock | hark | ˈhɑːk | ||

| holly; Holly | Harley | ˈhɑːli | ||

| hominy | harmony | ˈhɑːməni | With the weak vowel merger. | |

| hop | harp | ˈhɑːp | ||

| hot | hart | ˈhɑːt | ||

| hot | heart | ˈhɑːt | ||

| hottie | hardy | ˈhɑːɾi | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. | |

| hottie | hearty | ˈhɑːɾi | Normally with intervocalic alveolar flapping. | |

| hough | hark | ˈhɑːk | ||

| hovered | Harvard | ˈhɑːvəd | ||

| Jah | N/A | jar | ˈdʒɑː | |

| Jahn | yarn | ˈjɑːn | ||

| Jan | yarn | ˈjɑːn | Jan can be /ˈjæn/ instead. | |

| Ka | N/A | car | ˈkɑː | |

| kava | carver | ˈkɑːvə | ||

| knock | narc | ˈnɑːk | ||

| knock | nark | ˈnɑːk | ||

| knocks | narcs | ˈnɑːks | ||

| knocks | narks | ˈnɑːks | ||

| Knox | narcs | ˈnɑːks | ||

| Knox | narks | ˈnɑːks | ||

| lava | larva | ˈlɑːvə | ||

| lock | lark | ˈlɑːk | ||

| Locke | lark | ˈlɑːk | ||

| lodge | large | ˈlɑːdʒ | ||

| lop | larp | ˈlɑːp | ||

| ma | N/A | mar | ˈmɑː | |

| mock | mark; Mark | ˈmɑːk | ||

| mocks | marks; Mark's | ˈmɑːks | ||

| mocks | Marx | ˈmɑːks | ||

| mod | marred | ˈmɑːd | ||

| modge | Marge | ˈmɑːdʒ | ||

| moll; Moll | marl | ˈmɑːl | ||

| molly; Molly | Marley | ˈmɑːli | ||

| mosh | marsh | ˈmɑːʃ | ||

| nock | narc | ˈnɑːk | ||

| nock | nark | ˈnɑːk | ||

| nocks | narcs | ˈnɑːks | ||

| nocks | narks | ˈnɑːks | ||

| Nox | narcs | ˈnɑːk | ||

| Nox | narks | ˈnɑːk | ||

| ox | arcs | ˈɑːks | ||

| ox | arks | ˈɑːks | ||

| pa | N/A | par | ˈpɑː | |

| Pali | polly; Polly | parley; Parley | ˈpɑːli | |

| Palma | Parma | ˈpɑːmə | ||

| palmer; Palmer | Parma | ˈpɑːmə | ||

| passed | parsed | ˈpɑːst | With the trap-bath split. | |

| past | parsed | ˈpɑːst | With the trap-bath split. | |

| path | part | ˈpɑːt | With the trap-bath split and th-stopping. | |

| pock | park; Park | ˈpɑːk | ||

| pocks | parks; Park's | ˈpɑːks | ||

| pot | part | ˈpɑːt | ||

| potch | parch | ˈpɑːtʃ | ||

| potty | party | ˈpɑːɾi | Normally with intervocalic alveolar flapping. | |

| pox | parks; Park's | ˈpɑːks | ||

| shod | shard | ˈʃɑːd | ||

| shock | shark | ˈʃɑːk | ||

| shop | sharp | ˈʃɑːp | ||

| shopping | sharpen | ˈʃɑːpən | With the weak vowel merger and G-dropping. | |

| ska | N/A | scar, SCAR | ˈskɑː | |

| sock | Sark | ˈsɑːk | ||

| sod | Sard | ˈsɑːd | ||

| spa | N/A | spar, SPAR | ˈspɑː | |

| Spock | spark | ˈspɑːk | ||

| spotter | Sparta | ˈspɑːɾə | Normally with intervocalic alveolar flapping. | |

| Stata | starter | ˈstɑːtə | ||

| stock | stark | ˈstɑːk | ||

| tod | tard | ˈtɑːd | ||

| tod | tarred | ˈtɑːd | ||

| Todd | tard | ˈtɑːd | ||

| Todd | tarred | ˈtɑːd | ||

| top | tarp | ˈtɑːp | ||

| tot | tart | ˈtɑːt | ||

| yon | yarn | ˈjɑːn |

Goat–cure merger

The goat–cure merger is a variable and recessive merger of /oː/ and /uə/ (the vowels corresponding to /əʊ/ and /ʊə/ in RP) found in Geordie. It is not categorical, as GOAT can instead be pronounced as the close-mid monophthongs [oː] and [ɵː]. The central [ɵː] is as stereotypically Geordie as the merger itself, though it is still used alongside [oː] by young, middle-class males who, as younger speakers in general, reject the centering diphthongs for /oː/. This categorically undoes the merger for those speakers.[67][68]

Even when GOAT is realized as an opening-centering diphthong, it may be distinguished from CURE by the openness of the first element: [ʊə] or [oə] vs. [uə].[61][62][69]

| /oː/ | /uə/ | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| toe | tour | ˈtuə |

| tow | tour | ˈtuə |

Pawn–porn and caught–court mergers

In Wells' terminology, the pawn–porn merger consists of the merger of the lexical sets THOUGHT and NORTH. It is found in most of the same accents as the father–farther merger described above, but is absent from the Bahamas and Guyana.[52]

Labov et al. suggest that, in New York City English, this merger is present in perception not production. As in, although even locals perceive themselves using the same vowel in both cases, they tend to produce the NORTH/FORCE vowel higher and more retracted than the vowel of THOUGHT.[70]

Most speakers with the pawn-porn merger also have the same vowels in caught and court (a merger of THOUGHT and FORCE), yielding a three-way merger of awe-or-ore/oar (see horse-hoarse merger). These include the accents of Southern England, non-rhotic New York City speakers, Trinidad and the Southern hemisphere.

The lot-cloth split coupled with those mergers produces a few more homophones, such as boss–bourse. Specifically, the phonemic merger of the words often and orphan was a running gag in the Gilbert and Sullivan musical, The Pirates of Penzance.

In cockney and some Estuary English the merged THOUGHT-NORTH-FORCE vowel has split into what can be analyzed as two separate phonemes which Wells writes /oː/ and /ɔə/ - see THOUGHT split.

| /ɔː/ | /ɔːr/ | /oʊr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alk | orc | ˈɔːk | ||

| auk | orc | ˈɔːk | ||

| aw | or | oar | ˈɔː | |

| aw | or | ore | ˈɔː | |

| awe | or | oar | ˈɔː | |

| awe | or | ore | ˈɔː | |

| awk | orc | ˈɔːk | ||

| balk | bork | ˈbɔːk | ||

| baud | board | ˈbɔːd | ||

| baud | bored | ˈbɔːd | ||

| bawd | board | ˈbɔːd | ||

| bawd | bored | ˈbɔːd | ||

| bawn | born | borne | ˈbɔːn | |

| bawn | born | bourn(e) | ˈbɔːn | |

| boss | bourse | ˈbɔːs | With the lot-cloth split. | |

| caught | court | ˈkɔːt | ||

| caulk | cork | ˈkɔːk | ||

| caw | core | ˈkɔː | ||

| cawed | chord | ˈkɔːd | ||

| cawed | cord | ˈkɔːd | ||

| daw | door | ˈdɔː | ||

| draw | drawer | ˈdrɔː | ||

| flaw | floor | ˈflɔː | ||

| fought | fort | ˈfɔːt | ||

| gaud | gored | ˈɡɔːd | ||

| gnaw | nor | ˈnɔː | ||

| haw | whore | ˈhɔː | ||

| hawk | orc | ˈɔːk | With H-dropping. | |

| hoss[71] | horse | ˈhɔːs | With the lot-cloth split. | |

| laud | lord | ˈlɔːd | ||

| law | lore | ˈlɔː | ||

| lawed | lord | ˈlɔːd | ||

| lawn | lorn | ˈlɔːn | ||

| maw | more | ˈmɔː | ||

| maw | Moore | ˈmɔː | ||

| moss | Morse | ˈmɔːs | With the lot-cloth split. | |

| off | Orff; orfe; orf | ˈɔːf | With the lot-cloth split. | |

| often | orphan | ˈɔːfən | With the lot-cloth split. "Often" is pronounced with a sounded T by some speakers. | |

| paw | pore | ˈpɔː | ||

| paw | pour | ˈpɔː | ||

| pawn | porn | ˈpɔːn | ||

| raw | roar | ˈrɔː | ||

| sauce | source | ˈsɔːs | ||

| saw | soar | ˈsɔː | ||

| saw | sore | ˈsɔː | ||

| sawed | soared | ˈsɔːd | ||

| sawed | sword | ˈsɔːd | ||

| Sean | shorn | ˈʃɔːn | ||

| shaw | shore | ˈʃɔː | ||

| Shawn | shorn | ˈʃɔːn | ||

| sought | sort | ˈsɔːt | ||

| stalk | stork | ˈstɔːk | ||

| talk | torque | ˈtɔːk | ||

| taught | tort | ˈtɔːt | ||

| taut | tort | ˈtɔːt | ||

| taw | tor | tore | ˈtɔː | |

| thaw | Thor | ˈθɔː | ||

| yaw | yore | ˈjɔː | ||

| yaw | your | ˈjɔː | Your can be /ˈjʊə/ instead. |

Paw–poor merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets THOUGHT and CURE. It is found in those non-rhotic accents containing the caught–court merger that have also undergone the pour–poor merger. Wells lists it unequivocally only for the accent of Trinidad, but it is an option for non-rhotic speakers in England, Australia and New Zealand. Such speakers have a potential four-way merger taw–tor–tore–tour.[72]

| /ɔː/ | /ʊər/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| gaud | gourd | ˈɡɔːd | |

| haw | whore | ˈhɔː | |

| law | lure | ˈlɔː | With yod-dropping. |

| maw | moor | ˈmɔː | |

| maw | Moore | ˈmɔː | |

| paw | poor | ˈpɔː | |

| shaw | sure | ˈʃɔː | |

| taw | tour | ˈtɔː | |

| tawny | tourney | ˈtɔːni | |

| yaw | your | ˈjɔː | |

| yaw | you're | ˈjɔː |

Shot–short merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets LOT and NORTH. It may be present in some Eastern New England accents[73][74] and Singapore English.

| /ɒ/ | /ɒr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| bon | born | ˈbɒːn | |

| box | borks | ˈbɒːks | |

| cock | cork; Cork | ˈkɒːk | |

| cocks | corks; Cork's | ˈkɒːks | |

| cops | corpse | ˈkɒːps | |

| cox | corks; Cork's | ˈkɒːks | |

| cod | chord | ˈkɒːd | |

| cod | cord | ˈkɒːd | |

| con | corn | ˈkɒːn | |

| dock | dork | ˈdɒːk | |

| fox | forks | ˈfɒːks | |

| dom | dorm | ˈdɒːm | |

| mog | morgue | ˈmɒːɡ | |

| mot | Mort | ˈmɒːt | |

| not | north | ˈnɒːt | With Th-stopping. |

| odder | order | ˈɒːɾə | Normally with intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| otter | order | ˈɒːɾə | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| ox | orcs | ˈɒːks | |

| pond | porned | ˈpɒːnd | |

| pock | pork | ˈpɒːk | |

| posh | Porsche | ˈpɒːʃ | |

| pot | port | ˈpɒːt | |

| scotch; Scotch | scorch | ˈskɒːtʃ | |

| shoddy | shorty | ˈʃɒːɾi | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| shot | short | ˈʃɒːt | |

| snot | snort | ˈsnɒːt | |

| sob | Sorb | ˈsɒːb | |

| solder | sorter | ˈsɒːɾə | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| sot | sort | ˈsɒːt | |

| Spock | spork | ˈspɒːk | |

| spot | sport | ˈspɒːt | |

| stock | stork | ˈstɒːk | |

| swan | sworn | ˈswɒːn | |

| swat | swart | ˈswɒːt | |

| tock | torque | ˈtɒːk | |

| tot | tort | ˈtɒːt | |

| tox | torques | ˈtɒːks | |

| wabble | warble | ˈwɒːbəl | |

| wad | ward | ˈwɒːd | |

| wad | warred | ˈwɒːd | |

| wan | warn | ˈwɒːn | |

| wand | warned | ˈwɒːnd | |

| wanna | Warner | ˈwɒːnə | |

| watt | wart | ˈwɒːt | |

| whap | warp | ˈwɒːp | With wine–whine merger. |

| what | wart | ˈwɒːt | With wine–whine merger. |

| whop | warp | ˈwɒːp | With wine–whine merger. |

| wobble | warble | ˈwɒːbəl | |

| yock | York | ˈjɒːk |

Show–sure merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets GOAT and CURE. It may be present in those speakers who have both the dough–door merger described above, and also the pour–poor merger. These include some southern U.S. non-rhotic speakers, some speakers of African-American English and some speakers in Guyana.[52] It can be seen in the term "Fo Sho", an imitation of "for sure".

| /oʊ/ | /ʊər/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| beau | Boer | ˈboʊ | |

| beau | boor | ˈboʊ | |

| bow | Boer | ˈboʊ | |

| bow | boor | ˈboʊ | |

| goad | gourd | ˈɡoʊd | |

| hoe | whore | ˈhoʊ | |

| lo | lure | ˈloʊ | With yod-dropping. |

| low | lure | ˈloʊ | With yod-dropping. |

| Moe | moor | ˈmoʊ | |

| Moe | Moore | ˈmoʊ | |

| mode | moored | ˈmoʊd | |

| mow | moor | ˈmoʊ | |

| mow | Moore | ˈmoʊ | |

| mowed | moored | ˈmoʊd | |

| Po | poor | ˈpoʊ | |

| Poe | poor | ˈpoʊ | |

| roe | Ruhr | ˈroʊ | |

| row | Ruhr | ˈroʊ | |

| shew | sure | ˈʃoʊ | |

| show | sure | ˈʃoʊ | |

| toad | toured | ˈtoʊd | |

| toe | tour | ˈtoʊ | |

| toed | toured | ˈtoʊd | |

| tow | tour | ˈtoʊ | |

| towed | toured | ˈtoʊd | |

| yo | your | ˈjoʊ | |

| yo | you're | ˈjoʊ |

Up-gliding NURSE

Up-gliding NURSE is a diphthongized vowel sound, [əɪ], used as the pronunciation of the NURSE phoneme /ɜ/. This up-gliding variant historically occurred in some non-rhotic dialects of American English and is particularly associated with the early twentieth-century (but now extinct or moribund) dialects of New York City, New Orleans, and Charleston,[75] likely developing in the prior century. In fact, in speakers born before World War I, this sound apparently predominated throughout older speech of the Southern United States, ranging from "South Carolina to Texas and north to eastern Arkansas and the southern edge of Kentucky."[76] This variant happened only before a consonant, so, for example, stir was never [stəɪ];[77] rather stir would have been pronounced [stɜ(r)].

Coil–curl merger

In some cases, particularly in New York City, the NURSE sound gliding from a schwa upwards even led to a phonemic merger of the vowel classes associated with the General American phonemes /ɔɪ/ as in CHOICE with the /ɜr/ of NURSE; thus, words like coil and curl, as well as voice and verse, were homophones. The merged vowel was typically a diphthong [əɪ], with a mid central starting point, rather than the back rounded starting point of /ɔɪ/ of CHOICE in most other accents of English. The merger is responsible for the "Brooklynese" stereotypes of bird sounding like boid and thirty-third sounding like toity-toid. This merger is known for the word soitanly, used often by the Three Stooges comedian Curly Howard as a variant of certainly in comedy shorts of the 1930s and 1940s. The songwriter Sam M. Lewis, a native New Yorker, rhymed returning with joining in the lyrics of the English-language version of Gloomy Sunday. Except for New Orleans English,[78][79][80] this merger did not occur in the South, despite up-gliding NURSE existing in some older Southern accents; instead, a distinction between the two phonemes was maintained due to a down-gliding CHOICE sound: something like [ɔɛ].

In 1966, according to a survey that was done by William Labov in New York City, 100% of the people over 60 used [əɪ] for bird. With each younger age group, however, the percentage got progressively lower: 59% of 50- to 59-year-olds, 33% of 40- to 49-year-olds, 24% of 20- to 39-year-olds, and finally, only 4% of people 8–19 years old used [əɪ]. Nearly all native New Yorkers born since 1950, even those whose speech is otherwise non-rhotic, now pronounce bird as [bɝd].[81] However, Labov reports this vowel to be slightly raised compared to other dialects.[82]

| /ɔɪ/ | /ɜːr/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| adjoin | adjourn | əˈdʒəɪn | |

| boil | burl | ˈbəɪl | |

| Boyd | bird | ˈbəɪd | |

| Boyle | burl | ˈbəɪl | |

| coil | curl | ˈkəɪl | |

| coin | kern | ˈkəɪn | |

| coitus | Curtis | ˈkəɪɾəs | With weak vowel merger, normally with intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| foil | furl | ˈfəɪl | |

| goitre; goiter | girder | ˈɡəɪɾər | With intervocalic alveolar flapping. |

| hoist | Hearst | ˈhəɪst | |

| hoist | hurst; Hurst | ˈhəɪst | |

| Hoyle | hurl | ˈhəɪl | |

| loin | learn | ˈləɪn | |

| oil | earl | ˈəɪl | |

| poil | pearl | ˈpəɪl | |

| poise | purrs | ˈpəɪz | |

| toyed | turd | ˈtəɪd | |

| voice | verse | ˈvəɪs | |

| Voight | vert | ˈvəɪt |

Effect of non-rhotic dialects on orthography

Certain words have spellings derived from non-rhotic dialects or renderings of foreign words through non-rhotic pronunciation. In rhotic dialects, spelling pronunciation has caused these words to be pronounced rhotically anyway. Examples include:

- Er, used in non-rhotic dialects to indicate a filled pause, which most rhotic dialects would instead convey with uh or eh.

- The game Parcheesi, from Indian Pachisi.

- British English slang words:

- char for cha from the Mandarin Chinese pronunciation of Chinese: 茶 (= "tea" (the drink))

- In Rudyard Kipling's books:

- The donkey Eeyore in A.A. Milne's stories, whose name comes from the sound that donkeys make, commonly spelled hee-haw in American English.

- Burma and Myanmar for Burmese [bəmà] and [mjàmmà]

- Orlu for Igbo [ɔ̀lʊ́]

- Transliteration of Cantonese words and names, such as char siu (Chinese: 叉燒; Jyutping: caa¹ siu¹) and Wong Kar-wai (Chinese: 王家衞; Jyutping: Wong⁴ Gaa1wai⁶)

- The spelling of schoolmarm for school ma'am, which Americans pronounce with the rhotic consonant.

- The spelling Park for the Korean surname 박 (pronounced [pak]), which does not contain a liquid consonant in Korean.

Notes

References

- Paul Skandera, Peter Burleigh, A Manual of English Phonetics and Phonology, Gunter Narr Verlag, 2011, p. 60.

- Lass (1999), p. 114.

- Wells (1982), p. 216.

- Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006): 47.

- Gick (1999:31), citing Kurath (1964)

- Labov, Ash, and Boberg, 2006: pp. 47–48.

- Lass (1999), p. 115.

- Fisher (2001), p. 76.

- Fisher (2001), p. 77.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), pp. 5, 47.

- Based on H. Orton, et al., Survey of English Dialects (1962–71). Some areas with partial rhoticity, such as parts of the East Riding of Yorkshire, are not shaded on this map.

- Based on P. Trudgill, The Dialects of England.

- Lass (1999), pp. 114–15.

- Original French: "...dans plusieurs mots, l'r devant une consonne est fort adouci, presque muet, & rend un peu longue la voyale qui le precede". Lass (1999), p. 115.

- Fisher (2001), p. 73.

- Gordon, Elizabeth; Campbell, Lyle; Hay, Jennifer; Maclagan, Margaret; Sudbury, Peter; Trudgill, Andrea, eds. (2004). New Zealand English: Its Origins and Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 174.

- Aveyard, Edward (2019). "Berliner Lautarchiv: the Wakefield Sample". Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society. pp. 1–5.

- Wells, Accents of English, 1:224-225.

- Gimson, Alfred Charles (2014), Cruttenden, Alan (ed.), Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.), Routledge, pp. 119–120, ISBN 978-1-4441-8309-2

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- Wells, J. C. (1995). Accents of English 1: An Introduction. Gateshead: Cambridge University Press. p. 201.

- Wells, Accents of English, p. 490.

- Wakelyn, Martin: "Rural dialects in England", in: Trudgill, Peter (1984): Language in the British Isles, p.77

- Wells, J. C. (1982). Accents of English 3: Beyond the British Isles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 629. ISBN 0-521-28541-0.

- Mesthrie, Rajend; Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W., eds. (18 January 2008), "Pakistani English: phonology", Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Mouton de Gruyter, doi:10.1515/9783110208429.1.244, ISBN 9783110208429, retrieved 16 April 2019

- Wells, Accents of English, pp. 76, 221

- Schneider, Edgar (2008). Varieties of English: The Americas and the Caribbean. Walter de Gruyter. p. 396.

- McClear, Sheila (2 June 2010). "Why the classic Noo Yawk accent is fading away". New York Post. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Stuart-Smith, Jane (1999). "Glasgow: accent and voice quality". In Foulkes, Paul; Docherty, Gerard (eds.). Urban Voices. Arnold. p. 210. ISBN 0-340-70608-2.

- Trudgill, Peter (1984). Language in the British Isles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28409-7.

- Milla, Robert McColl (2012). English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-7486-4181-9.

- Trudgill, Peter (2010). Investigations in Sociohistorical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

- Gick, Bryan. 1999. A gesture-based account of intrusive consonants in English Archived 12 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Phonology 16: 1, pp. 29–54. (pdf). Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- Harris 2006: pp. 2–5.

- Pollock et al., 1998.

- Thomas, Erik R. "Rural white Southern accents" (PDF). p. 16. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Trudgill, Peter (2000). "Sociohistorical linguistics and dialect survival: a note on another Nova Scotian enclave". In Magnus Leung (ed.). Language Structure and Variation. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. p. 197.

- Hickey, Raymond (1999). "Dublin English: current changes and their motivations". In Foulkes, Paul; Docherty, Gerard (eds.). Urban Voices. Arnold. p. 272. ISBN 0-340-70608-2.

- Demirezen, Mehmet (2012). "Which /r/ are you using as an English teacher? rhotic or non-rhotic?" (PDF). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier. 46: 2659–2663. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.542. ISSN 1877-0428. OCLC 931520939.

- Salbrina, S.; Deterding, D. (2010). "Rhoticity in Brunei English". English World-Wide. 31: 121–137.

- Nur Raihan Mohamad (2017). "Rhoticity in Brunei English : A diachronic approach". Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 17: 1–7.

- Gupta, Anthea F.; Hiang, Tan Chor (January 1992). "Post-Vocalic /r/ in Singapore English" (PDF). York Papers in Linguistics. 16: 139–152. ISSN 0307-3238. OCLC 2199758.

- Brinton, Lauren and Leslie Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford University Press: Canada, 2006

- Bowerman (2004), p. 940.

- Lass (2002), p. 121.

- Sutton, Peter (1989). "Postvocalic R in an Australian English dialect". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 9 (1).

- Clark, L., "Southland dialect study to shed light on language evolution," New Zealand Herald, 9 Dec 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "5. – Speech and accent – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 5 September 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Bauer & Warren (2004), p. 594.

- Hogg, R.M., Blake, N.F., Burchfield, R., Lass, R., and Romaine, S., (eds.) (1992) The Cambridge history of the English language. (Volume 5) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521264785 p. 387. Retrieved from Google Books.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22919-7., pp. 136–37, 203–6, 234, 245–47, 339–40, 400, 419, 443, 576

- Wells (1982)

- Wells (1982), p. 225

- Upton, Clive; Eben Upton (2004). Oxford rhyming dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-19-280115-5.

- Upton, Clive; Eben Upton (2004). Oxford rhyming dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-19-280115-5.

- Devonish & Harry (2004), pp. 460, 463, 476.

- Trudgill (2004), pp. 170, 172.

- Lass (1990), pp. 277–279.

- Bowerman (2004), p. 938.

- Collins & Mees (1990), pp. 92–93, 95–97.

- Watt (2000), p. 72.

- Watt & Allen (2003), pp. 268–269.

- Beal (2004), pp. 123, 126.

- Wells (1982), p. 504

- Wells (1982), p. 544

- Wells (1982), p. 577

- Watt & Allen (2003), p. 269.

- Beal (2004), pp. 123–124.

- Beal (2004), p. 126.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 235

- Dialectal variant of "horse"

- Wells, p. 287

- Wells, p. 520

- Dillard, Joey Lee (1980). Perspectives on American English. The Hague; New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 90-279-3367-7.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 259

- Thomas (2006), p. 8

- Wells (1982), pp. 508 ff

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006), p. 260

- Canatella, Ray (2011). The YAT Language of New Orleans. iUniverse. pp. 67, ... ISBN 978-1-4620-3295-2.

MOYCHANDIZE – Translation: Merchandise. "Dat store seem to be selling nutin' but cheap moychandize"

- Trawick-Smith, Ben (1 September 2011). "On the Hunt for the New Orleans Yat". Dialect Blog. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Labov (1966)

- Labov (1966), p. 216

Bibliography

- Beal, Joan (2004), "English dialects in the North of England: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 113–133, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Bowerman, Sean (2004), "White South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 931–942, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (1990), "The Phonetics of Cardiff English", in Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (eds.), English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change, Multilingual Matters Ltd., pp. 87–103, ISBN 1-85359-032-0

- Fisher, John Hurt (2001). "British and American, Continuity and Divergence". In Algeo, John (ed.). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume VI: English in North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–85. ISBN 0-521-26479-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gick, Bryan (1999). "A gesture-based account of intrusive consonants in English" (PDF). Phonology. 16 (1): 29–54. doi:10.1017/s0952675799003693. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurath, H. (1964). A Phonology and Prosody of Modern English. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lass, Roger (1990), "A 'standard' South African vowel system", in Ramsaran, Susan (ed.), Studies in the Pronunciation of English: A Commemorative Volume in Honour of A.C. Gimson, Routledge, pp. 272–285, ISBN 978-0-41507180-2

- Lass, Roger (1999). "Phonology and Morphology". In Lass, Roger (ed.). The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III: 1476–1776. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–186. ISBN 0-521-26476-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pollock, Bailey, Berni, Fletcher, Hinton, Johnson, Roberts, & Weaver (17 March 2001). "Phonological Features of African American Vernacular English (AAVE)". Retrieved 8 November 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Trudgill, Peter (1984). Language in the British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Trudgill, Peter (2004), "The dialect of East Anglia: Phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 163–177, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Watt, Dominic (2000), "Phonetic parallels between the close–mid vowels of Tyneside English: Are they internally or externally motivated?", Language Variation and Change, 12 (1): 69–101, doi:10.1017/S0954394500121040

- Watt, Dominic; Allen, William (2003), "Tyneside English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 267–271, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001397

- Wells, J. C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)