Bengali phonology

The phonology of Bengali, like that of its neighbouring Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, is characterised by a wide variety of diphthongs and inherent back vowels (both /o/ and /ɔ/). /ɔ/ corresponds to and developed out of the Sanskrit schwa, which is retained as such by almost all other branches of the Indo-Aryan language family.

Phonemic inventory

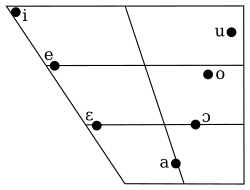

Phonemically, Bengali features 29 consonants and 7 vowels. Each vowel has examples of being nasalized in Bengali words, thus adding 7 more additional nasalized vowels. In the tables below, the sounds are given in IPA.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e[lower-alpha 1] | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ[lower-alpha 1] | ɔ | |

| Open | a[lower-alpha 2] |

| Labial | Dental, Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palato- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Plosive / Affricate | voiceless unaspirated | p | t | ʈ[lower-alpha 3] | tʃ | k | |

| voiceless aspirated | pʰ[lower-alpha 4] | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | ||

| voiced unaspirated | b | d | ɖ[lower-alpha 3] | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| voiced aspirated (murmured)[lower-alpha 5] | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| Fricative | (f)[lower-alpha 4] | s,[lower-alpha 6] (z)[lower-alpha 7] | ʃ | h~ɦ[lower-alpha 8] | |||

| Approximant | l | ||||||

| Rhotic | ɾ~r[lower-alpha 9] | ɽ,[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 10] (ɽʰ) | |||||

Although the standard form of Bengali is largely uniform across West Bengal and Bangladesh, there are a few sounds that vary in pronunciation (in addition to the myriad variations in non-standard dialects):

- /æ/ can occur as an allophone of either /ɛ/ or /e/ depending on the speaker or variety.[1]

- Although most transcriptions use /a/, it is phonetically realised as a near-open central vowel [ɐ] by most speakers.

- True retroflex (murdhonno) consonants are not found in Bengali.[2] They are apical postalveolar in Western Dialects. In other dialects, they are fronted to apical alveolar.

- /pʰ/ (written as ⟨ফ⟩) is phonetically realised as either [pʰ] or a voiceless labial fricative [f].

- The murmured series is missing in the Eastern Bengali of Dhaka and in Chittagong Bengali, where it is replaced by tone, as in Punjabi.[3]

- /s/ is a phoneme for many speakers of Standard Bengali (e.g. সিরকা /sirka/ 'vinegar', অস্থির /ɔstʰir/ 'uneasy', ব্যস /bas/ or /bɛs/ 'enough'). For most speakers, /s/ and /ʃ/ are phonemically distinct (আস্তে /aste/ 'softly' vs. আসতে /aʃte/ 'to come'). For some, especially in Rajshahi, there is no difference between স and শ, (বাস /bas/ 'bus' vs. বাঁশ /bas/ 'bamboo'); they have the same consonant sound. For some speakers, [s] can be analyzed as an allophone of either /ʃ/ or /tʃʰ/ ([ʃalam] for সালাম [salam] 'greetings' or বিচ্ছিরি [bitʃːʰiri] for বিশ্রী [bisːri] 'ugly'). Some words that originally had /s/ are now pronounced with [tʃʰ] in Standard Bengali (পছন্দ pochondo [pɔtʃʰondo] 'like', compared to Persian pasand).

- /z/: ⟨জ⟩ and ⟨য⟩ may represent a voiced affricate /dʒ/ in Standard Bengali words of native origin, but they can also represent /z/ in foreign words and names (জাকাত [zakat] 'zakah charity', আজিজ [aziz] 'Aziz'). Many speakers replace /z/ with /dʒ/. However, a native s/z opposition has developed in Chittagonian Bengali. Additionally, Some words that originally had /z/ are now pronounced with [dʑ] in Standard Bengali (সবজি [ɕobdʑi] 'vegetable', from Persian sabzi).

- /ɦ/: /h/ occurs in word-initial or final positions while /ɦ/ occurs medially.

- /r/: The Voiced Alveolar Trill [r] occurs word-initially; as against to Voiced Alveolar Flap [ɾ], which occurs medially and finally.

- /ɽ/: In the form of Standard Bengali spoken in Dhaka, /r/ and /ɽ/ are often indistinct phonemically, and thus the pairs পড়ে /pɔɽe/ 'reads'/'falls' vs. পরে /pɔɾe/ 'wears'/'after', and করা /kɔɾa/ 'do' vs. কড়া [kɔɽa] 'strict' can be homophonous.

Consonant clusters

Native Bengali (তদ্ভব tôdbhôbo) words do not allow initial consonant clusters;[4] the maximum syllabic structure is CVC (i.e. one vowel flanked by a consonant on each side). Many speakers of Bengali restrict their phonology to this pattern, even when using Sanskrit or English borrowings, such as গেরাম geram (CV.CVC) for গ্রাম gram (CCVC) meaning 'village' or ইস্কুল iskul / ishkul (VC.CVC) for স্কুল skul (CCVC) 'school'.

Sanskrit (তৎসম tôtshômo) words borrowed into Bengali, however, possess a wide range of clusters, expanding the maximum syllable structure to CCCVC. Some of these clusters, such as the [mr] in মৃত্যু mrittü ('death') or the [sp] in স্পষ্ট spôshṭo ('clear'), have become extremely common, and can be considered permitted consonant clusters in Bengali. English and other foreign (বিদেশী bideshi) borrowings add even more cluster types into the Bengali inventory, further increasing the syllable capacity, as commonly-used loanwords such as ট্রেন ṭren ('train') and গ্লাস glash ('glass') are now included in leading Bengali dictionaries.

Final consonant clusters are rare in Bengali.[5] Most final consonant clusters were borrowed into Bengali from English, as in লিফ্ট lifṭ ('elevator') and ব্যাংক beņk ("bank'). However, final clusters do exist in some native Bengali words, although rarely in standard pronunciation. One example of a final cluster in a standard Bengali word would be গঞ্জ gônj, which is found in names of hundreds of cities and towns across Bengal, including নবাবগঞ্জ Nôbabgônj and মানিকগঞ্জ Manikgônj. Some nonstandard varieties of Bengali make use of final clusters quite often. For example, in some Purbo (eastern) dialects, final consonant clusters consisting of a nasal and its corresponding oral stop are common, as in চান্দ chand ('moon'). The Standard Bengali equivalent of chand would be চাঁদ chãd, with a nasalized vowel instead of the final cluster.

Diphthongs

| IPA | Transliteration | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /ii̯/ | ii | nii "I take" |

| /iu̯/ | iu | biubhôl "upset" |

| /ei̯/ | ei | dei "I give" |

| /eu̯/ | eu | ḍheu "wave" |

| /ɛe̯/ | ee | nee "(s)he takes" |

| /ai̯/ | ai | pai "I find" |

| /ae̯/ | ae | pae "(s)he finds" |

| /au̯/ | au | pau "sliced bread" |

| /ao̯/ | ao | pao "you find" |

| /ɔe̯/ | ôe | nôe "(s)he is not" |

| /ɔo̯/ | ôo | nôo "you are not" |

| /oi̯/ | oi | noi "I am not" |

| /oo̯/ | oo | dhoo "you wash" |

| /ou̯/ | ou | nouka "boat" |

| /ui̯/ | ui | dhui "I wash" |

Magadhan languages such as Bengali are known for their wide variety of diphthongs, or combinations of vowels occurring within the same syllable.[6] Several vowel combinations can be considered true monosyllabic diphthongs, made up of the main vowel (the nucleus) and the trailing vowel (the off-glide). Almost all other vowel combinations are possible, but only across two adjacent syllables, such as the disyllabic vowel combination [u.a] in কুয়া kua ('well'). As many as 25 vowel combinations can be found, but some of the more recent combinations have not passed through the stage between two syllables and a diphthongal monosyllable.[7]

Prosody

Stress

In standard Bengali, stress is predominantly initial. Bengali words are virtually all trochaic; the primary stress falls on the initial syllable of the word, while secondary stress often falls on all odd-numbered syllables thereafter, giving strings such as সহযোগিতা shôhojogita [ˈʃɔhoˌdʒoɡiˌta] ('cooperation'). The first syllable carries the greatest stress, with the third carrying a somewhat weaker stress, and all following odd-numbered syllables carrying very weak stress. However, in words borrowed from Sanskrit, the root syllable has stress, out of harmony with the situation with native Bengali words.[8] Also, in a declarative sentence, the stress is generally lowest on the last word of the sentence.

Adding prefixes to a word typically shifts the stress to the left; for example, while the word সভ্য shobbho [ˈʃobbʱo] ('civilized') carries the primary stress on the first syllable, adding the negative prefix /ɔ-/ creates অসভ্য ôshobbho [ˈɔʃobbʱo] ('uncivilized'), where the primary stress is now on the newly added first syllable অ ô. Word-stress does not alter the meaning of a word and is always subsidiary to sentence-level stress.[8]

Intonation

For Bengali words, intonation or pitch of voice have minor significance, apart from a few cases such as distinguishing between identical vowels in a diphthong. However, in sentences intonation does play a significant role.[9] In a simple declarative sentence, most words and/or phrases in Bengali carry a rising tone,[10] with the exception of the last word in the sentence, which only carries a low tone. This intonational pattern creates a musical tone to the typical Bengali sentence, with low and high tones alternating until the final drop in pitch to mark the end of the sentence.

In sentences involving focused words and/or phrases, the rising tones only last until the focused word; all following words carry a low tone.[10] This intonation pattern extends to wh-questions, as wh-words are normally considered to be focused. In yes-no questions, the rising tones may be more exaggerated, and most importantly, the final syllable of the final word in the sentence takes a high falling tone instead of a flat low tone.[11]

Vowel length

Like most Magadhan languages, vowel length is not contrastive in Bengali; all else equal, there is no meaningful distinction between a "short vowel" and a "long vowel",[12] unlike the situation in most Indo-Aryan languages. However, when morpheme boundaries come into play, vowel length can sometimes distinguish otherwise homophonous words. This is because open monosyllables (i.e. words that are made up of only one syllable, with that syllable ending in the main vowel and not a consonant) can have somewhat longer vowels than other syllable types.[13] For example, the vowel in ca ('tea') can be somewhat longer than the first vowel in caṭa ('licking'), as ca is a word with only one syllable, and no final consonant. The suffix ṭa ('the') can be added to ca to form caṭa ('the tea'), and the long vowel is preserved, creating a minimal pair ([ˈtʃaʈa] vs. [ˈtʃaˑʈa]). Knowing this fact, some interesting cases of apparent vowel length distinction can be found. In general, Bengali vowels tend to stay away from extreme vowel articulation.[13]

Furthermore, using a form of reduplication called "echo reduplication", the long vowel in ca can be copied into the reduplicant ṭa, giving caṭa ('tea and all that comes with it'). Thus, in addition to caṭa ('the tea') with a longer first vowel and caṭa ('licking') with no long vowels, we have caṭa ('tea and all that comes with it') with two longer vowels.

Regional phonological variations

The phonological alternations of Bengali vary greatly due to the dialectal differences between the speech of Bengalis living on the পশ্চিম Poschim (western) side and পূর্ব Purbo (eastern) side of the Padma River.

Fricatives

In the dialects prevalent in much of eastern Bangladesh (Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka and Sylhet divisions), many of the stops and affricates heard in Kolkata Bengali are pronounced as fricatives.

The aspirated velar stop খ [kʰ] and the aspirated labial stop ফ [pʰ] of Poshcim Bengali correspond to খ় [x~ʜ] and ফ় [f] or [ɸ] in many dialects of Purbo Bengali. These pronunciations are more prevalent in the Sylheti dialect of northeastern Bangladesh—the dialect of Bengali most common in the United Kingdom.

Many Purbo Bengali dialects share phonological features with Assamese, including the debuccalization of শ [ɕ] to হ [h] or খ় [x].[14]

Tibeto-Burman influence

The influence of Tibeto-Burman languages on the phonology is mostly on the Bengali spoken in east of the Padma River and relatively less in West and South Bengal, as is seen by the lack of nasalized vowels in eastern Bengal, but nasalization is present in Indian Bengali and an alveolar articulation for the otherwise postalveolar stops ট [t̠], ঠ [t̠ʰ], ড [d̠], and ঢ [d̠ʱ], resembling the equivalent phonemes in languages such as Thai and Lao.

In the phonology of West and Southern Bengal, the distinction between র [r] and ড়/ঢ় [ɽ] is clear and distinct like neighbouring Indian languages. However, in the far eastern variants, Tibeto-Burman influence makes the distinction less clear, and it sometimes becomes similar to the phonology of the Assamese ৰ rô [ɹ].[14] Unlike most languages of the region, Purbo Bengali dialects tend not to distinguish aspirated voiced stops ঘ [ɡʱ], ঝ [dʑʱ], ঢ [d̠ʱ], ধ [dʱ], and ভ [bʱ] from their unaspirated equivalents, with some dialects treating them as allophones of each other and other dialects replacing the former with the latter completely.

Some variants of Bengali, particularly Chittagonian and Chakma Bengali, have contrastive tone and so differences in pitch can distinguish words. There is also a distinction between ই and ঈ in many northern Bangladeshi dialects. ই represents the uncommon [ɪ], but ঈ the standard [i] used for both letters in most other dialects.

References

- "Bengali romanization table" (PDF). Bahai Studies. Bahai Studies. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Mazumdar, Bijaychandra (2000). The history of the Bengali language (Repr. [d. Ausg.] Calcutta, 1920. ed.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 57. ISBN 978-8120614529.

yet it is to be noted as a fact, that the cerebral letters are not so much cerebral as they are dental in our speech. If we carefully notice our pronunciation of the letters of the 'ট' class we will see that we articulate 'ট' and 'ড,' for example, almost like English T and D without turning up the tip of the tongue much away from the region of the teeth.

- Masica (1991:102)

- Masica (1991:125)

- Masica (1991:126)

- Masica (1991:116)

- Chatterji (1926:415–416)

- Chatterji (1921:19–20)

- Chatterji (1921:20)

- Hayes & Lahiri (1991:56)

- Hayes & Lahiri (1991:57–58)

- Bhattacharya (2000:6)

- Ferguson & Chowdhury (1960:16–18)

- Khan (2010), pp. 223–224.

Bibliography

- Bhattacharya, Tanmoy (2000), "Bangla (Bengali)" (PDF), in Gary, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.), Encyclopedia of World's Languages: Past and Present (Facts About the World's Languages), New York: WW Wilson, ISBN 978-0-8242-0970-4

- Chatterji, S.K. (1921), "Bengali Phonetics", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 2: 1–25, doi:10.1017/S0041977X0010179X

- Chatterji, S.K. (1926), The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, Calcutta University Press

- Ferguson, C.A.; Chowdhury, M. (1960), "The Phonemes of Bengali: Part 1", Language, 36 (1): 22, doi:10.2307/410622, JSTOR 410622

- Hayes, B.; Lahiri, A. (1991), "Bengali intonational phonology", Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 9: 47, doi:10.1007/BF00133326

- Khan, Sameer ud Dowla (2010), "Bengali (Bangladeshi Standard)" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40 (2): 221–225, doi:10.1017/S0025100310000071

- Masica, C. (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press