English language in Northern England

The English language in Northern England has been shaped by the region's history of settlement and migration, and today encompasses a group of related dialects known as Northern England English (or, simply, Northern English in the United Kingdom). Historically, the strongest influence on the varieties of the English language spoken in Northern England was the Northumbrian dialect of Old English, but contact with Old Norse during the Viking Age and with Irish English following the Great Famine have produced new and distinctive styles of speech. Some "Northern" traits can be found further south than others: only conservative Northumbrian dialects retain the pre-Great Vowel Shift pronunciation of words such as town (/tuːn/, "toon"), but all northern accents lack the FOOT–STRUT split, and this trait extends a significant distance into the Midlands.

There are traditional dialects associated with many of the historic counties, including the Cumbrian dialect, Lancashire dialect, Northumbrian dialect and Yorkshire dialect, but new, distinctive dialects have arisen in cities following urbanisation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: The Manchester urban area has the Manchester dialect, Liverpool and its surrounds have Scouse, Newcastle-upon-Tyne has Geordie and Yorkshire has Tyke. Many Northern English accents are stigmatised, and speakers often attempt to repress Northern speech characteristics in professional environments, although in recent years Northern English speakers have been in demand for call centres, where Northern stereotypes of honesty and straightforwardness are seen as a plus.

Northern English is one of the major groupings of England English dialects; other major groupings include East Anglian English, East and West Midlands English, West Country (Somerset, Dorset, Devon, Cornwall) and Southern English English.

Definition

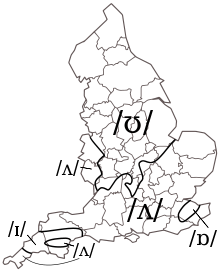

The varieties of English spoken across Great Britain form a dialect continuum, and there is no universally agreed definition of which varieties are Northern.[2] The most restrictive definition of the linguistic North includes only those dialects spoken north of the River Tees. Other linguists, such as John C. Wells, describe these as the dialects of the "Far North" and treat them as a subset of all Northern English dialects. Conversely, Wells uses a very broad definition of the linguistic North, comprising all dialects that have not undergone the TRAP–BATH and FOOT–STRUT splits. Using this definition, the isogloss between North and South runs from the River Severn to the Wash – this definition covers not just the entire North of England (which Wells divides into "Far North" and "Middle North") but also most of the Midlands, including the distinctive Brummie (Birmingham) and Black Country dialects.[3]

In historical linguistics, the dividing line between North and Midlands runs from the River Ribble or River Lune on the west coast to the River Humber on the east coast. The dialects of this region are descended from the Northumbrian dialect of Old English rather than Mercian or other Anglo-Saxon dialects. In a very early study of English dialects, Alexander J Ellis defined the border between the north and the midlands as that where the word house is pronounced with u: to the north (as also in Scots).[4] Although well-suited to historical analysis, this line does not reflect contemporary language; this line divides Lancashire and Yorkshire in half and few would today consider Manchester or Leeds, both located south of the line, as part of the Midlands.[3]

An alternative approach is to define the linguistic North as equivalent to the cultural area of Northern England – approximately the seven historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmorland and Yorkshire, or the three modern statistical regions of North East England, North West England and Yorkshire and the Humber.[5] This approach is taken by the Survey of English Dialects (SED), which uses the historic counties (minus Cheshire) as the basis of study. The SED also groups Manx English with Northern dialects, although this is a distinct variety of English and the Isle of Man is not part of England.[6] Under Wells' scheme, this definition includes Far North and Middle North dialects, but excludes the Midlands dialects.[3]

Scottish English is always considered distinct from Northern England English, although the two have interacted and influenced each other.[7] Both the Scots language and the Northumbrian dialect of English descend from the Old English of Northumbria (diverging in the Middle English period) and are still very similar to each other.[8]

History

Many northern dialects reflect the influence of the Old Norse language strongly, compared with other varieties of English spoken in England.

In addition to previous contact with Vikings, during the 9th and 10th centuries most of northern and eastern England was part of either the Danelaw, or the Danish-controlled Kingdom of Northumbria (with the exception of much of present-day Cumbria, which was part of the Kingdom of Strathclyde). Consequently, Yorkshire dialects, in particular, are considered to have been influenced heavily by Old West Norse and Old East Norse (the ancestor language of modern Norwegian, Swedish and Danish).

However, Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon and Old West Norse (from which modern Norwegian is descended) have arguably had a greater impact, over a longer period, on most northern dialects than Old East Norse. While authoritative quantification is not available, some estimates have suggested as many as 7% of West Cumbrian dialect words are Norse in origin or derived from it.

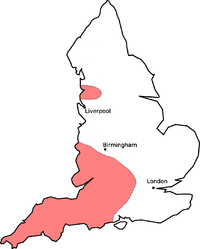

During the mid and late 19th century, there was large-scale migration from Ireland, which affected the speech of parts of Northern England. This is most apparent in the dialects along the west coast, such as Liverpool, Birkenhead, Barrow-in-Furness and Whitehaven. The east-coast town of Middlesbrough also has a significant Irish influence on its dialect, as it grew during the period of mass migration. There was also some influence on speech in Manchester, but relatively little on Yorkshire beyond Middlesbrough.

Varieties

Northern English contains:

- Cheshire dialect

- Cumbrian dialect

- Geordie (spoken in the Newcastle/Tyneside area which includes southern parts of Northumberland)

- Lancashire dialect and accent

- Mackem (spoken in Sunderland/Wearside)

- Mancunian (spoken in Manchester, Salford, various other areas of Greater Manchester, parts of Lancashire and eastern Cheshire).

- Northumbria dialect

- Pitmatic (two variations; one spoken in the former mining communities of County Durham and the other in Northumberland)

- Scouse (spoken in the Liverpool/Merseyside area with variations in west Cheshire and southern Lancashire.)

- Teesside (spoken in Middlesbrough/Stockton-on-Tees, and their surrounding areas.)

- Yorkshire dialect

In some areas, it can be noticed that dialects and phrases can vary greatly within regions too. For example, the Lancashire dialect has many sub-dialects and varies noticeably from West to East and even from town to town. Within as little as 5 miles there can be an identifiable change in accent.

Phonological characteristics

There are several speech features that unite most of the accents of Northern England and distinguish them from Southern England and Scottish accents:[9]

- The accents of Northern England generally do not have the trap–bath split observed in Southern England English, so there is no /ɑː/ in words like bath, ask, etc. Cast is pronounced [kʰast], rather than the [kʰɑːst] pronunciation of most southern accents, and so shares the same vowel as cat [kʰat]. There are a few words in the BATH set like can't, half, calf, master which are pronounced with /ɑː/ in many Northern English accents as opposed to /æ/ in Northern American accents.

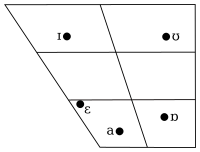

- The /æ/ vowel of cat, trap is normally pronounced [a] rather than the [æ] found in traditional Received Pronunciation or General American while /ɑː/, as in the words palm, cart, start, tomato may not be differentiated from /æ/ by quality, but by length, being pronounced as a longer [aː].

- The foot–strut split is absent in Northern English, so that, for example, cut and put rhyme and are both pronounced with /ʊ/; words like love, up, tough, judge, etc. also use this vowel sound. This has led to Northern England being described "Oop North" /ʊp nɔːθ/ by some in the south of England. Some words with /ʊ/ in RP even have /uː/ – book is pronounced /buːk/ in some Northern accents (particularly in Lancashire, eastern parts of Merseyside where the Lancashire accent is still prevalent and Greater Manchester), while conservative accents also pronounce look as /luːk/.

- The Received Pronunciation phonemes /eɪ/ (as in face) and /əʊ/ (as in goat) are often pronounced as monophthongs (such as [eː] and [oː]), or as older diphthongs (such as /ɪə/ and /ʊə/). However, the quality of these vowels varies considerably across the region, and this is considered a greater indicator of a speaker's social class than the less stigmatised aspects listed above.

- The most common R sound, when pronounced in Northern England, is the typical English

- Lancashire, and Greater Manchester areas north of the city of Manchester may residually be rhotic or pre-consonantally rhotic (pronouncing R before a consonant but not in word-final position), for example, in Accrington and Rochdale.[10]

- Lincolnshire may weakly retain word-final (but not pre-consonantal) rhoticity.[10]

- Uvular rhoticity, in which the same R sound as in French is used, has been described as the traditional "burr" of rural, northern Northumberland—possible as well, though also rare, in County Durham.[10]

- The vowel in dress, test, pet, etc. is slightly more open, transcribed by Wells as /ɛ/ rather than /e/.

- In most areas, the letter y on the end of words as in happy or city is pronounced [ɪ], like the i in bit, and not [i]. This was considered RP until the 1990s. The tenser [i] is found in the far north, and in the Merseyside and Teesside areas.

- The North does not have a clear distinction between the

- Some northern English speakers have noticeable rises in their intonation, even to the extent that, to other speakers of English, they may sound "perpetually surprised or sarcastic."[13]

| English diaphoneme |

Example words | Manchester (Mancunian) |

Lancashire | Yorkshire | Cumbria | Northumberland (Pitmatic) |

Merseyside (Scouse) |

Tyneside (Geordie) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /æ/ | bath, dance, trap | [æ̞~a~ä] | ||||||

| /ɑː/ | bra, calm, father | [aː~äː] |

[ɒː] | |||||

| /ɑːr/ | car, heart, stark | [aː~äː] also, non-rhotic Lancashire: [æː]; rhotic Lancashire: [æːɹ] |

[ɒː] | |||||

| /aɪ/ | fight, ride, try | |||||||

| /aʊ/ | brown, mouth | [aʊ~æʊ] also, Lancashire: [æʊ~ɛʊ] |

[ɐʊ] | [æʊ] | [ɐʊ~u:] | |||

| /eɪ/ | lame, rein, stain | [ɛɪ~e̞ɪ] |

[ɛ̝ː~e̞ː] Lancashire, Cumbria, and Yorkshire, when before /t/: [eɪ~ɛɪ] |

[eɪ] |

[ɪə~e:] | |||

| /ɜːr/ | first, learn, word | [ɜː~ɛː] rhotic Lancashire: [əɹː] |

[ɛ̝ː~e̞ː] |

[øː~ʊː] | ||||

| /ər/ | doctor, martyr, smaller | [ə~ɜ~ɛ] rhotic Lancashire and Northumberland: [əɹ~ɜɹ]; also, Geordie: [ɛ~ɐ] | ||||||

| /iː/ | beam, marine, fleece | [ɪi] | [i] |

[ɪi~i] | ||||

| /i/ | city, honey, parties | [ɪ~e] also, North Yorkshire: [i] |

[ɪi~i] | [i] | ||||

| /ɔː/ | all, bought, saw | [ɒː~ɔː] | ||||||

| /oʊ/ | goal, shown, toe | [ɔʊ~ɔo] | [oː~ɔː] West Yorkshire, more commonly: [ɔː] |

[ɔu~ɜu~ɛʉ] | [ʊə~oː] | |||

| /ʌ/ | bus, flood | [ʊ] Northumberland, less rounded: [ʌ̈]; in Scouse, Manchester, South Yorkshire and (to an extent) Teesside the word one is uniquely pronounced with the vowel [ɒ], and this is also possible for once, among, none, and nothing | ||||||

| /uː/ | food, glue, lose | [ʏː] |

[ʊu] North Yorkshire: [ʉ:] |

[ʉː] |

[yː] | [ʉː] |

[ʉu~ʊu~ɵʊ] | |

| intervocalic & postvocalic /k/ | racquet, joker, luck | [k] or [k~x] | [k] |

[k~x] [k~ç] |

[k~kˀ] | |||

| initial /h/ | hand, head, home | [∅] or [h] | [h] | |||||

| /l/ | lie, mill, salad | [l~ɫ] /l/ is often somewhat "dark" (meaning velarised) [ɫ] |

[l] | |||||

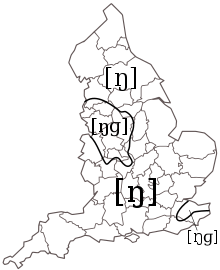

| stressed-syllable /ŋ/ | bang, singer, wrong | [ŋg~ŋ] [ŋ] predominates in the northern half of historical Lancashire |

[ŋ] [ŋg] predominates only in South Yorkshire's Sheffield |

[ŋg~ŋ] | [ŋ] | |||

| post-consonantal & intervocalic /r/ | current, three, pray | [ɹ] or, conservatively, [ɹ~ɾ] [ʁ] in Lindisfarne and traditional, rural, northern Northumberland |

[ɾ] | [ɹ~ɾ] | ||||

| intervocalic, final & pre-consonantal /t/ |

attic, bat, fitness | [ʔ] or [t(ʰ)] | [θ̠] | |||||

Grammar and syntax

The grammatical patterns of Northern England English are similar to those of British English in general. However, there are several unique characteristics that mark out Northern syntax from neighbouring dialects.

Under the Northern subject rule (NSR), the suffix "-s" (which in Standard English grammar only appears in the third person singular present) is attached to verbs in many present and past-tense forms (leading to, for example, "the birds sings"). More generally, third-person singular forms of irregular verbs such as to be may be used with plurals and other grammatical persons; for instance "the lambs is out". In modern dialects, the most obvious manifestation is a levelling of the past tense verb forms was and were. Either form may dominate depending on the region and individual speech patterns (so some Northern speakers may say "I was" and "You was" while others prefer "I were" and "You were") and in many dialects especially in the far North, weren't is treated as the negation of was.[17]

The "epistemic mustn't", where mustn't is used to mark deductions such as "This mustn't be true", is largely restricted within the British Isles to Northern England, although it is more widely accepted in American English, and is likely inherited from Scottish English. A few other Scottish traits are also found in far Northern dialects, such as double modal verbs (might could instead of might be able to), but these are restricted in their distribution and are mostly dying out.[18]

Pronouns

While standard English now only has a single second-person pronoun, you, many Northern dialects have additional pronouns either retained from earlier forms or introduced from other variants of English. The pronouns thou and thee have survived in many rural Northern accents. In some case, these allow the distinction between formality and familiarity to be maintained, while in others thou is a generic second-person singular, and you (or ye) is restricted to the plural. Even when thou has died out, second-person plural pronouns are common. In the more rural dialects and those of the far North, this is typically ye, while in cities and areas of the North West with historical Irish communities, this is more likely to be yous.[19]

Conversely, the process of "pronoun exchange" means that many first-person pronouns can be replaced by the first-person objective plural us (or more rarely we or wor) in standard constructions. These include me (so "give me" becomes "give us"), we (so "we Geordies" becomes "us Geordies") and our (so "our cars" becomes "us cars"). The latter especially is a distinctively Northern trait.[20]

Almost all British vernaculars have regularised reflexive pronouns, but the resulting form of the pronouns varies from region to region. In Yorkshire and the North East, hisself and theirselves are preferred to himself and themselves. Other areas of the North have regularised the pronouns in the opposite direction, with meself used instead of myself. This appears to be a trait inherited from Irish English, and like Irish speakers, many Northern speakers use reflexive pronouns in non-reflexive situations for emphasis. Depending on the region, reflexive pronouns can be pronounced (and often written) as if they ended -sen, -sel or -self (even in plural pronouns) or ignoring the suffix entirely.[19]

Vocabulary

In addition to Standard English terms, the Northern English lexis includes many words derived from Norse languages, as well as words from Middle English that disappeared in other regions. Some of these are now shared with Scottish English and the Scots language, with terms such as bairn ("child"), bonny ("beautiful"), gang or gan ("go/gone/going") and kirk ("church") found on both sides of the Anglo-Scottish border.[21] Very few terms from Brythonic languages have survived, with the exception of place name elements (especially in Cumbrian toponymy) and the Yan Tan Tethera counting system, which largely fell out of use in the nineteenth century. The Yan Tan Tethera system was traditionally used in counting stitches in knitting,[22] as well as in children's nursery rhymes,[22] counting-out games,[22] and was anecdotally connected to shepherding.[22] This was most likely borrowed from a relatively modern form of the Welsh language rather than being a remnant of the Brythonic of what is now Northern England.[22][23]

The forms yan and yen used to mean one as in someyan ("someone") that yan ("that one"), in some northern English dialects, represents a regular development in Northern English in which the Old English long vowel /ɑː/ <ā> was broken into /ie/, /ia/ and so on. This explains the shift to yan and ane from the Old English ān, which is itself derived from the Proto-Germanic *ainaz.[24][25]

A study of a corpus of Late Modern English texts from or set in Northern England found lad ("boy" or "young man") and lass ("girl" or "young woman") were the most widespread "pan-Northern" dialect terms. Other terms in the top ten included a set of three indefinite pronouns owt ("anything"), nowt ("naught" or "nothing") and summat ("something"), the Anglo-Scottish bairn, bonny and gang, and sel/sen ("self") and mun ("must"). Regional dialects within Northern England also had many unique terms, and canny ("clever") and nobbut ("nothing but") were both common in the corpus, despite being limited to the North East and to the North West and Yorkshire respectively.[26]

See also

- Northern subject rule

- Scottish English

- West Germanic languages

Notes

- Upton, Clive; Widdowson, John David Allison (2006). An Atlas of English Dialects. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869274-4.

- Hickey (2015), p. 8–14.

- Wells (1982), pp. 349–351.

- On early English pronunciation : with especial reference to Shakspere and Chaucer, containing an investigation of the correspondence of writing with speech in England from the Anglosaxon period to the present day (1889), Alexander John Ellis, page 19, Line 6

- Hickey (2015), pp. 1–8.

- Wales (2006), pp. 13–14.

- Hickey (2015), p. 2.

- https://www.scotslanguage.com/The_Languages_Our_Neighbours_Speak/Germanic_and_Other_Languages

- Wells (1982), section 4.4.

- Wells (1982), p. 368.

- Beal (2004:130). Note that the source incorrectly transcribes the dark L with the symbol ⟨ɬ⟩, i.e. as if it were the voiceless alveolar lateral fricative.

- Hughes, Arthur, Peter Trudgill, and Dominic James Landon Watt. English Accents & Dialects : an Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of English in the British Isles. 5th ed. London: Hodder Education, 2012. p. 116

- Cruttenden, Alan (March 1981). "Falls and Rises: Meanings and Universals". Journal of Linguistics Vol. 17, No. 1: Cambridge University Press. p. 83. "[T]he rises of Belfast and some northern English cities may sound perpetually surprised or sarcastic to southern Englishmen (the precise attitude imputed will depend on other factors like pitch height and the exact type of rise)".

- Heggarty, Paul; et al., eds. (2013). "Accents of English from Around the World". University of Edinburgh.

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2003). The Phonetics of English and Dutch (PDF) (Fifth Revised ed.). ISBN 9004103406. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-28. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- "English Accents & Dialects". google.com.

- Pietsch (2005), pp. 76–80.

- Beal (2010), pp. 26, 38.

- Hickey (2015), pp. 85–86.

- Hickey (2015), pp. 84–85.

- Trudgill (2002), p. 52.

- Roud, Steve; Simpson, Jacqueline (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press. p. 324. ISBN 0-19-210019-X

- "The Celtic Linguistic Influence". Yorkshire Dialect Society. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Leith, Dick (1997). A Social History of English. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-09797-5. (Alternate ISBN 978-0-415-09797-0)

- Griffiths, Bill (2004). A Dictionary of North East Dialect. Northumbria University Press. p. 191. ISBN 1-904794-16-5.

- Hickey (2015), pp. 144-146.

References

- Beal, Joan (2004). "English dialects in the North of England: phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.). A handbook of varieties of English. 1: Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 113–133. ISBN 3-11-017532-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hickey, Raymond (2015). Researching Northern English. John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-6767-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lodge, Ken (2009). A Critical Introduction to Phonetics. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-8873-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wales, Katie (2006). Northern English: A Social and Cultural History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-48707-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Volume 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52128540-2.

Further reading

- Katie Wales (2006), Northern English: A Social and Cultural History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-86107-1