Hindustani phonology

Hindustani is the lingua franca of northern India and Pakistan, and through its two standardized registers, Hindi and Urdu, a co-official language of India and co-official and national language of Pakistan respectively. Phonological differences between the two standards are minimal.

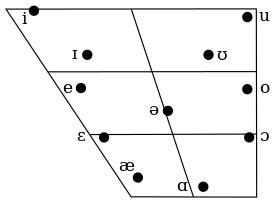

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| long | short | short | long | ||

| Close | iː | ɪ | u | uː | |

| Close mid | eː | oː | |||

| Open mid | ɛː | ə | ɔː | ||

| Open | (æː) | ɑː | |||

Hindustani natively possesses a symmetrical ten-vowel system.[1] The vowels [ə], [ɪ], [ʊ] are always short in length, while the vowels [ɑː], [iː], [uː], [eː], [oː], [ɛː], [ɔː] are always considered long, in addition to an eleventh vowel /æː/ which is found in English loanwords.

Vowel [ə]

Schwa is a short vowel which vanishes to nothing at unstressed position. /ə/ is often realized more open than mid [ə], i.e. as near-open [ɐ].[2]

Vowel [ɑː]

The open back vowel is transcribed in IPA by either [aː] or [ɑː].

Vowels [ɪ], [ʊ], [iː], [uː]

Among the close vowels, what in Sanskrit are thought to have been primarily distinctions of vowel length (that is /i ~ iː/ and /u ~ uː/), have become in Hindustani distinctions of quality, or length accompanied by quality (that is, /ɪ ~ iː/ and /ʊ ~ uː/).[3] The historical opposition of length in the close vowels has been neutralized in word-final position, for example Sanskrit loans śakti (शक्ति – شَکتی 'energy') and vastu (वस्तु – وَستُو 'item') are /ʃəkti/ and /ʋəstu/, not */ʃəktɪ/ and */ʋəstʊ/.[4]

Vowels [ɛ], [ɛː]

The vowel represented graphically as ऐ – اَے (romanized as ai) has been variously transcribed as [ɛː] or [æː].[5] Among sources for this article, Ohala (1999), pictured to the right, uses [ɛː], while Shapiro (2003:258) and Masica (1991:110) use [æː]. Furthermore, an eleventh vowel /æː/ is found in English loanwords, such as /bæːʈ/ ('bat').[6] Hereafter, ऐ – اَے (romanized as ai) will be represented as [ɛː] to distinguish it from /æː/, the latter. Despite this, the Hindustani vowel system is quite similar to that of English, in contrast to the consonants.

| Vowels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Hindi | ISO 15919 | Urdu[7] | Approxi. English

equivalent | ||||

| Initial | Final | Final | Medial | Initial | ||||

| ə[8] | अ | a | ـہ | ـا | ـ◌َـ | اَ | but | |

| aː | आ | ा | ā | ـا | آ | far | ||

| ɪ[9] | इ | ि | i | ـی | ـ◌ِـ | اِ | still | |

| iː[9] | ई | ी | ī | ◌ِـیـ | اِیـ | fee | ||

| u[9] | उ | ु | u | ـو | ـ◌ُـ | اُ | book | |

| uː[9] | ऊ | ू | ū | ◌ُـو | اُو | moon | ||

| eː | ए | े | ē | ے | ـیـ | ایـ | mate | |

| ɛː | ऐ | ै | ai | ◌َـے | ◌َـیـ | اَیـ | hair (Received Pronunciation) | |

| oː | ओ | ो | ō | ـو | او | go (General American) | ||

| ɔː | औ | ौ | au | ◌َـو | اَو | lot (Received Pronunciation) | ||

| ʰ[10] | h | ھ | (Aspirated sounds) cake | |||||

| ◌̃[11] | ँ | m̐ | ں | ـن٘ـ | nasal vowel faun ([ãː, õː], etc.) | |||

| ं | ṁ | jungle | ||||||

In addition, [ɛ] occurs as a conditioned allophone of /ə/ (schwa) in proximity to /ɦ/, if and only if the /ɦ/ is surrounded on both sides by two schwas.[4] and is realised as separate vowel. For example, in kahanā /kəɦ(ə)naː/ (कहना – کَہنا 'to say'), the /ɦ/ is surrounded on both sides by schwa, hence both the schwas will become fronted to short [ɛ], giving the pronunciation [kɛɦɛnaː]. Syncopation of phonemic middle schwa can further occur to give [kɛɦ.naː]. The fronting also occurs in word-final /ɦ/, presumably because a lone consonant carries an unpronounced schwa. Hence, kaha! /kəɦ(ə)/ (कह – کَہہ 'say!') becomes [kɛh] in actual pronunciation. However, the fronting of schwa does not occur in words with a schwa only on one side of the /ɦ/ such as kahānī /kəɦaːniː/ (कहानी – کَہانی 'a story') or bāhar /baːɦər/ (बाहर – باہَر 'outside').

Vowels [ɔ], [ɔː]

The vowel [ɔ] occurs in proximity to /ɦ/ if the /ɦ/ is surrounded by one of the sides by a schwa and on other side by a round vowel. It differs from the vowel [ɔː] in that it is a short vowel. For example, in bahut /bəɦʊt/ the /ɦ/ is surrounded on one side by a schwa and a round vowel on the other side. One or both of the schwas will become [ɔ] giving the pronunciation [bɔɦɔt].

Nasalization of vowels

As in French and Portuguese, there are nasalized vowels in Hindustani. There is disagreement over the issue of the nature of nasalization (barring English-loaned /æ/ which is never nasalized[6]). Masica (1991:117) presents four differing viewpoints:

- there are no *[ẽ] and *[õ], possibly because of the effect of nasalization on vowel quality;

- there is phonemic nasalization of all vowels;

- all vowel nasalization is predictable (i.e. allophonic);

- Nasalized long vowel phonemes (/ɑ̃ː ĩː ũː ẽː ɛ̃ː õː ɔ̃ː/) occur word-finally and before voiceless stops; instances of nasalized short vowels ([ə̃ ɪ̃ ʊ̃]) and of nasalized long vowels before voiced stops (the latter, presumably because of a deleted nasal consonant) are allophonic.

Masica[12] supports this last view.

Consonants

Hindustani has a core set of 28 consonants inherited from earlier Indo-Aryan. Supplementing these are two consonants that are internal developments in specific word-medial contexts,[14] and seven consonants originally found in loan words, whose expression is dependent on factors such as status (class, education, etc.) and cultural register (Modern Standard Hindi vs Urdu).

Most native consonants may occur geminate (doubled in length; exceptions are /bʱ, ɽ, ɽʱ, ɦ/). Geminate consonants are always medial and preceded by one of the interior vowels (that is, /ə/, /ɪ/, or /ʊ/). They all occur monomorphemically except [ʃː], which occurs only in a few Sanskrit loans where a morpheme boundary could be posited in between, e.g. /nɪʃ + ʃiːl/ for niśśīl [nɪʃʃiːl] ('without shame').[6]

For the English speaker, a notable feature of the Hindustani consonants is that there is a four-way distinction of phonation among plosives, rather than the two-way distinction found in English. The phonations are:

- tenuis, as /p/, which is like ⟨p⟩ in English spin

- voiced, as /b/, which is like ⟨b⟩ in English bin

- aspirated, as /pʰ/, which is like ⟨p⟩ in English pin, and

- murmured, as /bʱ/.

The last is commonly called "voiced aspirate", though Shapiro (2003:260) notes that,

"Evidence from experimental phonetics, however, has demonstrated that the two types of sounds involve two distinct types of voicing and release mechanisms. The series of so-called voice aspirates should now properly be considered to involve the voicing mechanism of murmur, in which the air flow passes through an aperture between the arytenoid cartilages, as opposed to passing between the ligamental vocal bands."

The murmured consonants are believed to be a reflex of murmured consonants in Proto-Indo-European, a phonation that is absent in all branches of the Indo-European family except Indo-Aryan and Armenian.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɳ) (ɽ̃) | (ɲ) | (ŋ) | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t̪ | ʈ | tʃ | k | (q) | |

| voiceless aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | b | d̪ | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | |||

| voiced aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | |||

| Flap and trill | plain | r | ɽ | |||||

| voiced aspirated | ɽʱ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | (x) | ɦ | ||

| voiced | ʋ | z | (ʒ) | (ɣ) | ||||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||||

- Notes

- Marginal and non-universal phonemes are in parentheses.

- /ɽ/ is lateral [ɺ̢] for some speakers.[15]

- /ɣ/ is post-velar.[16]

Stops in final position are not released. /ʋ/ varies freely with [v], and can also be pronounced [w]. /r/ is essentially a trill.[17] In intervocalic position, it may have a single contact and be described as a flap [ɾ],[18] but it may also be a clear trill, especially in word-initial and syllable-final positions, and geminate /rː/ is always a trill in Arabic and Persian loanwords, e.g. zarā [zəɾaː] (ज़रा – ذرا 'little') versus well-trilled zarrā [zərːaː] (ज़र्रा – ذرّہ 'particle').[2] The palatal and velar nasals [ɲ, ŋ] occur only in consonant clusters, where each nasal is followed by a homorganic stop, as an allophone of a nasal vowel followed by a stop, and in Sanskrit loanwords.[14][2] There are murmured sonorants, [lʱ, rʱ, mʱ, nʱ], but these are considered to be consonant clusters with /ɦ/ in the analysis adopted by Ohala (1999).

The fricative /ɦ/ in Hindustani is typically voiced (as [ɦ]), especially when surrounded by vowels, but there is no phonemic difference between this voiced fricative and its voiceless counterpart [h] (Hindustani's ancestor Sanskrit has such a phonemic distinction).

Hindustani also has a phonemic difference between the dental plosives and the so-called retroflex plosives. The dental plosives in Hindustani are laminal-denti alveolar as in Spanish, and the tongue-tip must be well in contact with the back of the upper front teeth. The retroflex series is not purely retroflex; it actually has an apico-postalveolar (also described as apico-pre-palatal) articulation, and sometimes in words such as ṭūṭā /ʈuːʈaː/ (टूटा – ٹُوٹا 'broken') it even becomes alveolar.[19]

In some Indo-Aryan languages, the plosives [ɖ, ɖʱ] and the flaps [ɽ, ɽʱ] are allophones in complementary distribution, with the former occurring in initial, geminate and postnasal positions and the latter occurring in intervocalic and final positions. However, in Standard Hindi they contrast in similar positions, as in nīṛaj (नीड़ज – نیڑج 'bird') vs niḍar (निडर – نڈر 'fearless').[20]

Allophony of [v] and [w]

[v] and [w] are allophones in Hindustani. These are distinct phonemes in English, but both are allophones of the phoneme /ʋ/ in Hindustani (written ⟨व⟩ in Hindi or ⟨و⟩ in Urdu), including loanwords of Arabic and Persian origin. More specifically, they are conditional allophones, i.e. rules apply on whether ⟨व⟩ is pronounced as [v] or [w] depending on context. Native Hindi speakers pronounce ⟨व⟩ as [v] in vrat (व्रत – ورت, 'vow') and [w] in pakwān (पकवान – پکوان 'food dish'), treating them as a single phoneme and without being aware of the allophonic distinctions, though these are apparent to native English speakers. The rule is that the consonant is pronounced as semivowel [w] in onglide position, i.e. between an onset consonant and a following vowel.[21]

However, the allophone phenomenon becomes obvious when speakers switch languages. When speakers of other languages that have a distinction between [v] and [w] speak Hindustani, they might pronounce ⟨व و⟩ in vrat (व्रत – ورت) as [w], i.e. as [wrət] instead of the correct [vrət]. This results in an intelligibility problem because [wrət] can easily be confused for aurat (औरत عورت) [ˈɔːɾət], which means "woman" instead of "vow" in Hindustani. Similarly, Hindustani speakers might unconsciously apply their native allophony rules to English words, pronouncing war /wɔːɹ/ as [vɔːɹ] or advance /ədˈvɑːns/ as [ədˈwɑːns], which can result in intelligibility problems with native English speakers.[21]

In some situations, the allophony is non-conditional, i.e. the speaker can choose [v], [w] or an intermediate sound based on personal habit and preference, and still be perfectly intelligible, as long as the meaning is constant. This includes words such as advait (अद्वैत – ادویت) which can be pronounced equally correctly as [ədˈwɛːt] or [ədˈvɛːt].[21]

External borrowing

Loanwords from Sanskrit reintroduced /ɳ/ into formal Modern Standard Hindi. In casual speech it is usually replaced by /n/.[6] It does not occur initially and has a nasalized flap [ɽ̃] as a common allophone.[14]

Loanwords from Persian (including some words which Persian itself borrowed from Arabic or Turkish) introduced six consonants, /f, z, ʒ, q, x, ɣ/. Being Persian in origin, these are seen as a defining feature of Urdu, although these sounds officially exist in Hindi and modified Devanagari characters are available to represent them.[22][23] Among these, /f, z/, also found in English and Portuguese loanwords, are now considered well-established in Hindi; indeed, /f/ appears to be encroaching upon and replacing /pʰ/ even in native (non-Persian, non-English, non-Portuguese) Hindi words as well as many other Indian languages such as Bengali, Gujarati and Marathi, as happened in Greek with phi.[14] This /pʰ/ to /f/ shift also occasionally occurs in Urdu.[24] While [z] is a foreign sound, it is also natively found as an allophone of /s/ beside voiced consonants.

The other three Persian loans, /q, x, ɣ/, are still considered to fall under the domain of Urdu, and are also used by many Hindi speakers; however, some Hindi speakers assimilate these sounds to /k, kʰ, ɡ/ respectively.[22][25] The sibilant /ʃ/ is found in loanwords from all sources (English, Portuguese, Persian, Sanskrit) and is well-established.[6] The failure to maintain /f, z, ʃ/ by some Hindi speakers (often non-urban speakers who confuse them with /pʰ, dʒ, s/) is considered nonstandard.[22] Yet these same speakers, having a Sanskritic education, may hyperformally uphold /ɳ/ and [ʂ]. In contrast, for native speakers of Urdu, the maintenance of /f, z, ʃ/ is not commensurate with education and sophistication, but is characteristic of all social levels.[25] The sibliant /ʒ/ is very rare and is found in loanwords from Persian, Portuguese, and English and is considered to fall under the domain of Urdu and although it is officially present in Hindi, many speakers of Hindi assimilate it to /z/ or /dʒ/.

Being the main sources from which Hindustani draws its higher, learned terms– English, Sanskrit, Arabic, and to a lesser extent Persian provide loanwords with a rich array of consonant clusters. The introduction of these clusters into the language contravenes a historical tendency within its native core vocabulary to eliminate clusters through processes such as cluster reduction and epenthesis.[26] Schmidt (2003:293) lists distinctively Sanskrit/Hindi biconsonantal clusters of initial /kr, kʃ, st, sʋ, ʃr, sn, nj/ and final /tʋ, ʃʋ, nj, lj, rʋ, dʒj, rj/, and distinctively Perso-Arabic/Urdu biconsonantal clusters of final /ft, rf, mt, mr, ms, kl, tl, bl, sl, tm, lm, ɦm, ɦr/.

Suprasegmental features

Hindustani has a stress accent, but it is not as important as in English. To predict stress placement, the concept of syllable weight is needed:

- A light syllable (one mora) ends in a short vowel /ə, ɪ, ʊ/: V

- A heavy syllable (two moras) ends in a long vowel /aː, iː, uː, eː, ɛː, oː, ɔː/ or in a short vowel and a consonant: VV, VC

- An extra-heavy syllable (three moras) ends in a long vowel and a consonant, or a short vowel and two consonants: VVC, VCC

Stress is on the heaviest syllable of the word, and in the event of a tie, on the last such syllable. If all syllables are light, the penultimate is stressed. However, the final mora of the word is ignored when making this assignment (Hussein 1997) [or, equivalently, the final syllable is stressed either if it is extra-heavy, and there is no other extra-heavy syllable in the word or if it is heavy, and there is no other heavy or extra-heavy syllable in the word]. For example, with the ignored mora in parentheses:[27]

- kaː.ˈriː.ɡə.ri(ː)

- ˈtʃəp.kə.lɪ(ʃ)

- ˈʃoːx.dʒə.baː.ni(ː)

- ˈreːz.ɡaː.ri(ː)

- sə.ˈmɪ.t(ɪ)

- ˈqɪs.mə(t)

- ˈbaː.ɦə(r)

- roː.ˈzaː.na(ː)

- rʊ.ˈkaː.ja(ː)

- ˈroːz.ɡaː(r)

- aːs.ˈmaːn.dʒaː(h) ~ ˈaːs.mãː.dʒaː(h)

- kɪ.ˈdʱə(r)

- rʊ.pɪ.ˈa(ː)

- dʒə.ˈnaː(b)

- əs.ˈbaː(b)

- mʊ.səl.ˈmaː(n)

- ɪɴ.qɪ.ˈlaː(b)

- pər.ʋər.dɪ.ˈɡaː(r)

Content words in Hindustani normally begin on a low pitch, followed by a rise in pitch.[28][29] Strictly speaking, Hindustani, like most other Indian languages, is rather a syllable-timed language. The schwa /ə/ has a strong tendency to vanish into nothing (syncopated) if its syllable is unaccented.

See also

- IPA vowel chart with audio

- IPA pulmonic consonant chart with audio

- IPA chart (vowels and consonants) - 2015. (pdf file)

- Schwa deletion in Indo-Aryan languages

References

- Masica (1991:110)

- Ohala (1999:102)

- Masica (1991:111)

- Shapiro (2003:258)

- Masica (1991:114)

- Ohala (1999:101)

- Diacritics in Urdu are normally not written and usually implied and interpreted based on the context of the sentence

- [ɛ] occurs as a conditioned allophone of /ə/ near an /ɦ/ surrounded on both sides by schwas. Usually, the second schwa undergoes syncopation, and the resultant is just an [ɛ] preceding an /ɦ/. Hindi does not have a letter to represent ə as it is usually implied

- /iː, ɪ/ and /uː, ʊ/ are neutralised to [i, u] at the end of a word.

- Hindi has individual letters for aspirated consonants whereas Urdu has a specific letter to represent an aspirated consonant

- No words in Hindustani can begin with a nasalised letter/diacritic. In Urdu the media form (letter) for representing a nasalised word is: ن٘ (nūn + small nūn ghunna diacritic)

- Masica (1991:117–118)

- Derived: Phonetics from UCLA.edu but re-recorded.

- Shapiro (2003:260)

- Masica (1991:98)

- Kachru (2006:20)

- Nazir Hassan (1980) Urdu phonetic reader, Omkar Nath Koul (1994) Hindi Phonetic Reader, Indian Institute of Language Studies; Foreign Service Institute (1957) Hindi: Basic Course

- "r is a tip dental trill, and often has but one flap", Thomas Cummings (1915) An Urdu Manual of the Phonetic, Inductive Or Direct Method

- Tiwari, Bholanath ([1966] 2004) हिन्दी भाषा (Hindī Bhāshā), Kitāb Mahal, Allahabad, ISBN 81-225-0017-X.

- Masica (1991:97)

- Janet Pierrehumbert, Rami Nair (1996), Implications of Hindi Prosodic Structure (Current Trends in Phonology: Models and Methods), European Studies Research Institute, University of Salford Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1-901471-02-1,

... showed extremely regular patterns. As is not uncommon in a study of subphonemic detail, the objective data patterned much more cleanly than intuitive judgments ... [w] occurs when /व و/ is in onglide position ... [v] occurs otherwise ...

- A Primer of Modern Standard Hindi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1989. ISBN 9788120805088. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- "Hindi Urdu Machine Transliteration using Finite-state Transducers" (PDF). Association for Computational Linguistics. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781135797119 – via Google Books.

- Masica (1991:92)

- Shapiro (2003:261)

- Hayes (1995:276)

- http://www.und.nodak.edu/dept/linguistics/theses/2001Dyrud.PDF Dyrud, Lars O. (2001) Hindi-Urdu: Stress Accent or Non-Stress Accent? (University of North Dakota, master's thesis)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Ramana Rao, G.V. and Srichand, J. (1996) Word Boundary Detection Using Pitch Variations. (IIT Madras, Dept. of Computer Science and Engineering)

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hindi pronunciation. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urdu pronunciation. |

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Hayes, Bruce (1995), Metrical stress theory, University of Chicago Press.

- Hussein, Sarmad (1997), Phonetic Correlates of Lexical Stress in Urdu, Northwestern University.

- Kachru, Yamuna (2006), Hindi, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-3812-X.

- Ohala, Manjari (1999), "Hindi", in International Phonetic Association (ed.), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: a Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge University Press, pp. 100–103, ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila (2003), "Urdu", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 286–350, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Shapiro, Michael C. (2003), "Hindi", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 250–285, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.