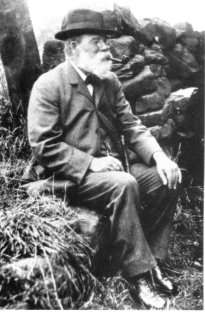

Joseph Wright (linguist)

Joseph Wright FBA (31 October 1855 – 27 February 1930)[1] was an English philologist who rose from humble origins to become Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford University.

Joseph Wright | |

|---|---|

Joseph Wright | |

| Born | 31 October 1855 |

| Died | 27 February 1930 (aged 74) |

| Academic work | |

| Main interests | Germanic languages English dialects |

| Notable works | English Dialect Dictionary |

| Influenced | J. R. R. Tolkien |

Early life

Wright was born in Idle, near Bradford in Yorkshire, the second son of Dufton Wright, a woollen cloth weaver and quarryman, and his wife Sarah Ann (née Atkinson).[1] He started work as a "donkey-boy" in a quarry around 1862 at the age of 6 years old, leading a donkey-drawn cart full of tools to the smithy to be sharpened. He later became a bobbin doffer – responsible for removing and replacing full bobbins – in a Yorkshire mill in Sir Titus Salt's model village. Although he learnt his letters and numbers at the Salt's Factory School, he was unable to read a newspaper until he was 15. He later said of this time: "Reading and writing, for me, were as remote as any of the sciences."[2]

By now a wool-sorter earning £1 a week, after around 1870, Wright became increasingly fascinated with languages and began attending night-school to learn French, German and Latin, as well as maths and shorthand. At the age of 18, around 1874, he even started his own night-school, charging his colleagues twopence a week.[3]

By 1876, Wright had saved £40 and could afford a term's study at the University of Heidelberg, although he walked from Antwerp, a distance of over 400 km, to save money.

Returning to Yorkshire, Wright continued his studies at the Yorkshire College of Science (later the University of Leeds) while working as a schoolmaster. A former pupil of Wright's recalled: "With a piece of chalk [he would] draw illustrative diagrams at the same time with each hand, and talk while he was doing it."[3]

Wright later returned to Heidelberg, and in 1885, completed his PhD on Qualitative and Quantitative Changes of the Indo-Germanic Vowel System in Greek[2] under Hermann Osthoff, later founding the field of scientific study called "English dialectology".

Career

In 1888, after his return from Germany, Wright was offered a post at Oxford University by Professor Max Müller, and became a lecturer to the Association for the Higher Education of Women and deputy lecturer in German at the Taylor Institution.[3]

From 1891 to 1901, Wright was Deputy Professor and from 1901 to 1925 Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford.

Wright specialised in the Germanic languages and wrote a range of introductory grammars for Old English, Middle English, Old High German, Middle High German and Gothic which were still being revised and reprinted 50 years after his death. He also wrote a historical grammar of German.

Wright had a strong interest in English dialects and claimed that his 1892 book A Grammar of the Dialect of Windhill[4] was "the first grammar of its kind in England".

Wright's greatest achievement is considered to be the editing of the six-volume English Dialect Dictionary, which he published between 1898 and 1905, initially at his own expense. This remains a definitive work, a snapshot of English dialect speech at the end of the 19th century. In the course of his work on the Dictionary, he formed a committee to gather Yorkshire material, which gave rise in 1897 to the Yorkshire Dialect Society, which claims to be the world's oldest surviving dialect society. Wright had been offered a position at a Canadian university, who would have paid him an annual salary of £500 – a very generous salary at the time. However, Wright opted to stay in Oxford and finish the Dialect Dictionary without any financial backing from a sponsor.

In 1925, Wright was the inaugural recipient of the British Academy's Biennial Prize for English Literature (now the Sir Israel Gollancz Prize), awarded for publications in Early English Language and Literature.[5]

Wright's papers are in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford in Oxford, England, United Kingdom, Europe.

Personal life

In 1896 he married Elizabeth Mary Lea (1863–1958), with whom he co-authored his Old and Middle English Grammars. She also wrote the book, Rustic Speech and Folklore (Oxford University Press 1913), in which she makes reference to their various walking and cycle trips into the Yorkshire Dales, as well as various articles and essays.

The couple had two children – Willie Boy and Mary – both of whom died in childhood.[2]

Wright and his wife were known for their hospitality to their students and would often invite a dozen or more, both men and women, to their home for Yorkshire Sunday teas. On these occasions Wright would perform his party trick of making his Aberdeen Terrier, Jack, lick his lips when Wright said the Gothic words for fig-tree – smakka bagms.[6]

Although Wright was a progressive to the extent that he believed women were entitled to a university education, he did not believe that women should be made voting members of the university, saying they were, "... less independent in judgement than men and apt to run in a body like sheep".[3]

Although his energies were for the most part directed towards his work, Wright also enjoyed gardening and followed Yorkshire cricket and football teams.[2]

At the age of seventy-four he succumbed to pneumonia, and died at his Oxford home, Thackley, 119 Banbury Road, on 27 February 1930, and was buried at Oxford.[7] His last word was "Dictionary".[2] In 1932 his widow, Elizabeth, published a biography of Wright, The Life of Joseph Wright.[8]

Legacy

Wright was an important early influence on J. R. R. Tolkien, and was one of his tutors at Oxford: studying the Grammar of the Gothic Language (1910) with Wright seems to have been a turning point in Tolkien's life.[9] Writing to his son Michael in 1963, J. R. R. Tolkien reflected on his time studying with Wright:

"Years before I had rejected as disgusting cynicism by an old vulgarian the words of warning given me by old Joseph Wright. ‘What do you take Oxford for, lad?’ ‘A university, a place of learning.’ ‘Nay, lad, it‘s a factory! And what’s it making? I‘ll tell you. It‘s making fees. Get that in your head, and you‘ll begin to understand what goes on.‘ Alas! by 1935 I now knew that it was perfectly true. At any rate as a key to dons‘ behaviour."[10]

In the course of editing the Dictionary (1898), Wright corresponded regularly with Thomas Hardy about the Dorset dialect.[11][12]

Wright was greatly admired by Virginia Woolf, who writes of him in her diary:

"The triumph of learning is that it leaves something done solidly for ever. Everybody knows now about dialect, owing to his dixery."[13]

Wright was Woolf's inspiration for the character of "Mr Brook" in The Pargiters (n.d.), an early draft of The Years (1937).[14]

In popular culture

In the 2019 biopic Tolkien, Professor Wright is portrayed by Sir Derek Jacobi.

Notes

- Kellett, Arnold (2004). "Joseph Wright". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Lunnon, Jenny (28 February 2008). "From woollen mills to dreaming spires". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "Idle scholar who brought local language to book". Oxford Today. 22. 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- A Grammar of the Dialect of Windhill in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Illustrated by a series of dialect specimens, phonetically rendered; with a glossarial index of the words used in the grammar and specimens. London: Kegan Paul, 1892

- "Sir Israel Gollancz Prize". British Academy. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Carpenter 1977, p. 64.

- "Wright, Joseph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Wright 1932.

- Carpenter 1977, pp. 63–64.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1981). Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien. London: Allen & Unwin. Originally published 1 November 1963.

- Chapman 1990, p. 33.

- Firth 2014.

- Fowler, Rowena (2002). "Virginia Woolf: Lexicographer" (PDF). English Language Notes. xxix. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Snaith 2000, p. 109.

References

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). Tolkien: A Biography. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-04-928037-6.

- Chapman, Raymond (1990). The Language of Thomas Hardy. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780312036652.

- Firth, Lisa (2014). "The tale of Joseph Wright: from donkey boy to don". The Local Leader. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Holder, R. W. (2005). The Dictionary Men. Their lives and times. Bath University Press. ISBN 0-86197-129-9.

- Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198607663. (extract)

- Snaith, Anna (2000). Virginia Woolf: Public and Private Negotiations. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 9781403911780.

- Wright, Elizabeth Mary (1932). The Life of Joseph Wright. Oxford: Oxford University Press. vol. 1, vol. 2

External links

- Works by Joseph Wright at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Wright at Internet Archive

- Wright's Old High German Primer

- Wright's Middle High German Primer

- Wright's Grammar of the Gothic Language

- Joseph Wright, Comparative Grammar Of The Greek Language