Western American English

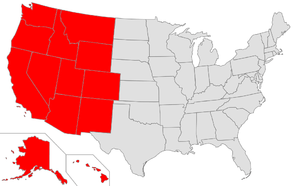

Western American English (also known as Western U.S. English) is a variety of American English that largely unites the entire western half of the United States as a single dialect region, including the states of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. It also generally encompasses Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, some of whose speakers are classified additionally under Pacific Northwest English.

| Western American English | |

|---|---|

| Region | Western United States |

Indo-European

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

States where Western American English and its dialects are spoken | |

The West was the last area in the United States to be reached during the gradual westward expansion of English-speaking settlement and its history shows considerable mixing and leveling of the linguistic patterns of other regions. As the settlement populations are relatively young when compared with other regions, the American West is a dialect region in formation.[1] According to the 2006 Atlas of North American English, as a very broad generalization, Western U.S. accents are differentiated from Southern U.S. accents in maintaining /aɪ/ as a diphthong, from Northern U.S. accents by fronting /u/ (the GOOSE vowel), and from both by most consistently showing the cot–caught merger.[2]

Phonology and phonetics

The Western dialect of American English is somewhat variable and not necessarily distinct from "General American." Western American English is characterized primarily by two phonological features: the cot-caught merger (as distinct from most Northern and Southern U.S. English) and the fronting of /u/ but not /oʊ/ (as distinct from most Southern and Mid-Atlantic American English, in which both of those vowels are fronted, as well as from most Northern U.S. English, in which both of these remain backed).[3]

Like most Canadian dialects and younger General American, /ɑ/ allophones remain back and may be either rounded or unrounded due to a merger between /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ (commonly represented in younger General American, respectively, so that words like cot and caught, or pod and pawed, are perfect homophones (except in San Francisco).[3] Unlike in Canada, however, the occurrence of Canadian raising of the /aʊ/ and /aɪ/ diphthongs is not as consistent and pronounced.[4] A significant minority of Western speakers have the pin–pen merger or a closeness to the merger, especially around Bakersfield, California, though it is a sound typically associated with Southern U.S. dialect, which influenced the area.[5] The West is entirely rhotic and the Mary–marry–merry merger is complete (as in most of North America), so that words like Mary, marry, and merry are all pronounced identically because of the merger of all three of those vowels' sounds when before r (towards [ɛ]). T-glottalization is more common in Western dialects than other varieties of American English, particularly among younger speakers.[6]

Vocabulary

- baby buggy as opposed to baby carriage (more common east of the Mississippi River, mixed in the region between the Mississippi and Appalachian Mountains, rare east of the Appalachians)[7]

- bear claw: a large stuffy pastry[8]

- buckaroo: cowboy

- Originating in California, buckaroo is an Anglicization of the Mexican Spanish translation of cowboy vaquero; the corresponding term which originated in Texas is "wrangler" or "horse wrangler", itself an Anglicization of the Mexican caballerango.[9]

- firefly: preferred term for any insect of the Lampyridae family[10]

- frontage road: a service or access road[10]

- gunnysack as opposed to burlap bag (the latter more common east of the Mississippi)[7]

- hella: very (adverb); much or many (adjective); originated in the San Francisco Bay Area and now used throughout Northern California

- mud hen: the American coot[7]

- shivaree as opposed to belling or serenade

- Shivaree is the more common usage east of the Mississippi and in Kentucky and Tennessee; "belling" is the more common usage in Ohio, while "serenade" is the more common usage in Atlantic states—except New York and Connecticut—and the Appalachians)[7]

- tennis shoes: preferred term for general athletic shoes, with sneakers being the second-most common term[10]

Sub-varieties

Several sub-types of the Western dialect exist or appear to be currently in formation. A trend evident particularly in some speakers from the Salt Lake City, Utah and Flagstaff, Arizona areas, as well as in some Californian and New Mexican English, is the completion of, or transition towards, a full–fool merger.[11]

California

A noticeable California Vowel Shift has been observed in the English of some California speakers scattered throughout the state,[12] though especially younger and coastal speakers. This shift involves two elements, including that the vowel in words like toe, rose, and go (though remaining back vowels elsewhere in the Western dialect), and the vowel in words like spoon, move, and rude are both pronounced farther forward in the mouth than most other English dialects; at the same time, a lowering chain movement of the front vowels is occurring (identical to the Canadian Vowel Shift), so that, to listeners of other English dialects, sit may approach the sound of set, set may approach sat, and sat may approach sot. This front-vowel lowering is also reported around Portland, Oregon, the hub of a unique Northwestern variety of American English that demonstrates other similarities with Canadian English.[13] Some older, Irish-American residents spoke what was called the Mission brogue, a dialect of English far more similar to New York English.

Utah

Utah is the only U.S. state with a majority population belonging to a single religious denomination, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the cause of certain cultural influences on the state,[14] including some dialect distinctions; however, even these characteristics exist only among a minority of Utahns.[15] Members of the LDS Church may use the propredicate "do" or "done", as in the sentence "I would have done",[16] unlike other Americans. Some Utahns tense front vowels before /l/, which results in pronouncing "milk" as [mɛlk].[17] One prominent older, declining feature of Utah English is the cord-card merger without a horse-hoarse merger, particularly along the Wasatch Front, which merges /ɑɹ/ (as in far) and /ɔɹ/ (as in for), while keeping /oʊɹ/ distinct (as in four).[18][19]

Hawaiʻi

Studies demonstrate that gender, age, and ability to speak Hawaiian Creole (a language locally called "Pidgin" and spoken by about two-fifths of Hawaii residents) correlate with the recent emergence of different Hawaiian English accents. In a 2013 study of twenty Oʻahu-raised native English speakers, those who do not speak Pidgin or are male were shown to lower /ɪ/ and /ɛ/; younger speakers of the first group also lowered /æ/, and younger participants in general backed /æ/.[20] Though this movement of these vowels is superficially similar to the California Vowel Shift, it is not believed to be due to a chain shift, though Hawaii residents do have a cot–caught merger, at least among younger speakers.[20] Unlike most Americans, Hawaii residents may not demonstrate any form of /æ/ tensing (even before nasal consonants, as with most Western Americans).[21]

Alaska

Currently, there is not enough data on the English of Alaska to either include it within Western American English or assign it its own "separate status".[22] Of two documented speakers in Anchorage, their cot-caught merger is completed or transitional, /aʊ/ is not fronted, /oʊ/ is centralized, the placement of /u/ is inconsistent, and ag approaches the sound of egg.[23] Not far from Anchorage, in Alaska's Matanuska-Susitna Valley, is an entirely separate accent: a Minnesota-like one in a dialect enclave of North-Central American English, due to immigration of Minnesotans to the valley in the 1930s.[24]

See also

- Boontling

- African-American English

- California English

- English in New Mexico

- Hawaiian Pidgin

- Pacific Northwest English

- Utah English

- San Francisco English

- Inland California English

- American Indian English

References

- Busby, M. (2004). The Southwest. The Greenwood encyclopedia of American regional cultures. Greenwood Press. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-0-313-32805-3. Retrieved August 29, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:146)

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:279)

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:135)

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:68)

- Eddington, David; Taylor, Michael (August 1, 2009). "T-Glottalization IN AMERICAN ENGLISH". American Speech. 84 (3): 298–314. doi:10.1215/00031283-2009-023. ISSN 0003-1283.

- Craig M. Carver, American Regional Dialects: A Word Geography (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1987), pp. 206f

- "Bear claw". Dictionary of American Regional English. Retrieved 2017. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Carver, American Regional Dialects, p. 223

- Vaux, Bert and Scott Golder. 2003. The Harvard Dialect Survey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Linguistics Department.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:70, 285–6)

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:78, 80, 82, 105, 158)

- Ward, Michael (2003). Portland Dialect Study: The Fronting of /ow, u, uw/ in Portland, Oregon (PDF). Portland State University.

- Canham, Matt (April 17, 2012). "Census: Share of Utah's Mormon residents holds steady". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014.

- Lillie, Diane (April 1, 1997). "Utah English". Deseret Language and Linguistic Society Symposium. 23 (1): 54.

- Di Paolo, Marianna (1993). "Propredicate Do in the English of the Intermountain West". American Speech. 68 (4): 339–356. doi:10.2307/455771. ISSN 0003-1283. JSTOR 455771.

- Lillie, Diane Deford. The Utah Dialect Survey. 1998. Brigham Young University, Master’s thesis.

- Reeves, Larkin (August 6, 2009). "Patterns of Vowel Production in Speakers of American English from the State of Utah". All Theses and Dissertations.

- Bowie, David (February 1, 2008). "ACOUSTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF UTAH'S CARD-CORD MERGER". American Speech. 83 (1): 35–61. doi:10.1215/00031283-2008-002. ISSN 0003-1283.

- Drager, Katie, M. Joelle Kirtley, James Grama, Sean Simpson (2013). "Language variation and change in Hawai‘i English: KIT, DRESS, and TRAP". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 19: Iss. 2, Article 6: 42, 48-49.

- Kirtley, M., Grama, J., Drager, K., & Simpson, S. (2016). "An acoustic analysis of the vowels of Hawai‘i English". Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 46(1), 79-97. doi:10.1017/S0025100315000456

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:141)

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:104, 141, 159, 182)

- Sheidlower, Jesse (2008). "What Kind of Accent Does Sarah Palin Have?" Slate. The Slate Group, LLC.

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006), The Atlas of North American English, Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter, pp. 187–208, ISBN 978-3-11-016746-7